This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

PLEAS PUT DIMES AND QUARTARS IN THE BAG. I found this message inscribed in my daughter’s handwriting on a grocery sack that was sitting on the curb in front of our house.

“I need the money,” Caroline explained. She’s seven.

“But people aren’t going to give you money unless you give them something in return.”

Caroline gave me her serious look—the receptive but scared look she gives when we talk about death or divorce or any of life’s big surprises. This particular subject, money, is not one I feel comfortable advising her about. Unfortunately, I have the reputation of being a bit of a goof when it comes to handling money. My father recalls my first financial exchange, when I was still in diapers and he gave me the change from his pocket. I walked to the back door and threw the money into the yard. “That boy is going to make a senator,” my father pronounced. It’s the punch line to a story he tells rather too often, in my opinion.

I didn’t want Caroline to think of me that way, so I adopted a serious mien and advised her how she might earn a dollar. But she was not interested in cleaning out the car or sweeping the sidewalk. She decided to decorate envelopes and sell them to the neighbors. As a matter of fact, that is a good business for her. She is a delightful artist and has a keen eye for the easy mark. She colored a dozen envelopes and sold them for a quarter apiece. When she came home she looked inside her sack on the curb. Someone had left her 50 cents.

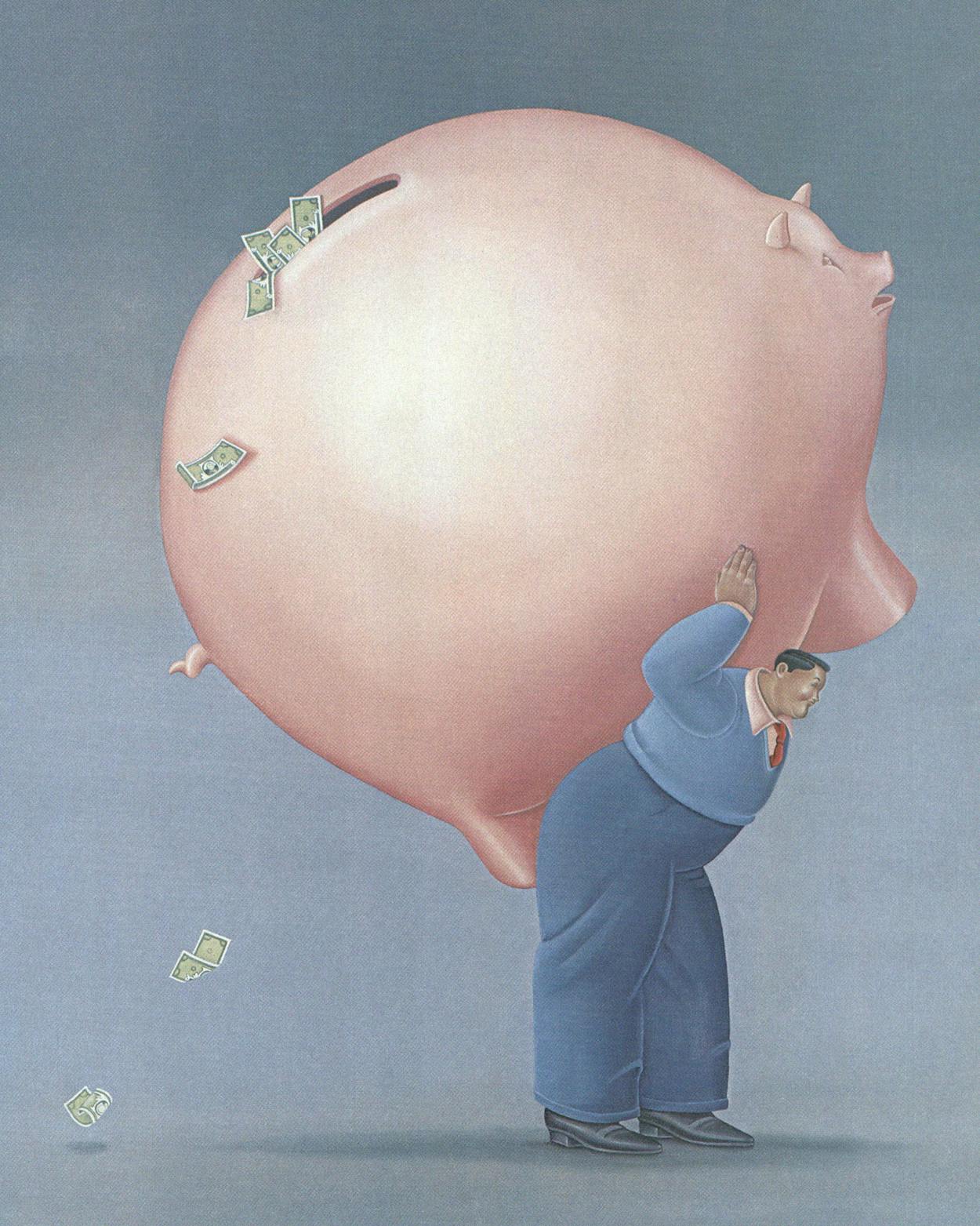

For most of my life I’ve worried about money the way farmers worry about rain, which means I think about it all the time, without really believing I can do anything about it. I sow my plans for the future and hope that fate will provide. You could say that I have a fatalistic attitude about money, but the truth is I’ve always had a secret, hopelessly unfounded belief that some fabulous windfall would one day come my way. And so financial management has never seemed that important to me.

Until recently, that is. I’m in my forties now, and my children are growing up. In a few years my oldest will be going to college, and as for my retirement, I’m already halfway through my career with almost nothing set aside. Perhaps because I know so many people in exactly the same boat, I’ve coasted blithely into middle age without worrying about whether I can provide for my children’s future or my own eventual senescence.

It’s no wonder, then, that money has been a divisive issue in my marriage and a source of anxiety to my children. Last month I decided to take a workshop called Money 101 offered at the local community college. It was a primer on how to manage one’s financial affairs, from setting up accounts to building an estate.

The class was composed of about twenty people, most of them married couples who fell into two vulnerable categories: the retired and the self-employed. My classmates were friendly enough, but I sensed that they didn’t want to reveal very much about their own situations. These days most people feel more secure talking about their sex lives than their finances.

Yet everybody I know is obsessed with how other people are making it. I remember when some of my long-time friends considered ownership of property an immoral act. I’ve watched them go from campus socialists to venture capitalists—with mixed results. Back in the Age of Money, when money was spewing out of holes in the ground, real estate was selling by the square inch, and Texas was turning into a giddy emirate, my friends talked about money with a certain contempt. Now we all sound a lot more respectful—like our parents, in my opinion.

“This is the first time we haven’t had any doctors in here,” observed Chris John, a financial planner who led the workshop along with his colleague Joan Powers. “I preach the five basics of financial planning. Number one: build up a cash reserve of three to six months of income. Number two: acquire the basic insurance—life, disability, medical, homeowner’s, auto, and liability. Number three: stay on a budget. Number four: decide what you want to accomplish with your investments. And finally number five: build a diversified portfolio.” All this sounded both sensible and impossible.

Homework after the first class was to go through our household expenses for the last six months to determine how much we actually spent. Using that information, we would then set up a family budget, a joyless process that I put in the same category as choosing a cemetery plot.

The facts of my financial life are these: I am a self-employed writer. In the parlance of the day you could call me an entrepreneur, which means that I have an unpredictable and highly fluctuating income. My wife, Roberta, teaches kindergarten for the Austin Independent School District. We have two dependents, Gordon and Caroline, who were worth $1,950 apiece in terms of last year’s tax deductions. We own our home, a duplex we bought in 1980 for $114,000. Because we rent out the other part of the duplex, our net housing cost is less than $400 a month—a figure our friends look at with envy and disbelief.

We don’t live extravagantly. Roberta and I go out to dinner together about once a week. Occasionally we go to the movies, but rarely more than once or twice a month. Every summer we go camping for a couple of weeks in Colorado. On the road, we make sandwiches in the car and try to stay in a Motel 6. Our children wear a lot of hand-me-downs. I haven’t bought so much as a sport coat for the last two years. We have the usual heavy grocery expenses for a family of four, but we don’t eat meat nearly as much as we used to. We have two cars, a 1986 Chevrolet Suburban that costs us $387 a month (only twelve payments to go), and a 1972 Volkswagen that’s long since been paid off. We are a frugal family. On the face of it, we should be able to coast on thirty grand a year.

Because my income varies so wildly, I could only guess at what I might make this year. I decided to be optimistic. I calculated our total family income at $60,000, which would be a better-than-average year. That’s $5,000 a month. Right off the top comes $1,500 in taxes (self-employment taxes run it up), leaving us $3,500 to pay all our bills. Our household expenses actually run close to $1,500 a month, once we take into account the utilities, the phone, maintenance, and child care. The cars cost us $700 after gas, insurance, and repairs. We’ve had a lot of dental work recently, which isn’t covered by our insurance, so our medical costs have been high the last few months—about $500. Add in life insurance and debt service, and that leaves us only a little more than $500 a month for everything else—food, clothing, charity, laundry, toiletries, entertainment, music lessons, Christmas, allowances, haircuts—an amount that could easily approach $1,500 without seeming excessive. That still doesn’t allow for symphony tickets or a weekend in San Antonio or the new car we’re bound to need soon. By my calculations, we require $84,500 a year just to get by.

“Ninety percent of money is attitude,” Chris had told us. That sounded helpful to me. After all, there are stories in the paper all the time about people who have grown rich on modest salaries.

I began to wonder if I was making this too hard. There’s a school of thought that says that Money Is My Friend and You Can Have It All—to name only two of the titles on this subject on Roberta’s bookshelf. Prosperity consciousness is what these books preach. The universe is abundant; it’s only negative thoughts and beliefs that stand in the way of your personal fortune. This seems to me the same line of thinking that believes a chain letter will bring you a million dollar bills. Moreover, it suggests that rich people are on a higher spiritual plane than the poor, a presumption I violently dispute.

The other day I was leafing through one of those volumes, and I found a list of affirmations about money. “Money is safe for me,” the list advised. “I already have enough money. I understand money easily and it’s fun.” These are the kind of statements I tend to sneer at. Then I turned the page over and read the negative beliefs that such affirmations are supposed to reform. “Money is my enemy. Money is crass. I am unable to manage money. I’ll never have enough money. I don’t deserve money. Investments I make are no good and a lot of trouble. I’m doomed to worry about money forever,” and so on. Every negative statement on the list was something I profoundly believed.

How did I get such a bad attitude? As a child I loved money. I’m not talking about money, the arbiter of social worth, the despoiler of values, the pitiless scythe of divorce. I’m talking about money, the physical object. I was a coin collector.

Rare coins or proof sets that mustn’t be touched did not interest me. The pleasure of collecting was in raking through the pile. That’s what “handling money” meant to me then. I liked to stack the mud-colored Mexican centavos and peek through the BB hole in the Turkish kurus. Afterward, the hands of the young numismatist would smell of metal, an odor both sharp and fruity, and a bit corrupt, like an adult underarm. There was a sense of solidity and permanence with coins that you didn’t get with stamps; in fact, some of my coins had outlasted the countries that minted them. Shape and size and heftiness mattered, denominations did not. It pleased me that the British penny was so big (if you had fifty such pennies in your pocket, how would you keep your pants up?) and that the bitty French centimes and the silver Dutch ten-cent pieces were small enough to get caught under your fingernail. I loved the square nickels from Ceylon and the Cypriot piasters that were fluted like pie crusts. This was still a time when Canadian money migrated even to Texas as worthy counterfeits, and on those occasions when I went through my mother’s purse and found a dime with the queen on it or a maple-leaf penny—why, that was all I needed from a day.

Earning money was a different matter. My father tried to teach me the labor theory of value by making me work hard for my allowance. I was more interested in the easy buck. When I was Caroline’s age I used to sell sticks to a deranged, hollow-eyed veteran of the Korean War. He would walk through the neighborhood, offering kids a quarter per bundle. Once, while riding my bike through the alleys, I found his house—it must have been his house; the back yard was piled high with sticks. The rumor among the kids was that this was a form of composting he had learned in a Chinese prison camp. After I boasted to my father about how much money I was making in the stick trade, he sat me down and explained that some forms of commerce are not honorable. If one gets money in a transaction, one must give up something worthwhile. (It was the same speech I gave to Caroline 35 years later.) Absorbing my father’s wisdom, I went to our next-door neighbor and tried to sell her the love letters my parents had written each other while my father was fighting in Europe.

No doubt my ambivalence toward money stems in part from my relationship with my father, who struggled out of the dust bowl in Kansas to become a prosperous Dallas banker (keeper of the money). I suppose that by becoming a freelance writer, which guaranteed an episodic, if not catastrophic financial life, I was expressing contempt for the bourgeois values my father represented. On the other hand, I wonder if there might be a biological explanation, some as-yet-undiscovered gene that predetermines one’s financial attitudes, a Yes Money/No Money chromosome that is as immutable as the shape of an earlobe or the length of one’s toes. Here I’ve wandered into the old heredity-versus-environment dilemma. In either case, money doesn’t stick to me. They have done studies on sweepstakes winners and found that most of them run through their fortunes in a couple of years and find themselves back where they started. I suspect the same would happen to me.

And yet I’ve always worked hard for money. I got my first job when I was fourteen, busing tables in a hamburger joint. At the end of the summer, to my astonishment, I had accumulated $1,400 in a savings account. I withdrew the entire amount and purchased two tickets to Europe on the Queen Mary for my parents’ anniversary. That was the kind of gesture that appalled my father. He refused the gift, of course. Had he accepted, control of the family would have passed subtly into my hands.

My happiest relationship with money was during the two years I taught school in Egypt, which has a “soft” currency—in other words, its real value is rather less than its stated one. An obscure law of finance decrees that the softer the currency the larger the bank notes, and the Egyptian pound had swollen to the size of high-school diploma. What I liked about this money was that I absolutely had to spend it. There was no point in saving, since the pounds would turn into Monopoly money as soon as I crossed the Mediterranean. My financial life was pleasingly simple and in a way quite gay. So I would say that my problems are confined to the harder currencies—the dollar, in particular.

It took only one Money 101 class to drive home a truth about money: If you spend more in one area of your life, you will have to subtract it from another. As I reviewed our expenses, I sorted them out into piles, like laundry. It was a shock to see how much we spent on gas, for instance, and unintentional expenses like service charges and library fines.

A few days later I was changing the oil in the Volkswagen, a task I hadn’t performed in years, when a fellow on a motorcycle wheeled up. When he lifted his sunglasses I was startled to recognize an acquaintance of mine, an accountant who lived on a little estate out at the lake and drove a BMW. Or did.

“That’s all gone now,” he told me. “I’m scaling back.” He was living alone in an apartment in town, “just surviving,” a victim of the bust. I see them all over the place—old friends who used to have the world on a string, now stripped of their assets and reduced to negotiating their debt. The ones who aren’t bankrupt are in the “bad bank”—the purgatory for nonperforming loans.

“Keep out of trouble,” my friend advised as he roared off.

I poured another quart of oil into the VW’s engine and thought about the Age of Money. Back then, my luckier friends drove European cars, sent their children to private schools named Saint This or Saint That, spent their evenings going over architectural plans, and generally lived life as it is glimpsed in the magazine ads. Sometimes Roberta and I made the mistake of going out to dinner with them, spending as much as a hundred bucks for the pleasure of their company. At the end of the meal, dollars would fly onto the table as we split the tab. Now, when Roberta and I go out, we spend for the meal what we used to leave for the tip.

That was a trying period for me. I envied my friends, but I didn’t admire the way they made their money. They had not exactly earned it; they had gotten it through cleverness and good timing. They were the kind of people who do well at parlor games, and that was what life felt like when we were with them—brisk and competitive, a barrel of laughs.

“I’ve always wanted to do what you do,” an editor once told me as we shared a cab in Manhattan. I love my work, but I become suspicious when a wealthy editor tells me how lucky I am.

“So why don’t you?” I asked.

“Too much money,” he sighed.

I’ve heard it before: Poverty motivates; wealth enervates. Also, the best things in life are free, money doesn’t buy happiness, etcetera. Rich friends have actually said those things to me. I see the evidence in their own lives—the materialism, the superficial quest for profit, and frequently a kind of stagnation of the ego. People who inherit fortunes seem to lose vitality; it’s as if they’re dragging their millions around in coin. They don’t have the drive to get ahead because they are ahead. And yet the peace of mind that should come with that knowledge eludes them. I would suppose they would become scholars or philosophers or write the book they’ve always talked about, like my editor friend. Instead, they become epicures. They spend their time spending money. Or else—and this is worse—they hoard their wad and spend their time not spending money, like Jack Benny scraping the uncanceled stamps off envelopes. In either case, money is it for them, the center of their lives.

When we talk about “selling out” and “prostituting ourselves,” we are speaking of trading virtue for money. Another way of saying this is that people are willing to pay to see virtue destroyed. I know it’s the American way, but my heart sinks when I see someone I admire doing a television advertisement. It was sad watching Senator Sam Ervin go from being the hero of the Watergate hearings to the wheezy “Do you know me?” character of the American Express commercial. He was cashing in on his virtue, selling off my faith in him as an honest man.

If I were king or even the commissioner of baseball, I would declare a moratorium on discussions of how much athletes are paid. I hate knowing that Ozzie Smith makes two million smackers a year fielding ground balls for the Cardinals. I loathe hearing the broadcasters work that out to $17,000 per chance or whatever. It leads me to think about comparative values—about schoolteachers and nurses, for instance, who make a hundred times less than Ozzie Smith. Why should they have to wait tables at night while the lawyers and arbitrageurs dine?

Listen to me rail. But the truth is I dream of hitting it big all the time.

Back in the Age of Money, just before the market in Texas real estate collapsed, Roberta and I talked ourselves into buying another rental property with a friend of ours. It was to be a first step in building our real estate empire. Every other week there was another seminar at the Sheraton given by some self-made millionaire whose message was that property was the path to wealth, and that one could make a fortune with nothing down. On the force of so much conventional wisdom, we went out and bought a tidy little 3–1 across the street from a church. We paid $62,500 for it in 1985. The city now appraises it for $34,000.

If you are not a landlord, you may not be familiar with the concept of the “negative.” In a period of rising property values, the rent you receive may not cover the cost of your mortgage (in other words, you have a negative cash flow), but you “accept the negative” because your investment grows more valuable each month. Also, the tax code favored such investments because it allowed you to generously depreciate the property and pass along losses to offset other income. In the context of the time, a negative was a nice thing to have. We believed in it, the way people used to believe in using leeches to bleed a patient back to health.

The negative we accepted when we bought the house was $5 a month. Now that little bloodsucker has grown to $200 a month—when we’re fortunate enough to have it rented. The tax code has changed, and although as a citizen I approve of the changes, as a landlord I feel betrayed. We can’t afford to own the house, and we can’t afford to sell it. The cost is equivalent to financing a mid-size American car, one that we never have the pleasure of driving, only of servicing every month.

Not long ago I sat on a jury in Travis County. During a recess in the trial, I walked outside to get a breath of air. There was a clamoring mob fighting over a sheet of paper that was being passed around. I had always heard about the sale of foreclosed properties on the steps of the courthouse, but this was the first time I had ever seen it. It gave me quite a chill, knowing that my own unfortunate investment could come to the same end.

The following Saturday morning Roberta was sitting in the music building at the University of Texas with some other mothers of string-project students. One of the women had had her house on the market for months, and Roberta asked whether she had sold it yet. “Well, we deeded it back to the bank,” the woman said. “We lost a hundred thousand dollars, but it’s off our backs at last.” There was a sympathetic pause, then one of the other mothers asked, “How do you do that? Is it better than foreclosure?” It turned out that every mother in that circle was thinking the same thing: They were all looking for some escape from their crushing financial burden.

The Age of Money died of shock on Monday, October 19, 1987, the day the Dow Jones industrial average fell 508 points. My first action when I heard the news was to turn off the air conditioner. Don Regan, the former Secretary of the Treasury, was on TV, telling us that we would all have to work very hard to keep from losing our entire economy. I switched it off and walked out into the mild autumn twilight and watched a free sunset. I thought about tearing up the yard and extending the gardening or doubling up the kids and taking in a boarder. I was exhilarated. I understood why the Depression is remembered so fondly by people who describe how awful it was. The details of life had a particular crispness; it was like the day I got my first eyeglasses. I watched Caroline pluck a carrot out of the garden and dress it in a napkin and a single boot from a Barbie doll. She called it Baby Carrot. The smallness of this action seemed to foreshadow what life would be like from now on.

All of my life I had depended on certain guarantees. One was my father’s money. It would be there if I failed. It would help pay for my children’s education. Some day it would provide a modest degree of security in the form of my inheritance. Those assumptions were wiped away on Black Monday. Half of my father’s net worth was wiped away in a single day. He had already lost heavily in his Texas bank stocks. Although the market would rebound, and with it most of my father’s portfolio, the assumptions I had lived with were permanently changed.

Many of his friends, including some of the most respected business people in Dallas, were ruined by the bust. Men like my father had spent their lives building the mighty insurance and financial companies that raised the city of Dallas a hundred stories into the air. Now, at a time when they expected to be living off the rewards of their labor, they find themselves in bankruptcy. Some of them may be facing jail terms. A few have committed suicide.

My father counts himself lucky that he has a successful one-man consulting business going in his retirement. And yet, like me, he is still pondering the lessons of the bust. It was not just the parlor-game boys who came to ruin, it was the prudent types as well. People who devoted their lives to making money fell the farthest, while people like me merely felt the wind.

I sat on the couch, working on the most dreaded part of my class assignment: the family budget. Roberta avoided me as I grumbled and fussed through the figures. Money is a matter of contention between us, as it is for most couples I know. Recently I was standing in the kitchen of some friends of ours when the wife made some complaint about the cost of the bakery bread the husband insists on buying. “What about your coffee!” he said with an edge in his voice. He drinks tea, which he contends is cheaper. What struck me about the exchange was how quickly it became heated and how familiar it was. It’s a scene Roberta and I have played out a hundred thousand times.

Saving is supposed to be a part of our budget. We have to think of our children’s education and our own retirement. The college expenses are of particular concern to me, since Gordon will graduate from high school in five years, and his education fund has only $1,200 in it.

Five years from now that $1,200 should be worth $1,933, if it grows at a rate of 10 percent per year. By that time, four years of education at a public school, including room and board, tuition, books, and supplies, will cost $38,857. According to a table of inflation-adjusted rates, I will have to raise only $6,052 a year between now and then to avoid taking out a loan for Gordon’s education. If he wants to go to private school, that figure rises to more than $11,000 per year. Figuring in Caroline, who hits the campus in the year 2000, I need to be saving $305 a month if they go to public school, $542 if they start thinking about Stanford or Rice.

Then there’s the matter of my retirement. I have no pension except what I force myself to put into my SEP-IRA account. Roberta may expect an annuity from the Teacher Retirement System if she can afford to continue in the profession. To live the sort of life we would like to live in our older years, one in which we have at least $2,000 a month in today’s income above our social security and Roberta’s modest pension, we would need to have a monthly income of at least $8,644 in the year 2019—assuming that I retire in thirty years when I’m in my early seventies and that the rate of inflation averages only 5 percent a year. To accomplish that, I’ll need more than $1 million in investments earning 12 percent a year. To save that amount, I need to start setting aside a little over $3,000 a year—right now.

Lessee . . .

It doesn’t add up, of course. I’m running a deficit just getting through the month.

After I had gone through the dismal process of discovering exactly how awful our affairs were, I announced to Roberta that I was prepared to propose our new family budget—the one that assumes we can live on the $60,000 a year we don’t actually have. She knew how hard it had been on me to face up to our money problems. I had been grouchy and sleeping restlessly for a couple of nights. Roberta sat beside me on the couch and put her arm around me. “I’m ready,” she said sweetly.

By the time I had gone through the first column of figures, she was on the other end of the couch with her arms crossed. “We can’t live on that!” she exclaimed.

I felt my personality abruptly turn cool and analytical. My forefinger rested on my temple and the rest of my fingers covered my mouth—the detached pose that sends Roberta up the wall. In fact, I’m not at all cool about money; it makes me feel inadequate and defensive, which is why whenever we talk about it, I go into an emotional freeze. All I have to do is hold this posture for thirty seconds, and Roberta goes into meltdown.

Her own parents had been foolish with money. I don’t know what Roberta expected when she married me. When we met, I foresaw my adult life as being lived in a SoHo loft in an endless bohemian reverie. I never imagined myself as an entrenched defender of the middle class, with “a wife, house, children—the full catastrophe,” as Zorba described it. My ambivalence about who I turned out to be makes Roberta shiver. As a child, she never had the assurance that she could depend on her father, an alcoholic doctor whose legacy to her was an old stereo and three hundred stamped business envelopes. She alternates between her spiritual belief that the universe is abundant and will provide for us and her emotional conviction that at any moment a trap door will spring open and we’ll tumble into Chapter 11.

Even my children have dreamed of my failure. In those dreams, they ride to my rescue, becoming child actors or rock stars. They buy us the new car and the larger house we’re always talking about. This is a repeated theme in their lives. I know such a family, however, in which the child became a wealthy television actor. The father, who was a printer, quit his job and began spending his days at the dog track. He had no need to support his family—his twelve-year-old son was doing that—so he bet away his life savings, hoping for a run of luck that would bring back the satisfaction and authority he enjoyed when his children were younger and he was making a union wage.

Because of Roberta’s insecurity and my children’s needs, I am determined to become fiscally responsible, even if my family hates me for it. The resentment they feel because we can’t afford to go to the movie or buy a $110 pair of Air Jordans is not as shattering as the fear of not having enough to get through the month or to send children to college. I want to be prepared for the hazards of life as well as its opportunities. I want to feel, and I want my family to believe, that our life is going to get better, that we are building toward a secure future, and that the harrowing swings of fortune in my career won’t leave us suddenly bereft.

Last summer Roberta and I went for a walk on the beach in South Padre Island. The topic was money, and Roberta was in tears. I had spent months working on a speculative writing assignment, using up most of the advance on another book I was contracted to write. It was a characteristic risky maneuver on my part. Once before, I had taken off a year to write a novel that failed to get published, and our finances had never recovered. Now I seemed to be engineering another disaster. “I want you to write whatever you need to,” she said. “I just don’t want to suffer because of it.”

Tears came to my own eyes. I was torn between my responsibilities—to my family, to my career—and I saw no way to reconcile them. I felt defeated and incompetent.

Suddenly I saw a quarter gleaming in the sand. I picked it up and handed it to Roberta. Then the surf rolled back and I saw more money scattered there—nickels and dimes polished by the seawater. I felt that we were standing in some weird margin between reality and the supernatural. Here we had been arguing about where our money would come from, and now it seemed that the universe was hurling the answer in our faces. Perhaps one can make too much out of finding 85 cents lying on the beach, but I often think about that magical incident. For most of my life I’ve approached money emotionally, and I’ve struggled to become more rational about the subject—to treat money as a simple tool and not as a measure of my character. But at that moment I believed that money was as much a part of the spiritual world as of the material one. I gratefully scooped up the lustrous coins and pressed them into Roberta’s hand, crying, “I will provide!”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads