Since he was nineteen, Mack McCormick has pursued the answers to two questions. He is now forty-seven, and although he is much closer to the answers than he was when he was nineteen, he would be the first to agree that those two questions remain unanswered, elusive, and tantalizing enough to devote another lifetime to answering them. Yet those questions are very simple: where did blues music begin and why did it begin there?

McCormick’s interest in the blues began when he was growing up. His parents were separated and he lived part of the year in Dallas and the rest in Sandusky, Ohio. Listening to the radio in each place, he became fascinated with the regional differences in music. By his late teens, when he was living permanently in Houston, this fascination had become his main interest. He had already contributed an article to a New Orleans jazz journal named “Playback” when a street corner meeting on a winter afternoon sealed his future. He was waiting for a light to change at a corner near the old Union Station in Houston when he saw a very tall old man with an odd, elongated head, wearing layers of ragged coats and jackets and carrying a guitar. McCormick parked his car and caught up with the man a block or so away. “I’d never done anything like that,” McCormick remembers now. “I was basically a shy kid and didn’t really feel at home in Texas, but I’d been reading and hearing about street singers and wandering bluesmen, and when I saw him I was so curious it overcame my shyness.”

The meeting itself was disappointing. McCormick could understand only occasional snatches of what the man said—he had slept under a bridge the night before, he’d come into Houston on a freight, and once he’d made some records—and when the man sang, his lyrics were no more understandable than his speech and he banged away on guitar strings that were dead and far out of tune. He also played a flat metal instrument of his own devising, something rather like a kazoo, that he held in his mouth even while he sang. Still, the man’s voice was memorable, however ravaged it had been by time, and he showed a certain hard-won nobility of bearing that McCormick found almost awesome.

Eventually the man wandered away leaving McCormick excited by the encounter, and now more curious than ever who the hobo musician might have been. That was in 1949, and at that time there was not much interest in America in early jazz and blues. The old 78s and the artists who made them were lost and forgotten, and except for the Index to Jazz compiled by an eccentric scholar from New Orleans named Orin Blackstone, there were no American discographies which would give any clues to what records had been made. Europeans, however, had always found jazz and blues fascinating and given that music serious scholarly attention. To McCormick’s surprise, he discovered that the greatest collections of early American jazz records were in England, France, and Belgium. He began corresponding with these critics and collectors and was a bit bewildered at first by their replies. They weren’t sure who the man on the street corner might have been, but they asked him in return, could he tell them about Texas bluesman like Blind Lemon Jefferson, Texas Alexander, “Funny Paper” Smith, Bessie Tucker, Son Becky, and many others. Except for Blind Lemon, McCormick had never heard of them.

He began to search for bluesmen in order to satisfy not only the Europeans’ curiosity but his own; very quickly those two questions about the origins of the blues began to nag him. During his search for their answers, he has become one of the most prominent folklorists in the country (despite his lack of academic degrees), a consultant to the Smithsonian Institution, the author of numerous articles, a tireless field researcher who has studied folk ways and folk music in over 800 counties across the country, and the producer of a handful of records which are among the most important of their kind ever to come out of Texas. And—finally—he discovered the name of the hobo musician who had first inspired him on that Houston street corner.

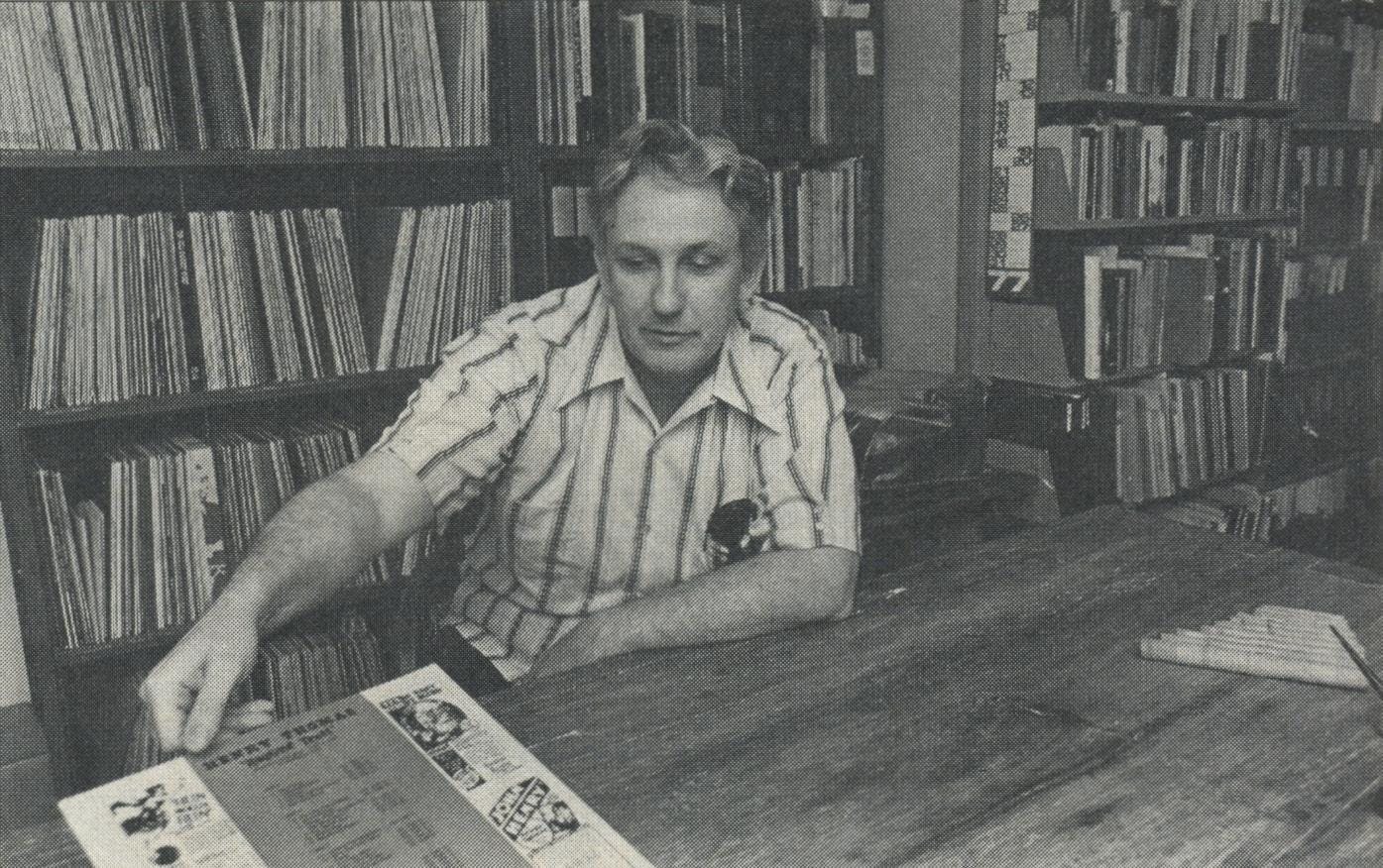

Although McCormick has spent much of his life searching out small dives, honky-tonks, and backwoods roadhouses where he could hear raw, authentic, original blues, he does less of that now. Instead he spends most of his time on what will be the culmination of his career: a definitive, two-volume study called The Texas Blues. He works in a large office in the front room of the ranch-style house in northwest Houston that he shares with his wife and young daughter. Around him are his tools: shelves of record albums and tapes, more shelves of books, music periodicals, and scholarly journals, and a wall of stereos, tape decks and recorders. Immediately to the right of his desk, taped to the side of a gray filing cabinet, is a map of the United States marked with blocks of red that he ponders from time to time. The blocks represent the black population throughout the country in 1910. “The common assumption,” he says, staring at the map, “is to think that blues music originated in areas with large black populations, but that’s not necessarily true. When I started researching in Texas, I was amazed to discover that sometimes there would be a number of singers from a certain area, say three or four in each county in a four county area and then I would go for twenty or thirty counties with the same or greater black population and there wouldn’t be a single musician to speak of. Now, take the whole southeast coast”—it was virtually a solid red on the map, a far greater density than anywhere else—“with all that population they didn’t produce much of anything in the way of blues.” He leaned closer to the map. “There’s only three important places, really. Atlanta and the area immediately around it, the Mississippi Delta and Jackson, Mississippi, and the country between San Antonio, Houston, and Dallas, including Houston and Dallas themselves. I know that’s a fairly large amount of territory, but somewhere in those three areas is where the blues began.”

The claim McCormick makes for Texas’ place in the history of the blues is based not only on the long acceptance of Dallas’ Blind Lemon Jefferson and Caddo Lake’s Leadbelly as masters of the form but also on the great number of other performers he discovered in his researches, two of whom are fully the equal of Leadbelly and Blind Lemon. Houston’s Lightning Hopkins is now well known, but, except for some early and little heard recordings, he was virtually forgotten until McCormick began to record him again in 1959. Those records, Autobiography in Blues and Country Blues, reestablished Lightning’s reputation; since then he has performed and traveled widely. Lightning is a notoriously lazy performer, especially for white audiences. Most of his recordings reflect that laziness. But McCormick pressed Lightning during recording sessions and even a casual listener can soon distinguish between the fine performances Lightning gave McCormick and the ones he gave on other records.

The second major singer McCormick discovered had previously lived a life of total obscurity. Mance Lipscomb was a sharecropper living near Navasota who had been singing and playing in the area for about sixty years. He was a great blues artist who made several records before he died in 1976. On his first album, Mance Lipscomb: Texas Sharecropper and Songster, McCormick was the producer.

Although the Hopkins and Lipscomb records have had a national popularity as well as a local one, McCormick has not had suck luck with other records he has produced. A Treasury of Field Recordings, Volumes I and II, both collections of singers in and around Houston made between 1951 and 1960, are unavailable in the United States. They are records of more interest to scholars than to the general listener, but they have nevertheless been steady sellers in Europe since they were first issued seventeen years ago. Another record, Robert Shaw: Texas Barrelhouse Piano, which has not sold especially well either here or in Europe, is nevertheless close to McCormick’s heart since it was his best example of how a whole tradition can spring up from one small area.

In his later years Shaw became a successful barbecue and grocery store owner in Austin and was named the state’s most outstanding black businessman in 1962. But in his early years he was a boogie-woogie piano player. By the time McCormick recorded him in 1963, Shaw was the last remaining practitioner of a style critics call “fast western piano.” In the twenties and thirties the fast western style could be heard in roadhouses all over Texas. There were common elements in everyone’s playing—a choppy, pounding bass, for example—but there were distinctions within the style that would inform the practiced ear whether the player had learned to play in Waco, Dallas, or wherever. Shaw came from Houston and his style was not only a Houston style but a specifically Fourth Ward style, one similar to but distinct from the Fifth Ward style. Through dogged interviews, research, and a little luck, McCormick was able to piece together how this style began. In the early 1900’s an Italian grocer named Pisanti put an old piano on the porch in front of his store. This was not especially unusual since, contrary to now, grocers used to like people hanging around and a piano was an easy way to attract hangers. An old piano player named Peg Leg Will, formerly of New Orleans, where he was Jelly Roll Morton’s contemporary, lived near Pisanti’s and would come down to the store to play the piano. His playing could be heard up and down the street, attracting a group of kids who would take over the piano when Peg Leg Will left. Their imitation soon gave way to embellishments of their own, embellishments which became in time the basis of the Fourth Ward style.

“That’s how one cultural tradition began,” McCormick says. “The blues probably began in a similar way, but where or when or exactly how is anybody’s guess.” One problem in trying to trace the blues’ evolution is that it is very difficult to know what blues singing sounded like in the years before the earliest known recordings. McCormick has unearthed the diary of a San Marcos music teacher containing lyrics he heard Negroes in the area singing. The diary dates back to 1875 and the lyrics are clearly blues. “I don’t think anyone else has found any blues that early,” McCormick goes on, “and from that evidence you might be tempted to claim Texas as the home of the blues. Well, it might be, or it might be that Georgia and Mississippi haven’t had as much research. You’ve got to be careful before making a lot of claims.” But, still, how did that music sound?

The best evidence now available is on a recent record, edited and annotated by McCormick, that is a reissue of the 23 known recordings of an old blues singer named “Ragtime Texas” Henry Thomas. Thomas is, or was, one of the most obscure figures in the history of blues. His records had a modest popularity in their day—Orin Blackstone listed six of them in the fourth volume of his Index to Jazz. Three or four of his songs have been previously reissued in folk or blues anthologies. Bob Dylan used the title of one of Thomas’ recordings, “Honey, Won’t You Allow Me One More Chance?” for a song on one of his early albums and Canned Heat’s hit of a few years back, “Goin’ Up Country,” is a note-for-note remake—with different lyrics—of Thomas’ “Bull Doze Blues.” No one knew who Thomas was, what happened to him, or where he came from except, judging by his nickname, it was probably Texas.

McCormick set out to see if he couldn’t fill in the facts of Thomas’ life for use in The Texas Blues. One of his songs, “Railroadin’ Some,” includes a list of the towns along the route of the Texas & Pacific Railroad from Fort Worth to Texarkana, so McCormick began looking for information about Thomas in that part of the state. In another song Thomas speaks a few lines, a chance occurrence which provided another clue. When McCormick played the spoken lines for older Negroes, they consistently identified the accent as one that came from the northeast corner of Texas. By asking people in that area if they remembered anyone named Thomas who was a singer, and by contacting nearly everyone there whose name was Thomas, McCormick eventually turned up a man, then living in a housing project in East Dallas, who was Henry Thomas’ second cousin. That family’s Bible revealed that Henry Thomas had been born in 1874 on a farm in Upshur county near Big Sandy. He had left home when he was very young and all his relatives could remember now was that when he returned home for a visit it was only to brag about all the places he’d been since he left. McCormick also tracked down old railroad men who had worked on the Texas & Pacific, several of whom remembered Thomas as an extremely tall man who would ride the train playing songs for the passengers as his ticket. “He was a hobo,” one man said. “I’d let him on the train unless he was too dirty.”

The research required an immense amount of time and energy, more than it might appear that a man like Thomas could justify. But there were two unique aspects of Thomas that kept McCormick on his trail. First, since Thomas would have been between 53 and 56 when he made his recordings in the late 1920s, he is probably the earliest-born bluesman ever recorded. His songs, in all probability learned during his formative years in the 1880’s and 90’s, are the best examples we have of that early blues music: blues, if not in its infancy, at least during early adolescence. And what completely appealing and satisfying music it is. Thomas’ powerful voice is both wise and benign, his guitar playing infections; and, alone among recorded bluesmen, Thomas also accompanies himself on a homemade instrument of reed pipes which were known as quills. They add a lyrical and melodic tone to his songs that supports Albert Murray’s contention in his recent Stomping the Blues, that the blues, sad as the lyrics might be, is really good-time music at the core.

The second reason McCormick pursued information about Thomas was more personal. Thomas’ records proved popular enough at the time they were released that Vocalion Records placed ads in several national and regional black newspapers. One of theses ads had a small pen-and-ink drawing of Thomas and two others had even smaller photographs. The photographs are indistinct but, like the drawing, they show one thing very clearly: Henry Thomas had an unusually long, narrow head, almost as if it had been stretched out by someone pulling on the top of his skull. When McCormick first saw the ads he was immediately struck by what he saw. The head in the photographs was the same odd and distinctive shape as that of the man he’d met near Houston’s Union Station back in 1949. The more McCormick learned about Thomas—his great height, his hobo life, his constant connection with trains—the more he became convinced that his feeling was right: the man on the street corner had been Henry Thomas.

“There’s no way to prove it, of course,” McCormick says now, “and in a way it doesn’t really matter. Henry Thomas had to have been pretty much like the man I met. But I’m certain in my own mind it was Henry Thomas. It may not be the best scholarship to think so, but then scholarship isn’t everything, is it?”

About the Records

Henry Thomas: “Ragtime Texas” has received enthusiastic reviews in Europe, Tokyo, and various national publications but has been ignored in Texas. That’s truly a shame. It is a pure delight—charming, eloquent, musical, funny. It is available from Herwin Records, Box 306, Glen Cove, N.Y. 11542, for $10.98, postpaid.

Robert Shaw: Texas Barrelhouse Piano is interesting enough but rather repetitious. Shaw was evidently past his prime as a player when he made the record. Still it does have its historical interest and is worth having if only for the sake of owning a record of songs with such blatantly down-home titles. It’s available from Almanac Records, Box 7532, Houston 77007, for $4.90.

The Treasury of Field Recordings, Volumes I and II, may not appeal to the general listener although Volume II has some wonderful cuts. To purchase them one must send an international money order for $11.50 to Dobell’s Jazz Record Shop, 77 Charing Cross Road, London W.C. 2, England.

The Lightning Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb records referred to earlier are still available and most good record stores will have them in stock or can order them. They are excellent.