Back in 1973, when I was a rising young yardman with an English degree, I lived in Austin on the upper floor of a house a few blocks west of the UT campus. A lot of people drifted in and out of that house, and the most unmistakable of them was Gunnar Hansen. He was only six foot four, by no means freakishly big, but he had a looming, load-bearing physical presence that was kind of epic. He had thick, Gorgon-like black hair, a full beard, and disconcertingly mild eyes. Though he could look forbidding if he put his mind to it, he was by nature a benign, pipe-smoking ruminator.

Gunnar was born in Reykjavík and wrote poetry, which made him the only person I had ever met who was literally an Icelandic bard. But his poems—which were published in a haphazard literary magazine he and I edited—weren’t heady sagas of the “I Sing of Olaf” variety. They tended to be compact and whimsical. Here, for instance, is a representative specimen, printed in its entirety:

EAT

a

nother

piece of

pie

As far as I knew, Gunnar had never had any interest in acting, so I was surprised when he told me one day that he had been cast in a movie. It was some sort of low-budget horror deal, he explained, directed by Tobe Hooper, the homegrown Texas filmmaker who had made Eggshells. I had heard of Eggshells, an experimental head-trip movie whose mystique was safeguarded by the fact that it had never been officially released and hardly anyone had ever seen it. There was no reason to imagine that the new project Gunnar was talking about would not enjoy the same obscurity. Still, he needed the work. He had just been fired from his bartending job, and there had been no uptick in the poetry business since Longfellow hit it big in the 1840’s. The money wasn’t great, only $800, and nobody would even see his face, since he would be wearing a mask of fake human skin. On the other hand, since the movie was going to be called Leatherface, he could claim the satisfaction of having the title role.

I remember Gunnar being all grumpy when he heard that Leatherface had been dropped in favor of another title, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. At that point, a year after filming and just before the movie’s release, he still had a bit of a thousand-yard stare. It wasn’t until a few months ago, when I read his recent book, Chain Saw Confidential: How We Made the World’s Most Notorious Horror Movie, that I fully realized the production trauma he had been subjected to. In addition to the endless shooting days in the summer heat of Central Texas, there had been near misses with actual running chain saws, the stuporous effects of the caterer’s marijuana brownies, and the constant stench arising from decomposing animals and from sweat-soaked actors wearing the same costumes for the whole four-week shoot.

Gunnar’s book was published in time to coincide with the movie’s fortieth anniversary this year. It’s a landmark moment for an unlikely masterwork, which Total Film Magazine proclaimed the greatest horror movie of all time in 2005—and, what’s more, the nineteenth-greatest movie of all time, a ranking that put it way ahead of Casablanca, Star Wars, and Les Enfants du Paradis. In May a painstaking digital restoration of Chain Saw’s funky 16mm film stock was showcased as part of the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes, and it arrives in theaters across the country this summer.

The first Austin unveiling of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre took place at the Riverside Twin theater in South Austin on an October evening in 1974. At the screening, I sat in the back with my girlfriend, Sue Ellen, next to Gunnar and a young woman he had just met and seemed eager to impress. It was a double date with Leatherface. The movie is iconic and ironic now, so clearly a forebear of latter-day sadistic horror movies, from A Nightmare on Elm Street to Saw VI, that it takes an effort to recall how raw and sick and effective it seemed to us at the time. We were an audience encountering it out of nowhere, with no familiar tropes to grab on to.

The movie began with an unnerving montage of a corpse being dug up and displayed in a grisly graveyard tableau, then cut to a title sequence featuring buzzing-fly music and blood-tinged, pulsating sunspots, then to a shot of a dead armadillo lying on a lonely rural road in the middle of get-me-out-of-here Texas. After that, it just got grindingly more intense. We were already full of dread even before Gunnar—in his leather mask and butcher’s apron—made his first appearance. His massive bulk suddenly filled a door frame as he brought a sledgehammer down on the head of a harmless dude with a Scooby-Doo haircut. Leatherface hit the twitching victim once more and then pulled him inside and slammed a steel door shut as he let out a triumphant-sounding gargle. The scene lasted only a few seconds but was shocking enough to provide a lifetime of nightmares. Even though I was gasping along with the rest of the audience, I was composed enough to realize I had just witnessed the most dramatic introduction of a movie character since Omar Sharif rode out of a desert mirage in Lawrence of Arabia.

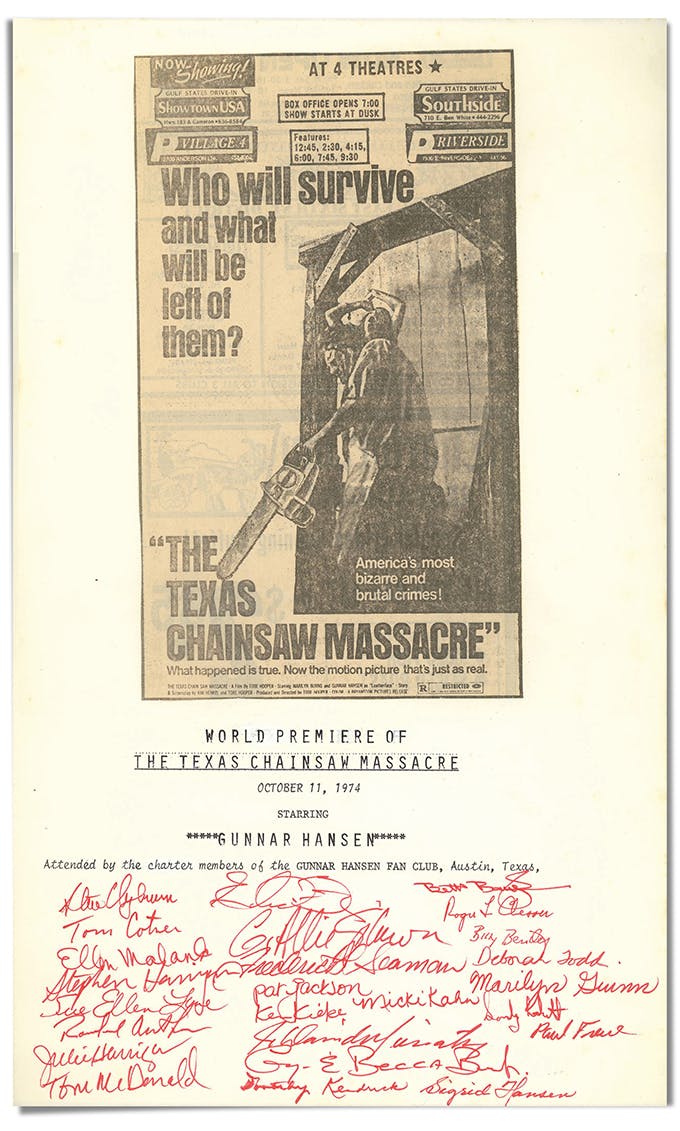

It was when Leatherface hung a screaming hippie chick on a meat hook that Sue Ellen and Gunnar’s date fled the theater. When the movie was over, we found them waiting outside. Gunnar’s date allowed him to drive her home, where she nervously shook his hand and retreated behind a firmly locked door. He never saw her again and doesn’t remember her name, but it’s likely her signature is on the document we signed outside the theater before the movie began, declaring ourselves “charter members of the Gunnar Hansen Fan Club.” As for Sue Ellen and me, we’ve been married for almost forty years, but she still hasn’t forgiven me for sitting through the meat hook scene. I’m reminded of Chain Saw’s long, toxic reach whenever we leave the multiplex after a movie that hasn’t lived up to her expectations. When she says, “If you ever take me to another movie like that . . . ,” I know that her mystic chords of memory are still intact.

She won’t appreciate my saying this, but I think Chain Saw is a good movie. I watched it recently for the first time since that 1974 premiere and was impressed by both its distinct visual style and its unfussy storytelling. It deceptively appears to have nothing more on its mind than to relate how a vanful of quarrelsome young people make a fatal mistake by deciding to stop and explore “the old Franklin place.” There they encounter a creepy family that owns a barbecue restaurant whose ingredients are, shall we say, locally sourced. (Note to Aaron Franklin, proprietor of texas monthly’s top barbecue establishment: you, sir, remain above suspicion.) The advertising claim that the movie is based on a true story is specious, but its terrors are authentic. There’s a jangly quality to the filmmaking that calls to mind the distant, disturbed era in which it was made, a time of male perms and paisley shirts, of coups and cover-ups and helter-skelterism. But its vibe reaches deeper into our primal circuitry, to the Hansel and Gretel fear of entering a witch’s house, of being tortured and killed for unfathomable reasons.

Leatherface never speaks, and of course you never see his face, but he’s by far the most expressive and unforgettable character in the movie. This is not only because he carves up most of the cast with a chain saw. (By the way, for all you prop fetishists out there, Gunnar tells us in his book that the saw was “a yellow Poulan 306A, modified with the fuel tank from a Poulan 245 and a muffler from a 245A.”) In a story where character development is mostly a question of who gets killed next, Leatherface seems to be a palpable somebody, a poignantly confused and overwrought monster who can express himself only in a squealing caterwaul. In Chain Saw Confidential, the expert writer that Gunnar Hansen has become recounts an amateur actor’s search for the voice that would be the window to his character’s soul. Told by Hooper that Leatherface should squeal like a pig, Gunnar visited a pig farm and prodded the creatures with a stick, listening for their irritated vocalizing. But he could never duplicate it. Growing desperate, he drove around Austin at night with the car windows rolled up as he grunted and squeaked. Finally, he writes, “From somewhere deep inside I let out a piercing, agonized howl. A big howl. I had to stop the car. The hair was standing up on my neck and arms. An unpleasant tingle ran down my spine.”

Thanks partly to Gunnar’s gurgling howl, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre made many millions of dollars. But due to the miracle of Hollywood accounting or something even more inventive, Gunnar never saw much beyond his $800 fee (his first royalty check was for $47.07). He passed up a part in Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes, but by the time he realized that had been a mistake, his A-list horror cred had cooled. The roles that came his way over the next few decades were in super-low-budget cult curiosities like The Demon Lover, Won Ton Baby!, Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers, Swarm of the Snakehead, Reykjavik Whale Watching Massacre, and Mosquito, for which the closest thing to a rave I could find on the Internet was that it was “filmed entirely in Michigan.”

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, on the other hand, is not just a one-off classic but a healthy little franchise. To date, there have been six sequels, none of which have made any best-of-all-time lists but which together have taken in more than $235 million and helped launch (or at least didn’t sink) the careers of actors like Viggo Mortensen, Matthew McConaughey, and Renée Zellweger.

Gunnar could have been in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre 2 (1986), but he was insulted when the filmmakers offered him only scale (“As far as they were concerned,” he writes, “it was just a guy in a mask”). The sequels went on without him, but let’s be frank: there can only ever be one true Leatherface. These days he lives and writes on Mount Desert Island, in Maine. From time to time he shows up at horror-movie conventions, and he’ll be in Austin in October for a fortieth-anniversary screening and cast reunion. His fame burns with steady low-wattage power. eBay, for instance, is aswim with Leatherface posters and action figures. There are Leatherface Christmas lights and even Lego toys. And because long ago he decided it would be more fun to work on a low-budget, low-expectations movie than look for a job, Gunnar is the only friend I’ve ever had whose likeness is on a lunch box. Any charter member of the Gunnar Hansen Fan Club will back me up: that’s immortality.