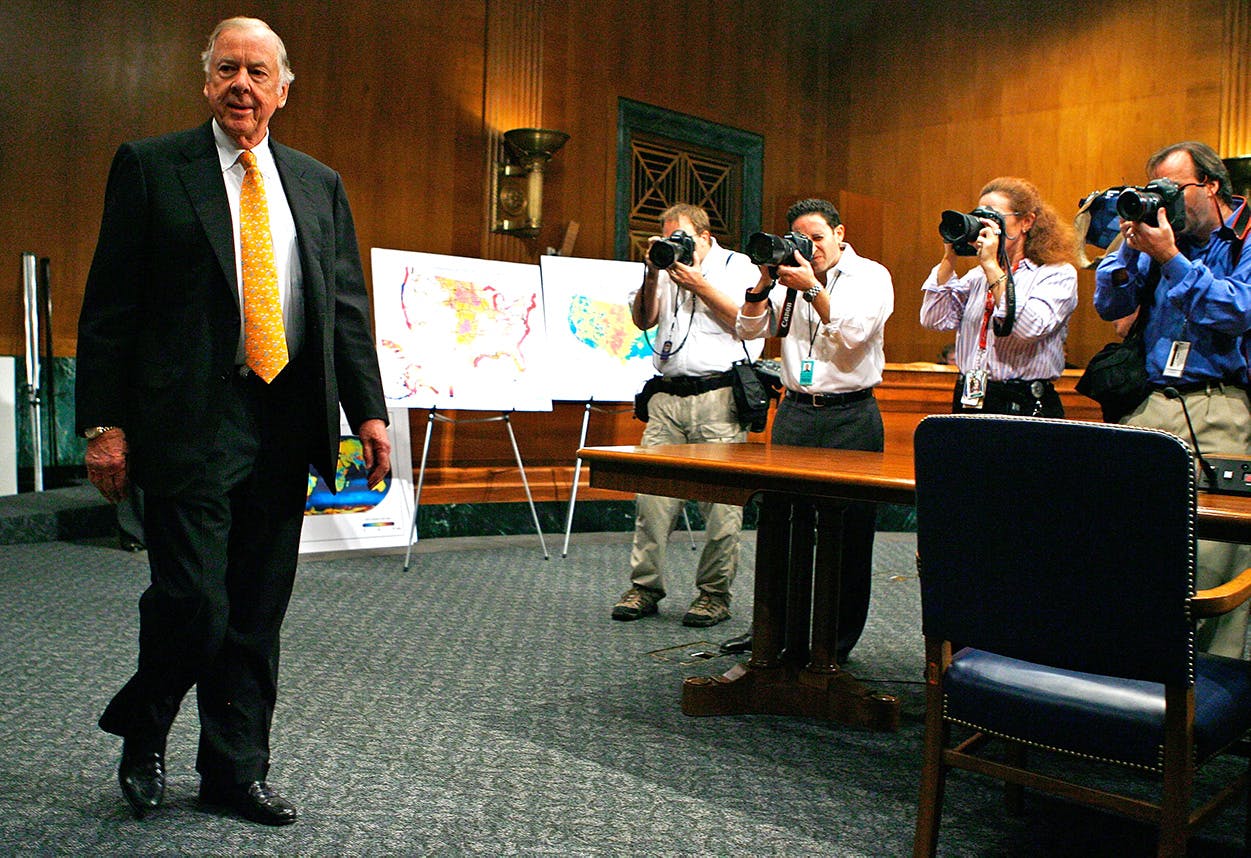

It was July 8 in New York City and eighty-year-old T. Boone Pickens was, once again, the toast of the town. Wearing wraparound Ray-Bans and a gray pin-striped oxford suit, he strolled into the ornate Palace Hotel, stopped to shake hands with some well-wishers in the lobby—“Hey, Mr. Pickens, what an honor!” bellowed one businessman, his eyes widening as if he were meeting a head of state—and bounded upstairs to a banquet room, where a couple dozen journalists and photographers were gathered to hear his plan to save America from its addiction to foreign oil. Boone had spent more than an hour that morning chatting about the plan on CNBC, and he had also appeared on ABC’s Good Morning America and NPR’s Morning Edition. Later that day, he was scheduled to meet with CNN, Fox, and the BBC, followed by visits to the offices of the Associated Press, the Wall Street Journal, and the CBS Evening News, where Katie Couric herself had decided to interview him for that night’s newscast.

“Now, listen to me, we’re in a ditch,” Boone told the reporters in his slow, gravelly drawl. “We’ve got all these politicians talking about better health care and what all, but believe me, we’re not going to have the money to take care of sick people—or anyone else as far as I’m concerned—if we don’t fix our energy problem right now. I’ve got an idea what to do. It might not be a perfect idea, but hell, none of my best ideas have been perfect.”

The reporters started grinning. Sitting in the back of the room, I couldn’t help but grin too. I found myself thinking about another occasion more than a decade ago when I had watched Boone. He was eating dinner with some business associates at the popular Dallas restaurant Bob’s Steak and Chop House, and his trademark boyish smile was wiped from his face. Just a few months earlier, he had been forced out of Mesa Petroleum, the oil and gas exploration company he had started in 1964. He had formed BP Capital, a hedge fund that specialized in oil and natural gas commodities, shortly after his Mesa exit, but it was already on the rocks. Younger investors considered him a has-been. Even Bea, his wife of 24 years, had given up on Boone. She had launched a full-scale assault on his $78 million fortune in divorce court, going so far as to demand full custody of their dog, a brown-eyed papillon named Winston. That night, as I watched Boone walk out of the restaurant carrying a little bag containing his half-eaten steak, I found myself shaking my head, actually feeling sorry for him. I leaned over to a friend and said, “The great titan has fallen.”

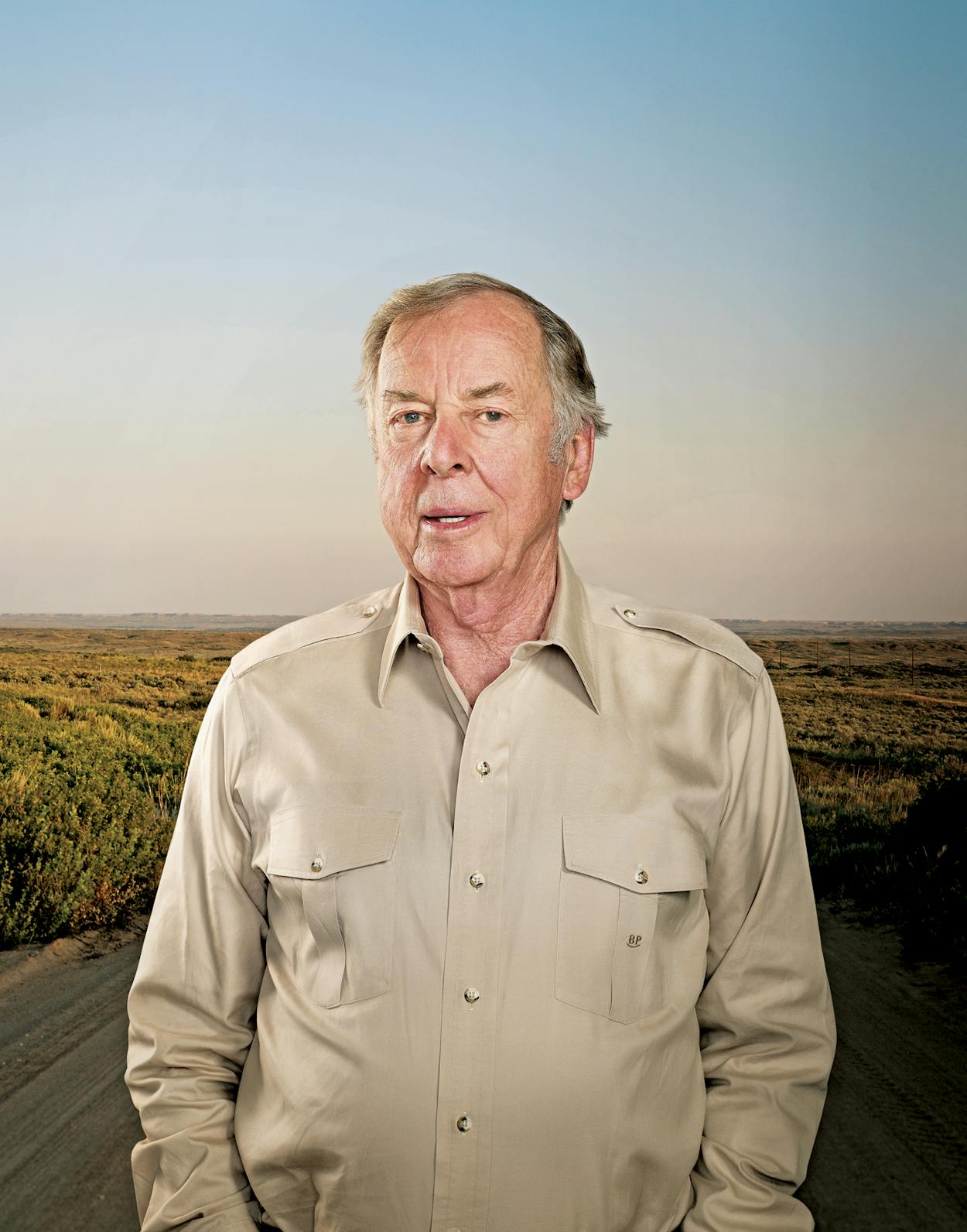

Boy, did I get it wrong. Just about all of us did. Due largely to some audacious bets he started making in 2000 with his hedge fund, throwing almost all of his and his clients’ money into long-term oil and gas futures contracts well before energy prices began to take off, Boone is now wealthier than perhaps even he thought possible, his net worth at a stunning $4 billion. He is also, in the words of one of his colleagues, “back to making more deals than there are days of the week.” Besides his usual oil and gas plays, he’s bought nearly 400,000 acres of water rights in the Panhandle, giving him control of billions of gallons of water, which he hopes to sell to Dallas and Fort Worth and their surrounding suburbs at a profit of tens of millions of dollars a year. What’s more, he’s started work on what he calls “the biggest deal” of his career: the construction of the world’s largest wind-energy farm, containing as many as two thousand turbines spread over five Panhandle counties that will generate enough electricity to power more than 1.3 million homes.

And now there is his $58 million national advertising campaign to promote his energy policy, which he is calling the Pickens Plan. You’ve no doubt seen Boone’s full-page newspaper advertisements or watched his television commercials in which he states, “I’ve been an oilman my whole life, but this is one emergency we can’t drill our way out of.” You probably have seen him on his Web site or on television shows, standing before a whiteboard, scribbling all over it like a mad professor as he declares that the United States is spending $700 billion a year on foreign oil—“the largest transfer of wealth in the history of mankind,” he always points out. And if nothing is done, the country could very well be spending $10 trillion on foreign oil within a decade.

You’ve also heard about his solution, in which he wants other entrepreneurs and energy companies to build wind farms like the one he’s constructing in the Wind Belt: the vast corridor that extends the length of the Great Plains, from Texas to the Canadian border. He wants the power that will come from those wind farms to replace the natural gas that we now use to make electricity. (About 22 percent of America’s electricity comes from natural gas, 50 percent from coal, 20 percent from nuclear power, and the rest from other sources.) In turn, he wants to use that natural gas as fuel for automobiles—all of which, he says, will lead to a significant drop in gasoline use and a 30 to 40 percent reduction in our oil imports, saving close to $300 billion a year.

For a man who’s known for his right-wing leanings—he is the guy, after all, who in 2004 helped fund the campaign by the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth to discredit John Kerry—Boone is suddenly acting like the greenest of Democrats. What’s more, he’s putting his money where his mouth is. In addition to his wind farm, which will cost $10 billion to build, he’s also the founder and majority stockholder of California-based Clean Energy Fuels, which markets natural gas for buses, airport shuttles, and taxis. “There are more than seven million natural gas-powered vehicles on the road worldwide, but only 150,000 or so in the United States, which doesn’t make a lick of sense whatsoever,” he told me. “Natural gas is cheaper and cleaner than gasoline, and it all comes from fields right here in our own backyard, not over there in the Mideast.”

Boone is even willing to talk about a subject that is considered heresy in his line of work: global warming. “Oh, what the hell, what would be all that bad about reducing our carbon footprint?” he asked me one day, which prompted me to think, “Did I really just hear Boone Pickens use the phrase ‘carbon footprint’?” Although he insists he is not turning into a Democrat—“I’ve never voted for a Democrat for president, and I’m not going to start now,” he said, looking at me as if I were an idiot when I dared to suggest that he might mark his ballot for Barack Obama—he does say that he would be more than happy to sit down with both Obama and John McCain to tell them about his plan. “So far, neither one of them seems to have any idea that energy has got to be the number one issue of this election,” he said. “So if they’re not going to talk about it, then I guess I better damn well start.”

In addition to the advertising campaign, Boone is also laying out his energy manifesto in his latest memoir, The First Billion Is the Hardest, which Crown is releasing this month. (His first memoir, Boone, was published in 1987.) “The times require a George Patton, someone who can lead us to victory no matter the obstacles,” he writes, adding that the president should appoint an energy czar who “would be empowered to be decisive, to act fast, and to fix this problem.”

And does Boone believe that this particular Patton should be none other than Boone himself? In every interview he gives, he adamantly says no, but a lot of people are convinced that the old wheeler-dealer would be perfect for the role. In fact, when I was with him in New York, I was amazed by the way he enthralled a new generation of reporters—almost exactly the same way he enthralled a generation of reporters when he was running Mesa in the eighties and coming to New York to make his quixotic takeover attempts of such Big Oil behemoths as Gulf. On Good Morning America, after he spouted off one of his well-known Boone-isms, as he refers to his folksy sayings, he told host Chris Cuomo about America’s existing energy policies, “A fool with a plan is better than a genius with no plan, and we look like fools without a plan.” Cuomo unabashedly shook his head in admiration and said to Diane Sawyer, “What a great line.” (Sawyer later added, “I just like to say, ‘T. Boone’!”) During his CNBC appearance, anchor Becky Quick, who was wearing an orange scarf around her neck in homage to Boone’s alma mater, Oklahoma State University (the other CNBC anchor was wearing an orange tie), asked him if he would consider making an independent run for president or be a candidate for vice president. (“No, Becky,” he chortled.) And when he finished his press conference at the Palace Hotel, some of the reporters actually burst into applause. A bearded young television cameraman in shorts said to Boone just before he walked out of the room, “Wow, like, what can I do to get my car to run on natural gas right now?”

As odd as it seems, Boone is, in the words of longtime lawyer and confidant Bobby Stillwell, “hitting his prime once again—an eighty-year-old going on thirty.” He even has a glamorous new wife, the former Madeleine Paulson, a sassy, 61-year-old blonde with a refined English accent who is the widow of Gulfstream Aerospace founder Allen Paulson. Wealthy in her own right—she owns the Del Mar Country Club, in California, a slew of championship racehorses, and a $35 million beach estate—Madeleine could probably have grabbed any available billionaire she wanted after her husband’s death, in 2000. “But when I met Boone in 2005, I knew I had found my John Wayne,” she told me one afternoon while I flew with the couple on their $57 million Gulfstream G550 corporate jet.

“We’re having such a good time that we’ve been talking about starting a family,” Boone said, the look on his face completely serious.

“Yes, we’re working very hard to have one,” Madeleine added, giving me an equally serious look, her perfectly plucked eyebrows rising slightly. “We’re trying every night.”

I stared at them, unsure what to say, until they both started laughing.

“The way things have been going, who the hell knows?” Boone said. “Who the hell knows?”

To be honest, there are plenty of signs that Boone is eighty years old. He’s hard of hearing. His eye muscles are weakening, which makes it difficult for him to read. Because of his poor eyesight, he’s also had to cut back on his beloved dove and quail hunting.

But he still exercises every weekday morning—his trainer shows up at his mansion in the Preston Hollow estates area of North Dallas at 6:30 and puts Boone through a rigorous 45-minute workout—and he’s always at his office, which is less than half a mile from his house, by 8:00. He doesn’t drink coffee (he loves to tell his younger employees that he’s never spent a dime at Starbucks), but he does nurse a Diet Coke or Diet Dr Pepper throughout the day. “I’ve told him he probably could afford to pop open a second soft drink after the first one gets warm,” his wry administrative assistant, Sally Geymüller, who’s been working for him since 1979, told me. “But Mr. Pickens doesn’t like to waste a penny. Just watch him whenever he walks out of a room. He always turns out the lights.”

BP Capital occupies the second floor of a high-end office building just off Preston Road. Only 35 people work there. The entire setting is almost ridiculously informal: One afternoon when I was visiting, I watched Geymüller’s seven-year-old son, dressed in his baseball uniform, lie on the carpet waving his arms in the air while executives stepped over him on their way to a meeting. Then along came Boone’s dog Murdock (another brown-eyed papillon; Boone did lose his first dog in the divorce), trotting from one room to another, looking for snacks.

At the office, Boone himself rarely wears a tie. His usual outfit consists of a button-down shirt, pressed slacks, alligator loafers, and a Rolex that he bought in 1964 for $750. Unlike most CEOs, he doesn’t maintain a minute-by-minute schedule. He carries around a tiny calendar in his back pocket, but on the day I saw it, the pages were barely filled up. He seems to spend most of his time on the phone, talking to Wall Street insiders like Ace Greenberg, the former CEO of Bear Stearns (“Ol’ Ace,” Boone calls him), other billionaire investors such as Warren Buffett (“Ol’ Warren”), or Madeleine (“Ol’ Madeleine”). He constantly checks in with his own analysts and traders, who work down the hall from him, and at least twice a day he meets in the boardroom with his entire investment team, made up of ten to twelve men, half of whom are in their early thirties. (As soon as the market closes at three o’clock, a few of those younger guys throw on shorts and T-shirts and run across the street to a Catholic church to play basketball on an outdoor court; then they race back to the office, where they shower and put on their golf shirts and chinos in time for a late-afternoon meeting with Boone.)

In one meeting I attended, Boone sat toward the front of the room, a black cape draped over the top half of his body. He was getting his hair cut by his longtime barber, Keith Clark, and Clark’s wife, Frances (who now does most of the work on Boone’s hair because of the 68-year-old Keith’s fading eyesight). As Keith and Frances studied his sideburns to make sure they were even—“Real, real nice,” said Keith—Boone looked at his guys and asked simply, “What you got?”

It was part think tank and part bull session as everyone began throwing out bits of information that could possibly affect the fortune of Pickens’s hedge fund (BP Capital has approximately $4 billion under management) or any of his other projects. Boone constantly asked questions. He asked about the prospects of one company that was drilling for natural gas in the Barnett Shale, and he asked about the progress of another company’s solar energy project in Florida. He asked if anyone knew about a report that gas storage levels were down in the United Kingdom. Then he suddenly switched subjects to talk about a documentary he had seen on the Discovery Channel about pipe insulation, then he just as suddenly switched subjects again to discuss some complicated accounting concepts regarding the front-loading of taxes on the hedge fund. At one point during the meeting, when everyone was talking about an offshore oil drilling project, Boone leaned forward, spotted me taking notes in the back of the room, and said, “What do you think over there, Ol’ Skip?”

For the first time, I understood why Forbes magazine had sent along a reporter this spring to watch Boone have his brain analyzed at the University of Texas at Dallas Center for BrainHealth. (The scientist who studied him exclaimed to the reporter, “Mr. Pickens’s brain activated in places that young brains activate!”) “His mind really is like a sponge,” said Brian Bradshaw, a 32-year-old analyst for BP Capital. “He forgets nothing, and considering all his experience in this business, he still wants to know what other people are thinking. But he also knows when to tune out all the noise and make a decision. During a meeting, we’ll throw out five or six reports that suggest we shouldn’t make a particular investment, and after a while, he’ll shrug and say, ‘No, we’re going forward. Our strategy is right, and we’re not changing.’ He’s got ice in his veins.”

Boone, of course, has always loved playing the role of the contrarian. The son of an oil-patch land man, he was born in Oklahoma, moved to Amarillo during high school, went to work for a couple of years as a geologist for Phillips Petroleum after his graduation from Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State), and then impulsively struck out on his own in 1954, when he was just 26, soon forming an Amarillo-based exploration company with only $2,500 in borrowed money. By the late seventies, he had turned the company, which was then known as Mesa Petroleum, into perhaps the most successful independent in the country. In one of his most profitable plays, he invested $35,000 into drilling sites in Canada, sank the money from those sites into new wells, and in 1979 sold his entire Canadian operation to another oil company for $600 million.

Then, in the early eighties, he made a peculiar statement to his board of directors: “Fellas, it’s cheaper to drill on the New York Stock Exchange.” At the time, it didn’t exactly strike anyone as the kind of line that would one day be studied in business schools: What in the world did a folksy wildcatter from Texas know about the intricate machinations of Wall Street? But Boone persuaded the board to let him use Mesa’s money to buy stock in publicly held oil companies that he believed were undervalued and poorly managed. After he accumulated 10 percent or so of stock in one of them, he pounced, calling a press conference to announce that he would be attempting to get controlling interest in the company so that he could bring in a new team of executives who cared more about their shareholders than about their perks. He once famously proclaimed that Big Oil executives “have no more feeling for the average stockholder than they do for baboons in Africa.”

He was one of the first barbarians at the gate, his raids on Gulf Oil, Phillips Petroleum, Cities Services, and Unocal so stunning that he landed on the front pages of hundreds of newspapers, as well as on the covers of such magazines as Time and Fortune (and Texas Monthly, in 1982). Although he never acquired any of the companies he targeted, he brought almost all of them to their knees, forcing them to merge with other companies just to keep him away. As a result, he did, as promised, increase the value of the stock of those companies, reaping millions for their shareholders and millions more for Mesa. (From 1982 to 1985, Mesa made at least $800 million off its takeover battles.) To prove that he really was the kind of CEO who put his shareholders first, he also issued large distributions to Mesa’s own shareholders.

He then used much of Mesa’s earnings to purchase huge reserves of natural gas because he believed that the price was about to go up. It was a spectacular miscalculation. Gas prices declined, Mesa became saddled with $1.2 billion in debt, and the company itself became a target of its own corporate raider. Incredibly enough, the raider was David Batchelder, a former Mesa executive and a Pickens takeover protégé.

Boone ultimately blocked Batchelder’s move by arranging for former Fort Worth financier Richard Rainwater (who once oversaw the Bass brothers’ financial holdings) to invest as much as $265 million on preferential terms that essentially gave Rainwater control of Mesa. Although Rainwater initially said he wanted Boone to run the company, a plan was soon formed to push him out. Boone told me that in May 1996, Rainwater invited him to his estate in Santa Barbara, California, where he was then sent off to have iced tea with Rainwater’s wife, Darla Moore, who had once been a feared executive at Chemical Bank. According to Boone, Moore promptly informed him that he “hadn’t kept up” with the times in the oil and gas industry and that he should leave Mesa.

Boone was then 68 years old. “It was a devastating moment for him,” recalled Stillwell. “Darla and Richard didn’t treat him well, and Darla went so far as to insult him. I’ll never forget, after that meeting with Darla, he looked at me and quietly said, ‘They don’t want me.’”

To add to his problems, his marriage to Bea, whom he once described as “the perfect deal,” was going south. (Boone had already been divorced before.) According to word on the street, he spent $10 million in legal fees fighting Bea in court. When they finally settled, he was left with about $34 million in cash and assets—peanuts for someone like him.

In September 1996, a mere four months after his unceremonious exit from Mesa, he formed BP Capital, which consisted of just Boone and five employees, all of whom worked out of a modest leased office that contained used furniture. He drove to a government building in North Dallas to take the National Futures Association examination. A young man walked up to him and asked what he was doing there. “Hell, trying to get by like everyone else,” Boone told him.

After failing twice, he finally passed the test, and he went looking for investors for his hedge fund. He raised about $40 million—$10 million from his own pocket, with most of the rest coming from rich old pals like Fayez Sarofim, of Houston, and Harold Simmons, of Dallas. But almost immediately, Boone made another bad call, going short on natural gas contracts, betting that prices would drop, which they did not. From July to November 1997, the fund was losing at least $1 million a month—in November it lost $13.3 million—and by January 1999, it was down to only $2.7 million. “I was scratching a poor man’s ass,” Boone said.

People who were around Boone during those days say he was definitely off his game. His sense of humor was gone, and he snapped at his underlings in the office. When I told him about seeing him at Bob’s Steak and Chop House—the truth was that a lot of Dallas people dropped in at Bob’s just to get a look at him—he said, “Yeah, it wasn’t my finest hour. Most nights, I went with my divorce attorney, and I didn’t have much of an appetite. I ended up with about twenty doggie bags of steaks in my freezer.”

At one point, Boone’s lawyer worried that he was suffering from clinical depression. Boone said that he met with a psychiatrist, whom he described as “one of those intellectuals,” and took antidepressants for about a month. “But I didn’t have any desire to slow down and take a vacation like some people were telling me to do. I still wanted to run with the big dogs. And if you’re going to run with the big dogs, you’ve got to get out from underneath the porch.”

He did make a couple of attempts at being the old barbarian. On one occasion, he bought stock in a small publicly held oil company in Tulsa and paid a visit to the chief executive officer. But the CEO didn’t even let him come through the main reception area, sending him instead into an office through a side door. Boone gave him his standard spiel—“I said, ‘I’ve got a lot of money invested with you, and I think the company needs to change for the good of the shareholders’”—and the executive promptly escorted Boone right out of the office. He knew Boone didn’t have the financial backing to mount a takeover.

“After that, did you consider giving up?” I asked.

Boone gave me a look, his eyes narrowing. “You think the phrase ‘giving up’ is in my vocabulary?”

In early 2000, Boone made his make-or-break gamble, telling his brokers to take almost all the money they had left and buy long on natural gas. The price, he said, had to be going up. This time, he was right: By November, natural gas had jumped from $2 to $4.50 per thousand cubic feet, and a month later it was at $10.10. In a single year, the hedge fund was up $252 million, a gain of 9,905 percent before fees. Boone then reversed course in early 2001, taking his position from long to short, right before the price of natural gas began to plummet, and in 2002, he just as quickly went back to buying long, right before a tropical storm and a hurricane shut down much of the offshore natural gas production and sent prices soaring once again. He was still buying long in early 2003, when massive winter storms hit the United States, causing another spike in prices.

Meanwhile, he was making similar moves with his oil trading. In December 2003, when Wall Street experts were claiming oil prices had topped out after having gone up 50 percent in the previous six months, from $20 to $30 a barrel, Boone ordered his brokers to buy long on every contract they could find. He ordered them to continue doing so in October 2004, when oil hit $50 a barrel, and in 2005 he still had them buying long, purchasing futures contracts as far out as ten years. At his daily meetings with his investment team, he insisted that the world had reached peak oil, meaning that the total production of oil could no longer keep up with the world’s demand. He said that OPEC’s claim about having plenty of extra reserves to handle the rocketing need for oil (especially from China and India) was absurd, and he was especially adamant that U.S. oil companies were unable to make up the difference. He said that Big Oil’s hopes of finding billions of barrels of oil offshore or in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was “their last kiss at the pig.” The price of oil, he said, was going to soar past $100 a barrel.

At the end of 2005, his hedge fund was up $1.3 billion, and a second BP Capital fund that invested in energy companies was up $532 million. At a Christmas luncheon, Boone passed out $50 million in bonus checks to his employees. Based on the returns he received from his own investments, along with the fees he made from managing the hedge fund, his income for 2005 was around $1.5 billion. (He paid the IRS $279 million in taxes.) Once again, Boone was being celebrated in the media, getting headlines like “Return of the Raider,” “The Resurrection of T. Boone Pickens,” and “Comeback Kid.” The New York Post ran an illustration of Boone dressed as a swami, accurately predicting the future price of oil.

“And your depression? Did your comeback help get rid of your depression?” I asked him.

“Depression?” Boone said, giving me the trademark grin. “Man, my depression was out the door and down the road.”

With his new fortune, Boone had become a world-class philanthropist, bestowing hundreds of millions of dollars upon Oklahoma State, hospitals, and numerous charities. Of course, Boone being Boone, he doesn’t give away his money like a typical tycoon. When he wrote a $100 million check to the University of Texas System (split between the UT Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas, and the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, in Houston), he stipulated that both institutions had to invest the money and grow it to $1 billion ($500 million each) within 25 years. Otherwise, Boone said, they had to give whatever profit they made on his original investment to Oklahoma State. “You know they’re going to grow that money,” Boone told me. “UT is never going to write a check to Oklahoma State for anything.”

He had also used his fortune to transform his dusty 68,000-acre Panhandle ranch, Mesa Vista, into an oasis filled with man-made lakes, creeks, and waterfalls, plus more than ten thousand trees trucked in from as far away as Colorado, Illinois, and Tennessee. His ranch house, which is at least 11,000 square feet, looks more like a castle—the Dallas Morning News society columnist Alan Peppard once described the place as “Hearstian”—and there is a seven-bedroom guest lodge, as well as a two-story kennel for the hunting dogs that is bigger than anything I have ever lived in.

It was Peppard who, after meeting Madeleine at a luncheon in Kentucky, suggested to Boone that he take her out on a date. Boone, however, was just coming off another marriage—right after his divorce from Bea, he had wedded a Dallas woman whom Condé Nast Portfolio magazine would later describe as “a voluble divorcée”—and he wasn’t certain he wanted to jump into another relationship. “Besides,” he told me, “I had never dated a woman outside Texas or Oklahoma.” Born in Iraq, where her father, a native Englishman, worked in a minor position for an oil company, Madeleine spent her youth in English boarding schools, where she learned to speak in a distinctly non-Texan manner, pronouncing the word “either,” for instance, as “eye-ther.” Perhaps most disturbing to Boone was that she was a vegetarian. He had no idea what she was going to eat if he ever took her to Bob’s.

He flew her to the ranch anyway. When she walked through the front door, dressed to the nines, he turned to a friend standing beside him and said, “Uh-oh.” Within three months, they married at her California home, and he gave her a heart-shaped wedding ring that was the size of a small atomic bomb. “I knew Madeleine already had some big jewelry,” Boone said, “but I wasn’t going to be out-ringed.”

To his friends’ astonishment, he was genuinely head over heels. He went to Congress to testify for one of Madeleine’s favorite causes—the abolition of horse-slaughtering plants—and after Hurricane Katrina, he funded another one of her passions: the rescue of some eight hundred stranded dogs and cats from New Orleans, which he loaded onto a cargo plane and flew to new homes in Colorado and California. He even decided to give up his cherished 1997 blue BMW (which he called, predictably, “Ol’ Bluey”) and ended up with a top-of-the-line Mercedes because Madeleine thought he’d look good in one.

In turn, Madeleine treated him like royalty. For his eightieth birthday party earlier this year, she rented out the entire Dallas Country Club, covered the walls with photos of his ranch, and hired comedian Dennis Miller to be the party’s emcee. (Miller’s best line: “Boone is one of the few people who can watch Giant and think it’s a home movie.”) For entertainment, she flew in the blind Italian tenor Andrea Bocelli, British soprano Sarah Brightman, American Idol star Katharine McPhee, and Belgian singer Lara Fabian, whom Madeleine described as “better than Streisand.” They performed their various hits and, for the finale, gathered onstage and sang “My Way” while they gazed fondly at Boone (well, all of them, that is, except Bocelli).

“Good Lord, that sounds over the top,” I said to Madeleine when she recounted the evening.

“Hey, it was a festival of love,” she gaily replied. “I wanted the best to sing to the best.”

When I turned to Boone and asked if he was a big fan of those singers, especially that Fabian woman, he glanced at his wife, nodded, and said, “Oh, yeah, I really like their music.” I tried not to laugh. I knew he was telling a big old fib.

But it must be said that Boone has changed Madeleine in plenty of ways as well. When I watched her shopping one afternoon at the Neiman Marcus in Newport Beach, California, while Boone was attending a meeting, she squealed in delight when she came across a garish bright-orange handbag (price: $1,475) that in her previous life she wouldn’t have looked at twice. “This will be perfect for our trips to Oklahoma State,” she said. And what’s particularly amazing is that she can now do Boone’s energy speech just about as well as Boone can. On one occasion when I was with them, Boone suddenly stopped talking about the Pickens Plan so he could take a phone call to talk to one of his brokers, and she stepped right in and said, “It’s absolutely insulting what these politicians are doing, selling a pipe dream to the public about oil. They should have listened to my dear Boone years ago.”

Boone claims he’s been trying to get politicians to listen to him about energy since 1996, when he was asked to be the Texas chairman of Bob Dole’s presidential campaign. During a meeting with the candidate, Boone fired off his ideas to break the country’s addiction to foreign oil. According to Boone, Dole replied, “My friend, let me give you a lesson about politics. One thing you don’t do in politics is kick a sleeping dog, and energy is a sleeping dog. If Bill Clinton doesn’t mention energy, I’m not going to mention it, and that’s that.”

Nevertheless, Boone said, he kept trying. Last year, he told Rudolph Giuliani he would support him for president only if Giuliani would meet with him to discuss his energy plan. “He gave me all of five minutes,” said a disgusted Boone, who later wrote a letter to all of his friends whom he had asked to support Giuliani, apologizing for directing them to a candidate “who rode up to the grandstand and fell off his horse.”

Earlier this year, he went to visit President George W. Bush at the White House, bringing with him the whiteboard that he carries on his jet. Standing before Bush, marking all over the board with a black pen, he gave the president his speech: Total global production of oil was at 85 million barrels a day, total global demand was hitting 87 million barrels a day, and oil producers were unable to make up the difference. The hydrocarbon era—the very era that had made Boone a rich man (and, by the way, also made Bush a millionaire)—was over, Boone proclaimed. The age of alternative energy must begin immediately.

“And what did the president say?” I asked.

“He said, ‘No shit! T. Boone, you’ve got to be shitting me!’”

I started writing down everything Boone had said.

“Oh, hell, come on, you know I’m kidding,” Boone said. “The president politely told me that what I had to say was very, very interesting.”

“In other words, your talk didn’t affect him all that much.”

Boone then said something pretty frank for a big-time Republican. “Well, he hasn’t done anything so far, has he?”

It was in May, not long after his meeting with Bush, that Boone decided to take his Pickens Plan to the public. When he signed off on its $58 million budget, which could very well be the most expensive public policy ad campaign ever funded by a single individual, his public relations man, Jay Rosser, told him that his face would probably be seen this fall on television commercials as frequently as McCain’s and Obama’s. Boone said that wasn’t good enough. He also wanted to hit the road, he said, giving his whiteboard presentation to just about anybody who would listen.

One afternoon, I went along with some other reporters to hear him talk to about three hundred residents of Pampa, the Panhandle town that will be at the epicenter of Boone’s wind farm. On the way there, a young reporter from Wired, the high-tech magazine, told Boone she had watched several episodes of Dallas, featuring none other than the character of J. R. Ewing, to prepare for her meeting him. Boone stared at her in bewilderment. She told him she wanted to know about the early days of the oil industry.

“Well, to be honest with you, I was one of H. L. Hunt’s illegitimate children,” he said, his expression totally deadpan. “I came from his fourth family.”

This time, the reporter gave him a bewildered look. “Really?” she said.

Standing at a podium at the Pampa civic center, Boone fiddled for a while with his lapel microphone and then said, “Are y’all hearing a damn thing I’m saying?” Everyone roared with laughter. He then announced that he had just written a check for about $150 million as his down payment to purchase his first 667 wind turbines, each the size of a 48-story building. He openly admitted that none of the wind turbines would be placed on his nearby ranch “because I think they’re ugly as hell. But any of you who wants to put one on your ranch will get about ten to twenty thousand dollars a year in royalties from us. Pampa is on its way to becoming the wind capital of the world!” Everyone applauded until their hands were sore.

Afterward, people gathered around him, saying things like, “We sure do appreciate you, Boone. We do, we do.” One older man walked up to remind him about their years playing high school basketball together. Boone not only remembered the man’s name, but he also remembered the names of everyone on the team. An immigrant from India who owns a Pampa motel asked Boone whether he should build a second one to prepare for the 1,500 or so workers who would be arriving to construct the turbines, and a woman said she was worried she wouldn’t be able to irrigate her crops with a wind turbine “stuck smack-dab” in the middle of her field. Boone grabbed a sheet of paper and sketched out a diagram showing how the irrigation would work. “Okay, we’ve solved it,” Boone said to her. “Now, go sign my lease. We’re going to make you some money, and we’re going to make me some money too.”

Boone’s critics—and there are plenty of them—say that such a statement only indicates Boone’s ultimate motive for his various projects: to make himself even richer. Some residents in the Panhandle are livid about his plan to send their water to Dallas, claiming that he will inevitably drain the valuable Ogallala Aquifer. (Boone’s experts insist that the aquifer will not be harmed.) Others are hopping mad that his lobbyists slipped an amendment on a water bill through the state legislature that gives him the power of eminent domain to obtain the right-of-way through private property to build a 328-mile water pipeline and electric transmission lines from the Panhandle to the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

And there are skeptics who believe the Pickens Plan is nothing more than a scheme to benefit his own wind farm and natural gas company—“his way of filling his own pocketbook,” snapped Thomas “Smitty” Smith, the director of Texas operations for the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen. At the press conference in New York, an Associated Press reporter asked Boone, “Is this not a conflict of interest? Let’s say there’s an arms manufacturer announcing that America is facing a serious war and that the only answer is to buy his weapons. Would you really trust what he’s saying?”

Boone didn’t hesitate. “Sure, I’d like to make a profit on the wind farm, but do you really think I’m doing this because I need more money?” he said. “In the next ten years, this country is going to need a fifteen percent increase in the amount of energy that we use now, and do we really want it to come from foreign oil? Do we really want to just sit here and keep doing nothing? I want people to look at me and say, ‘That old fart, he’s eighty years old, he’s out there still plugging, putting those wind turbines up at his age, and if he can do it, I can do it too.’”

Experts are still not convinced wind energy can become a major source of electricity for the United States. So far, wind supplies about 1 percent of the country’s power. To build enough turbines to get wind power to 20 percent would cost at least $1 trillion over the next twenty years (one expert puts the cost at $14 trillion). Not only would the federal government have to provide significant tax breaks to the builders of wind farms to make them economically viable compared with the cost of producing fossil fuels, but it would also have to fund a nationwide network of transmission lines to get the power from the Wind Belt to the East and West coasts. The price tag? An estimated $70 billion. And there’s always this question: What would happen to our nation’s power grid on one of those days when the wind does not blow?

Furthermore, powering vehicles with compressed or liquefied natural gas, which has been a pet project of Boone’s since the late eighties, has been slow to catch on. For one thing, few passenger cars are being built by U.S. automakers for natural gas use. And while inexpensive equipment has been created that would allow the owners of natural gas cars to fill up at home, plugging into their own natural gas lines, they’re still limited by where they can drive because there are only a handful of natural gas filling stations around the country.

When I threw these various criticisms at Boone, he just shrugged. He said the cost for tax breaks for wind farms is minimal, given that we spend $700 billion a year on foreign oil. He also said that as long as other domestic energy sources are being developed, including solar and nuclear power, the nation would have plenty of energy for those days when the wind was not blowing. As for the natural gas part of his plan, he argued that if Congress simply provides modest tax breaks for fuel retailers to invest in natural gas pumps at their stations and for automakers to build more natural gas cars, consumers will readily give up their gas-guzzling automobiles. “Do you realize that if you could fill up your natural gas car at your home right now, it would cost you only $1.50 a gallon?” Boone told me. “Who’s going to walk away from that?”

Since the rollout of Boone’s advertising campaign, the presidential candidates have been talking more about energy. Perhaps coincidentally—or perhaps not—McCain quoted Boone almost word for word in late July when he told one audience about the outrage of America’s spending $700 billion a year on foreign oil. Obama mentioned Boone by name in early August, when he told an audience in Michigan, “Even Texas oilman Boone Pickens has said . . . ‘This is one emergency we can’t drill our way out of.’”

When the advertising campaign ends later this fall, Boone plans to spend more of his millions on a major lobbying effort to get these various tax incentives passed in Washington—“hopefully within ten days after the new president is sworn in,” he said.

“Are you kidding?” I asked, incredulous. “Ten days?”

“Man, I’ve got to move fast,” he said. “I’m headed into my ninth decade. At my age, I don’t have time to plant small trees.”

Although Boone likes to tell people that a doctor told him he has the arteries of a 54-year-old—“He says the good news is that I could live to be 114,” he often jokes, “but the bad news is that I won’t be able to see or hear”—he knows there’s a chance he won’t be alive to see his Pickens Plan come to fruition. “You can tell he senses the compression of time,” said Stillwell. “It’s not that he’s afraid of the idea of death. He’s challenged by it. He wants to get more accomplished before his time comes than anyone can imagine.”

Indeed, everyone who knows him says he’s working harder now than he ever did during his takeover years. Madeleine told me that Boone refuses to take any kind of vacation except for weekends to the ranch or to her California home. “And even then he’s always on the phone. Once, I suggested that we go on an African safari. He said, ‘Honey, let’s go down to the zoo to see some animals, and we can be done in an hour.’” He did take a two-week trip to China to look at business prospects. “I swear, within seventeen hours, he was asking me when we could head back,” said Rosser, his public relations chief.

Boone certainly doesn’t plan on checking out anytime soon. When Rosser suggested they name his new book “Life in the Fourth Quarter,” Boone snapped, “I’m not in any fourth quarter.” He also just put his name down on the waiting list to get the newest Gulfstream G660 jet, despite being told the wait will be about ten years. And one night while I was having dinner with Boone, Madeleine, and some of his associates at a restaurant in New York (everyone ordered steak except for Madeleine, who was eating what looked like a head of lettuce), a man leaned over and told me that if the Ford Motor Company ever goes bankrupt, as was being rumored that very week on Wall Street, he was going to try to persuade Boone to buy the automaker and turn all its cars into natural gas-powered vehicles. “I think he’d do it,” the man said. “Boone always loves a challenge.”

Boone hadn’t been able to hear everything the man said, but he did hear the word “challenge.”

“What’s that?” he said. “I like a challenge?” He looked around the table. “Now, that’s the damn truth.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Energy

- Longreads

- T Boone Pickens