This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“Hey, Boss, you got a light?” Every newly hired prison guard, or “new boot,” hears the question. It is seemingly a simple, humble favor asked of men in gray by men in white. The impulse is to accommodate the inmate, since prisons—spiritual wastelands of concrete and metal—cry out for random acts of human kindness.

By the time 21-year-old Luis Sandoval, a new boot at Huntsville’s Ellis I Unit in the summer of 1985, was approached by an inmate with an unlit cigarette, his ears were still ringing from a more desperate request he had heard during his first week on the job. That first week, as he chatted with one of the old boots, the cry came from somewhere behind him: “Help me, Boss!” Turning around, Sandoval saw a Hispanic inmate standing behind a hallway crash-gate, clinging to the bars with both hands. His neck had been slashed; his head was all but severed. A long, metal object—a homemade knife, or shank—protruded from his jugular. The assailant was nowhere in sight.

Sandoval took a step toward the crashgate but was held back by the more experienced guard. “Don’t go in there,” said the veteran, who then correctly hollered, “Fight!” Presently other guards arrived, along with a lieutenant, who ordered, “Open the gate.”

The gate opened. The inmate staggered forward, blood gushing from his head and neck. “Bring a gurney!” called the lieutenant. A gurney was produced, but the inmate ignored it. He continued to walk, step after tortured step, a full fifty yards, before collapsing, dead, in the doorway of the infirmary. Sandoval marveled at the river of red the inmate had left behind.

The brutality of the murder, coupled with Sandoval’s complete inability to prevent it, made quite an impression on the young guard. Nothing during three weeks of by-the-book lectures at the Texas Department of Criminal Justice training academy had prepared him for the helplessness he felt as a lone correctional officer constantly surrounded by violent criminals. It was their house, not his or the state’s. At a given time, Sandoval would stand guard over hundreds of inmates. Anytime they chose—anytime—they could kill him. The thought worked away at his nerves. He took up smoking, two packs every eight-hour shift. The new boot’s new habit, like everything else, was duly noted by the inmates.

“Hey, Boss, you got a light?”

Lighting an inmate’s cigarette is considered an act of friendship or favoritism, and favoritism is forbidden by TDCJ rules. Sandoval knew this. And perhaps he was vaguely aware that the request, if honored, would be only the first of many—that later he would be asked for cigarettes, chewing gum, packs of sunflower seeds, and more. His refusal would prompt the reply, “Then I’ll tell your supervisor about when you lit my cigarette.”

At first the young guard spurned the inmates who pestered him, and threatened to write them up for disciplinary action. But as the weeks rolled on, as the dos and don’ts of the training manual began to look more and more like some bureaucrat’s idea of a joke, his resolve cratered. “It’s a society,” Luis Sandoval told me of the world he inhabited five days a week, eight hours a day. “They have their money. They have their prostitution, their gambling, their extortion. Just like in the free world. It’s a society all its own. And we’re there in it. And as you work there, you tend to become a product of your environment. In a sense, you become a convict also.”

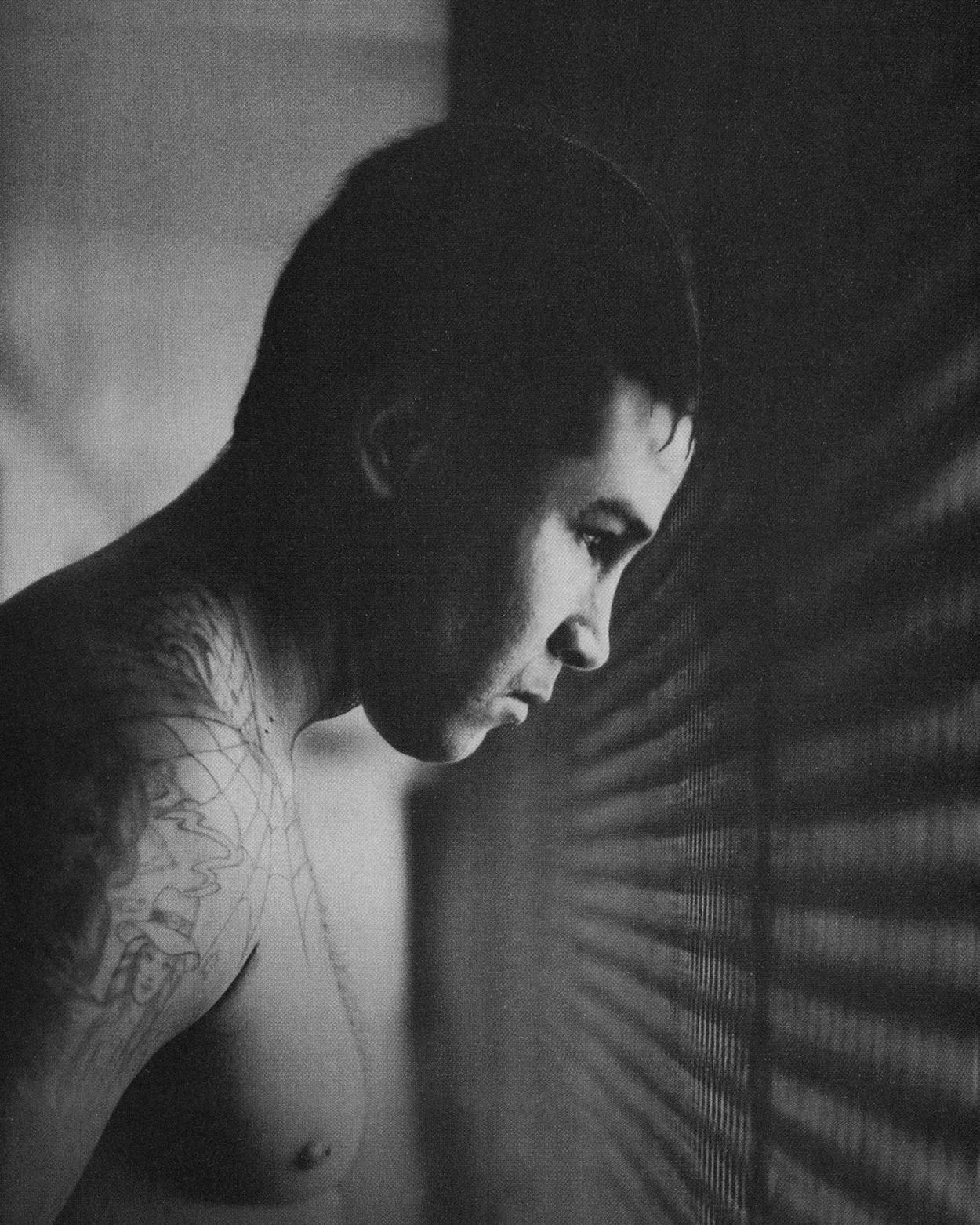

When Sandoval told me that, he was sitting in the interrogation room of the Walker County jail in Huntsville, wearing prison whites. The short, apple-cheeked Hispanic man with the neatly combed hair and the Howdy Doody grin looked too soft to be an inmate or even a guard. Apparently the inmates at Ellis I had noticed this as well, for their sweet talk had gotten to him. Over time, Sandoval got sucked into the undertow of prison life. He lit cigarettes, which led to other small favors, which led to bigger ones. In his first year on the job, Luis Sandoval found himself delivering drugs to a self-described drug runner on behalf of the state’s deadliest prison gang, the Texas Syndicate. Two years after lighting his first cigarette, Sandoval was arrested and charged with murder for allegedly aiding a gang plot to kill an inmate.

Now it was May 1991, and Sandoval was behind bars, his fate in the hands of a Huntsville jury. The first Texas prison guard ever to be tried for the murder of an inmate seemed eager to describe, to me and to the jurors, the pressures and temptations a correctional officer faces. “I was a damn good officer,” he told both me and them. But he also acknowledged that he had made mistakes; and to me, though not to the jury, he confessed that one of those mistakes was bringing drugs into Ellis I. (After the trial, Sandoval became less talkative on the subject of drugs. Several weeks after the jury’s verdict, he told me over the phone that he wished to recant everything he had said to me on tape about his involvement with drugs.)

The Sandoval trial was a rare public washing of the Texas penal system’s bloodstained linen. It revealed a world where drugs and weapons are freely available to inmates, where murderous prison gangs control inmate behavior far more than prison guards do, and where the guardians of law and order have just as much trouble distinguishing right from wrong as do the inmates they are watching. The prosecutors of Luis Sandoval not only conceded this but went out of their way to make it part of their case. “If you work at any time for the TDCJ,” said assistant prosecutor Burt Neal “Tuck” Tucker during the first day of testimony, “you know how powerful the Texas Syndicate can be.”

With the impersonal manner of assassins who have long since become intimate with the odor of death, the witnesses—guards, inmates, and prison officials—readily supplied evidence that gangs are calling the shots in our prisons. A host of documents relating to the trial, as well as interviews with numerous sources involved in the case, have provided chilling details of how Texas prisons really work today. To the public, the saga of Luis Sandoval will be a shocking revelation of how Texas prisons have spawned an organized crime wave that afflicts the entire state. But to prison officials, the story is as familiar as the smell of marijuana in a cellblock and the sight of an inmate with a hand-tooled shank.

A Fly in the Salt Shaker

“Who’s on trial here, Louie?” demanded the intense and steely-eyed chief prosecutor, Travis McDonald, during his two-hour grilling of Luis Sandoval on May 24, 1991. “Are you on trial or is TDC on trial?”

“I’m on trial, sir,” conceded the polite young man in the pin-striped suit who sat in the witness stand. But the defendant’s earnest tone suggested that this was itself an injustice—that the prison system had asked the impossible of prison guards and was now punishing Sandoval for the state’s shortcomings. The only witnesses who said that Sandoval had anything to do with the murder of inmate Joe Arredondo were two convicted felons: Carlos Rosas, a Texas Syndicate member who confessed to actually stabbing Arredondo but was offered a favorable deal in exchange for his testimony; and Ruben Ortiz, a convicted murderer and Texas Syndicate sex slave who was paroled after he agreed to testify.

Ten Ellis I guards who worked with Sandoval testified that they had no knowledge that Sandoval was involved in drug transactions with prison gangs. Nearly all of them, however, confessed that they knew TDCJ had its share of dirty guards. Sandoval is one of more than sixty TDCJ guards who have been indicted by McDonald’s Special Prison Prosecution Unit over the past six years for felony offenses. That statistic does not come close to reflecting the actual number of TDCJ employees suspected of involvement in corrupt activities. The real picture presents gloomy evidence of who really is in charge at TDCJ—not the state, not the guards, but the convicts themselves.

Unlike most state crises, there is absolutely no mystery to the takeover of our prisons by violent gangs. Virtually everyone saw it coming. The ink from U.S. district judge William Wayne Justice’s signature on his 1980 Ruiz v. Estelle decree had not yet dried before critics were predicting that the prison reforms specified in the judge’s order would leave a dangerous power vacuum.

Until Judge Justice’s decree, TDCJ’s inmate population was essentially governed by brutal trusties known as building tenders, whose methods—which included beating and sodomizing inmates into terrified submission—went largely unchecked by prison officials. Everyone agreed that the building tender system was a cheap and crudely effective method of maintaining order. But the evidence gathered by Justice clearly added up to a violation of the Eighth Amendment’s protection from cruel and unusual punishment. Justice therefore ordered that the two thousand building tenders be replaced by more prison guards, who would police the inmates with a firm but civilized hand.

The guards were hired. But they weren’t enough: A guard like Luis Sandoval would be assigned to a hallway filled with hundreds of inmates. “They’re coming in from work, they’re coming out of the tanks to go eat or recreate or go to school or go to the chapel,” said Sandoval. “And all you see is white shirts. It’s like a fly in a salt shaker.”

Today the numbers still favor the inmates: There are 47,751 of them and only 3,500 security personnel—none of whom carries a gun—per eight-hour shift. At the close of the eighth hour, the shift changes, but the inmates remain. “In your house you can walk around in the dark and not bang your shins because you know every square inch,” said a former Ellis I officer. “Well, so does the inmate. After you sit there for twenty-four hours a day with nothing else to do, you discover all sorts of good hiding places.” Added a current officer, “The only time that we can find drugs is if an inmate snitches and tells us.”

Inmates know their surroundings, and they know that the surroundings are theirs. And as in any society, some lead while others are led. We in the free world classify inmates according to motivation: those who do not wish to live a life of crime and those who know no other life; those who wish only to do their time and get out and those who function best in a kill-or-be-killed environment. As the free world would have it, there are good inmates and bad inmates. But such sentiments are meaningless down on the farm. There are only weak inmates and strong inmates.

Prisoners join gangs, thereby becoming strong, and prey upon the weak. The first major TDCJ gang, a Hispanic group known as the Texans, consisted of former residents who were doing time in California penal institutions in the mid-seventies. To defend themselves against harassment and assault by California prison gangs, they formed their own protection group. Push inevitably came to shove: In two separate gang confrontations, the Texans murdered one California inmate and seriously wounded another. Word spread that the Texans were a force to contend with. Upon their release from prison, gang members returned to Texas, renamed themselves the Texas Syndicate (TS), committed crimes, and wound up in TDCJ, where they developed an extensive network of drug trafficking, extortion, prostitution, and contract murder behind Texas prison walls.

Other inmates reacted to the TS as the TS members had first responded to California gang harassment. Hispanics who were not TS members formed their own gang, the Mexican Mafia, which today outnumbers the TS two to one but is not considered as well organized by prison officials. (Officials also say the Texas Syndicate is far more selective and does not, for example, recruit homosexuals.) Meanwhile, white inmates, tired of being robbed and sexually assaulted by the larger population of black inmates, began the Aryan Brotherhood of Texas. The blacks, in turn, formed the Mandingo Warriors. Other gangs also sprang up: the Hermanos de Pistoleros, the Self-Defense Family, the Texas Mafia, the Nuestra Carnales. Each gang had its own hierarchy and its own rules; each member was not permitted to leave his gang, even outside of prison, except by his own death. And each gang, after accomplishing the first objective of protection from other gangs, preyed on inmates who would buy drugs or sex or who could be intimidated into giving sex or buying protection.

Throughout the Sandoval trial, guards on the witness stand were asked if they had ever stopped a gang member from murdering an inmate. The answer was always no said former Ellis I officer Nolan McCool, “If the opportunity exists, they’re gonna make the hit. If you tell him, ‘Put that knife down,’ he’ll look up at you and say, ‘I ain’t through yet.’ These people are serious. If they don’t make this hit, they’ll become the person to get hit. So it may be a week or a month or a year . . . but that hit is on.”

Today supervisors advise guards: “We cannot stop a hit. So don’t try.” Guards have been instructed to monitor gang activity but have shown an embarrassing inability to do so. At the Ferguson Unit, for example, guards wore special caps sporting a patch designed by an inmate. It took months before someone looked closely at the gas mask featured on the patch and realized that every correctional officer at the unit had been wearing the letters TS across his forehead.

Gangs didn’t worry about guards; they worried about each other. The field for their activities, though fertile, was finite, thus making turf wars inevitable. During August and September of 1985, a long-standing rivalry between the Mexican Mafia and the TS exploded into a free-for-all throughout the prison system, leaving eleven inmates dead. For about three months thereafter, while state officials sought a long-term solution, every prison unit experienced a total lockdown. Every inmate was confined to his cell, stripped of recreation and visitation privileges, and fed sandwiches that guards tossed through the bars of the cell. By the spring of 1986, prison officials had examined every inmate for telltale tattoos, weeded out identifiable gang members, and ordered that they spend the rest of their sentences in administrative segregation, away from the general population.

After the lockdown, the murder rate plunged. Peaceable inmates who had lost faith in TDCJ’s ability to protect them now felt less inclined to carry shanks everywhere they went. A certain order prevailed, which stilled the critics and deflected the interest of the media. Prison officials could boast that their residents stood less chance of being killed than did the average Texas city dweller. By the end of the eighties, the public fretting over prison gangs had dissipated.

But the sudden absence of gang wars did not mean that the gangs had gone away. On the fourth day of the Sandoval trial, as if to punctuate the implicit warning in the testimony that gangs till thrived within the system, a member of the Mexican Mafia stabbed a Hermano de Pistolero to death at the Eastham Unit. Around the same time, prison officials expressed concern about the fifty or sixty members of the two Los Angeles–based black street gangs, the Bloods and the Crips, that had recently entered the system. The youth gangs haven’t caused trouble yet, but the realities of prison life suggest that this will surely change.

The Bloods and the Crips will likely adapt to their new environment just as other inmates do. To make identification difficult for prison officials, most gang members no longer wear tattoos. Uneasy truces between gangs have developed. The 1,577 gang members currently housed in administrative segregation represent only a fraction of those inmates who actually do the gangs’ bidding. Many of the gang leaders who had been doing time are now in the free world, spreading the gang network across the state, beyond prison walls. TDCJ intelligence files indicate that by the close of the eighties, the TS, the Mexican Mafia, and other prison gangs had developed active memberships in every major Texas city, as well as in several small towns. Our prisons, far from turning out reformed citizens, have instead become incubators of a statewide crime wave.

The gang murders that once took place inside prisons now take place on the streets. Prison officials believe that the rivalry between the TS and the Mexican Mafia has produced homicides in Austin, Dallas, Houston, El Paso, and especially San Antonio, where nearly one hundred suspected prison-gang-related murders were committed last year. This past May, the bullet-riddled body of Mexican Mafia member Andres Sampyro was found in a San Antonio barrio.

What sustains the gangs is money, which inmates use to bribe prison employees. The money chiefly comes from drugs. Drugs come from the free world. Prisons, crammed with thrill-seekers and outright junkies, provide the ultimate captive consumers. Each society sustains the other, but the economic cycle depends on a vital link, for the supply will not meet the demand unless the product reaches the consumer. To get drugs out of the free world and into prison cells, there must be a courier. And the courier must possess a particular power: He must be able to walk through walls.

A Call From El Carpintero

“Hey, boss, you got a light?” Luis Sandoval pulled out his lighter and, as he had before, lit the cigarette held by Armando Garcia. (This inmate’s name has been changed as a condition of his interview.) Garcia, a four-time loser serving a life sentence for repeated theft and heroin offenses, was one of the friendlier inmates: 33 years old but actually grandfatherly in demeanor—a gentleman, you could almost say—quiet and unthreatening. And Sandoval welcomed his company.

Sandoval felt more at home with fellow Hispanics than with the black inmates, who terrified him. The five-foot-six, soft-voiced young man had spent most of his life in the South Texas town of Alice, where blacks were scarcely seen. His mother and stepfather lived in a middle-class neighborhood, but most of Sandoval’s friends lived in the barrios or in the projects of Kingsville, where Sandoval attended college for three years. In the tenements across the street from the Texas A&I University stadium lived a fifteen-year-old girl named Veronica, whom he married on June 22, 1985, after learning that TDCJ had accepted his application for employment as a correctional officer, or CO. The next day, a Sunday, the newlyweds threw their possessions into a suitcase and a grocery bag, and drove Sandoval’s Datsun to Conroe. On Monday, at eight in the morning, Sandoval reported for duty at the Ellis I training academy in Huntsville.

“I’ve seen about five new boots take one step out of the control riot-gate and into the main hallway and turn around and say, ‘See you later,’ ” said Sandoval. “If you last six months in there, you’ll make it. But the first six months is hell.” Sandoval was determined to tough it out. The new boot suffered the usual abuse from veterans and inmates. But he stayed out of trouble, in large part because of two hall porters, Bubba Ray Smith and Johnny Abrams. The two inmates snitched for Sandoval and herded him away from troublemakers, admonishing him, “Boss, stay away from those guys.”

Somehow an inmate by the name of Vicente had gotten past the new boot’s boys. Perhaps it was because Vicente was so quiet and servile or perhaps he had such a talent for lingering that the porters simply paid him no mind. It seemed that everywhere Sandoval went, there was Vicente, pushing his broom across the floor, sometimes waving or offering a greeting to the new boot, but never badgering him. Eventually the guard found himself engaging in polite conversation with the inmate. Sandoval came to enjoy these moments. It was a pleasure to deal with an inmate man to man, for once. When Vicente and his friend Armando Garcia—also a pleasant, nonconfrontational fellow—began to ask Sandoval if he had a light, the guard refused at first, and finally decided, after repeated requests, what the hell. Some rules were just too silly to heed.

Eventually, however, Vicente and Garcia began to ask for more than a light. The inmates handed Sandoval a letter, wondering if the guard could mail it for them. “I don’t have any money to get any stamps,” Garcia explained.

Sandoval weighed his choices. If he refused to do the favor, they could always snitch on him for lighting an inmate’s cigarette—though Sandoval didn’t think either was that type of inmate. On the other hand, if his superiors caught him delivering inmate mail, they could fire him on the spot. But that was if they caught him. Or if they cared to enforce the rule. Neither possibility seemed likely, given what Sandoval had learned about TDCJ in his first few months on the job.

At Ellis I, Sandoval had never seen so many rules enforced so haphazardly. Homosexuality was prohibited, yet punks strutted about in their cells, wearing women’s panties and makeup. Alcohol was forbidden, yet “chock,” or homemade wine, was made in a variety of ways in cells, the crudest method being by letting food wrapped in a plastic bag fester in a toilet tank. One Ellis I officer reported that in 1986, between one hundred and two hundred gallons of chock was discovered on a weekly basis within the unit.

Compared with Luis Sandoval’s quiet life in Alice, Ellis I must have seemed like an opium den. The 1985 lockdown put a damper on the atmosphere but not on the flow of drugs. Guards could still smell burning marijuana and still see inmates giggling to themselves.

Inmates fashioned shanks out of road signs, door hinges, food trays, typewriter platen rods, and field equipment. After the big lockdown, metal detectors were installed in every prison unit to discourage the carrying of shanks. Thereafter, inmates made their blades out of hard plastic or made do with whatever crude instrument was within reach, like the cast-iron weight an inmate found in the recreation yard and used, with one vicious swing, to lop off the ear of another inmate. Other weapons were by-products of inmate ingenuity, as in the case of Cosmo, the death row inmate who fashioned a bomb out of matchstick tips and an asthma inhaler and blew a hole in his cell wall.

Though inmates weren’t allowed needles for tattooing, resident artists took to using the metal pieces of windup toys. Convicts made primitive ovens out of foil-lined cardboard boxes equipped with a light bulb, and cooked deer or rabbit killed by inmates working in the fields. Sandoval caught one inmate with a homemade oven and a laundry basket filled with about fifty prime-cut steaks.

The steaks would have come from the kitchen; the laundry basket that held them would have been wheeled past a guard. Either the guard didn’t know what was going on, or he did. Sandoval figured the odds were about even. In prison, he had come to learn, if you gave, you got. Rumor had it that inmate Jesse Turner had stood between an inmate and a prison official and had taken the blade himself. Now Turner could be seen pushing trash cans down the hall, twirling his knife in the air; nobody took his knife away. According to Sandoval, Howard Digby, a runty burglar with a pug nose and heavily tattooed arms, was known as a captain’s boy, a snitch who filled his boss’s cup with coffee and his ear with prison gossip. In return, the snitch had an oversized cell to himself, plus a hall pass that gave him the run of the unit.

Sandoval did not know any warden, ranking officer, or CO at Ellis I who did not have at least one snitch. Everyone wanted information—on the inmates, on their superiors, on their peers. Seemingly everyone in Ellis I would snitch or be snitched on. If you didn’t treat your snitch right, he would scurry off to a more grateful listener and begin his new relationship by snitching on you. It was not the most hospitable climate for trust, which was something Sandoval felt inclined to consider when Armando Garcia and Vicente held out a letter and asked Sandoval to mail it for them.

Today, Sandoval says he mailed the letter and others like it “with a kind heart but with bad judgment.” And in an institution where judgment allowed some inmates to flaunt dangerous weapons while officials looked the other way, mailing the letter seemed like a minor transgression. He did so and, he told me, was then given $50 by the inmates. Later, Vicente asked the guard if a free world individual could mail Sandoval two money orders, which Sandoval would cash and then bring the $250 to the inmates. Sandoval did as he was asked. For his trouble, the inmates offered the guard $75. Sandoval told me that he took the money, though he denied it in court. Later, when Vicente asked the guard to phone a number in Brady and ask the person who answered when Vicente’s family would make their next visit, Sandoval had no objections. On another occasion, Vicente asked Sandoval to deliver the phone message that Vicente needed money to buy arts and crafts supplies. The guard made the call, apparently unaware that such messages, and the letters, might contain coded instructions from a prison drug-runner to a high-ranking member of the Texas Syndicate.

Garcia himself was not a TS member. Murder wasn’t his thing. He was a drug dealer, with connections dating back to his days peddling heroin in El Paso. Like any good businessman, Garcia kept a close eye on the marketplace. When cocaine was cheap, he sold coke; when pure coke became scarce and heroin became abundant, Garcia seized the opportunity. “I just want to take care of my business,” he would tell gang members who tried to recruit him. A deal was struck between the gang and Garcia: Garcia would acquire the drugs, give half to the Texas Syndicate, and sell the other half himself. All Garcia and his friend Vicente lacked was a reliable “drug mule” who could be counted on to transport drugs into the prison.

Eventually, Sandoval agreed to bring drugs into Ellis I. The drug trade was lucrative, and Sandoval always seemed to be hurting for money. But other factors have caused guards to agree to be drug mules. One of them is fear. The moment Garcia asked Sandoval to bring marijuana into TDCJ, it did not take superhuman deductive powers for the guard to figure out the Hispanic inmate’s clientele. Recalling the letter deliveries and phone messages, Sandoval might have wondered just what he had gotten himself into and how deeply. Garcia, of course, could snitch to the Ellis I authorities. But now that seemed the least of Luis Sandoval’s worries.

The other factor that has led guards to traffic in drugs is the peculiar morality of Ellis I, where rules are never universally applied and the use of drugs is so widespread that officials have to know—and accept—that prison guards are involved in the supply chain. On Sandoval’s shift alone, at least four or five guards had been busted for bringing drugs into prison, but there were others who hadn’t been busted and probably never would be. One was an officer who muled marijuana and cocaine for a black inmate known as Apple Jack, whose activities were no secret at the unit. “He would stand at the searcher’s desk like he was running the building,” Sandoval said. “Everybody knew about this scum.” Yet Apple Jack went unpunished: He tithed a share of his profits to the Texas Syndicate and gave the supervisors something to crow about by setting up a guard now and then. Apple Jack protected his mule, however, and though many knew of the officer’s extracurriculars, the hammer never fell on him.

One day Garcia told Sandoval to expect a call at home that evening. The caller, known as El Carpintero, was a convicted child molester from El Paso who nonetheless had managed to obtain a job, under an assumed name, as an x-ray technician at Ellis I. El Carpintero instructed Sandoval to drive to a location in Huntsville where a sack containing marijuana awaited. Sandoval picked up the marijuana and smuggled it into Ellis I—frightened every step of the way, he told me, that someone might notice the smell of marijuana and search him. But no one suspected a thing.

After that first transaction, Sandoval went back for more—a total of “three, four, or five times,” he told me, though he vividly described six transactions to an investigator hired by his family. (For that matter, Garcia testified during the trial, outside the presence of the jury, that Sandoval muled drugs “countless times.”) Sandoval was never searched, he told me, and came to learn that “the only way they bust you is if they’re told by a snitch, ‘This guy’s coming in today.’ ”

While Sandoval said there were other guards—and even supervisors—involved in drug activity, the Texas Syndicate preferred that Garcia deal directly with Sandoval, a fellow Hispanic. Sandoval’s apparent relationship with the gang did not escape the attention of the Ellis I population. “I’d say about eighty percent of the inmates knew he was dealing,” claimed one inmate who was close to the action. “They’d say, ‘Don’t mess with him.’ ”

The new boot thereby became a feared boss among bosses. To the newer guards, Sandoval’s stature among the inmates was something to behold. “Sandoval was one of the officers I wanted to be like,” said one correctional officer whom Sandoval helped train. “I could watch him deal with inmates and think, ‘This guy knows something I don’t know.’ ”

One evening, while gazing out from his apartment balcony, Sandoval saw a car drive slowly by. Paranoia overcame him. He grabbed the stash of marijuana he had recently picked up, ran to the bathroom, and flushed it down his toilet. “Look, man, I think I’m being watched,” Sandoval told Garcia the next day. “Armando, I can’t jeopardize my life, man.”

Garcia took the story to the Texas Syndicate. They didn’t believe Sandoval. The mule, they believed, had done the drugs himself. Either way, Sandoval was out. The next day, Sandoval recalled, “I walked into work feeling good. I had the burden lifted from my shoulders.”

The Hit

“You have these inmates,” said an Ellis I correctional officer, “where you write ’em up [for rule infractions] and nothing happens. Rank is taking care of them.”

Joe Arredondo was one of those inmates, an arrogant squirt barely over five feet tall who frequently provoked guards but never got in trouble for it. In fact, his disciplinary record was almost spotless, and he enjoyed the privileged position of commissary clerk.

By the fall of 1986, several months after the gang lockdown policy had been instituted, Joe Arredondo’s cockiness began to catch up with him. Arredondo was a Texas Syndicate member. He had been ordered to carry out a hit on another inmate and had failed to do so. Arredondo did take part in a different contract killing, but when all the conspirators except Arredondo were placed in administrative segregation, TS members concluded that Arredondo had snitched on the rest to save himself. The decision was reached: Arredondo would be taken down. The question was when. He had a one-week prison furlough coming up; the gang didn’t want to spook him, fearing that he might not return to Ellis I. To keep him at ease, the Texas Syndicate requested that the inmate return from his furlough with two hundred dollars’ worth of heroin and marijuana. Arredondo took the two hundred dollars, went home, and blew the money.

Ellis I officials caught wind of the deal through a snitch. Upon Arredondo’s return, they ushered the inmate to an infirmary cell, where a guard stood nearby, waiting for Arredondo’s bowels to evacuate a container of drugs. But Arredondo had brought back nothing. Word spread through the unit the way it always had, at bewildering speed: Joe Arredondo was a dead man.

The roles in the Arredondo hit were decided in either the chow hall or the chapel, where numbers were drawn from a cup. According to testimony, the man who drew the magic card, number one, was TS sergeant Carlos Rosas, a 31-year-old Dallas resident who was serving thirty years for aggravated robbery. Rosas would do the killing, while another TS member held Arredondo and two others stood by as lookouts. The murder would take place in a corridor abutting the B-wing: the maximum-security area where Luis Sandoval often worked.

The B-wing, a loud and grossly overcrowded area, “was considered the hellhole,” in the words of Cade Crippin, the CO who worked the B-wing with Sandoval the afternoon of the murder. Some of the state’s most violent criminals were housed there. At certain times, more than five hundred of them might flood the B-wing hallway en route to the gym, the chapel, the woodshop, or the chow hall. When asked on the witness stand if the hallway was ever undermanned, the reply of Nolan McCool—another officer working the B-wing that afternoon—was emphatic: “Constantly.”

Conditions were no different on December 17, 1986, which was why Sandoval was given the assignment of B-wing hall boss that afternoon. He had long since survived the new boots’ six months of hell. By now he was a CO III, an old boot, and he had trained many of the guards who now worked with him. His assignment was one of the toughest jobs in Ellis I. The west end of the B-wing hallway was left unguarded after three-thirty every afternoon, when the guard normally stationed there was transferred to the chow hall. This practice violated the Ruiz stipulation that an officer must be present at all times at any entrance or exit of the main building. It was also a dangerous practice in light of the fact that a narrow corridor intersected the west end of the B-wing and only an officer standing at that end could see what was going on in the corridor.

But Ellis I officials, like so many other wardens in the post-Ruiz era, were playing a numbers game. Chow time meant that vast numbers of inmates would be crowded together in one room. Extra guards to supervise the gathering had to come from some other post. Officials knew this meant that every day from three-thirty until after chow time, activities in the narrow corridor went unmonitored. It was a blind spot, and unit officials hoped the inmates wouldn’t notice. But according to one Ellis I officer, “Inmates watch everything we do. That’s all they do—look for our weaknesses.”

At about five-thirty that afternoon, Sandoval approached CO II Cade Crippin, who was inside a cellblock, observing the inmates. “Take over the hallway for me,” Sandoval said to his subordinate while handing him his keys. Then he headed for the bathroom, a route that took him through a confined area guarded by CO II Nolan McCool. McCool opened the picket gate to allow Sandoval into the rest room. Just as he entered, Sandoval heard someone yell, “He’s on the floor! He’s bleeding!” He whirled and burst into the B-wing hallway. Looking toward the chapel, he could see Crippin ahead of him, heading for the hidden narrow corridor at the west end of the B-wing.

When they got there they found Joe Arredondo lying on his back. Blood was gushing out of a hole in his neck; he was unconscious but gasping wildly. An eight-inch metal shank lay nearby. Sandoval put his hand against the wound, looked up, and saw Crippin and McCool standing there, gaping. “Yell ‘fight,’ ” he said, but the two officers seemed paralyzed. Sandoval got up, ran into the hallway, and yelled “fight” twice. Then he returned to Arredondo. “Give me your shirt,” he ordered an inmate and with it applied pressure to the wound. Crippin knelt and lifted the inmate’s legs. “Leave them on the floor!” said Sandoval. “You’ll drain all the blood to his head.” Three other officers arrived on the scene. “Get these inmates in the chapel,” he told them. “And call for a gurney.”

Joe Arredondo was taken to a hospital in Huntsville. He was pronounced dead at seven that evening, a victim of twenty stab wounds. By that time, things were quiet again at Ellis I. There was no further violence, a signal to those who understood gang behavior that Arredondo had been snuffed out by one of his own rather than by a rival gang. The following day, Chaplain Alexander Taylor, who witnessed Sandoval’s efforts, wrote the CO III a letter of commendation. That afternoon, Ellis I warden Jerry Peterson called Sandoval into his office to congratulate him on a fine job. The warden would later testify that Sandoval’s actions were “somewhat heroic.” But, Peterson added, the hero had seemed awfully calm in the midst of all the bloodshed—perhaps too calm.

On a Westbound Bus

Ten months after the murder, on October 23, 1987, Sandoval was again summoned to the warden’s office. This time, however, four Internal Affairs officers greeted him inside by reading him his rights and charging him with murder. He was accused of leaving a door unsecured and unguarded as part of a murder plot. Sandoval was then ordered to take off his uniform and replace it with inmate furlough clothes. The officials fitted Sandoval with handcuffs, leg irons, and a belly chain. He was whisked off to the Walker County jail.

That afternoon in the interrogation room, Special Prison Prosecution Unit investigator Royce Smithey bore down on Sandoval. You were in the hallway, Smithey said. A man was stabbed twenty times. Whoever killed him had to have come through the B-wing hallway and had to have been dripping with blood. You’re telling us you saw nothing? You’re telling us it’s a coincidence that you weren’t down at the end of the hallway? Come on, Sandoval. We know who you’re tied to. We know who you take orders from.

Sandoval insisted that he didn’t know anything about the Arredondo murder other than what he filed in his report. The guard said he wasn’t tied to anyone. But things got more interesting when Internal Affairs investigator Dale Schaper walked into the room and handed Sandoval copies of his phone records, showing that 25 phone calls he had made on Vicente’s behalf were to a high-ranking TS official named Felix Benavidez.

Sandoval buckled. Yes, he had made the phone calls. Yes, he had mailed Vicente’s letters, had cashed two money orders for the inmate, and on three different occasions, had delivered packages from a parking lot to a telephone booth. The packages, he admitted, most likely contained drugs. Dale Schaper dutifully typed up his report, and sent it through the proper channels. (Today, Sandoval says that statement was coerced.) Six weeks later, in December 1987, Luis Sandoval was terminated from the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

It took more than three years for the Arredondo murder case to come to trial, during which time a number of things happened to Sandoval. His wife divorced him. His father died. He was arrested for driving while intoxicated, following a one-car accident that left his limbs temporarily paralyzed. To pay for his legal expenses, his mother sold the family home. Sandoval, in the meantime, worked at J.C. Penney in Plano.

One day Sandoval received a phone call at work. The caller advised Sandoval not to show up for his March 18, 1991, trial, and then hung up without identifying himself. On the witness stand, Sandoval suggested that the caller was someone from TDCJ Internal Affairs; more likely, he was a Texas Syndicate member delivering the message that the TS would not be amused if Sandoval blew the whistle on their activities. Even before the call, Luis Sandoval had been sweating bullets. Armando Garcia had seen this coming. Garcia would later say that he told Sandoval shortly after the Arredondo murder, “Man, you’re in deep shit. They’re gonna be looking at you, and all that stuff in the past is gonna come up. They’re gonna say you were in on it. You better get the hell out of here, Sandoval.”

Sandoval took the advice three years after Garcia gave it. On March 19, the name of Luis Sandoval was called three times in the Walker County courthouse, but the defendant did not respond. He was on a westbound bus, fleeing the state. Sandoval got off in Los Angeles and found his way to Van Nuys, where a cousin put him up in his apartment. For several days, Sandoval read the Bible and considered his options. He called his mother, who begged him to turn himself in. He told her that he feared the Texas prison authorities, who by now had surely discovered that the murder of Joe Arredondo was, if anything, a result of prison mismanagement. It was their fault, not his, but someone would have to take the fall. Sandoval did not tell his mother why he was such a vulnerable candidate.

He did not turn himself in. Instead, he wrote an impassioned, handwritten 24-page letter that his mother sent to a few members of the media. The letter was not what one might expect from a former prison guard. It criticized TDCJ’s good ol’ boy system, which Sandoval claimed “has ruled with an iron fist since the penal system was first established.” Hispanic guards, he said, were “either coerced into quitting or found doing something wrong.” Supervisors treated inmates “like animals.” He further wrote, “I am not the only one who worked there that knows that TDCJ is linked to the gangs and their illegal activities. Inside the walls of each prison is drugs, prostitution, gambling, extortion, and grand theft, but no investigation into any of these things has ever been made.” The letter did not say what such an investigation would say about Luis Sandoval.

When he sent the letter off to his mother, he knew it wouldn’t be long before law enforcement officials discovered his whereabouts. With what was left of his final J.C. Penney paycheck, Sandoval and his cousin drove to Las Vegas, a place Sandoval had always yearned to visit. They blew the paycheck on the slot machines; they had a wonderful time. On the way home Sandoval asked his cousin to drive the scenic route. “I want to see the mountains,” he said.

A few days later, on April 12, 1991, FBI agents showed up at the apartment where Sandoval had been hiding and took him to the Los Angeles County jail. Twelve days later, Texas chief prison prosecutor Travis McDonald flew to L.A., took custody of Sandoval, and flew him back to Huntsville, where he was held without bond at the Walker County jail.

Not Guilty

For all of Sandoval’s claims that the system was making a sacrificial lamb out of him, the system came to his rescue in the end.

The two inmate snitches who testified against Sandoval understated their criminal history, contradicted each other, and came off looking like dirtbags who would say anything for the right price. In contrast, sixteen current or former Ellis I employees testified. Not one of them pinned the murder of Joe Arredondo on Sandoval. Not one of them said that Sandoval was a bad officer; many, in fact, went out of their way to laud his abilities. Several of them testified vigorously that Ellis I was understaffed and overcrowded, and that the unit was riddled with blind spots.

None of them knew anything about Sandoval and drugs. Asked point-blank by his attorney, Did you ever bring drugs inside TDCJ? Sandoval lied: “No, sir.” Contradicting this claim, Internal Affairs investigator Dale Schaper took the stand and read his report of the night Sandoval was arrested. But the report was not a signed confession. When asked about it, Sandoval testified that the report merely contained Schaper’s accusations, which Sandoval denied then and would deny now, under oath. Had Schaper’s investigation been thorough, this denial might have seemed implausible to the jury. But the report made no mention of Armando Garcia and El Carpintero; nor did it offer any evidence that Sandoval had actually smuggled drugs into Ellis I.

It took the jury 33 minutes to decide that Sandoval was not guilty. After their verdict was announced on Wednesday, May 29, the jurors milled around outside the courtroom and vented their disgust with the state’s case to the media. One juror phoned Sandoval’s brother that afternoon and told him that in her view the case against Sandoval was racially motivated. A week later another juror wrote Sandoval a four-page letter, expressing her chagrin that he had been put through all the agony.

Not everyone was so sympathetic, however. After the trial, Sandoval’s attorney, Steve Fischer, contacted TDCJ officials and asked them to let bygones be bygones. “Louie would love nothing more than to be a guard again,” Fischer told them. The attorney was advised that his client would never again wear gray in a state penal institution.

Were he to pay his old workplace a visit, Luis Sandoval would notice several changes at Ellis I. Video cameras monitor the hallways. The corridor where Joe Arredondo was murdered is now permanently guarded. Beneath the cosmetic alterations, however, things at Ellis I are just as Sandoval left them. On August 26, 1990, a death row inmate proved his loyalty to the Aryan Brotherhood during his daily recreation hour by strangling a black inmate in a recreation yard with a jump rope while the latter was performing oral sex on the former. And in March 1991, McDonald’s prosecution force indicted yet another Ellis I guard. “He was muling,” said McDonald.

Sandoval described Ellis I warden Jerry Peterson as “a good man but a figurehead. His assistant wardens run the building.” Indeed, Peterson said to me that his unit’s drug problem “isn’t rampant,” but he also acknowledged that much has escaped his attention over the years. Even after Arredondo’s murder, when the Special Prison Prosecution Unit began to gather incriminating evidence against Sandoval, Peterson showed little interest in the details. “The investigators didn’t tell me much, nor was I particularly inquisitive,” he said.

Gangs still terrorize the prisons. “There’s no way to shut them down,” Sandoval said. Yet a former prison drug-runner confirmed the obvious—that without the help of TDCJ employees, the flow of drugs into state prisons would dry up. Without drugs, gangs would have little income; without income, they would have little power over the system. But the system will not change. Employees come and go unfrisked, unobserved. The system snitches on one mule while protecting another. “And there’s always somebody,” the ex–drug runner told me, “who’ll do something for you.”

“I didn’t do it,” Sandoval announced to me in a recent phone conversation. Reminded that our earlier on-the-record, on-tape conversation contradicted this, he said, “I have my life to think about. . . . I made my mistakes. But I was a good officer.” Thus, the former good officer now wished to disavow everything he had told me earlier. As to everything he had told his investigators—none of that was true either, he said. He had lied to his own investigator, just as inmates and Internal Affairs had lied to the jurors. No one, he seemed to be suggesting, was capable of telling the truth about Luis Sandoval—not even Sandoval himself.

A Good Kid

The inmate, a former gang operative now in protective custody, pulled a hand-rolled cigarette out of his white shirt and lit it. He squinted through the smoke and the bars and the memories. “I can’t honestly tell you why he did it,” said the inmate of Sandoval. “There were many times when he said, ‘I ain’t gonna do this shit anymore.’ And we’d think, well, maybe we’re putting too much pressure on him. So we’d just lay back, let him cool down. Then he’d say, ‘Damn, I wish I had twenty dollars to go buy a couple of beers.’ And I’d say, ‘Just wait here, I’ll be back.’ And I’d collect fifty dollars for him. Then he’d have to do something for us.

“When Arredondo got killed, Sandoval was just in the wrong place at the wrong time. If the Texas Syndicate had told him there was a murder happening, he wouldn’t have gone for it. I remember when he yelled fight. I was in the dayroom. I looked up and as he was running by, he looked at me . . . like he wanted to cry, you know? I knew he didn’t have nothing to do with it.

“Sandoval, he was a good kid,” said the inmate of the guard who had once done him favors. “He just got involved with the wrong people.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Prisons

- Longreads

- Crime

- Huntsville