After the home team wins a big game, fans are likely to say, “We beat the [bleep] out of those [bleep]!” But the coach takes a more elliptical approach. He runs away from definitive statements the way a running back avoids a linebacker. After a victory, a coach might say, “We put ourselves in a position to win.” Or, “I saw a lot of good things out there tonight.” Or simply, “Good stuff.” Coachspeak does not stoop to dignify the drama or complexity of the game, and a reporter who happened to miss it shouldn’t be able to tell by the press conference whether the team won or lost.

Lately, I’ve been admiring the work of three Metroplex-based kings of coachspeak: Avery Johnson, who until May was the head coach of the Dallas Mavericks; Ron Washington, of the Texas Rangers; and Wade Phillips, of the Dallas Cowboys. These men aren’t great coaches by any stretch. But their contributions to coachspeak are worthy of the Hall of Fame. Follow along, if you can, as we admire their handiwork.

Johnson was fired after the Mavericks lost in the first round of the NBA playoffs (again). The sportswriters wanted him to come clean with his frustrations about the Mavericks’ midseason point-guard swap of Devin Harris for Jason Kidd, but Johnson was too savvy for that. “That trade was made,” he said at his farewell press conference. “I’m not going to give you guys something on Jason Kidd or Devin Harris. . . . The deal was made, and at the end of the day, we’re here today.” The assembled writers were no doubt grateful to Johnson for confirming their presence, though most still had no idea what he thought of the trade.

Where Johnson is a master of meandering, Washington is the prince of pithy. “Good runners get bases when they can,” he told the Dallas Morning News recently. “Great ones get them when they have to.” The newspaper printed this as if it were a pearl from the mouth of Casey Stengel instead of a statement that is so universally applicable as to be worthless. (Good plumbers fix leaks when they can. Great plumbers . . .) During the first two months of the season, I made a habit of seeking out Washington’s quotes to see whether he could top himself in blandness, and I found this sampling of his managerial poetry: “He bent, but he didn’t break,” “He’s a gamer,” “Right now, it’s still a day at a time,” “It was just one of those nights,” “We try to be smart,” “We went out there to play,” “We haven’t come to any conclusions yet,” and my favorite, “We will show back up tomorrow.”

I had a hunch that Phillips was also a master of coachspeak, but one so rarely manages to hear him over the din of Jerry Jones. Last year I tracked down Phillips at the NFL owners’ meetings in Phoenix. He is a big-bellied, almost bashful man—if he wasn’t a coach, he would have made a great small-town sheriff. This gentility is a clever ruse, I soon discovered, because it obscures the fact that when he is talking, he’s not really saying anything. I trailed Phillips around for a few minutes and attempted to record his thoughts. When I looked down at my notebook later, I found only a few illegible words, one of which was “yes.”

Why does coachspeak persist? Why don’t more coaches channel the borscht belt-style comedy of the late, great UT basketball coach Abe Lemons (“Doctors bury their mistakes, but mine are still on scholarship”) or the wit of legendary UT football coach Darrell Royal (“Fat people don’t offend me. What offends me is losing with fat people”)? Compared to his son Wade, Bum Phillips, late of the Houston Oilers, was like a cast member on Hee Haw. Even that old cuss former Dallas Cowboys coach Bill Parcells was merciful enough to treat the sportswriters to the occasional bon mot. (Parcells once said that safety Roy Williams was “a biscuit short of a linebacker,” a statement that has proved sadly accurate as of late.)

Grant Teaff, the former football coach at Baylor who is now the executive director of the American Football Coaches Association, thinks that coachspeak emerged after the fraying of the relationship between coach and sportswriter. During the seventies and eighties, Teaff maintained friendships with the sportswriting class, even the punks who would hammer him for losing to Rice. In return, Teaff says, he expected a great deal of the coach-writer dialogue to remain off-the-record. The emergence of a more aggressive media has caused coaches to bite their tongues. “There’s also a guardedness now because of the vastness of the so-called media,” Teaff says—meaning, the various Internet outposts that cover sports.

Case in point: Last September, Oklahoma State’s Mike Gundy lambasted a writer he felt had been unduly harsh toward his quarterback. “Come after me!” he shouted. “I’m a man! I’m forty!” A few years ago, this might have made the rotation on SportsCenter. These days, Gundy is another freak act on YouTube. How many colorful answers do you think Gundy will offer this year?

Yet there’s another reason coaches tend to lapse into cliché: Much of their lives is cliché. A coach’s interactions with his players, as John Madden once wrote, are not unlike the ways in which one talks to a child. “Just relax.” “Go out there and have fun.” It is inevitable that some cheerful banality will spill over into the press conference.

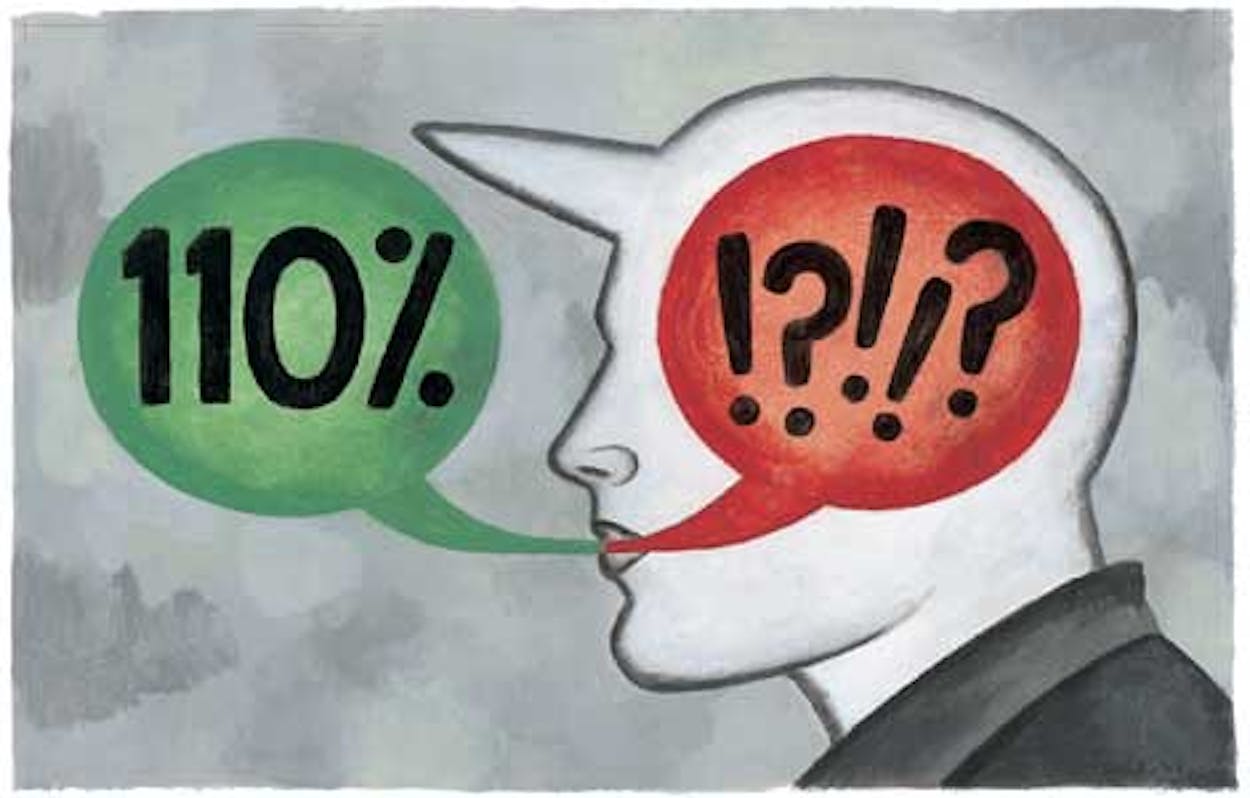

But I believe that there is a more devious explanation for coachspeak. Like a White House press conference, it creates a fog of confusion, an information-free zone. I am not spoiling any trade secrets by admitting that sportswriters (and here I include myself) often have very little idea of what goes on during a game. If Cowboys running back Marion Barber has a poor outing, the writer could speculate on the reasons—bad running, bad blocking, bad play-calling, stolen offensive signals. But actually knowing why Barber had a poor game requires a level of sophistication that few writers possess.

A coach walks into a press conference knowing he has the advantage. He stares out over a room of benighted writers and watches as they timidly try to pry information out of him. “What happened out there tonight, Coach?” He stonewalls (Parcells), stares daggers (Gregg Popovich), meanders (Mack Brown), and cajoles (Jimmy Johnson)—anything but disgorge a thought that would illuminate the contest just completed. Coachspeak is a byproduct of our own sportswriterly ignorance. Put another way, you might say that we’ve put the coach in a position to win.