One balmy night on the isle of Kauai, Jerry Jeff Walker, the modern cowboy singer, came out of a bar and couldn’t get into his rent-a-car, so he started banging away at it with a heavy wooden chair. Then an outraged Kauaian appeared. Jerry Jeff had the wrong car.

How do you explain to somebody why you are heatedly attacking his automobile with a chair? How, indeed, does anyone explain anything Jerry Jeff does? I have been with him in Phoenix, in Tucson, in New York City, in his house outside Austin, in Hill Country rain, and in several bars, motel rooms, stupors, performance halls, quandaries, vehicles, and middles of the night. And even onstage. And I have lived to tell the story.

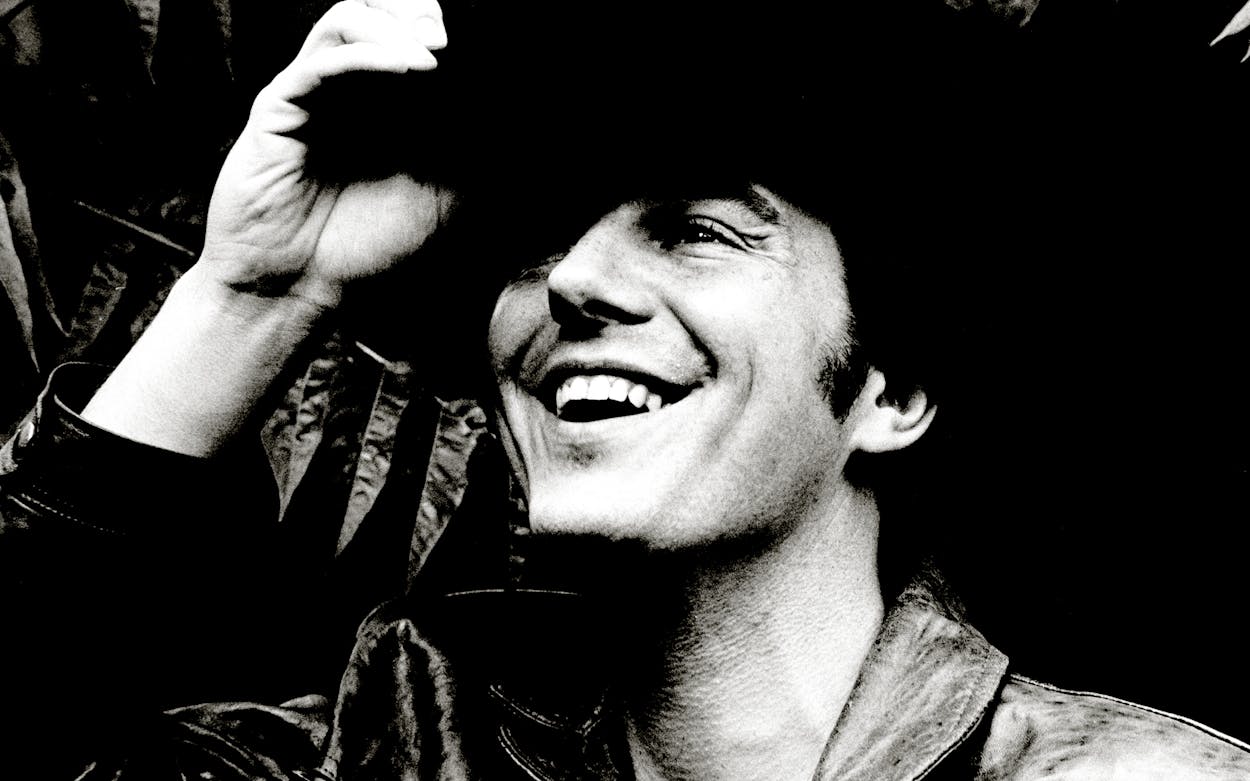

And the story is: Jerry Jeff feels most like himself when, in his words, he is “unconscious onstage.”

Who is Jerry Jeff that we should be so mindful of his unconscious? He may come from upstate New York, but he reached Texas—both Austin and Luckenbach—before Willie Nelson did, and he has stayed on. He is not the meticulous artist Willie is, but Jerry Jeff’s are the grabbiest versions of several songs without which Texas would be poorer and quieter: Guy Clark’s “L.A. Freeway,” Ray Wylie Hubbard’s “Up Against the Wall, Redneck,” Gary P. Nunn’s “London Homesick Blues,” his own “Hill Country Rain.” If anybody is a pioneer and exemplar of the Austin sound, it is Jerry Jeff.

The folk-rock-country-desperado image he presents has been too elusive to gain him superstardom, but his albums sell steadily around the country. There runs through all of his varied numbers a progressively less lilting but consistently engaging and unmistakable voice. Furthermore, he has established a truly distinguished standard of modern musical-cowboy misbehavior.

Not long ago Jerry Jeff telephoned my home in Massachusetts to report that he would be appearing in nearby Hartford the next weekend. My wife and I were out; our friend Rose took the message. “Where exactly in Hartford are you going to be?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” said Jerry Jeff. “Where exactly am I now?”

Since there are no telephones in drunk tanks or on the ground beneath motorcycle boots, Jerry Jeff was presumably in neither of those places. Nor was he likely to be in the White House. Last year he showed up there at Jimmy Carter’s invitation, but after cooling his heels for two hours (some presidential crisis graver than Jerry Jeff’s presence having arisen) he walked out, saying, “I guess the President and I aren’t going to get together, because I’m not hanging around this place any longer and I hear he don’t hang out in any bars.”

Jerry Jeff just might have been, strangely enough, in repose: abed in what his wife, Susan, calls “the Howard Hughes room” of their ranch house outside Austin. There he sometimes relaxes these days with his baby girl, Jessie, at his side, several vials of a restorative ginseng-and-bee-saliva solution handy, an oxygen mask on his face, and, preferably, Monday Night Football on television.

Not that Jerry Jeff has become, by ordinary standards, domestic. After Susan and the baby came home from the hospital, he absented himself to a friend’s house for a while, saying that he didn’t feel quite right at home. When he did show up to take on paternity, he stayed just long enough to voice some firm opinions about how a baby should be held and what a baby ought to listen to. Then he went off on his motorcycle to get some formula and was gone for three days.

Members of the band say he is mellowing. He hardly ever misses gigs anymore. And he drinks less, which says a lot about how much he used to drink. “Like everybody else, he’s getting older,” says Susan, a good-looking woman with flashing eyes who is known to “yell and throw fits,” but who continues, after four years with Jerry Jeff, to regard him steadily, hard-headedly, and with pride. One night he insisted she come up onstage with him as he sang “Derby Day,” his fond tribute to her. So she came to his side, he turned to her in midnote, and she was wearing a wig and an artificial nose.

But Susan loves that song. She doesn’t see how anybody can hear Jerry Jeff’s music and dismiss him as crazy. At the Bottom Line in New York I sat with Susan as Jerry Jeff performed.

“Is he mellowing out?” I asked her.

“Either that,” she said with delight, “or he’s up to something.”

We watched Jerry Jeff working well with his talented rock ’n’ roll band. He had been up drinking for 36 hours, but his set so far was tight; the crowd was loving it; he had a faraway yet engaged, suffering yet grinning look on his beaked, heavy-lidded face; his pot belly was thrusting in tempo; he was unconscious.

When a person is unconscious and singing he is, as Keats put it, “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” The same can often be said of a person who is simply drunk and singing, and Jerry Jeff is often drunk. If he hadn’t been capable of carrying on through uncertainties, he never would have become a Texas legend from Oneonta, New York.

Jerry Jeff was born in that backwater town 37 years ago, under the name of Ronald Clyde Crosby. He shook Oneonta and his name in his late teens, when he took off hitchhiking around the country and making music. Jerry came from his drinking ID, Jeff from (he thinks maybe) the movie star Jeff Chandler, and Walker from either a musician named Kirby Walker or the movie star Robert Walker.

Sometimes he also goes by “Jackie Jack,” a name with an edgy, obsessive, good-time ring. In his early days as a folkie in New Orleans and New York coffeehouses he performed as “Happy Guitar” or “Mr. Bojangles”—the latter name in honor of his best-known composition.

Jerry Jeff is known for raucous country-rock, but he has a penchant for long, overpoetic ballads. He sings about freedom and yet he has frequently gotten himself arrested—25 times, he estimates, for driving while intoxicated alone. People who have played basketball with him or been through tense moments in his company attest to his physical strength, agility, stamina, and daring, but he is famous for falling off stages, and when he gets into a fistfight, as he frequently does, he never hits a man.

Once, when he was getting stomped by a motorcycle gang, he yelled up at his attackers, “You don’t fight as good as rodeo cowboys!’’ Or it may have been the other way around. Or both ways. Jerry Jeff once even nagged pacific Willie Nelson into decking him. He kept picking up Willie’s sacred acoustic guitar, the one with the hole strummed into it over the years, and Willie kept saying, “Leave that alone, Jerry Jeff, I mean it,” and getting madder and madder until he knocked Jerry Jeff, who is considerably larger, flat with one punch. “I remember you,” said Jerry Jeff from the floor. “You’re the one who knocked me down last night.”

“A lot of times, he invites to get hit,” says Bobby Rambo, his lead guitarist.

“But he never hits back,” answers someone else in the band.

“Well, I think he might if he’s right.”

“Yeah, but he’s never right.”

“Well, that’s true.”

Jerry Jeff will hit a woman. His former girlfriend, Murphy, was a strapping and handsome woman who could lick him, but he has been known to hit smaller women, too. There are a number of ways in which Jerry Jeff is not a hero.

However, he is one of the few recorded Americans who have managed to keep anybody from telling them how to record. One company for which he was doing an early album tried to dictate the way it should sound. “I want it to sound like me,” Jerry Jeff said.

“We are not making,” the company man said stiffly, “a demo.”

That was it for Jerry Jeff with that company. Now he gets a budget from whatever firm he has a contract with, and he takes the money to Austin, Luckenbach, Key West, or somewhere. With the help of the band, manager and producer Michael Brovsky, and whatever friends happen along (and, in one case, some chickens), he puts together something that these days is a semiprecious thing: a personal album.

Not necessarily a masterful album. ¡Viva Terlingua!, which has sold over 500,000 copies, sounds very much like it was recorded live in a Luckenbach beer hall, which it was. One whole side of his double-record album, A Man Must Carry On, which has sold over 300,000 copies, is devoted to songs and poems memorializing Hondo Crouch, the mayor of Luckenbach, who died just before the album was released and who was Jerry Jeff’s friend. About the most complimentary thing that can be said about the songs, and especially the poems, is that they are of limited interest. But how many other people in show business would devote a fourth of an album to a dead friend?

Onstage or off, he hates being made to feel self-conscious or observed. “You go somewhere and everybody’s watching you to find out what they ought to start doing after you leave.’’ His response in this kind of social situation is not bland. He was once invited over to a friend’s home for group picking and singing, but on arrival found a lot of people sitting around asking him to “do something.” So he dipped his hat into the host’s big fish tank and began scooping up water and tropical fish and flinging them about the parlor.

Friends of Jerry Jeff’s suggest that he sometimes acts like a cartoon character to preserve his image. “Some other singers get on Jerry Jeff sometimes,” a friend says, “telling him he’s not crazy, he’s not entitled to sing country, he hasn’t been through enough. That probably works on him, that probably pushes him on a little bit. But he’s not crazy. He knows what he’s doing.”

“To us, he’s just one of the band,” says his saxophone player, Tomas Ramirez. For the last three years Jerry Jeff has traveled with a new, improved set of musicians, who not only enjoy him but don’t beat him up or unplug his guitar as did their predecessors, the Lost Gonzos. He also has a new recording contract with Elektra/Asylum, which has convinced the long-suffering Brovsky (who once changed all the locks in his Free Flow Productions offices in Austin so Jerry Jeff couldn’t enter them unilaterally) that this record company regards Jerry Jeff not as a “weirdo” but as a potential superstar.

“There is only so mad you can get at him,” says Ramirez of Jerry Jeff, but some people disagree. Once when he had sat up all night at some friends’ house, the friends’ fourteen- and fifteen-year-old boys, who were about to leave for school, came into the living room to meet their hero. “You’re not really going to school,” said Jerry Jeff, “you’re going to . . .”

“And then he said something really vile,” says the boys’ mother, who is not easily offended. “The boys just stood there. It was awful. You just don’t talk to kids that way.”

Maybe it would have been funny, one kid to another, away from adults. But there are times when a man really ought to be self-conscious enough to acknowledge that in some ways he is grown up. With this in mind I asked him whether having a baby was settling him down. “It’ll probably just make me crazier,” he said. “Because I’ll care more about what I’m doing.” By that he meant getting unconscious.

Before hooking up with Jerry Jeff in Phoenix I had never been on the road with a band of Texas country-rockers. It turned out that Jerry Jeff’s band—Rambo, Ramirez, Ron Cobb, Reese Wynans, Leo LeBlanc, Fred Krc—didn’t look like cowboys at all. They looked like young hippie musicians, except for pedal-steel player LeBlanc, who looked like a cross between a burgermeister and an elf and who wore a porkpie hat with a feather in it. They did whoop, but they also talked a lot about sound systems: monitors, tri-amps, dynamics, twin reverbs, things like that.

The audio texture of Jerry Jeff’s current show is a complicated fabric: the voluminous folds of the electric instruments, the stitching of Jerry Jeff’s between-song mumbles, the burlap of his low notes, the vinyl of his high notes, and what critic Robert Palmer has approvingly called “the frayed living-room rug of his middle range.” And the night I met them backstage in the Celebrity Theatre the sound was not right. The crowd seemed satisfied, but the crowd also seemed stoned, and what Jerry Jeff said between songs was mostly inaudible.

Jerry Jeff has always been known for raggedly unprogrammed music, and his approach is still improvisatory. He and his band have never yet rehearsed. He got them all together for the first time three years ago in a club in Aspen, where they were supposed to have a chance to work out their act. But the owner of the place sold out the house at eight bucks a head, and they had to learn the songs and get to know each other in concert.

Sometimes now a couple of sidemen will grab a moment in between songs to coordinate licks in advance: “There goes the band, arranging again,” Jerry Jeff will tell the crowd with asperity. They never know what songs are going to be played; they just wait until he gets going on one (he doesn’t like to count off) and then come in gamely and free-wheelingly behind him. But the new band takes rock sound more seriously than did the Gonzos, who were more into country fury. The heart of the act, when the act works, is still Jerry Jeff’s earnest or jocular, often slurred but still edgily intended words; the ungainly semigrace of his physical dips and didoes; and his variously imperious, clowning, vexed, meditative, pained, wasted, whoop-de-doing point of view. But the band’s dynamics compensate for the limitations and occasional strayings of Jerry Jeff’s abused vocal equipment, and those dynamics need to be miked right.

“I can go into a jungle joint and relax and play and everybody has a good time,” Jerry Jeff says. ‘‘But in these good places with the good sound systems it’s harder. It’s got to be right.” Jerry Jeff feels more pressure than his image would suggest.

“I ate, I slept, I did everything,” Jerry Jeff griped at one point on the tour. Slowing down long enough to go to bed and have a meal before a show is Jerry Jeff’s idea of monkish propriety. He was damned if he would persist in self-denial if all he was going to get out of it was a show in which he didn’t get unconscious.

So for the next 28 hours or so after the Phoenix show we worked ourselves into a waking dream state. The first thing we did was stay up all night in Jerry Jeff’s motel room debating the following topics: whether Jerry Jeff was going to tour England and Japan and Australia, whether Jerry Jeff was going to appear in New York if he couldn’t get on Saturday Night Live, and whether Jerry Jeff was going to sell his Jaguar and his Mercedes.

A motel security man was on hand, presumably to protect the motel from Jerry Jeff, but he was ignored. So was nearly everyone else except Jerry Jeff, but the debaters included Brovsky and his Free Flow colleague Witt Stewart. The part about the Mercedes and the Jaguar went on for at least four hours, and the only conclusion I derived from it was that the difference between an average country person and a country music star is that the latter has more and fancier cars that won’t crank. Jerry Jeff kept complaining about how many vehicles he had—something like twelve—and that only the pickup worked.

Then the question of whether to go to Japan arose and Jerry Jeff considered the pros—“At least if the band got lost I’d be able to find them in a crowd”—and the cons—“Raw fish! Raw fish!”—and just as it seemed, after an hour or two, that Brovsky and Stewart had talked him into it, he announced with an almost Churchillian resolve, “I still won’t go.” He didn’t care that people adored him in Australia: “I hate adoration! One guy said I was one of the smartest guys he knew and then he jumped right in the middle of my guitar!”

“Well, how about buying an airplane?” Brovsky suggested. “All right,” said Jerry Jeff, “and if it’ll make it to, say, Texarkana we’ll go for Ireland!”

Apparently this is pretty much the way Jerry Jeff works out his business affairs. Recurring motifs this particular night were his feeling that he ought to be marketed at least as broadly as Elton John and his feeling that he didn’t ever again want to leave Texas, where folks accept him as a neighbor.

As he debated, Jerry Jeff blew snot on the floor. I have never been around anyone with such a facility for clearing his nose. “I have a lot of mucus,” he says. “It’s a mannerism. One of those mannerisms people have. I started doing it in motels, on rugs, where it doesn’t make any difference. But in people’s houses, they can’t handle it. I’m trying to wipe it on my leg now.”

Jerry Jeff’s nose is a big part of him. He talks about his “nose for trouble,” and there is no telling how often he has gotten it broken. One of the differences between Jerry Jeff and Willie Nelson is that Willie, for the sake of his voice, preserves his nose. There are students of Jerry Jeff’s music who say his voice hasn’t been the same since he had his fist-and-drug-abused nose fixed a few years back. His nose makes him resemble just faintly—and he won’t like this, having nearly shot out his television a couple of times when the man was on it—Jim Nabors. Jerry Jeff’s nose helps to keep him from looking like a serious cowboy. It doesn’t keep him from ever looking serious, though. As that night in Phoenix wore on, and Jerry Jeff got wearier and more resistant to persuasion, he looked more and more like Billy Martin, the baseball manager, who also has a nose for trouble.

The wrangling went on and on. The band, the road crew, the security man, one by one went off to bed. And the sun rose and the last of the Scotch went down. And those of us who were left wandered out into the dry Arizona daylight and leaned against some of those little trees they have in Arizona, and Jerry Jeff said to Brovsky: “My wife, Susan, who’s so pretty, who’s so smart, who’s only done one thing wrong and that was when she married me, wants to know what I’m going to do! And I can’t look foolish in her eyes.”

Jerry Jeff doesn’t talk readily about his childhood or his parents. He does refute the argument, sometimes advanced by Texas peers, that being from New York he lacks a country-western background: “I did all the same things you guys did. Listened to the Everly Brothers, learned to play ball, and learned to drive a car, and left.”

He didn’t like high school, which he says he never “exactly” finished. “My parents were good people, they paid the bills and did what you have to do. My father worked bars, sold liquor. They were dance champions, traveling around, following music, but when they were nineteen they had me, and quit. They sacrificed. When I got old enough I said, ‘Thank you, good-bye.’ ” His grandfather, who had a square-dance band, is the relative Jerry Jeff speaks of most comfortably. “He’d be lying there, and he’d take off his shoes and attach the ground wire to his toe, and we’d listen to the ball game on the radio.” It was his grandfather about whom he wrote “My Old Man,” which begins,

My old man he had a rounder’s soul

He’d hear an old freight train

then he’d have to go

and ends, sadly and vaguely,

And all that I recall and said when I was young

No one else could really sing the songs he sung. *

Unimpeachable, philosophical, touching, performing, independent old men have been as important in Jerry Jeff’s life and music as cold-hearted women were in Hank Williams’: his grandfather, Mr. Bojangles, Hondo Crouch, even ageless Willie Nelson. These are the people he seems to want to live up to, and he regards them with affection and awe; next to them he is still a kid.

Sometimes he will say to someone slightly his senior, “You’re older than I am, but I’ve been up more hours.” Maybe he is trying to go directly from teenage to old age. His daughter might change that, but Susan says, “He can’t wait for her to be a teenager, so he can get that 1956 T-bird he always wanted.”

And he and his mother still break each other’s hearts. When a story in New Times portrayed Jerry Jeff primarily as a man who pisses in beer pitchers and falls into drum sets while performing, his mother somehow saw it in Oneonta and called him up, crying.

“I told her, ‘Whatever I do… I do what I do… But… just don’t let it hurt you.’ ” That conversation still weighs on his mind.

After a good night of arguing, Jerry Jeff seemed to feel refreshed, and we set out for Tucson at 10 in the morning. Since Tucson is only about 120 miles from Phoenix and the show in Tucson wasn’t until 8:30 that evening, we had a good shot at getting there on time.

But drinking with no sleep eventually puts you on a plane where life is simple and hard. You are doing well to focus on more than about one and a half things at once, so life is simple. You feel as though all your body cavities have been stuffed with oily rags, so life is hard. Most of America’s great music has sprung from conditions that were simple and hard. Even so, you wouldn’t think it would be part of the American dream to re-create painful conditions, but it is; and after you’re on that plane for a while you begin to glide.

We took off in two carloads. The one I was in, with Jerry Jeff and several band members, stopped in several bars before we got out of Phoenix. In one of them Jerry Jeff met a couple of guys, one of whom was named Ape, and he decided to go to another bar with them. Jerry Jeff got in Ape’s friend’s van and headed off, and I jumped in with Ape, who was following them in our rent-a-car. Then I got a good look at Ape. He was a monumental person in a black leather jacket with a lot of long black hair growing out of various parts of his face and head. “You can call me Ape, or the Ape Man,” he said. “No other names.”

Well, when we got to this other bar Jerry Jeff was passed out cold in the van. Shaking him and yelling at him didn’t come anywhere near waking him up. Ape and the other guy and I went into the bar for a while and then we decided for some reason to take Jerry Jeff’s remains over to still another bar. Not until we reached this bar did Ape’s friend, who followed us in the van, inform us that Jerry Jeff was no longer in the van.

Now I had no idea where Jerry Jeff was. I also had no idea where I was. Ape decided something fishy was going on. He jerked his friend the van driver around a little, and then Ape and I went to another bar and visited the homes of a couple of Ape’s friends, one of whom, no doubt quite innocently, kept flicking a big knife open and shut. I think we made a lot of phone calls too. Then we returned to the bar where we’d left the band members and I sheepishly advised them that we had lost Jerry Jeff. “Don’t worry about it!” they chorused. “He does this all the time!”

By now we were running a little late.

I thought we ought to stop by the bar in whose parking lot I had last seen Jerry Jeff. As it happened, we discovered him in that bar, having a reasonably good time drinking with some people who were maybe going to drive him to Tucson.

The next thing I knew Ape was driving the band guys away at a tremendous rate of speed and Jerry Jeff and some other people and I were in another car vaguely Tucson-bound. On the way we drank a good deal from a bottle in which Jerry Jeff had mixed Scotch and ginger ale. None of us knew exactly where the auditorium was. At one point we saw a sign to El Paso. I remember spending what seemed like an hour getting advice in a gas station. Jerry Jeff was not real alert in the back seat.

But we were up, we were up, we were hurtling through the Arizona night heedless, unafraid, amusing, incredibly drunk, and functioning, sort of. Suddenly, against all odds, we hit Tucson, and Jerry Jeff lurched to attention and croaked out directions that had just occurred to him and the next thing I knew we were onstage. The right stage.

Out there in front of us was a big, young, drunk, yelling audience. Jerry Jeff is ambivalent about his audiences. “Sometimes they get too drunk,” he says. And they are too young. And they are not sufficiently discriminating. His band says he wishes that his audiences would shut up and listen, the way Willie’s do, when he shifts from one of his hard-driving rousers to a tender ballad. Once, before a performance, he accidentally took some synthetic marijuana (something he eschews even in natural form, because it makes him sleepy). “Great,” said the promoter afterward. For once Jerry Jeff was taken aback. “But I was hopping like a kangaroo!” he said. “That’s what they like,” said the promoter.

In Tucson, Jerry Jeff was geared for that kind of audience. He played “Redneck Mother.” He played “London Homesick Blues.” He played “Hill Country Rain,” with those words that come to mind whenever I think about Jerry Jeff:

I’ve got a feeling

Something that I can’t explain. . .

He played “Pissin’ in the Wind” twice. The crowd seemed to be having the best time anybody had had in Tucson in years.

That was my impression, at least. I was unconscious onstage. Jerry Jeff believes I sang in the show, on “There Ain’t No Instant Replays in the Football Game of Life,’’ but since I can’t sing and don’t know the words to that song, I doubt it. I may well have hummed along, because I remember a certain amount of consternation and murmurs of “What mike is he on?” arising among the band.

As for Jerry Jeff, he played his electric guitar for the folks so hard that his untaped broken right hand (he fractured it punching a storm-glass window after “seeing too many rainbows” in Hawaii) got all ripped up. Critic Mary Freeman’s review in the Tucson Citizen the next morning carried this headline: JERRY JEFF’S SOT IMAGE EXPOSED BY PERFECT SHOW. The review said in part, “Jerry Jeff Walker scrounged up his grungiest denims, staggered in through the side door an hour late, and generally worked hard at maintaining his ‘image’ for some 1500 at the Tucson Community Center Music Hall last night.

“By 8:30 p.m., with no signs of life coming from the stage, rumors began to buzz: ‘Jerry Jeff’s… drunk somewhere, you know how he is!’

“At 9 p.m. his band started up. Bobby Randall [Rambo] took the lead. . . . ‘He’s somewhere between here and Phoenix,’ Randall assured the crowd. . . . Guess who wandered in from the side exit? The crowd went wild. J. J. staggered; he kept his back to the audience. ‘Boy is he blitzed . . . really stoned.’

“Jerry Jeff Walker was a fraud last night. Stoned? Yes, stone-cold sober. It was an act; it was part of the image; it was all for a good time. Everybody got his money’s worth.” (This last sentence particularly amused the troupe the next day, inasmuch as the promoter had left without paying them.)

“A more perfectly staged and timed show has rarely been seen by these eyes.

“Walker had his voice tuned down to its gravelliest… In his studied uncoordination, he bumbled and mumbled… He played the part to the hilt. He kept a benign, stupid grin on his face from start to finish, oozing the charm usually reserved for the truly besotted.”

Well, that review tickled Jerry Jeff and his troupers no end. The show had not in fact been what you could call musically tight, and it had been truly besotted. But there was something fitting about the review anyway. Some insoluble compound of Jerry Jeff and his image had come through the wreckage. I think Jerry Jeff had got unconscious.

*©1968 Cotillion Music, Inc., and Danel Music.

- More About:

- Music

- Longreads

- Willie Nelson

- Jerry Jeff Walker