Jackie Young turns her car into the parking lot of the Food Town grocery store in the Houston suburb of Highlands and pulls up near the entrance. “Let’s people-watch,” she says. Within a few minutes, a woman carrying a shopping bag falls in the parking lot, her legs buckling beneath her. Two men help her to her feet. Then Young’s mother, Pamela Bonta, arrives and begins passing out health flyers to shoppers. Over the next half hour, a parade of other infirmities materializes: six people with limps, a man whose legs are covered in rashes, and a man with an arm brace. When a sallow-faced man with a leaking open sore on his leg heads toward the market, Bonta hands him a flyer. He’s suspicious. “EPA stuff?” he growls, making his way with his cane toward a trash can. “No, I’m not with the EPA,” she assures him. He pauses, reads the flyer, and stuffs it in his pocket.

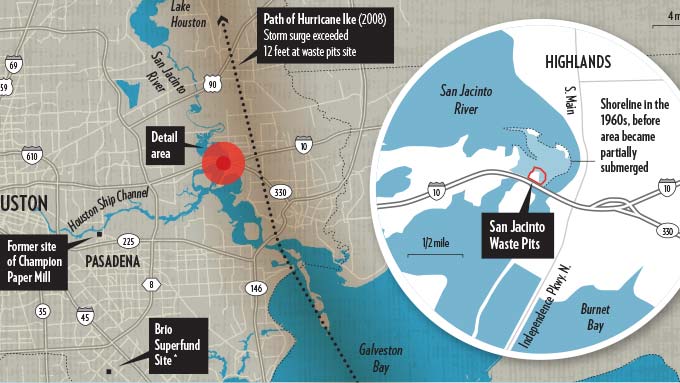

Distrust of the Environmental Protection Agency runs deep in Highlands. The community, on the eastern outskirts of the city, sits on the banks of the San Jacinto River, an area crowded with smokestacks that send black clouds into the air day and night. Chemical burn-offs are a regular occurrence, and five Superfund sites—areas of high toxicity that are on the EPA’s National Priorities List—lie within a ten-mile radius. One of them, the San Jacinto Waste Pits, sits two miles south of Highlands. Locals believe that the EPA has done little to protect them, despite the presence of so many toxins and the poor health of so many residents.

Young should know. In 2003, when she was a teenager, she, her mother, and her stepfather, John, moved into their dream home on North Main Street. The five-bedroom house had a tennis court, acres of pasture for the family’s horses, and its own water well. The family lived there for a year or so before Young started experiencing health problems—joint pain, digestive issues, and ovarian cysts. A year after that she left home, eventually settling in Austin, where she enrolled in college, though she continued to visit her parents often. Soon after she arrived in Austin, however, she began experiencing incapacitating fatigue, and in 2008 her parents persuaded her to move back home.

Yet Young’s health continued to decline. In May 2010 she experienced the first of many seizures. Her mother took her to multiple doctors, none of whom could pinpoint the cause; a few suggested that Young—who worked part-time as a model—had an eating disorder. As the months went on, she began to lose her hair and the use of her hands. Her weight dropped from 125 pounds to 90 pounds. She suffered repeated kidney infections and underwent thirteen rounds of antibiotics in one year. By 2011 she was having as many as seven seizures a week.

And then John, who had been experiencing some fatigue of his own, started to have much graver problems. He broke a rib in November 2011. Four months later he broke his back while lifting a piece of damaged fencing in the backyard. In March 2012 doctors gave him a bleak diagnosis: he had multiple myeloma, a rare form of blood cancer, in 80 percent of his body. “I was literally hand-feeding him and helping him go to the bathroom,” Bonta says. “And Jackie too. I had to wash her hair, turn the pages in her book, and drive her to school.”

At the time Young was pursuing a degree in environmental geology at the University of Houston–Clear Lake. As part of her class work, she compared a sample vial of Houston tap water with water from her family’s well. After her professor pointed out that flecks of iron were floating in one of the well samples, she decided to have her blood, hair, urine, and nails tested for the presence of heavy metals. The results were stunning. “I had high levels of nineteen of the twenty-one heavy metals I was tested for,” Young says. “Uranium, lead, arsenic, mercury. You name it, it was in me. So I started researching my environment day and night.”

She soon discovered the history of the San Jacinto Waste Pits. In 1965 Champion Paper Mill, which was located in Pasadena, contracted with McGinnis Industrial Maintenance Corporation to dispose of Champion’s industrial waste. MIMC dug pits along the San Jacinto and dumped toxic waste there until 1967, when the unlined pits reached capacity. The following year, MIMC’s board of directors voted to abandon the site. Over the next four decades, the riverbank that separated the pits from the river gradually eroded, until large sections of them were submerged beneath the water. The site was basically unknown to anybody else until 2005, when the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department realized what was there. In 2008, the EPA granted it Superfund status but initially did nothing to stop the flow of poisons—such as dioxin, one of the most toxic chemicals known to man—from the pits.

Young came to suspect that her family’s troubles could be traced back to the site; in 2008 Hurricane Ike struck just east of the pits and flooded the Highlands area. Her health problems escalated after that. “I try not to think about it,” she says, “but my dad may not be able to walk me down the aisle. I may not be able to have kids.”

Young and her mother wanted to know if they were the only family in the neighborhood experiencing these sorts of symptoms, so they started knocking on doors. Nearly every opened door produced a story of illness. “Every day I run into somebody who has leukemia, multiple myeloma, lymphoma, lupus,” Bonta says. The Bontas knew they needed to move off the property, but they couldn’t in good conscience sell it to someone else. Their only option was to allow the bank to foreclose and to walk away from everything, which is what they did. The Bontas moved to Cypress and Young left for Houston. Young’s health slowly improved, though she is still being treated for endometriosis. John remains in bad shape.

Convinced that others were suffering, Young and her mother continued to visit Highlands, knocking on more doors. Not everyone was receptive to their overtures. “People tell me, ‘You’re not going to get nothing done in this town,’ ” Bonta says. But they discovered that there were others who shared their concerns. In 2010 the nonprofit group Texans Together had begun a campaign to inform Highlands residents about the dangers of the pits. Young started volunteering for the nonprofit’s San Jacinto River Coalition, eventually signing on full-time as the coalition’s director.

Texans Together wasn’t the only organization grappling with the issue of the waste pits. In 2011 the Harris County Attorney’s Office filed a lawsuit against International Paper (which had merged with Champion Paper years earlier), MIMC, and MIMC’s parent company, Waste Management, for violating the Texas Water Code, Health and Safety Code, Solid Waste Disposal Act, and Hazardous Substances Spill Prevention and Control Act and conspiring with one another to violate these codes and acts.

The case finally went to trial last October. Young knew that it would be tough going; the evidence was complicated and the defendants had well-funded legal counsel. But she was encouraged by the example of a new friend she had made several months earlier, a woman named Marie Flickinger.

In 1984 Marie Flickinger was living in the southeast Houston suburb of South Belt when the EPA notified residents that a nearby waste site known as Brio would be declared a Superfund site. EPA officials assured residents of the Southbend neighborhood—the part of South Belt that adjoined the site—that Brio posed no health risks. Flickinger, the publisher of the community newspaper, the South Belt–Ellington Leader, believed them. “I thought, ‘It’s the EPA. They’re the Environmental Protection Agency. That’s their job,’ ” she says. She printed front-page articles in the Leader repeating the EPA’s claims.

One assertion that had been made by the EPA was that virtually no tars—clumps of thick, black, highly toxic waste—would surface in the area. Flickinger accepted that this was true until 1987, when a friend told her he had seen the tars himself. He took her to a property near Brio and the neighboring Dixie Oil Processing Superfund site, shoved a wooden stake into the ground, and then pulled it back out. Black, sticky goo dripped from the stake.

Though the tars were a surprise to Flickinger, she was already aware that on the Brio site, near where they stood, was a grouping of dirt mounds spread across a fenced-in landscape. These mounds were made up of soil contaminated by industrial waste. Neighborhood kids had discovered them and, despite the fencing, often rode their bikes on them, calling the accidental moguls the Honda Hills.

Flickinger phoned the EPA to tell them what she had seen. “We can’t function as guardians of the neighborhood children,” one EPA official told her when she mentioned that kids played in the area. “People—parents to start with and other people who are concerned about this contamination—have to make some effort to keep those children away from that stuff.” Flickinger was shocked. Hadn’t the EPA told everyone that the site posed no health risk? And hadn’t she been informing her readers that those reassurances were true?

Flickinger quickly became fixated on Brio. Because she had no scientific training—she had only a high school education—she started attending conferences around the country to learn more about toxins. She pulled eighteen-hour days poring over documents, reached out to politicians, and paid for independent research out of her own pocket. “I got obsessed with it,” Flickinger says. “I gained, like, sixty pounds during that time. Between eating like I did then and not sleeping, I ended up with diabetes. But I couldn’t not do it.” Today her office still bursts at the seams with evidence from that time. Boxes and binders labeled “BRIO” in thin black marker fill storage closets. Two large metal filing cabinets overflow with old newspaper clippings and documents.

She learned that between 1956 and 1982, numerous companies, including Monsanto and Texaco, had disposed of toxic material at Brio. Aerial photos indicated that over the decades the waste had migrated into the community. Tar seeped through cracks in the driveways of homes close to the site and surfaced near the baseball fields where Flickinger’s sons played Little League.

In 1988 Cheryl Finley, a South Belt resident whose daughter was born without ovaries, organized a group of parents to survey Southbend and gauge how many families had sick children. Decades later, Flickinger pulls a copy of the survey out of one of her filing cabinets. Handwritten notes detail the health of 30 families; 21 suffered from problems such as heart defects, seizures, and chronic urinary tract infections. Twelve of the thirteen women they surveyed who were pregnant gave birth to children with birth defects. Tellingly, the survey was never finished; after reviewing their initial findings, most of the parents who were conducting the study moved away.

The Leader’s coverage was relentless. But rather than unite in outrage, the community grew polarized. Residents of Southbend believed Flickinger, but the remainder of the South Belt community thought she had come unhinged. When she began to publicly advocate for the closure of Arlyne S. Weber Elementary School, a group of mothers picketed a school board meeting, chanting, “Close the Leader, not Weber.” Real estate agencies and other businesses stopped advertising in the paper; revenue dropped 50 percent in one year. Flickinger understood why no one believed her; she had no formal background in science, and the EPA had science that seemed to back up its claims.

But the quality of that science was suspect, due to a possible conflict of interest. Because the Superfund law dictates that the responsible parties pay for the studies that indicate what the final remediation should be, they often have influence over the results of those studies. In Brio’s case, it was discovered that the scientific documents had been tampered with. Environmental contractors who were hired by the companies to analyze Brio found that the waste was covered by only 6 inches of earth in some areas. But court documents indicate that before the report was handed over to the EPA, the number was modified to indicate that no waste could be found within 78 inches of the surface. Methodology was also a problem. According to Flickinger, the companies set thresholds so high when testing for toxicity in the air that there was essentially no chance that they would regard anything they found as dangerous. Yet the EPA took the study at face value.

In 1991 the EPA approved a plan to incinerate the site’s waste, a decision that Flickinger believed was a bad idea. She knew that the site hadn’t been tested for dioxin, a chemical that wouldn’t be destroyed by the incinerator. (At the time, the EPA did not require testing for dioxin.) Flickinger tried to convince the EPA that incinerating the waste would send chemicals into the skies above the subdivision, but the agency went ahead with its plans anyway. By 1994 a $50 million incinerator loomed over the site. “I drove by it and it just hurt my soul,” she says.

Her last-ditch attempt to stop the incineration was to appeal to Bob Martin, who had recently been hired as the EPA’s ombudsman. Martin, who was quickly developing a reputation as a man who wasn’t afraid to ride herd on his bosses, studied Flickinger’s evidence, and, as a result, the EPA told the companies to test the site for dioxin. They declined to do so, and ultimately the incineration plan was cancelled. It was the first time that the EPA had ever overturned a final remediation solution. South Belt resident Catherine O’Brien, who worked closely with Flickinger on Brio, still laughs when she remembers the day. “We were jumping up and down, doing dances, high fives,” she says. “If we’d been football players, we might have swatted each other on the butt.”

Flickinger and other residents were asked by the EPA to help determine the new remediation plan and eventually agreed upon a comprehensive method of containment; digging all the chemicals up would have exposed them to the air, which would have posed its own dangers.

By 1998 the entire 677-home subdivision of Southbend had been bulldozed, as had Arlyne S. Weber Elementary School. Eventually, residents won a $207 million settlement from six chemical companies and a developer. In 2002 the school was rebuilt in a different location. Flickinger attended the ground breaking of the new Weber Elementary, where she met the daughters of the woman for whom the school is named. When Flickinger approached them to express her regret about what had happened to the original building, they told her not to worry. “Mother would have supported what you did,” one of them said.

Click here to download a PDF of this infographic.

Jackie Young and Marie Flickinger met for the first time last May, at the recommendation of one of Young’s volunteers. “We could have sat there all day talking,” Young recalls. “The things she was up against all those years ago are the same obstacles people are facing today.” Listening to the two women, it’s tough to shake the sense of history repeating itself. Once again, toxins are threatening a community; once again, the companies responsible for the pollution had been accused of submitting questionable science to the EPA and are vying for the cheapest remediation solution; and once again, government agencies are regulating with more of a velvet glove than an iron fist.

In 2010, two years after the EPA added the San Jacinto pits to its National Priorities List, the agency ordered the responsible parties to install a temporary armored cap over the site, which was intended to prevent the waste from escaping while the site was still being evaluated. In 2012 part of the cap eroded during a rainstorm.

In the absence of aggressive action by the EPA, others have jumped in to keep the issue in the public eye. Last July Samuel Brody, a marine science professor at Texas A&M University at Galveston, announced the results of a study that Young’s employer, Texans Together, had hired him to conduct. The goal of the study was to evaluate what would happen to the San Jacinto pits in the event of a flood. Brody found that toxins could easily spread throughout the community. At a press conference, he referred to the site as “a loaded gun.”

The Harris County Attorney’s Office, which filed its civil suit against Waste Management, International Paper, and McGinnis Industrial Maintenance Corporation four years ago, has also continued to dog the EPA. Last May county attorney Vince Ryan submitted a letter on San Jacinto to the EPA’s National Remedy Review Board. Ryan pointed out gaping holes in the research the EPA had ordered the three companies to conduct. Flickinger had warned Young that the testers might set the detection thresholds too high, and that’s exactly what Ryan claims happened: the levels for testing for dioxin in the groundwater were set many times higher than what the state requires. (Spokesmen for the companies stated that they have done everything in accordance with EPA policies.) In July the EPA agreed that the companies’ science was insufficient and brought in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to conduct its own research; the Corps is expected to complete its study this month.

On October 16 dozens of onlookers squeezed into the courtroom of district court judge Caroline Baker to hear opening arguments in Harris County’s long-awaited civil case against the three companies. An overflow of perhaps two dozen more spilled into the lobby. Young, who attended much of the trial, couldn’t help but notice that a fair amount of significant evidence was excluded by Judge Baker. “It was the things a jury would have looked at in determining liability,” says Rock Owens, an assistant Harris County attorney.

On November 13, as the month-long trial was coming to a close, Baker announced that Waste Management and MIMC had decided to settle the case for $29.2 million. After the announcement was made, the attorneys for the plaintiffs and for International Paper made their closing statements, then Judge Baker gave instructions to the jury. No one expected a verdict that day. Yet late in the afternoon, the jurors filed in and delivered their judgment: International Paper was found not liable.

“I was really disappointed that residents of Harris County had the opportunity to hold polluters accountable and didn’t,” Young says. “At the same time, things were said in that trial that were not true.” But the $29.2 million settlement appears to be the largest amount collected for water pollution in the history of Texas. And the legal battles are hardly over. Harris County has filed a motion for a new trial against International Paper, claiming that Judge Baker made a series of errors in her rulings. Nearly two hundred Vietnamese fishermen are suing over the contamination of marine life in the San Jacinto River and Galveston Bay, which has cost them their livelihood. More than one hundred residents living near the pits have also brought a mass-action personal-injury lawsuit. And later this year the EPA will make a decision about how to best clean the site.

For her part, Marie Flickinger hopes that some of these people will get the sort of justice that she earned for her community years ago. “Basically what you have is a David and Goliath situation, only Goliath usually wins,” she says. “The chemical companies outgun everyone.” Sitting in her office at the Leader, she sifts through decades-old documents demonstrating corporate and state malfeasance that she can’t quite bring herself to get rid of. “It wouldn’t be a big deal thirty years later,” she says, “if it wasn’t for the fact that nothing has changed all that much.”