This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In the middle of the wide dirt floor of the AstroArena, a high-jump bar has slowly been raised, two inches at a time, much to the delight of the rowdy crowd. A blue plastic sheet is draped over the crossbar so that Popcorn can see it more clearly, which is supposed to make him more willing to jump over it. And if he isn’t willing, of course, he won’t try. Everybody knows you can’t make a mule do something.

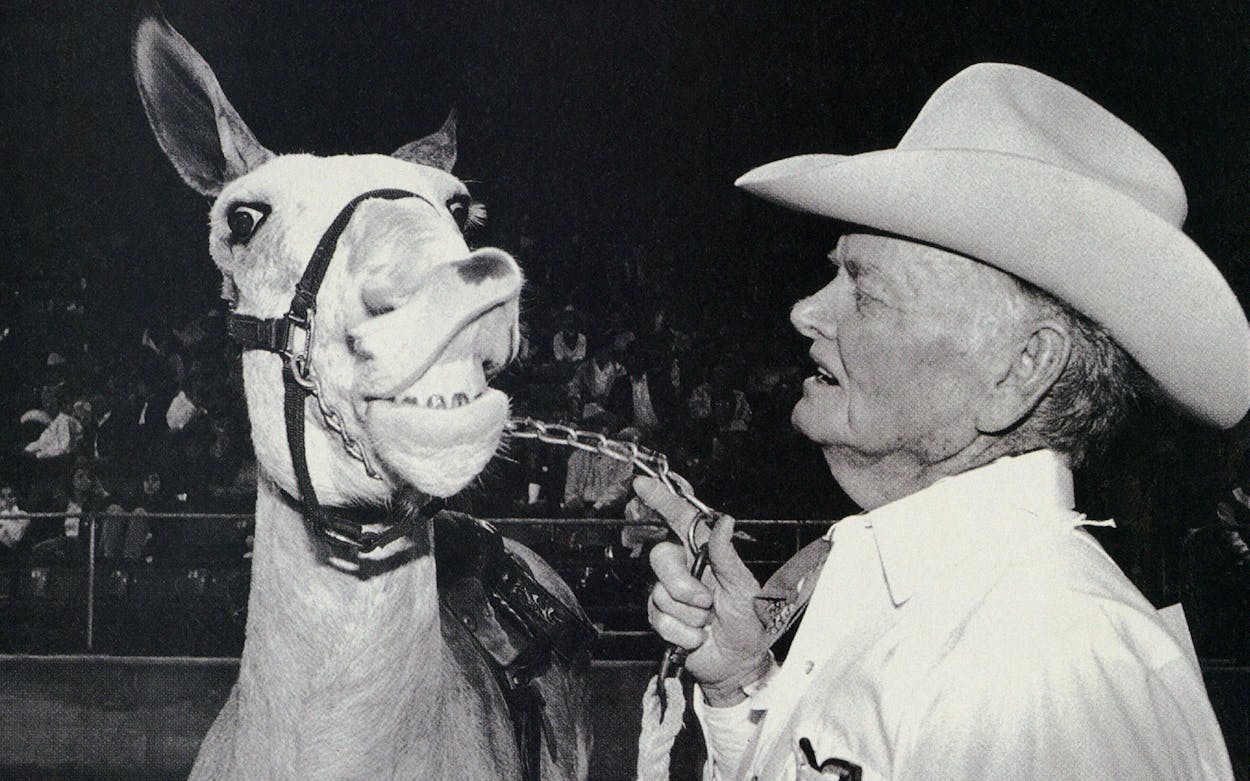

“Be gentle, look at you,” coos Red Roper, tugging on Popcorn’s halter. The animal resists approaching the bar, but not as much as he might. Roper repeats the mantra: “Be gentle, look at you.”

The spectators at the 1991 Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo bellow encouragement as well, cheering the ridiculous behavior as they would a demolition derby. They all know that mules don’t jump over things. Infamously slow but sure-footed, the mule of stubborn lore won’t step over a fallen tree branch; he’ll walk for miles to find a crossing for a foot-wide stream; a dark shadow can stop him dead in the road, frozen in trepidation.

The very absurdity of a high-jumping mule is what thrills the three thousand people—one third of them children—in the AstroArena stands. Giddy with the moment, they shriek and shout for Popcorn to go for it, come on, just do it, jump already! The bar is at five feet six inches, well above the mule’s shoulders. He doesn’t appear to be in any hurry to attempt it, backstepping from side to side, fighting the rope.

“Be gentle, look at you,” continues Red Roper in a soft but urgent voice.

Roper’s given name is Charles, but he has been called Red for 63 years in reference to his hair, now gone strawberry gray. As if to compensate, he wears flashy knee-high scarlet boots and a red bandanna, and looks very dapper. In the small Old West world of professional mule trainers, the Brashear rancher is the champion showboat and star.

“I don’t wanna be braggin’,” he’ll say with a big sly grin, “but I like to think everybody started followin’ my pattern after I started trainin’ mules. Nobody ever told me a mule couldn’t do the same things a horse could do. I won the state fair in Dallas six years in a row with a reining mule, and it was national champion twice.

“The secret to trainin’ a mule is get his confidence. You prob’ly heard that old wives’ tale: The way to get a mule’s attention is with a two-by-four. Well, that’s out. It takes time and patience, lots of it. But once that mule learns confidence in you, he’ll train a lot more readily than a horse will. They’re so much smarter than horses, but they’re more cautious. That’s why they’re smarter.”

That’s the sort of logic you hear from mule trainers. To hear a mule person talk, you’d think a mule is the smartest animal on dry land: craftier than a fox, more loyal than a dog, with a longer memory than an elephant and more lives than a cat. And beyond any question, a mule is the superior embodiment of all that is best in the equine genus.

Equus asinus, the donkey, has been Western man’s most common and thus low-rent beast of burden since biblical times. The pregnant Mary and the populist young king David both rode asses to their glory. We cannot be sure if the animals were purebred donkeys or if they were mules as we define the breed today, but we can be certain that they were not horses. Horses were reserved for Romans and pharaohs.

Like most mules, Popcorn was sired by a male donkey (a jack) on a mare, in his case, a bay quarter horse. Occasionally a breeder will reverse the hybrid, mating a female donkey (a jenny) with a stallion, which produces an animal much more horselike in appearance—without the cartoon ears or the coconut-shaped head—known as a hinny. Both half-breeds are sterile, a race of individuals unable to evolve, which may account for their paranoia.

To hear a mule man tell it, mules receive from the donkey parent their intelligence, their reliable good health, their simple needs and stalwart endurance, their strong bones and small hooves, their obnoxious honking bray, and their careful step. All they really get from the horse side is longer legs, some big smooth muscles, and a touch of color.

The union of jack and mare is a mismatch of considerable proportions, given the donkey’s diminutive stature and the horse’s high-tailed G-spot. It’s difficult to imagine how mating might be performed in the wild without man’s assistance. Today big-time mule breeders use artificial insemination, but smaller operations install the mare in a breeding chute that has a convenient ramp in the back called a jack-stock.

The first American mule tycoon was none other than George Washington, who had the advantage of a pair of jacks sent to him by the king of Spain, where the world’s best donkeys were bred. Washington’s mules, together with his slaves, were the basis of his fortune.

In the Old West it was Spanish donkeys and mules from day one. The trappers, hunters, traders, packers, prospectors, stage drivers, and sodbusters who opened the land all did so with burros. Our dashing image of the West being won on horseback is a romantic cinematic misconception. The typical horseman was General George Armstrong Custer, an early yuppie more concerned about how he looked than what he was doing. The Indian fighter who got the job done, General George Crook, was a die-hard mule man.

Then along came railroads, trucks, and tractors. Mules were the first creatures to be put out of work because of automation. As the demand for their services plummeted, their numbers dwindled. The breed was kept alive by nostalgic rednecks who recalled their childhood on red-dirt farms, where a good mule made the livelihood possible. Mules were cheap to keep and feed, they never had vet bills, and they were surprisingly handy.

It should come as no shock that Texas A&M is a hotbed of mulish activity. Gary Potter, a professor of equine science at the College of Agriculture, is widely regarded as the foremost authority on contemporary asinine matters. He is a tall, broad man who looks sort of like the softer younger brother of some mean old Texas Ranger. He wears a Stetson hat and one of the many rodeo belt buckles his mule teams have won.

“My dad had mules when I was a kid in Arkansas,” says Potter, who is 48 years old. “We used them to log woods. I skidded logs with them when I was barely big enough to see over them. Dad always had a team, and I just kind of grew up with them and liked them.

“I’d lot rather drive mules than horses. Riding, that’s another story—the riding qualities of a horse are a little better. Now, I’ve seen a few mules that’ll ride as good as a horse—my dad had one—but not many. Driving them, though, that’s something else.”

At this year’s Houston Livestock Show—where the mule show took over the AstroArena while the rodeo finals went on in the Astrodome—Potter’s teams won four first-place buckles and five ribbons in various driving events. Pulling big dray wagons, they negotiated obstacles, backed up, and parked with a nimbleness scarcely imaginable in an eighteen-wheeler. They made turns tighter than a Porsche.

“The most noticeable trait in mules is their inborn sense of self-preservation,” says Potter. “Like, if you had a mule out in a pasture someplace and he happened to get his leg hung in a fence? The chances of him hurting himself trying to get loose are not very good. But if you have a horse get hung in a fence, he’ll hurt himself. Every time.

“And a donkey doesn’t respond to negative reinforcement much. You can scold and spank and bang around on them and stuff like that, and they’ll just kind of hump up and take it. If you scold and bang on horses, they’ll get flighty and run off. A mule’s kind of in-between. You can scare a horse into nearly anything, but you can’t scare a mule.”

Red Roper sure wishes he could. Right now he’s struggling to keep Popcorn inside the twelve- by twelve-foot square marked in the dirt beside the crossbar; if the mule steps out of it, he’s disqualified. Roper thinks something in the stands has caught Popcorn’s attention. Mules are notoriously distractable. The first two rows of seats are kept empty for that reason, but it’s hard to believe that it does much good. There are, after all, three thousand yelling mule fans, all calling for Popcorn to get on with it. Jump!

The mule show has been part of the annual Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo (the world’s biggest, of course) since only 1984, when it began as a sideshow in a warm-up arena. “I’ve been on the quarterhorse committee here for thirty-five years,” says Red Roper. “And I kept trying to get ’em to have a mule show. All my friends, from president on down, they’d tell me, ‘Red, this is Houston, and we gotta be number one, and we don’t believe a mule show’ll go.’ Then, finally, a few years back they said, ‘Well, we gonna try it this year and see what happens.’ So from then on, this here’s the number one mule show in the country.”

From Missouri to California, indeed throughout the West, mules are becoming a major attraction at livestock shows. It’s part of a larger trend in the Western horse industry that has put greater emphasis on roping and cutting horses, and working horses in general. Of course, back East horse people still flock to see and buy effete, omni-gaited prancers, the equine equivalent of poodles.

The most frenzied and crowd-pleasing event at any mule show is the mule pull, a contest that might have prefigured the monster-truck rally. Pairs of harness mules are hitched to a sled piled with lead weights and given ninety seconds to pull it ten feet. More weights are added, eliminating teams until one team wins. Huffing, puffing, eyes bulging, the mules strain to drag two, nearly three times their own body weight while the audience goes wild. Children especially love this event. It might seem abusive were it not for strict rules—no whips, for instance, no touching the animals at all—and the mules’ own renowned unwillingness to do anything they don’t feel like doing.

“They know their limits pretty well,” says Potter. “If they get more than they want to handle, they’ll just lean into the harness and fake it, and there’s not much you can do about it. Mules like to pull, generally, but they’ll quit as soon as they stop liking it.”

Most mule show events are of that kind—earthy contests of old-fashioned pursuits. There are riding, conformation, and performance events, hide-dragging and goat-tying matches, even trotting classes complete with jodhpurs and English saddles. The contests are routinely hilarious, thanks to the animals’ stubborn habit of being stubborn. In every event, without fail, one donkey or mule or another will suddenly refuse to do something it has done a hundred times before—possibly just moments earlier—for no apparent reason. It’s like watching the Ice Capades, waiting for someone to fall.

Except that mules rarely fall, seldom even trip or stumble, and they almost never make a mistake. In two full days of mule events at the Houston Rodeo, encompassing thousands of individual mule attempts at various challenges, there were only three or four failures. But there were hundreds of refusals. And no amount of coaxing or threatening had the slightest effect on a single animal.

The most unlikely event of them all, of course, is the mule jump, based as it is on the human conceit that mules can be induced to leave their feet—all four at once!—springing off the good safe earth and taking flight. By comparison, the goofy California spectacle of frog-jumping seems downright Olympian.

Mules don’t jump the way horses do, loping along at the behest of their rider, blissfully trusting, then leaping pell-mell over walls or fences without a thought as to what might be waiting on the other side. Most mules never would be party to such idiotic adventures. Most mules won’t even approach an obstacle until its rider dismounts and does so first, demonstrating that it’s safe. Then if the mule is interested, it will inch up to examine the situation, peer over the top, and deliberate for a while. Only then, and only if it feels like it, will the mule hop straight up and over, abruptly, with no grace or fanfare, just getting done with it.

Popcorn has already made a dozen jumps today, as the bar climbed higher and five other mules balked. There are only two contestants left, but that fact has no effect on them. Unlike horses, mules will not compete simply for man’s amusement, although they can be taught all kinds of tricks; Popcorn’s elder brother Crackerjack performs a repertoire of about twenty clever stunts. Popcorn doesn’t really give a damn who wins this silly contest.

As preposterous as it sounds, though, mule-jumping can be a meaningful act. It seems that coon hunters following their dogs in southern woods late at night always ride mules. A horse would be impossible, like a motorcycle with no headlights, a nonstop crash. But a mule is fine. The problem is barbed-wire fences in darkest night, deep in the woods. The hunter dismounts, walks to a fence, and throws a blanket over it. Then he tries to sweet-talk his mule into jumping. The success of the hunt depends upon it. So the most successful coon hunters are the men who have earned the confidence of their mules, and they know it. That’s how the competition began.

“Be gentle, look at you,” whispers Red Roper into Popcorn’s floppy foot-long ear. “Be gentle, look at you.”

Popcorn is having none of it. He could jump five six in a heartbeat, sure—personal best is six feet. He’s got nothing to prove. Screw it.

Popcorn steps determinedly outside the dirt square and is disqualified. Red Roper walks over to the winning mule trainer, shakes his hand, and follows Popcorn offstage.

Says Roper: “I guess he didn’t like the ambi-yance.”

- More About:

- Critters

- TM Classics

- Animals

- Houston