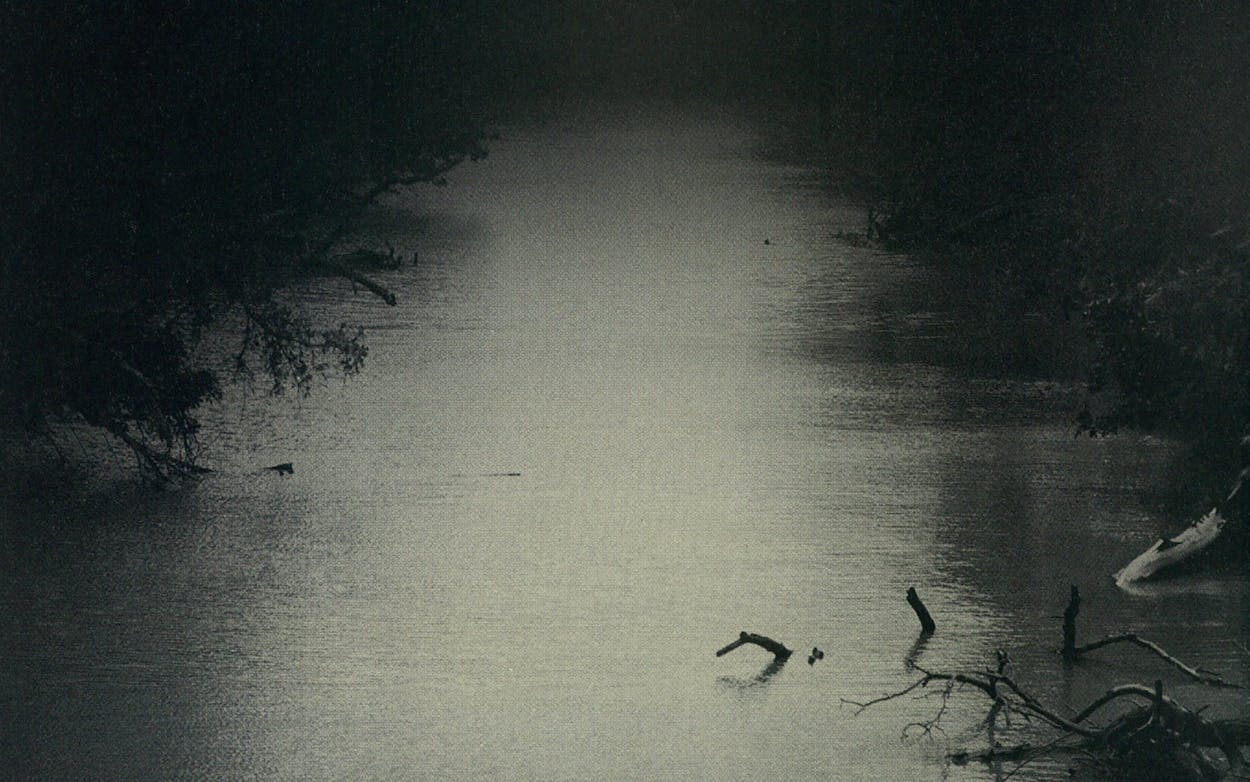

Had a hard rain fallen, she might have drifted out to the Red River and never been found. But just before dusk on a fall day six years ago, in the rough clay bottomland on the Texas side, a rancher driving down a dirt road with his seven-year-old granddaughter stopped his pickup at a backwater creek. The little girl spotted the body first, pointing to a muddy spot near banks overgrown with greenbrier vines. The rancher squinted—he had left his glasses back home—and decided he was looking at a drowned calf that had washed downstream. “There’s a body in the water,” his granddaughter said, even after they returned home. On his morning rounds the next day, the rancher drove out to the Belknap Creek bridge. The pale, ethereal object had glided closer, and he could see now that it was indeed a girl, her sandy-colored hair fanning out along the murky surface of the water. Within hours, local lawmen had identified her as Heather Rich, a high school sophomore from Waurika, Oklahoma, a small town just across the Red River. Her face was unrecognizable because she had been shot in the back of the head. She could be identified only by her gold signet ring, heart-shaped and inset with a diamond, which had been a present for her sixteenth birthday.

Everyone in Waurika, a town of 1,988 people, knew Heather Rich. A slight, pretty girl with blue-gray eyes, she was vivacious and laughed easily and enjoyed the attention of boys—something her three brothers, all football players, tried hard to shield her from. “Heather was beautiful; pictures don’t capture just how pretty she was,” says Pat Harmon, of Pat’s Beauty Shop in Waurika. “People adored her because she was always so bubbly and made a point of being nice to everyone.” Voted sophomore-class favorite, Heather was a Waurika Eagles cheerleader—the girl who smiled while teetering at the top of the human pyramid—and she was nominated for homecoming queen just days before she disappeared. A diligent student, she also made the honor roll. But in the weeks before her murder, she had been acting strangely. She was suspended from school for being drunk while leading cheers at a football game, and around the house, she had become moody and withdrawn. A close friend would later tell the FBI that, despite her ebullient public persona, Heather was a “very troubled girl.” All anyone knew for sure was that she had slipped out of her bedroom window on a school night, just after eleven o’clock, and hadn’t come home.

Rumors flourished in the days following her disappearance. People had last seen Heather walking along the highway trying to hitch a ride, they said, or sitting in a pickup with two boys or placing a call from a phone booth on the outskirts of town. She was silenced, went one story, because a local teenager’s suspicious death, ruled a suicide, had in fact been a homicide that she had witnessed. Another had Heather falling victim to foul play after dancing in a strip club or, alternately, running around with a group of local methamphetamine dealers, who killed her at a cotton gin. Every town has a story onto which it projects its fears, and in Waurika the story of Heather’s murder was embroidered with each telling. Her family suspected that her killer was not a stranger. “We had her funeral out of town, in Comanche, and we wouldn’t let anyone touch the casket because I promised Heather that whoever did this to her would never touch her again,” says her mother, Gail. As the rumors multiplied and grew more fantastic, no one could fathom who would want to hurt Heather Rich.

Heather Rich’s murder outraged the inhabitants of Red River country, not once but twice—first, when she was killed, in 1996, and again this past winter, when her killers slipped from the Montague County jail, northwest of Fort Worth, and headed for the river. Newspaper accounts of the escape focused on the manhunt, paying scant attention to the original crime or the victim, invariably described as a “sixteen-year-old Waurika, Okla., cheerleader.” Only along the river did people know what the crime had done to their isolated slice of the world, the illusions it had cruelly stripped away.

Waurika lies on what was once the Chisholm Trail, now U.S. 81, a long, lonely stretch of blacktop that threads north from Fort Worth through a succession of fading cattle towns into Oklahoma. Here, an abrupt bend in the river slows its waters enough to allow for crossings, but the river is mercurial: Just a few miles from Belknap Creek is a cemetery lined with rough-hewn sandstone markers, the makeshift graves for cowboys who drowned fording the river more than a century ago. The river can be a place of sudden violence—a mean, mud-red waterway whose banks are thick with quicksand and diamondbacks and old Comanche arrowheads—and so can the land around it. Years ago, the rancher who found Heather Rich’s body unearthed an old nickel-plated .45-70 rifle while he was plowing his pasture. “That’s a cavalryman’s gun,” he explains. “It’s anyone’s guess why it was buried three feet deep, but its owner was probably buried along with it.” As brutal as this corner of Texas has always been, north of the Red River has always been wilder. Sheriffs were scarce in Indian Territory, as Oklahoma was still known at the turn of the past century, and Waurika was no exception. “People came here to escape the law,” says Nancy Way, the town historian.

By the time the Riches moved there from nearby Lawton, in 1974, after one of their neighbors was raped, Waurika was a quieter, blander place, content to forget its history. Duane and Gail Rich had hoped the town would insulate their children from the hardness of the world. Waurika seemed peaceful and safe, the sort of place where kids couldn’t get into too much trouble because there wasn’t much trouble to get into. With no stoplights and few temptations, it reminded them of the tiny town of Elgin, Oklahoma, where they had grown up and met as teenagers. Gail was fourteen when, at a Future Farmers of America auction, she asked her father to bid on Duane—a sturdy farm boy who was offering a day’s labor—in hopes she might catch his eye. Their first date was to a prison rodeo, and they married when Gail was seventeen. She was offered a full music scholarship to the University of Oklahoma, but Duane wanted her to stay home, so she poured her energies into teaching Sunday school and playing piano at their church instead. In the summers she sang in local revivals, while her children—three boys and Heather, the third-born—napped in the pews. “Heather was a naive girl with a big heart,” says Gail, now 47, with a faint smile. “Blond all the way to the roots.”

If Waurika seemed to Gail and Duane an idyllic rural town, it had an entirely different effect on Heather. Waurika has no movie theater, no park, no rec center, no cafes open late; the nearest fast-food place then was in Comanche, seventeen miles away. “Heather always wanted to break the monotony,” says ex-boyfriend Randy Wood. “She was always restless. She hated being bored.” Some nights she would slip out her bedroom window to smoke a cigarette in the dark; other nights she would catch a ride and cruise Main Street, the three-block-long strip where teenagers line up their pickups and talk about the night’s possibilities. The only reliable entertainment in town, remembers Randy, was “getting drunk and partying.” Heather and her friends would drive the back roads to Lake Waurika or out to remote pastures where they could build bonfires and drink and smoke pot. What was passed around as often as marijuana on those country nights was methamphetamine, a homemade form of speed that causes a heart-pounding euphoria. Heather didn’t smoke meth at first; Randy did. He was the captain of the football team and a popular senior, a ruddy, broad-shouldered boy who was universally liked. But underneath the bulky uniform, he was another lost kid.

Heather thrived on male attention and knew how to garner it. “If you’ve got it, flaunt it,” she liked to say. “She had no idea the power she had over men,” says Gail, who had watched men her age flirt with her daughter. “She assumed everyone had the best of intentions.” The Riches forbade Heather to date until she was sixteen, and after that, she had to double-date with her brother Stephen and his girlfriend—a circumstance Heather found mortifying. “I’ll be an old maid,” she used to moan. “I’m already the last girl in school who’s still a virgin.” In a heart-shaped box, she stashed the pieces of gum she was chewing when boys had kissed her, with a list of the boys’ names: proof to herself, perhaps, of her own romantic and sexual worth. She spent hours holed up in her bedroom—a pink-and-white sanctuary with porcelain dolls and a dressing table arrayed with makeup—primping and appraising her flaws in the mirror. She was meticulous about her appearance, tweezing her eyebrows into precise half-moons and sometimes washing her hair two or three times a day, until she had styled it just right. Her perfectionism took a dark turn starting in the summer before the eighth grade, when she began vomiting to control her weight. Boys liked her figure, and she was determined to stay a size 2.

Randy resented Heather’s flirtations with other boys. His own teenage uncertainty was heightened by his hard-luck background. His family was one of the poorest in town; he had never known his father, and his mother had a history of drug use. He had started smoking pot in the third grade after stealing it from his mother, and he often had the glassy-eyed look of a kid in a world of his own. Still, as a Waurika Eagles running back, he had earned the respect of his team, and around town, people liked the soft-spoken, well-mannered teenager who was making the best of the bad hand life had dealt him. His family’s poverty was evident from their run-down frame house, where broken windows were covered up with old quilts and cardboard, but Randy tried to present himself well, wearing oxford shirts and khakis and holding his head up when he walked the mile to school. Randy was just a “big, dumb kid” back then, people say, “a little slow” but adored around town. “Heather befriended the underdogs—that’s why she liked Randy,” says Gail. “She felt sorry for him. She took him to church. She felt like Randy had never been given a chance.” His five-month relationship with Heather was intimate but not one of great passion; they would never sleep together. The relationship was so low-key that many people, including the Riches, mistook them for friends. Heather and Randy liked to sit and talk for hours on end—but even after so much time together, Heather could seem like a stranger. “I knew her but not like I wanted to,” Randy says, “not like I should have.”

Heather was also growing more distant from her parents, who were consumed by a family crisis. Duane, an electrician, had nearly been killed on the job when a transformer blew up, burning him over 65 percent of his body. His injuries changed him from an involved father and husband into a helpless patient: Skin grafts and physical therapy would follow, and he had to learn to walk again. Heather fed him and dressed his wounds, and when her mother began working long hours to make ends meet, the cooking and cleaning duties fell largely to her. “Our lives were in chaos,” says Gail. “I didn’t give Heather the time she needed. I should’ve checked up on her friends instead of taking her word. She’d say, ’But, Momma, there’s good in everybody’ and look at me with those big blue eyes.” Mother and daughter were close, though Gail didn’t know the extent of her daughter’s self-destruction: Heather had begun to cut herself now and then, running a razor blade across her legs until she drew blood.

A few weeks after school started, Randy broke up with Heather after hearing a rumor that she had gone skinny-dipping at a co-ed pool party. Within a week, an acquaintance of theirs named Dennis Wayne Goss, a twenty-year-old from the nearby town of Terral, fatally shot himself in the head. Deeply rattled by the breakup and perhaps Goss’ suicide, Heather’s behavior grew more erratic. “She had a brightness, a glitteryness, about her eyes,” says Gail. She would later learn that Heather had started experimenting with meth not long after Randy stopped seeing her.

Toward the end of September, six days before she disappeared, she was drunk on the sidelines at a football game. She was suspended from school for three days while administrators decided whether to kick her off the cheerleading squad. The Riches became so concerned about Heather that they made an appointment with a therapist for the following Thursday, October 3, 1996. “We wanted to get her help and figure out why she wanted to hurt herself,” says Gail.

On October 2 Gail came home to find a $300 long-distance phone bill that Heather had racked up calling friends from church camp—a bill the family could not pay. Angry and exhausted from the strain of working sixteen-hour days, Gail lost her temper. “All you ever do is cost me money,” she snapped. Wounded, Heather retreated to her room. She came to her parents’ bedroom later that evening and wished Duane good-night, telling him she loved him. She ignored her mother, walking past her without meeting her glance. Gail never saw her daughter again.

The next morning, the Riches went to the Jefferson County Sheriff’s Department to report Heather missing. Sheriff’s deputies refused to take the disappearance seriously, assuring Gail that Heather had probably just run away for a few hours to give her a scare and advising her to return home. “When your daughter’s missing, you can sit at home,” Gail said angrily. She knew her daughter hadn’t run away; Heather’s makeup bag, which she never left behind, was still in her bedroom. None of her clothes were missing, and her diary lay open on her bed. As Gail made frantic inquiries around town that morning—”I was beating on people’s doors,” she says. “I was working on pure adrenaline and anger”—a friend at Waurika High School slipped her the day’s absentee list, which included Randy Wood. Gail reached him by phone and asked if he had seen Heather. Randy said he hadn’t, then added, “I was with Josh Bagwell all night, till six this morning.” His voice sounded tired and flat. When Gail pressed him, he repeated that he hadn’t seen Heather; he was with Josh Bagwell all night. “Randy, if you knew anything that could help us find Heather, you would tell us, right?” Gail asked him. “Yes, ma’am,” he replied. When she hung up, she added Josh Bagwell to her list of people to question.

Randy and Josh were good friends, though they made a curious pair. Josh was a snob, say some who knew him—a clean-cut, pampered seventeen-year-old who lived with his wealthy grandparents, Toad and Hattie Dale Anderson. “The Andersons were always a little bit better than everybody else,” says one local. “They’re showy with their money. They have a big house, the newest cars. For Waurika, they’re high rollers.” Josh’s mother was divorced and lived out of town; at sixteen, he moved in with his maternal grandparents, who liked to indulge him. With little discipline at home, he bristled at authority. When he was arrested once for drunk driving, he scuffled with police officers, yelling, “I want my f—ing attorney,” and was charged with resisting arrest. His white Dodge Stealth was the fanciest car that any teenager had in town, and Randy was awed by his easy wealth. “Josh told me it was his sixth brand-new car,” says Randy. “He said he’d wrecked some of the others.” Heather was taken with Josh’s life of privilege too. Her ongoing flirtation with him had paid off that September, when Josh promised she could ride on the back of his car in the homecoming parade.

The day of Heather’s disappearance, Josh was also absent from school. He had been suspended for three days for cutting class; earlier that week, he had attended his friend Dennis Wayne Goss’s funeral. When members of the Rich family questioned Josh, as they did dozens of teenagers around town that day, he shrugged and said he hadn’t seen Heather in a week.

As days went by with no sign of their daughter, the Riches’ desperation led them to hire a private detective and to use a friend’s bloodhounds to sniff around wooded areas near town. Many tips that came in about Heather’s whereabouts circled back to something Gail had not previously known existed: Waurika’s drug culture. “We discovered that there were several meth labs in town and houses where people dealt drugs on nearly every block,” Gail says. “Duane and I had raised four kids in Waurika, and we had no idea this was going on. Our kids, everyone’s kids, knew about it. After the sun went down, our town was full of dope.”

On the eighth day of the Riches’ search, a rancher reported finding a body. The victim’s identity was soon confirmed. “Duane walked in the door and I took one look at him and I knew she was dead,” Gail says. “I said, ’Just tell me. Say it real fast and get it over with.’ He told me that someone had shot her and thrown her in the water and that she was never coming home. I remember screaming and beating on him for an hour, saying, ’No, no, no.’” Word filtered through Waurika the next day. “There was shock and total disbelief,” remembers Mayor Biff Eck. “No one could understand how something like this could happen to someone from our town.” Randy was at school, standing at a water fountain, when he heard the news that Heather’s body had been found. “It was like time stopped,” he says. That night he was crowned Waurika High School’s homecoming king. During the halftime ceremony, he looked haunted under the glare of the stadium lights.

A team of twenty investigators interviewed more than one hundred people in the days to come, with little luck. “Nobody wanted to talk,” says Montague County sheriff Chris Hamilton, one of the Texas investigators working the case. “There was a party culture up there, and kids didn’t want to snitch. There was a code of honor, an us-against-the-police kind of attitude.” Even the Waurika newspaper, the News-Democrat, observed that local teenagers were adhering “to a code of silence that would make the Mafia proud.”

The Riches often stopped by the investigation’s makeshift command post—the old redbrick train depot, newly wired with laptops and phone lines—to offer home cooking and words of thanks. But as days, and then a week, passed with no progress, a sense of unease settled in. One of the few credible leads was that Heather had sneaked out to go to a party at Josh Bagwell’s house the night she vanished. Randy Wood had told Gail earlier that he had been there until six in the morning. They hadn’t seen Heather, Josh said. Only two people had stopped by his house that night: Randy and Curtis Gambill, Josh’s drinking buddy.

Curtis Gambill lived with his grandmother Reda Robbins, in Terral, twenty miles downriver from Waurika. At 64, Reda had spent her whole life on the river, and she knew it well: At dusk, she could stare up at the sky and then out at the river and tell whether its water would run red the next day or gin-clear. She knew where the imprints of wagon wheels were still worn deep in the sandstone lining its banks and where, among the wild lilac and blackthorn and yucca, gold was rumored to be buried. Reda has both Cherokee and Choctaw blood in her; her high cheekbones are set against jet-black hair and wide, expressive blue eyes that catch the sunlight, and she is eccentric in the way that all people deeply connected to this river are. She has had a series of husbands, and for years she sang in a local country and western band, crooning lonesome love songs. As a girl living on the river’s Texas side, she spent countless afternoons fishing on Belknap Creek. Back then, she used to walk the five miles from her house, down a dead-end dirt road, and sit on the Belknap Creek bridge, baiting hooks with earthworms and lowering them down below. Years later, she liked to take Curtis fishing there too.

Reda was disturbed by the news of Heather’s death, not only because it happened in her most beloved, and secret, corner of the river bottom, but also because she intimately knew the anguish of murder. Her mother was one of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas’ first victims; in 1982 he stabbed her in the heart and shoved her in a wood-burning stove in Ringgold, only a few miles from Belknap Creek. In the years that followed, Reda had worried about her grandson, Curtis. He had taken an unloaded gun to school and was sent to a juvenile facility as a result; after that, he got mixed up in drugs. “Curtis had a mean streak,” says one local. “He was always raising Cain, and everyone knew to steer clear of him.” A river rat, Curtis was tan and straw-haired, with green eyes that assessed whatever stood in his way with a cold, hard stare. He liked to camp and fish and roam the bottomland, and Reda spent a great deal of her time worrying about him. She knew he had been brooding ever since his best friend, Dennis Wayne Goss, had committed suicide. Curtis had made some strange remarks to her about his late friend: Dennis Wayne hadn’t killed himself; he had been murdered, and Curtis intended to find out who did it.

Reda watched her grandson as she made supper on the day Heather’s body was found, wondering what he knew. He was sitting on the back porch, playing her old guitar.

“They found that missing girl from Waurika,” Reda called out from the kitchen, through the screen door. “They found her floating in Belknap Creek.” Curtis stopped strumming the guitar and fell silent. Reda began to say more, but he cut her off.

“Grandma,” he said, his voice ice-cold. “I don’t give a f— about that little girl.”

Texas Ranger Lane Akin arrived at Belknap Creek on the afternoon of October 10, 1996, when Heather was still floating among the reeds. After crime scene photos were taken, the lawman waded into the creek with Sheriff Hamilton and gently carried her to dry land. Her body was so badly damaged that the Riches were never allowed to see her; the autopsy photos would later make jurors recoil. She had been shot nine times—once in the head, eight times in the back—not with a pistol but a shotgun. All the Riches had left of their daughter was her ring. As the murder investigation got under way, Gail was reassured by the presence of the Texas Ranger. Akin’s calm, deliberate style had served him well in the past, when criminals had felt so at ease around him that they had sometimes divulged the details of their crimes. But while he had worked dozens of murder cases before, this case would take a greater emotional toll—something his fellow investigators noticed from the moment he carried Heather’s body from the creek. Akin’s only daughter was then a high school cheerleader, an outgoing fifteen-year-old girl in the North Texas town of Decatur whom he had done his share of worrying about. “This one hit real close to home,” Akin says.

Each night, as he drove back to Texas, he wondered what he was overlooking. “It was very hard to leave at the end of the day, knowing we weren’t any closer to making an arrest,” he says. The investigation had initially focused on a red herring: a meth dealer Heather may have known who turned out to have an alibi. Akin now began to look more closely at the party Josh had thrown the night of Heather’s disappearance.

Josh, Curtis, and Randy all claimed they had played dominoes and drunk whiskey in the “party trailer” behind Josh’s house that night, and they all insisted they hadn’t seen Heather. Akin was skeptical. As the investigation plodded along, Randy often sat on his porch, holding his head in his hands. He drank heavily, and he stayed high most of the time. In a newspaper profile of the new homecoming king, he seemed gloomy and remote. He shrugged off several questions, listing his favorite color as black, and when asked for “words of wisdom for underclassmen,” he answered cryptically, “Cruise the back roads.” Was he grieving or, as Akin suspected, did he know more than he was saying?

With Paul Smith of the Montague County district attorney’s office, his partner for the investigation, Akin decided to stop by football practice one afternoon and pay Randy a visit. When Randy walked off the field and saw the two lawmen waiting for him, his face froze. “Lane and I looked at each other,” says Smith, “and we knew for sure Randy was involved in Heather’s murder.”

Randy stuck to his story, though Akin made note of the flat, detached way that he described the evening. “He had rehearsed that story again and again,” Akin says. “Telling it kept him from showing any emotion.” The next morning, Akin got the break he needed. A local sheriff’s deputy discovered that Josh had bought four boxes of shotgun shells at Beaver Hardware a few days before Heather’s murder: Winchester double-aught buckshot, the ammunition that a firearms expert had determined was the kind used by Heather’s killer. The owner of Beaver Hardware also identified Curtis Gambill from a photo lineup; he had accompanied Josh to the store. Paul Smith had investigated the brutal murder of Curtis’ great-grandmother by Henry Lee Lucas years earlier, and he knew the family well. He suggested to Akin that they visit Reda Robbins. Reda had not been forthcoming with investigators until then, but when she saw the detective who had helped find her mother’s killer, she agreed to talk. During the course of their conversation, Reda mentioned that Curtis had had a shotgun but that he’d said he had gotten rid of it. “Old Blackie” was a Mossberg twelve-gauge shotgun: the firearm that investigators would determine was the murder weapon.

Only later would it come to light that Curtis Gambill had once bragged about his “ultimate fantasy”: to kidnap a girl, rape her, and then “blow her head off.” He made the boast at the age of fifteen in a juvenile detention center, where he was being held after threatening to kill several teachers. He was a volatile kid with a long criminal record. He was rumored to have shot other people’s livestock for sport, and he had broken out of every juvenile facility that held him. He ran with a rough crowd of meth users, including the late Dennis Wayne Goss, and in school he terrorized other kids, making boys fight each other by threatening that otherwise they would have to fight him. At seventeen he was briefly committed to a psychiatric hospital. “Curtis Gambill is the most violent person I’ve ever known,” Akin says now. “When you’re around him, you literally feel like you’re in the presence of evil.” Both misfits, Curtis and Josh found solace in drinking and hanging out along the river—often camping and fishing together—and they shared a love of guns. Randy was the odd man out, having met Curtis only briefly when they worked one summer in the watermelon fields. What brought them all together the night of Heather’s murder had its own simple logic: Josh had a bottle of whiskey.

The story would unravel the following day, when Curtis broke under Akin’s questioning. “Gambill knew he was in a bind, so he told us a story that made Randy Wood out to be the killer,” says Akin. “He was extremely cooperative and seemed to be enjoying the attention.” Between bites of tacos, Curtis cavalierly offered up the details. “I didn’t know her,” he began, while Akin typed. “She snuck out. Her and Josh had a date.” Curtis explained that he and Randy had left the trailer to give them some time alone. While they were gone, Josh got Heather drunk. “Josh had sex with her for a couple of hours,” he said. “When me and Woody, Randy Wood, got back, she was hammered. She was kissing on us. Me and Woody was going to get a piece, but she passed out.” The boys drank more. “When she woke up, she was crying and screaming. Then she passed back out. Josh started freaking out. . . . Josh said he didn’t want to go down for it, raping Heather.” Randy was anxious about rape charges too, Curtis said, because Randy had tried to have sex with Heather. So Randy carried her, still unconscious, to Josh’s pickup, and they all drove to the Belknap Creek bridge. “Woody shot her,” Curtis claimed. “Woody said, ’Throw her ass over.’ All of us grabbed her and threw her over in the creek.”

Akin had heard a lot in his twenty years in law enforcement, but as he slid the typed confession across the desk for Curtis to sign, he felt sick. Heather’s life, to these boys, had been so easily disposable. “I had to grit my teeth and go on,” Akin says. He believed most of Curtis’ story, though he sensed that Curtis had killed her: The murder weapon was his, and the crime scene was a place only he was familiar with. Akin’s hunch was confirmed when Randy told almost the same story later that night but with Curtis firing the gun. Heather had been drifting in and out of consciousness when Curtis “had sex” with her too. “I had my pants down, but I didn’t,” Randy said in a low monotone. When they arrived at the creek, they “sat Heather on the bridge and she fell over. I got back in the truck, and I just sat there with my hands covering my face, and that’s when I heard the shots. Josh and Curtis were outside. After the shots stopped, I looked up and Curtis had the shotgun.” Randy would pass a polygraph test; Curtis failed his. But why had Randy not tried to save her? “I really didn’t believe it would happen until we got to the bridge,” Randy told me. “I hoped Curtis was joking, but when we got out of the truck, he had the shotgun. He was giving orders; he was firing himself up. I let it happen. I was scared to death of him.”

While Randy was giving his statement to Sheriff Hamilton, Akin served the warrant for Josh’s arrest. In Josh’s bedroom were two swords, an SKS assault rifle with a bayonet, another assault rifle, and a book on making bombs. Though he initially refused to go with the Texas Ranger, he finally relented. As Akin drove, he tried to engage Josh in conversation.

“I’m sure you’ve had some sleepless nights since Heather’s murder,” Akin offered.

“You just woke me up,” Josh said with a sneer. “Did it look like I was having trouble sleeping?”

Six years later Akin is still galled by those words. “Josh Bagwell had participated in a crime that devastated an entire community,” Akin says. “A family would never know their daughter. Heather would never grow up, never get married, never have children of her own. And his conscience wasn’t troubled at all. He could sleep just fine.”

The son of a Church of Christ preacher, Montague County district attorney Tim Cole is an intense, unyielding adversary in the courtroom—he prefers facts to florid oratory—whose sense of moral certainty has helped him persuade juries to convict in all twelve murder trials he has prosecuted. Curtis Gambill’s capital murder case, which was the first to come to trial, presented a tactical problem: To convict Josh Bagwell of capital murder, Cole needed testimony that Josh knew of the plan to kill Heather before they reached the creek. Cole had sought the death penalty against Curtis, but during jury selection, a plea bargain was struck: Curtis would admit he shot Heather and testify against Josh if he was spared death. After much agonizing, the Riches agreed that the state should accept the deal, even though it meant forgoing the death penalty for their daughter’s killer. “They gave Curtis Gambill his life,” Cole says. Moments after Curtis pleaded guilty and was given a thirty-year sentence, he flew into a rage, grabbing the bailiff by the neck and trying to choke him. It took six men to wrestle Curtis to the ground, including Lane Akin, who leaped out of the spectator section to put him in a stranglehold. Cole watched, his face drained of color. What sort of Faustian bargain, he wondered, had they made?

Even with Curtis’ testimony, Cole harbored doubts about winning a conviction against Josh Bagwell. Josh had refused to give a statement to investigators—he was the only one of the three boys not to admit his guilt—or to take a polygraph test, and his family had hired a team of high-priced defense attorneys to secure his acquittal. The case against him rested largely on the word of Curtis and Randy, who could implicate Josh in the murder scheme but who could also compromise their credibility by pointing fingers at each other for pulling the trigger. Before the trial, Josh bragged to friends that there wasn’t enough evidence to try him. “His family’s attitude was that I was a country bumpkin who couldn’t win this case and that Josh hadn’t done anything wrong,” Cole says. “They had the arrogance to bring his sports car to the courthouse while the jury was deliberating because they were so sure the jury was going to let him off.”

From the first day of The State of Texas v. Joshua Luke Bagwell, the defense elected to put Heather’s character on trial, painting her as a promiscuous drunk. “They made her look like the Whore of Babylon,” says Jeff Hall, a former publisher of the Waurika News-Democrat. Scant was said about the boys’ own alcoholism or enthusiasm for casual sex, only Heather’s supposed transgressions. The subtext of the defense’s argument was that Josh could not have raped Heather because she was always ready and willing. Defense attorney John Zelbst went so far as to cross-examine Gail about each of her dead daughter’s failings—her smoking, her bulimia, her marijuana use: “She was your perfect child, but she wasn’t quite perfect, right?” Josh sat quietly behind the defense table, taking notes on a yellow legal pad. What the jury could not see beneath his suit were his jailhouse tattoos—among them the swastika and other white power symbols that adorned his arms. Nor did the jury know that Josh had not only tried to incite a riot on his cell block but also threatened to kill several guards and attacked a police officer. Guards also discovered a hole he had chipped through the cinder-block walls.

“We were all afraid that Josh was going to walk,” says Cole. Though Curtis had originally agreed to testify against Josh, he had welshed on his plea agreement, insisting that it was Randy, not himself, who shot Heather, and that Josh had known nothing of the murder plot. That night Cole got word of yet another setback for the prosecution: Randy, who was scheduled to testify the next day, was backing out of his plea bargain as well. Cole thought all was lost.

But Randy Wood had something else in mind. Conscience-stricken, he still wanted to testify against Josh, but he would not accept a plea bargain in return, for fear that it would taint the veracity of his testimony in the eyes of the jury. And so Randy sacrificed his future, doing what no lawman who worked this case can remember a defendant ever doing: He turned down a forty-year sentence with the possibility of parole after thirty years and testified anyway, thereby incriminating himself and subjecting himself to, at best, a mandatory life sentence for murder. At worst, he would face a death sentence. Randy’s attorney urged him to take the deal, but Randy had made up his mind. “I wanted everyone to know I was telling the truth,” Randy told me. “I owed that to Heather and her family.”

The next day, Randy testified in a low, halting voice that Josh had known full well of the plan to kill Heather: Contrary to the defense’s story, Josh was present in the trailer when the plot was hatched to shoot her. Before the shooting, he had helped carry her from the pickup to the bridge, Randy said. Afterward, he had weighed her body down with a rock and helped throw her into the creek. “I looked in Randy’s eyes, and I knew he was sincere,” says Gail. “I wanted to reach out to him, to thank him for his honesty.” Josh took the stand next, giving a convincing performance of a polite, respectful eighteen-year-old. (“He was so well prepared that I could’ve slapped him and he would have said, ’Thank you,’” Cole recalls.) Josh testified that he hadn’t known about a plan to kill Heather and that it was Randy who had killed her. Only once did Josh stray from the script, but it was a costly slip: After hearing gunshots while urinating near the bridge that night, he said, he ran back to see what had happened. Then, he testified in the present tense, as if watching the events unfold before him, “I see Curtis—or, I mean, excuse me—I see Randy lowering the gun.”

The jury found Josh guilty of capital murder, which carries an automatic life sentence, and of conspiracy to commit murder, for which the jury assessed a 99-year sentence to be served concurrently. Gail kissed Heather’s signet ring over and over as the jury read its verdict, silently rocking back and forth in her seat. In addition to his sports car, Josh’s family had taken to the courthouse dozens of balloons and presents for him—so sure had they been that he would be acquitted. Now they sat in stunned silence. “My son is no angel, but he damn sure is no murderer,” his mother, Cherese Smith, told reporters.

Before the defendant was led away, Gail was allowed to say a few words to him directly. As she began to speak, imploring him to never forget Heather or the horror of his crime, Josh’s relatives stood up and filed out of the courtroom. “By your family exiting, I see why you are the way you are,” Gail told Josh, who stared back at her blankly. “You haven’t ever had to pay for the mistakes you made. But you’re going to now. You took away the most important thing in our life.”

Randy would stand trial later that year and be found guilty of capital murder. He too must serve a mandatory life sentence and will not be eligible for parole until the year 2036, when he will be 57 years old. While Cole is deservedly proud of his victories in these trials, he is subdued when he speaks of the teenager who, late in the game, found the strength of character to own up to his crime and paid for it dearly. “I don’t feel very good about Randy Wood being in prison for the rest of his life,” says Cole. “I tried every way in the world to get him to plead guilty, but he would not take the plea. I’m sure there was some self-interest in his decision: He wanted people to know he didn’t kill Heather. But I will forever believe it’s because he has a conscience.” Cole’s opinion is shared by Gail, who speaks of Randy with a bittersweet smile and says he is redeemed in her eyes. “Heather lay in that creek for eight days and he didn’t tell me, so he must be punished,” she says. “But a lifetime is too much for Randy.”

On January 28, just before midnight, Curtis Gambill and Josh Bagwell slipped out of the Montague County jail and fled with two other inmates into the North Texas plains. The Montague Four, as they were soon known on TV news bulletins, escaped after taking a guard hostage with a homemade knife, forcing the only other guard on duty to open an outside gate. Though Curtis and Josh had been incarcerated in state prison, they had been transferred to Montague County earlier that month for Curtis to be prosecuted by Cole on charges of conspiracy to commit murder. Curtis was convicted on January 16 and given a life sentence, ensuring that he would spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of parole. When Cole learned of the escape, he was apoplectic. “You spend six years trying to make sure that these people will never hurt anyone ever again, and then in the blink of an eye, they’re gone,” says Cole. “I carried a gun for the first time in my life. They had absolutely nothing to lose.”

Curtis and Josh headed to the place they knew best, the Red River. Despite a massive manhunt with hundreds of lawmen from Texas and Oklahoma, the escapees traced their way through gullies and dry washes back to Belknap Creek, hiding in caves along the river bottom. Heather Rich’s killers went unseen for more than a week, holing up in a hunting cabin, then stealing a flatbed truck and a .22-caliber revolver from Dennis Wayne Goss’s parents’ home. Up and down the river, people loaded their guns and stayed indoors, while local law enforcement braced for a bloody shoot-out. But after nine days on the lam, Curtis and Josh found themselves surrounded by dozens of lawmen at a convenience store in Ardmore, Oklahoma, and surrendered after six hours of negotiation with the FBI. As Curtis was being led away in handcuffs, he locked eyes with Jefferson County sheriff Stan Barnes. “I’ll be seeing you again,” Curtis told him with a cocky smile. Several weeks later prison guards thwarted yet another escape when they discovered that Josh’s mother, Cherese, had slipped Curtis and Josh hacksaw blades hidden inside two Bibles. She is in jail, awaiting trial.

Sheriff Barnes has reopened the investigation into Dennis Wayne Goss’s death, which was ruled a suicide by his predecessor. “Goss was a good friend of Curtis Gambill’s, and he was shot one week before Heather,” Barnes says. “It was made to look like a suicide, but the shell casing next to him didn’t match the wadding found in his head wound. He’d told his dad he feared for his life.” Barnes believes there is a connection between the two deaths. “Heather might have known something she wasn’t supposed to about the Goss murder.” His opinion is widely shared around Waurika.

Now 23, Randy has tried hard to put distance between himself and the boy he was that night on Belknap Creek. While his co-defendants were classified as some of Texas’ most ill-behaved inmates even before the jailbreak, Randy has a spotless record. He now works on the prison garden crew, digging flower beds and pruning shrubs. “Heather is the first thing I think of in the morning and the last thing at night,” he says. “I punish myself worse than anything in this prison ever could.”

Gail and Duane divorced after the murder; the pain of memory was too great, she says. Both have moved away from Waurika and the bridge at Belknap Creek. It is still pocked with the buckshot that tore apart Heather’s body and scarred with tiny fissures that fan out along the bridge’s concrete edge. There, in faded blue spray paint, someone has scrawled the word “murderers.” The creek, a deep blue ribbon shaded by hackberry and pecan trees, is a place of unlikely beauty; when the wind blows through the switchgrass lining its banks, ruffling the surface of the water, it is hard to believe that a crime of such horror could have happened in such a serene spot.

The creek appears in Gail’s nightmares, which have haunted her from the day Heather was found dead. In the dream, Heather is lying in the creek. She is alive, and she is begging for help. She is only a few feet away in the cold water. Gail holds out her hands, grasping for her daughter. But she can’t reach her. Heather is too far away.