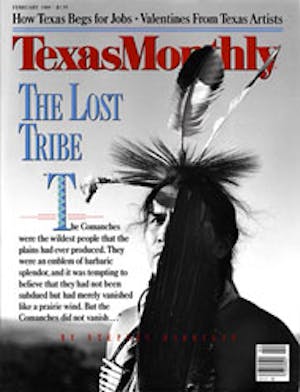

From the distance they appear to be some topological anomaly rising out of Houston’s flat coastal plain, nine promontories as high as 65 feet, covered with sparse ryegrass. These mountains are not some natural phenomena but tombs, burial mounds as revealing of how we live as Tutankhamen’s were of Egypt in the fourteenth century B.C. This is Houston’s McCarty Road landfill, 464 acres in the northeast quadrant of the city. It is the second-largest landfill in the state, growing at a rate of 14 million pounds of garbage a day. The entrance is reminiscent of an exclusive housing development. Large flags fly overhead, ducks paddle in a small man-made pond, a gatehouse requires you to announce your business. That business is disposing of trash, and it costs $14.70 a ton for the privilege. But the owner of the McCarty Road landfill, the waste-disposal giant Browning-Ferris, doesn’t want just any trash. A sign pointedly forbids the dumping of hazardous waste. Compliance, however, is generally taken on faith. At a security stop a woman in a blue uniform, with a surgical-type mask over her face, never looks in the back of the pickup I am riding in before she waves it through.

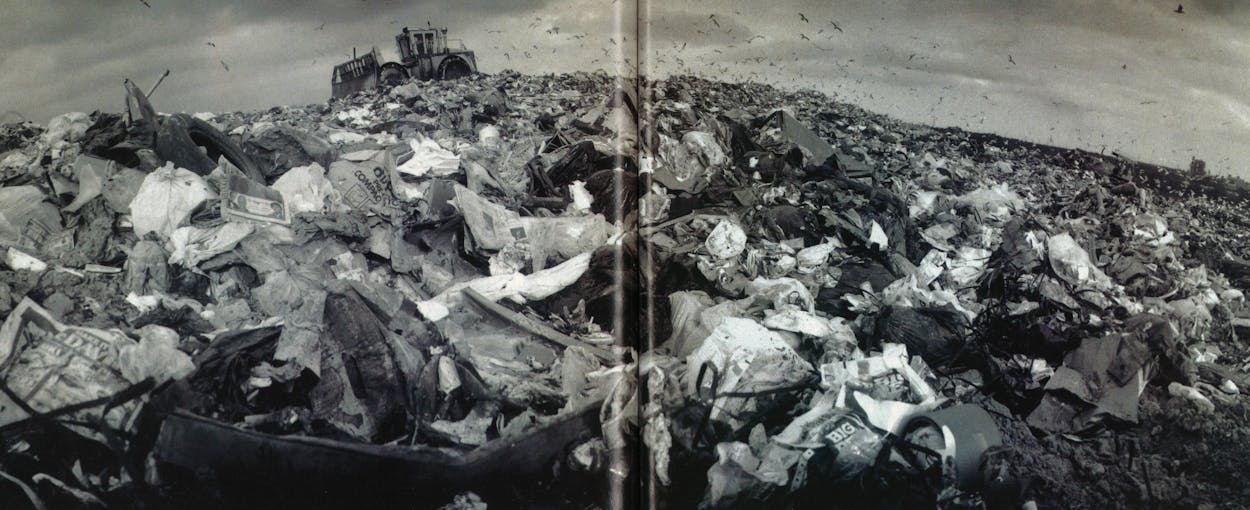

The mask is easy to understand. The odor of rotting refuse is like an assault. It sends signals of alarm throughout one’s digestive system. Inside the compound phosphorescent-yellow City of Houston dump trucks move endlessly up and down the dirt roads, like an army convoy supplying the front line. We pass an empty pit in which a bulldozer is smoothing over reddish clay, the liner for a new cell, which is a hole that starts out thirty feet deep and eventually is filled to become a garbage promontory. Farther up the road is a Valhalla of trash, a mountain in the making. Around it city dump trucks and individuals in pickups disgorge their loads, and a huge compactor, a sort of tractor with hobnails, rolls back and forth over the trash, squeezing as much garbage into as little space as possible. The refuse draws enough birds—hungry flocks of cattle egrets, turkey vultures, gulls, and pigeons—to stock an aviary. To prevent the scavengers from causing airplane crashes (they get sucked into jet engines), the Federal Aviation Administration has prohibited landfills within 10,000 feet of a large airport.

I get out of the pickup, and there spread before me is the monster all of us are creating. It is a surrealistic commentary on the way we live, full of bizarre juxtapositions. Here is a bent baby stroller, a Vienna sausage can, a small slipper made to look like a fuzzy brown animal, a double mattress printed with red roses. A disk of room deodorizer, a diaper, a Pizza Hut box, the kitchen sink. There are tree limbs, a teething ring, a living-room rug, tires, a plastic two-liter Coke bottle. An entire truck, which looks as if it has been run through a sheer like a loaf of bread, the slices leaning neatly against each other. And mixed in all around it, like batter for a fruitcake, are leaves and grass clippings, newspapers and magazines.

McCarty Road represents our most popular solution to the growing garbage crisis: burial. Until the late sixties the philosophy behind trash disposal was to get rid of it anyplace possible. Usually that meant open burning or finding a hole in the ground someone else had already dug. The most common reason for digging a large hole was to get sand or gravel to use for concrete. It was all very convenient—except that sandy soil, often found by the beds of rivers and streams, is the ideal place to put garbage only if your goal is to send it as quickly as possible into the groundwater.

The new environmental awareness of the late sixties led to restrictions on open burning, which often resulted in toxic air pollution, and the development of that seeming oxymoron, the sanitary landfill. (While today’s incinerators have pollution controls, only four small Texas cities incinerate trash.) In theory McCarty Road is as sanitary as a garbage dump can be. It passed all sorts of state-mandated tests to qualify for an operating permit. It has an impermeable liner, three feet of clay, which ostensibly keeps the trash sealed from the rest of the environment. Each day’s load is covered with a layer of dirt. When a cell reaches capacity, a cap of earth at least two feet thick is put on top and covered with grass to prevent erosion.

But the stuff is not just sitting in a hole in the ground. A basic principle of waste disposal is garbage in, garbage out. Inevitably, even the best-engineered cells crack. Landfills in Houston, with its high water table, its many natural geologic faults, its huge man-made subsidence problem, are almost designed to leak eventually. What happens is that rainwater makes its way into the landfill, mixing with the decaying matter. Through the fissures seeps a toxic soup, known as leachate. Many landfills in Texas have already contaminated the surrounding groundwater. In the worst case, the leachate makes its way to nearby drinking wells or into the aquifer. Around the country wells have been abandoned as a result. But we don’t harm just ourselves; the entire ecosystem is affected. Leaking landfills have caused fish kills in Texas waterways. Studies of streams polluted by landfills show a dramatic decline in all forms of aquatic plant and animal life. And as the contaminated water travels, it deposits poisons in the soil. Through our methods of garbage disposal, we are fouling our own nests.

As landfills age, the problems grow. The methane gas that is a by-product of decomposition makes most closed landfills unfit for further use. In Tyler the state highway department constructed an office building on top of an old landfill. After years of problems, the building finally had to be abandoned. Alarms set off by gas sensors were causing evacuations, and the parking lot kept buckling and shifting from gas pressure. Fire is a constant danger at landfills. If a fire starts, it can smolder for years in the seams that have been opened in the earth. A fire at the B&L landfill in Houston that began in 1982 was not extinguished until 1984.

For many years Texans believed garbage was a problem solely endemic to the densely populated East Coast. We could laugh at New Jersey, which exports more than half its waste. We could look down on Long Island, where taxpayers are charged $450 a year for trash pickup. But now the problem is in our own back yard. In Texas we are used to punching holes in the ground, be it for oil or water or garbage, whenever and wherever we need them. But the holes we have dug for garbage are filling up rapidly, and they are not being replaced—the public has an unshakable belief that landfills make lousy neighbors. Getting a permit for a landfill once was about as complicated as filling out an application. Today it can take an operator four years to work through the process, and it may cost more than half a million dollars. We have ever fewer places in which to bury garbage and ever more garbage to bury. The collision of these two trends won’t be pretty.

How did we get into this mess? Simple. Our lifestyle, our state regulations, and our attitudes. As Texans, we believe in unlimited resources as much as we believe that no one has the right to tell us what to do with them. As a result, we have put in place a system of flimsy laws and lax enforcement. The state is doing little to protect us from poisoning ourselves with our own garbage. And so we just go on doing it.

The Disposable Society

The flip side to being a consumer society is being a disposable society. But now we are in danger of being consumed by what we dispose. In 1960 each Texan threw out 2.65 pounds of trash a day; in 1989 we have surpassed 5 pounds a day—we’re closing in on a ton per person per year.

A closer look at McCarty Road reveals why. From pizza to pacifiers, practically everything we buy is wrapped, sometimes two or three times, in layers of cardboard or plastic or both. Remember when milk and soft drinks came in reusable glass bottles? About one third of what we now throw out is packaging. Diapers used to be made of cloth and laundered. Today they are paper and plastic and used once—16 billion wet bottoms’ worth are discarded every year in the U.S.

Another third of the trash pile is paper: yesterday’s newspaper and the day’s before and the day’s before, and magazines, office memos, bank statements. It should not have ended up at McCarty Road; paper is easy to recycle. We used to burn or compost our leaves and grass clippings. Now we’re not allowed to burn our own leaves, and who has time for composting? So we put it in plastic bags—it makes up about 18 percent of the garbage mountain. Then there’s all the rotting food—that’s 8 percent. The rest is our throwaways—the mattress, the slipper, the baby stroller, all the things we have simply finished using.

The problem is not only the monstrous amounts we throw away but what we throw away. Each of us gets rid of an estimated half-gallon of toxic waste a year. That’s not every much by itself, but multiply those miniature Love Canals by the population of a city like Houston, and it’s not miniature anymore. Things we use to keep the house looking nice (cleaners, varnishes, paints), the yard looking nice (herbicides, pesticides), even some stuff we use to keep ourselves looking nice (nail-polish remover) would be classified as hazardous if disposed of in industrial-sized drums. Then there are the heavy metals, which can be toxic and carcinogenic. Old plumbing contains lead; so does newsprint. Plated fixtures—such as those on that kitchen sink—contain cadmium, nickel, and chromium. The battery in the sliced-up truck at McCarty Road is the epitome of hazardous waste; it has heavy metal, and it is flammable, reactive, corrosive, and toxic. In addition, the asbestos we are removing from our school buildings goes directly to our landfills.

Yet there is still time for Texas. We have not gotten ourselves into the fix the East Coast is in. We can avoid its mistakes. Or we can use it as a blueprint for our own future, which, if current trends continue, is exactly what we will do.

The Enforcers

The people who are supposed to protect us from our trash are in the division of solid-waste management at the Texas Department of Health. Officials there tell you that they are not doing their job with the serenity that only an underfunded bureaucrat can bring to such an admission. In recent years the Legislature has been increasing the division’s duties while chipping away at its funding—its budget for 1989 is $1.3 million. That means we spend less than a dime per person to regulate garbage; by comparison, New Jersey spends about a dollar. California, with a population of 28 million to our 16 million, has a solid-waste budget four times that of Texas.

Rocky Stevens is the chief of the solid-waste division’s surveillance and enforcement branch. He oversees the health department’s inspectors, the people who make sure that the 934 landfills, 890 sludge transporters (“That’s probably half of them who are out there”), and 70 transfer stations approved by the state are complying with the law. “I have thirteen inspectors to cover the entire state. We can’t do our job. I have an inspector based in Temple who’s responsible for three hundred and ninety-four sites. That means inspecting more than one a day—it doesn’t include time for follow-up,” Stevens says.

When Texas began licensing landfills in 1974, it allowed existing sites to stay open with the understanding that they would make the improvements necessary to meet the regulations. Fifteen years later, almost one third of those sites haven’t—they operate with no permit but with the state’s blessing. Many landfills are still allowed to burn garbage in the open—a practice the EPA wants stopped this year. Impermeable liners are not even required at all new sites. And new landfills servicing towns of fewer than five thousand are exempt from many regulations. They don’t need to meet daily-cover standards, for instance—as if contamination respected small towns.

The odds are with those who take shortcuts with the rules; the health department doesn’t even have enough staff to collect the fines it assesses. During 1988 the division issued more than two hundred administrative penalties—but it was still trying to collect from the 1987 list.

Making sure that legal operators are abiding by the regulations is only half the job. For many people, any regulation is too much regulation. Texas is covered with illegal dumps. These include everything from what’s known as “promiscuous sites”—the cul-de-sac in the woods where people drop their trash late at night—to multi-acre enterprises where the owner can offer a low disposal fee because he has never registered with the state and therefore doesn’t bear the expense of obeying the law. The health department has 500 illegal sites on the books, a fraction of what’s out there. “The only illegal landfills we ever mess with are the ones we get complaints about. We don’t have time to look for them,” says Stevens.

When it comes to its effectiveness at protecting groundwater, the department makes James Watt look like an environmentalist. Fewer than 1 in 6 legal landfills have groundwater-monitoring equipment. Those 150 sites that do are responsible for running the quarterly tests themselves. That self-reporting makes for some interesting results. It is often impossible to tell if toxic substances are leaking, because the reports aren’t scientifically valid.

Leonard Mohrmann at the health department is in charge of reviewing the groundwater-monitoring tests. He too says he does not have time to do his job. Appropriately for an employee of the solid-waste division, Mohrmann has an office that resembles a miniature landfill: everywhere, piled in precarious towers, are papers, books, reports, and magazines—even a pair of surgical gloves.

“A lot of the data we get are of questionable validity,” Mohrmann says. “We’re getting results that don’t make any sense to me as a chemist. I find mathematical errors. I’m getting internally inconsistent data. People may be punching buttons, but no one’s looking to see if the numbers make sense.”

Even if they did make sense, they might not be very revealing, because the state standards for water contamination are so lax. “Water can pass our chemical analysis, yet it is black or yellow and it smells,” Mohrmann says.

Unfortunately, he has little time to follow up on error-ridden reports and force the operators to produce accurate ones. In addition, the division’s data processing could best be described as primitive. For example, records on groundwater are not computerized or arranged so that the results are monitored for changes over time. Mohrmann explains that the woman who was computerizing the groundwater information resigned, and the data processing has been stalled ever since.

“There’s a potential for contamination at every site in the state, if you want to look at it that way,” says Rocky Stevens. It’s not all potential. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, numerous landfills in Texas have already contaminated the groundwater. For example, runoff from the city landfill in Lampasas caused a fish kill in 1987. At a landfill in Lewisville, where waste from DFW Airport is deposited, elevated levels of mercury, chlorine, sulfate, and manganese have been detected in monitor wells.

Another danger is from long-closed landfills, which were unregulated and accepted every sort of chemical. They are now releasing their poisonous payload into the environment. The health department doesn’t even pretend to investigate those. “We don’t have time to go to closed sites. People don’t even know where they are,” says Stevens. People usually find out after the worst has happened. Take the Linfield Road dump in southeast Dallas. It is a classic, a former sand pit next to the Trinity River. While it was open, it received local industrial waste such as contaminated oil, paint solvents, ink, cyanide, and chrome. Today some of those materials would have to go into state-designated toxic-waste depositories. But Linfield Road is slowly leaching out those chemicals. There are no plans to do anything but let nature take its course; over time the contamination gradually diminishes.

With the appearance last summer of AIDS-contaminated needles on Northeastern beaches, the problem of medical waste captured the public’s attention. In Texas there are special rules for the disposal of infectious waste from hospitals, clinics, and other medical facilities. Many hospitals have their own incinerators (which are exempt from air-pollution regulations). Medical waste that is not incinerated is supposed to be double bagged, clearly marked, and buried immediately at landfills. It will probably come as no surprise that those regulations are usually ignored, and the health department is doing practically nothing about it. “The clinics don’t know what the rules are, and we don’t have the people to go after them. Most of it just goes in the dumpster out back,” says Stevens.

Sometimes the situation can’t be overlooked. Last year ten hospitals in the Houston area were warned by the health department to stop mixing waste such as human body parts with waste such as plastic utensils from the cafeteria. In Corpus Christi a health department inspector found syringes and jars of blood lying in the open at the municipal landfill. When he traced the materials back to two local hospitals, administrators insisted that they weren’t doing anything wrong.

In the short run, weak regulations and lax enforcement save tax money. But in the end, we pay the price. Cleaning up the mess always costs more than preventing it in the first place.

“Try and Make Me”

Brent Watts knows firsthand that when it comes to garbage, Texans have an attitude problem. For the past thirteen years Watts has been an inspector with the health department. He shares a 14,583-square-mile, sixteen-county territory in Southeast Texas with two other inspectors. Watts is a bald, bandy-legged, bantam-roosteresque, tobacco-chewing 42-year-old who has the frustrating job of convincing people that he means business. “This is Texas, and a lot of people think they can do anything they like with their own property,” he says. “I’ve been pushed, shoved, had guns waved in my face, been offered bribes. I was following up a complaint about a guy dumping illegally behind a trailer park, and when I went to talk to him, he shoved me three feet and said, ‘You mean to tell me I can’t fill up my own goddam pond on my own goddam property?’

“There’s a big problem in the Piney Woods in East Texas. You’ve got dirt roads and sand pits. You’ve got a way to get there, a place to hide, and a place to fill up. I had an illegal site in Houston—the guy claimed it was a wildlife refuge. He had leachate running off the site that he told me cured arthritis.”

Watts visits about three sites a day—and drives between one hundred and two hundred miles to get there. Most of his time is consumed with standard inspections of sites with permits. There are 125 in his territory, and he’s supposed to drop in on them between two and four times a year. He also spends about a quarter of his time following up on tips about illegal sites. Illegal dumping is supposed to be the responsibility of local law-enforcement officials. But they usually don’t want to have anything to do with it.

On the day I join him, Watts drives 156 miles. The first stop is the 55-acre Doty Landfill in Houston. It is a type four, meaning it accepts dry construction-type material and no putrefying waste. As we drive around, trucks full of demolished buildings or decayed trees or unfashionable furniture come rumbling through.

Watts gets out at the main dump site. He walks over a pair of purple lady’s underwear, a cowboy hat, bamboo shades, around a metal desk, and over toward three large green, suspicious-looking plastic bags. He kicks one open. Containers of food fall out. It turns out that when people come in to dump their debris, they can’t resist the temptation to throw in some kitchen garbage with the load. At the end of the 45-minute inspection Watts warns the site manager to watch out for the sacks of garbage and gives the dump a passing grade.

Then we drive north to an utterly hopeless case. We get off the highway in New Caney, and Watts maneuvers his Bronco II onto back roads shadowed by pines. We come to a five-acre clearing in the woods that looks like the remains of a small village leveled by a tornado. This is an illegal type four; the owner of the property probably simply charges a fee to people who want to deposit their building debris. There are piles of two-by-fours, fiber- board, shingles, a matching sofa and love-seat, and cans of paint and lacquer thinner. The responsibility for cleaning up such a site falls on the owner. Watts has spoken with the man. “We could fine him twenty-five thousand dollars a day, but the guy hasn’t got any money. He’s old. What are you going to do, put him in jail?” Watts asks. What’s going to happen here is not encouraging. At best, the state might manage to get the owner to stop dumping and put a layer of dirt over the whole mess. But it’s just as likely nothing at all will be done.

Except for its ugliness, the New Caney site looks relatively benign. There is no rotting garbage, no dead animals. Looks are deceiving. Almost everything disposed of at such a site, where there is no barrier against rain, will eventually leave a nasty legacy in our groundwater. Wood preservatives contain copper, chrome, and arsenic. Shingles are tar-based; they release toxic materials. Galvanized nails have zinc. The open containers of paints and lacquers are no mystery: they announce their dangers right on the labels.

The site is on low land subject to flooding. “People don’t believe brush and wood will cause a problem in water,” Watts says. “It eats up the oxygen. Tannic acid gets dissolved, and the water turns black. I’ve seen fish kills because of it.”

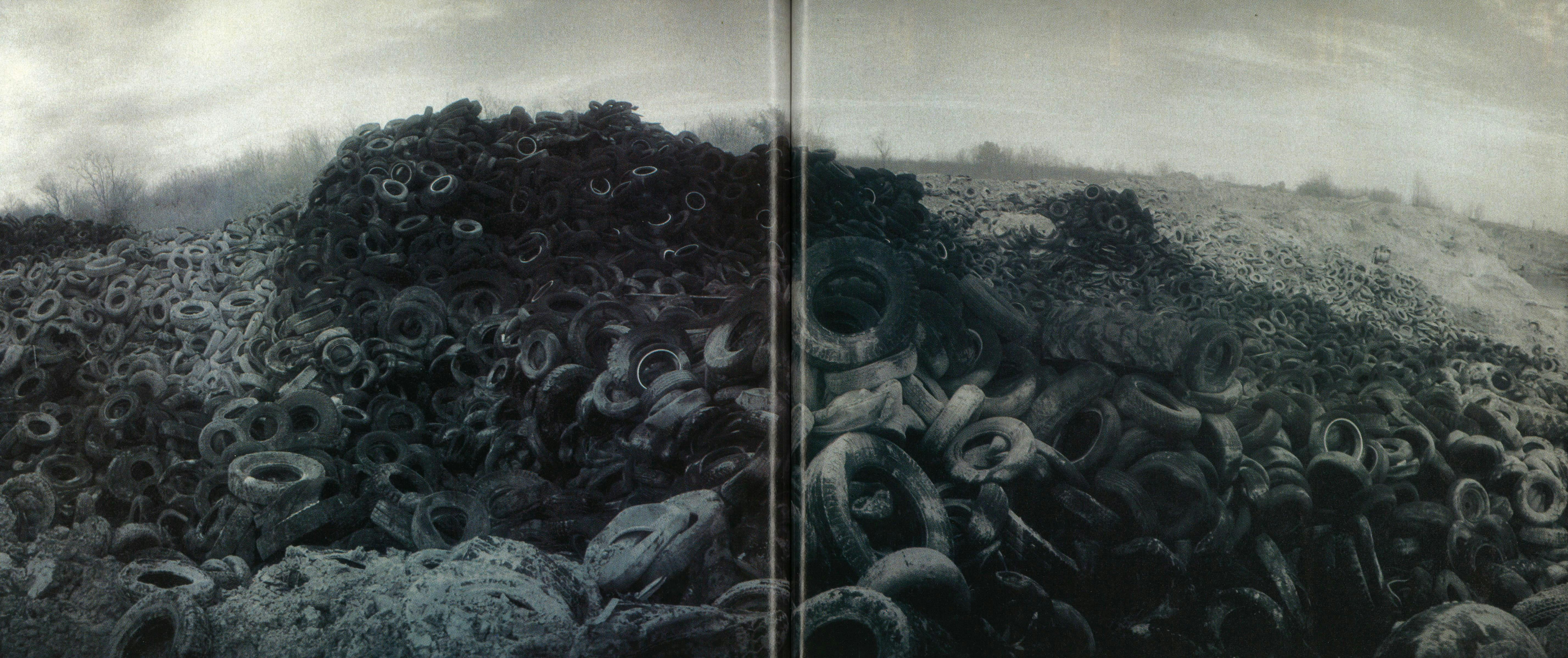

The last stop of the day is an illegal tire repository off U.S. Highway 290, 4 million tires over sixteen acres. Tires are a special problem. Texans discard about one per person per year. That’s 16 million tires. Legal landfills don’t like them—since they are full of air, they work their way to the surface and break the protective earth cover. So Texas is dotted with illegal tire burial grounds.

This one seems a culture caught in repose. Here is a behemoth from a tractor trailer communing with a small, bald discard. There is a group attempting to form a steel-belted tower. Under an agreement worked out through the health department, the owner of the illegal site is allowing his land to be excavated for sand in exchange for the burial of the tires by the excavator. The process should take two years. Because tires are nearly indestructible, they are not particularly hazardous. They are not entirely indestructible, however. While buried in this unlined sand pit they are slowly leaching zinc and the materials that make synthetic rubber.

“There are two basic rules to this job,” says Watts at the end of the day. “Always make sure you know where the bulldozer is, and always keep your tetanus shots up to date.”

Dumpy Little Towns

Sinking money into garbage strikes many taxpayers as the equivalent of throwing it away. Nowhere is that belief more ingrained than rural Texas. Take the city of Jacksboro, a community of 3,800, sixty miles northwest of Fort Worth. Its city dump has violated so many state rules that the health department has turned the case over to the attorney general’s office. To receive such special status, Jacksboro’s problems with trash were worse than most. But in many ways Jacksboro is typical of small communities: It doesn’t have the money to obey the law.

The landfill in question is forty years old. It has no liner, no groundwater monitoring, no way to collect contaminated runoff. That’s not what’s bothering the regulators. What is bothering them is that Jacksboro can’t seem to get its trash into one hole and cover it properly. City administrator LeRoy Lane says, “How do you fight a forty-year-old problem with no money? Solid waste is our second-highest expense after police. Our budget for it is 123,000 dollars. We need a new front-end loader that costs 127,000 dollars. Recently we were burning some brush, and our bulldozer caught on fire. That’s a 10,000-dollar repair we weren’t counting on.”

Complying with regulations is expensive. So, like private owners, local governments frequently create their own illegal sites. Says assistant attorney general Tom Godard, who works on solid-waste cases, “You tell them they have to get an engineer and go to Austin and file an application for a permit, and they look at you like you’re from Mars.” Local officials believe local courts will not slap them with significant fines—the maximum for noncompliance is $25,000 a day per violation. That attitude recently cost the City of Greenville $141,900. City officials decided to take a defiant approach toward state efforts to get them to comply with waste-disposal laws. They now have to pay the fines as well as clean up the mess.

Sometimes, though, the state conspires with small towns. Nederland, south of Beaumont, has been allowed to operate a thirty-year-old landfill without a permit. Nederland was supposed to fix its problems and get a permit. That proved impossible: the landfill was located in a marsh. Burying garbage in a wetland is about as sensible as storing woolens in a moth colony. Finally, last year, the health department told Nederland to close its landfill by this September. To this day the state has not tested for groundwater contamination.

Jacksboro wants to keep its landfill open. Toward that end, on a late fall day LeRoy Lane has requested that David Preister, the assistant attorney general handling the case, come up from Austin. Lane wants some advice on what his cleanup priorities should be before he and Preister have to face each other on their scheduled court date in January.

The Jacksboro landfill is ninety acres. Under the AG’s prodding, the city has started to put a cover of dirt over its active trenches. Gone too are the many open cardboard boxes filled with dead animals from the pound. The law requires that there be as few open trenches as possible on a site, but Jacksboro must have believed that you can never dig too many holes in the ground. There are several pits, up to three hundred feet long and forty feet deep, dug for no explicable reason, that now are filled with stagnant water. The pits are adjacent to filled and closed trenches, so old garbage is exposed along the wall, like fossils in an archeological dig. “I try to discourage swimming,” says Lane with a smile, peering into one pit. Because the closed trenches have not been covered adequately, tires are already working their way to the surface, breaking through the dirt.

The city has been warned to put a layer of earth on the dead-animal hole every day. Preister, health department inspector Gale Baker, and I walk into it. In the pit, lying in the open, are a skunk and an armadillo. The head of a yellow cat peeks out of the soil. Nearby are three broken garbage bags. I look into one; it contains a black-and-white dog still wearing a collar. Back outside the pit, Lane promises to do better once the bulldozer is fixed.

Still, Preister is pleased with the progress; in court Jacksboro received only a token $100 fine. Whether the groundwater has been contaminated is not known. There have been no tests, and there are no plans to do any. Yet the whole exercise may become moot. The Environmental Protection Agency has recently proposed more-stringent national guidelines for landfill operations. If they go into effect, it is likely that Jacksboro will find itself drastically out of compliance. Rocky Stevens says towns like Jacksboro may find it prohibitively expensive to properly operate landfills altogether. Possibly the only way Jacksboro will be able to comply with the law is to pick up the tab for shipping its waste to a landfill in Dallas or Fort Worth.

Waste Not, Want Not

How do we avoid ending up like New Jersey? It would be nice to think there was some big-bang solution, something scientists could cook up to make it all go away: put the garbage in the supercollider and have it superconducted to death. But the answers that exist are neither glamorous nor particularly innovative. They are in fact atavistic. We need to be more frugal when it comes to creating waste, and we need to reuse more of the waste we do create. The question is whether we ease into it voluntarily or are forced into it because of our profligacy.

Even the EPA, the sleeping giant of the Reagan years, has awakened to the fact that there is too much garbage. Its proposed new landfill guidelines would require higher standards for construction, stricter monitoring of groundwater contamination, better surveillance of what people are bringing in to dump, and continuing responsibility to look for and correct leaks for thirty years after a landfill closes. The changes will likely force many marginal operators out of business, making the landfill crunch more acute.

Texas officials too are recognizing that something has to be done. The Legislature, realizing that in paring the health department’s solid-waste budget it had perhaps been penny-wise and tons-of-waste-foolish, created a task force in 1987 to consider how to improve the program; its first proposal is to triple the division’s budget to $4.5 million. The money would come from a 50-cent-a-ton surcharge on landfill disposal. Understanding that for recycling to be successful, there must be a market for the recycled product, the task force proposes that discarded tires be turned into rubberized asphalt for highways and that more state paperwork be done on recycled paper.

One Texas scientist believes we should abandon traditional landfills altogether. Kirk Brown, a professor of soil physics at Texas A&M University, prefers the Tutankhamen model of above-ground entombment. The end result looks very much like the garbage mountains of McCarty Road, but because there is no hole in the ground to begin with, the danger of water contamination is drastically reduced. Brown has already helped design such a system for the city of Mobile, Alabama.

One of the safest things we can do about waste is to produce less of it in the first place. It seems a heroic task. Is anyone ready to go back to cloth diapers? In the East some communities are forcing changes. Suffolk County, New York, home port for the infamous gar-barge (the vessel that circled the globe looking for a place to dump Long Island trash), last year banned certain types of plastic packaging. In Florida, laws requiring that much plastic packaging be biodegradable will go into effect over the next few years.

The ultimate answer has to be more recycling. The EPA has set a nationwide goal of recycling 25 percent of our garbage by 1992, up from 10 percent today. But recycling is not magic. Glass, cans, and papers diverted from the landfill do not automatically turn into useful products. That means that recycling costs money. It still makes sense. A study of a recycling program in Minneapolis and St. Paul showed that it cost about $30 a ton to recycle waste, compared with almost $85 a ton to dump it in landfills. And every ton of waste that doesn’t end up in a landfill means more available years of use for that landfill, which means fewer landfills that need to be dug. Recycling also provides a more global kind of savings. Reusing a ton of newspapers saves seventeen trees. Turning discarded aluminum cans into recycled aluminum takes only 5 percent of the energy required to make new cans from bauxite ore.

To achieve all this oneness with the universe, some communities are making life painful for nonrecyclers. The idea is to treat garbage like other utilities and force people to pay for what they use. One New Jersey town, High Bridge, requires that residents buy a sticker for $1.25 per bag in order to throw out more than one bag a week—or else their trash won’t be picked up. New Jerseyites don’t even have a choice when it comes time to clean up the yard—it is illegal throughout the state for landfills to bury leaves. Thus the community compost pile has been revived.

Back in Texas, it’s hard to believe that Poly Products is a vision of the future. The entrance to the factory in Spring, northwest of Houston, is a muddy road filled with junk in front of a large sheet-metal building. Inside, president Gary Moore proudly points to a Rube Goldbergesque recycling contraption. The piece of equipment is a huge funnel on top of a deafening motor attached to a chute that is wrapped with cardboard and masking tape. A worker standing on a ladder is feeding ice chests—the rectangular plastic kind we take on picnics—into the chute. Out the other end come multicolored chips, ice-chest particles ready to be reprocessed into other products.

We are a society in love with plastic. It’s about as likely that the profession of milkman is going to make a comeback as that of scrivener. Plastic recycling is still in infancy, but Gary Moore is ready to be its nursemaid. Most of what he processes is waste sent directly from plastics manufacturers—boxes of ghostly looking forms, like some strange sea effluvia. Poly Products turns it into an intermediate stage, from which it becomes coat hangers, septic-tank tiles, toys, and pots for plants.

Moore is looking toward a future when what he calls “post-consumer scrap”—milk and soft-drink bottles and other plastic containers we throw away—is going to be big. In anticipation he is stockpiling milk cartons out back. He might get some help from the Legislature, which is considering a bill that would require codes to be placed on plastic containers to identify the resins used in manufacture. That would allow easier separation and more high-quality recycled plastics. Moore faces other technological hurdles. He picks up a milk bottle and scrapes a fingernail across the label. “We’ve got to figure out a way to get the labels off,” he says.

As far as Texas is concerned, he can take his time. We make it hard for people who do want to recycle—and there aren’t enough of them. Only one major city in the state, Austin, provides door-to-door pick-up of glass, cans, and newspapers. The city even gives residents buckets to put the stuff in. It couldn’t be easier—and still people don’t do it. If there were complete citizen participation, Austin could divert 24 percent of its waste from landfills. A seasonal program to pick up leaves and grass clippings would take another 18 percent. Today only 4 percent of Austin’s waste is recycled.

New Jersey, here we come.