It was the middle of June and the creative staff of the Richards Group, one of the more distinguished advertising agencies in the country, had gathered in its Dallas conference room to hear that the great chase was on. “I want you to start thinking about Southwest Airlines,” said the silver-haired Stan Richards, an unflappable, slightly remote man often referred to in the trade journals as the guru of Dallas advertising. From the head of a long, perfectly polished table, Richards peered down at his young Turks, all of them in their twenties and thirties, as sleekly dressed, in colorful striped shirts and silk ties, as models on the pages of Gentlemen’s Quarterly. Under his imperious tutelage, these 16 writers and 21 art directors had become part artists and part showmen, masters at the craft of teaching people to want things. Some of them could look on the walls of the conference room and see their own names printed on the various awards they had won-their boss’s not-too-subtle way of showing what it takes to receive his blessing.

“I am going to want your best ideas for this project,” was all Richards said before moving on to another subject. As usual, his carefully modulated voice and perfectly composed face gave away none of his emotions. But to his staff, his words were like a jolt of electricity. The members of the creative team glanced sideways at one another. The rumors were true. They were going to go after the most prized advertising account in the state. For weeks, ever since Southwest Airlines had announced that it was putting its $15 million creative advertising account up for review and would be drawing up a list of five agencies to vie for the business, some of the hottest shops in the country had let it be known that they wanted in. Most of the large Texas agencies, of course, were also contacting the airline. Stan Richards was no exception. Though his agency’s campaigns have been honored in every major advertising competition—since its inception in 1976, the Richards Group has won seven Clios, the advertising industry’s version of the Oscar—winning the Southwest account would secure his place in advertising’s big leagues. Every advertising mogul wants an airline: It’s his chance to show off his work to the rest of the country.

“From the day Southwest was born,” says Rod Underhill, one of the principals with the Richards Group, “Stan has been watching it and wanting it and feeling he was the right choice for it—to make a difference in its future.”

Southwest Airlines officials knew they would need powerful advertising to carry them through the nineties. Last year the successful Dallas-based airline went past the $1 billion mark in revenues for the first time, but it is planning to double its business over the next five years, moving into hostile markets where the competition is unforgiving. In American business today, with so many good companies offering bewilderingly similar products, advertising has become perhaps the critical factor in the consumer’s decision of which one of those products to buy. The environment is not so much one of innovation as it is one of marketing—which means the adman, more than ever, has become its superstar.

And if one is looking for such a star, one doesn’t have to go much farther than the twelfth and thirteenth floors of a gray granite-and-glass high rise on the North Central Expressway in Dallas, where a trim 57-year-old man—who sometimes shows up at his office at four in the morning to begin his day and often skips lunch in favor of a 5-mile run—presides over his agency with baronial splendor. Behind his aviator glasses, in dress shirts, suits, and Italian shoes, and always holding an elegant pen that looks like it came from Neiman Marcus, Stan Richards is as close to an aristocrat as the always-changing world of advertising has to offer. His office is immaculate and intimidating. His post-modern desk is black, his office walls are as white as canvases, his chairs are made of black leather and chrome. Richards’ employees talk about “getting a grom” when they sit before him in his office and present him with an idea for an ad. If he doesn’t like it, he stares unblinkingly back at them, a wintry smile on his face. At moments like these, for his underlings, the “grom” (what they call the little button on a chair’s seat cushion) feels like it is grinding into their rear end.

Though the creative departments of many well-known ad agencies are notorious for their freewheeling characters, Richards runs his agency like a blue-blooded law firm. He does not tolerate staffers’ raising their voice. No one is allowed to criticize another employee. The men wear ties, and the other women wear dresses and heels. Everyone must report to the office by eight-thirty, and long lunches, which many ad executives have turned into an art form, are discouraged. No interoffice dating is allowed. There are no company picnics or parties. To a visitor, the pristine offices of the Richards Group have the tenor of an Ivy League library, a quiet refuge where ads are studied as if they were Renaissance manuscripts. “Stan is not one of the boys who comes into your office, throws his feet on the desk, and tells a bunch of stories,” says Rich Flora, a senior writer at the agency. “The office is not fun and games to him. He has these exacting standards about what makes a good ad, and he will not allow an ad we do out of this agency, no matter how small it is, if it doesn’t meet those standards. He puts his head down and works and expects us to do the same.”

Yet out of this traditional corporate culture has come an array of humorous and whimsical advertising campaigns that have set a creative standard in the Southwest for the past decade. The Richards Group’s techniques are now mentioned in the same breath as some of the top ad shops in the country, and their success has engendered a huge amount of speculation in the industry about just how Stan Richards operates. “No shop in Texas consistently produces well-executed print work like they do,” says Richards rival Dick Smith, the executive creative director and a partner in the Houston agency Taylor, Brown, Smith, and Perrault. Besides its reputation for beautifully designed, elegant print ads, the Richards Group also has made a name for itself with its innovative use of celebrity spokespersons. The agency had country music singer Mel Tillis stutter through a Whataburger commercial and placed actor Martin Mull in an absurd-looking red telephone suit (Hello, Mr. Telephone here!”) in order to promote a long-distance service. In its most famous campaign to date, it turned to a folksy Alaskan radio commentator named Tom Bodett to wax philosophical about the simple pleasures of Motel 6 (“You can’t get a hot facial mudpack at Motel 6 like those fancy joints…but you will find a clean, comfortable, nonfancy room.”). Richards explains : “If there’s one word that I want to describe our advertising , it’s ‘endearing.’ My rule is that everything that comes out of this agency must make people feel warm and affectionate toward our client.”

There was obviously little surprise that the Richards Group was named one of the five finalists for the Southwest Airlines pitch. Some members of the local ad community, who knew that Richards was friends with Southwest’s marketing director, Don Valentine, a key figure in determining the airline’s future advertising, speculated that Richards was the clear favorite.

But winning Southwest would not be so easy. Although three dark-horse candidates were included in the final selections—Ayer/Southwest in Dallas, Ketchum Advertising of San Francisco, and Cramer-Krasselt of Chicago, none of whom were given much of a chance by insiders to win—the other agency that made the list happened to be Richards’ fiercest and most combative adversary. GSD&M, the high-spirited Austin shop with a cheeky music-driven style, was the first group to present a serious challenge to Richards’ creative rule in Texas. Moreover, GSD&M had held the Southwest account for the past nine years, and was ready to wage war to keep its airline. For most industry observers, the battle for Southwest had turned into a long-awaited showdown between Richards and GSD&M.

Formed in 1971 by six wild-assed University of Texas students, GSD&M operates in a style utterly different from that of the Richards Group. The creative staff come to work in shorts and sandals—one writer regularly brings his dog along—and many of the offices look like something out of a David Lynch movie. In one art director’s office are an inflatable dinosaur, a stuffed crow hanging from the ceiling, a Shriner’s hat propped on top of a lamp, a Pee-wee Herman photograph on the wall, and a clock in the shape of Felix the Cat. The agency sponsors such events as Family Days, certain Fridays that spouses and children are invited to spend at the office; Net Positive meetings, at which the company’s leaders get together at the end of the week and talk about only the good things that happened to them; and an all-day company picnic called Adstock, a takeoff on Woodstock that features different groups in the agency performing in bad rock and roll bands for the others.

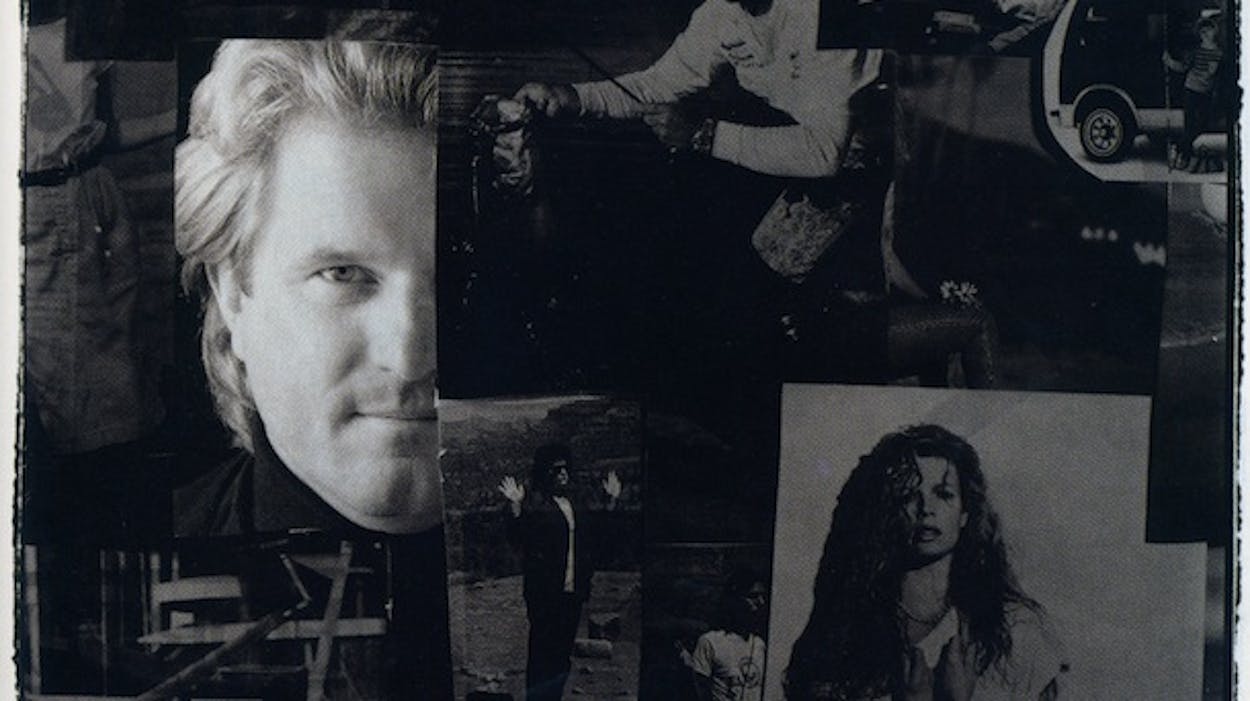

The agency’s blond-haired 41-year-old president, Roy Spence, is everything that Stan Richards is not. Best known for creating the commercials for Walter Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign, Spence comes to work in everything from Armani suits and boots to jeans and tennis shoes. On his left wrist he wears a purple macramé friendship bracelet. His green-walled office is jammed with uneven stacks of papers and pictures of his kids and his clients. While Richards is unflaggingly polite yet reserved around his employees, Spence bounds around like a puppy that has just been let out into the back yard, banging people on the back, asking about their families, and not giving a damn what time employees get to work as long as they get their work done. “Hey, Wild Man!” he calls out to whomever he sees as he struts down the hallway. If Richards stands for corporate button-down Dallas, then there is no doubt that Spence represents renegade Austin. Says Houston adman Dick Smith, “I can’t imagine Stan jumping on a table at a party like Roy once did, with a bottle of tequila in his hand shouting, ‘We ride at dawn like the breaking wind! Who’s with me?’”

Spence, a former high school quarterback, also relishes a fight, which he knew he was in for when the news came that Richards was going against him for the Southwest account. Although in the past few years GSD&M has been winning the high-profile national advertising accounts—like Coors and Wal-Mart—that Richards has never been able to get, Southwest was the agency’s flagship account. Its off-the-wall campaigns for the airline had given it a respected creative reputation in the advertising world and had helped Spence build GSD&M into the third-largest agency in the state, behind Dallas’ Tracy-Locke and Bozell companies, with $150 million in billings and two hundred employees. (Richards, with approximately the same number of employees, is behind him with $135 million in billings).

If heads of advertising agencies act a little paranoid, it’s because of the constant fear that one of their accounts will come up for review. The moment a corporation’s profits start to dip or there is a management shake-up, often the first thing the corporation feels it should do is change advertising agencies. It invites different agencies to make a pitch for its business, and sometimes, as in the case of Southwest, it requires “speculative creative” (the creation of a new ad campaign) as part of that pitch. Rarely do agencies get paid to participate in such a pitch.

Spence might have been stunned that Southwest officials had decided that his agency’s recent work was faltering enough to put the account up for review, but he was determined not to let anyone else get it—especially Richards. Not only did some GSD&M creative people consider the Richards Group stuffy and boring but they thought that its work was overrated. They also saw Stan Richards’ bid for Southwest as a dangerous threat, an attempt to take their jobs away. “Richards might have been the reigning heavyweight,” says Guy Bommarito, GSD&M’s executive creative director, “but we knew we had some knockout punches of our own. As we got into this, we realized that we all had one common mission—to get Stan.”

And so, the high-stakes drama was set. Each agency had a month to prepare a major new creative campaign for Southwest—including a television campaign, a variety of print ads, a separate campaign to introduce Southwest into a new city, and even a campaign to celebrate Southwest’s twentieth anniversary. They would then present their ideas to a team of airline officials, including company chairman Herb Kelleher. To the winner would go not only some $15 million worth of business but also bragging rights in an industry that prides itself on style as much as substance.

When Stan Richards and Roy Spence began their advertising careers in Texas, it would have been difficult to imagine them ever building the two most respected advertising firms in the state. Richards, the son of an Atlantic City bartender, came to Dallas in 1953 on his way to Los Angeles, where he figured he would eventually work. A graduate of New York’s Pratt Institute, one of the most prestigious graphic arts schools in the country, he brought with him a portfolio of cutting edge designs that one president of a Dallas agency told him was trash. “Dallas was such a backwater then that to look at Stan’s portfolio was equivalent to the way shocked audiences in France must have first reacted to the Impressionists,” says Bill Hill, the chairman of the Dallas agency Levenson and Hill.

At the time, major advertising in Texas was not recognized for its innovative creative work. Except for one award-winning Tracy-Locke campaign in the early seventies in which actor Avery Schreiber ate Doritos as loudly as he could, advertising from Texas agencies rarely attracted national attention. “At our big ad shops there was more emphasis on doing what the client wanted rather than doing a good ad,” says Russ Pate, a longtime Dallas columnist for Adweek, the industry’s bible. “There was so much money involved in servicing a big client that no one wanted to risk losing the business with an innovative campaign.”

But Richards stayed “because I knew I could do something new here.” He started his own design shop and began creating corporate logos, brochures, and annual reports for Dallas companies. His reputation spread as someone who had a contemporary, sophisticated look, with bold images and unpredictable typefaces. Even though he was a bit too formal and artistic for traditional Dallas advertising men—most leaders of advertising agencies come out of the account side of the business and have little creative experience—Richards knew how to bring in the business. By the late sixties he had fourteen designers working for him and was being hired by Dallas agencies to produce their ads for them. “Stan is called the father of Texas design because he cultivated so many young designers who have now become famous themselves,” says Jerry Herring, one of those early employees who now has his own well-regarded design studio in Houston. “He knew how to get the best work out of us. He would give us the same project and watch us compete madly with one another to see whose work he would accept.”

In 1976 the chairman of the practically moribund Mercantile National Bank in downtown Dallas asked Richards, who had yet to even form a full-service advertising agency, if he could come up with a campaign to get the organization growing. Back then, bank advertising in Dallas was appallingly boring: men shaking hands while an announcer said things like, “Give us an opportunity to say ‘yes.’” Richards realized his opportunity had come. His staff came up with a sleek new trademark, a flying M cutting through a graph. His theme line for the bank “Never underestimate the power of momentum,” didn’t even include Mercantile’s name, and the first television commercial he shot was this strange scene of dominos falling over the bank’s logo while the announcer talked about Mercantile gaining momentum. “We asked for something different, and I must say we got it,” says David Gravelle, who was then Mercantile’s director of marketing. Within a year the bank’s profits went up 22 percent. The Richards Group grew so quickly that in 1982 it was named by Adweek as one of the eight most creative advertising agencies in the country.

In the mid-seventies, GSD&M was also developing a name for itself, but with an earthier, blunter approach to advertising. For its first account, Country Club Malt Liquor, the creative head of the agency, Tim McClure, came up with the line, “It’s legal, but just barely.” Spence, when calling on potential clients to extol the virtues of his advertising agency, would show up in a tie-dyed t-shirt.

“We didn’t know what the hell we were doing,” says Spence. “We were so poor that I slept in the office and sneaked into the swimming pool at the health club next door to take my baths. I don’t think people perceived us as hippies, but they sure thought we were a different breed.”

Though he had little experience, Spence got himself employed to do political advertising for state Democratic politicians. When asked to do the advertising for Ralph Yarborough’s 1972 Senate campaign, Spence, who knew nothing about television, hired the man who would direct The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to create the Yarborough TV spots. While doing the advertising for Robert Krueger’s successful 1974 congressional campaign, Spence devised a scathing newspaper ad criticizing Herb Kelleher and some of Kelleher’s rich San Antonio cronies for supporting the other side. Kelleher was so impressed by Spence’s style that they became friends. In 1981, Kelleher hired GSD&M to create Southwest Airline’s advertising.

In those days, Southwest was only a $3 million account. GSD&M’s first major campaign for the airline contained the now-famous ad of a bumbling Kelleher getting locked out of his own airplane while describing the advantages of the ten-minute turnaround. Soon, GSD&M of Austin, Texas—hardly the advertising mecca of the world—was growing rapidly. In less than ten years GSD&M landed such accounts as the Wall Street Journal and Coors, which Ad Age said “stunned the industry.” Just as shocking, Spence was picked as Walter Mondale’s media consultant. And the agency began to produce award-winning campaigns like “Don’t Mess With Texas,” in which Texas celebrities like Stevie Ray Vaughan warned Texans not to litter. Early this year the GSD&M founders—the Big Chill generation gone advertising—became multimillionaires when they sold their company to a major London advertising firm in a five-year buyout plan totaling $48.5 million. Included in the deal was the provision that Spence and his partners still run the agency.

“GSD&M pulls a lot more of their creative from grass-roots America,” says Dick Smith. “You see more blue jeans in their ads, which is reflective of their own culture. From my perspective, Richards has an agency that is a little more designy and sterile.”

But the Richards Group—the largest privately held ad agency in the country with a sole shareholder (Stan Richards)—claims that by selling out to a larger firm, GSD&M will soon be told by outsiders how to operate the business. Richards staffers also dismiss GSD&M creativity, claiming that the Austin agency has had some seriously dull campaigns and has come to rely on formulaic musical jingles in almost all of its commercials. “If you don’t have anything to say, then sing it,” snipes Stan Richards. “And the reason I don’t use music is because I don’t believe any of my clients have nothing to say.”

“To me,” says Richards writer Rich Flora, “GSD&M is like the evil twin on a nighttime soap opera. We’re up here in Dallas standing for good and righteousness and great taste and not using scantily clad women in our advertising and no jingles. And then there’s that singing crazy bunch in Austin.”

Still, both styles have made their mark in Texas, whether it be GSD&M’s down-home campaign for Texas tourism (“It’s like a whole other country”) or Richards’ moving commercial depicting a new Vietnamese immigrant starting work at 7-Eleven (the spot won a Silver Lion award for advertising at the Cannes Film Festival). Through most of the eighties, Richards and GSD&M traded Adweek’s Southwest Agency of the Year award and won top prizes in local advertising shows. They were among the strong regional agencies around the country, like Hal Riney and Partners in San Francisco and Fallon McElligott of Minneapolis, who had begun to beat the traditional Madison Avenue agencies for big national accounts. But they kept their distance from one another: Richards says he has not met Spence and has only talked to him a couple of times on the phone. The two rivals were like lions on the prowl, always circling one another, waiting for that moment to attack.

When Stan Richards announced that he was looking for a great television campaign to pitch to Southwest Airlines, his admen felt a surge of adrenaline, as if they had just been asked to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. They could come up with anything they wanted. Here was their chance to prove to their demanding boss just how good they were.

An ad agency is usually split into five departments—the account executives, who deal with the agency’s clients; the media buyers, who select where the ads are to appear; the researchers, who conduct studies to decide what consumers want; the traffic-production teams, who keep the ads moving from initial production to actual production; and then the “creatives” who are the art directors and copywriters. Ultimately, the reputation of any agency depends on the ideas that come from the minds of the creatives—people who, in the eyes of the other departments, are temperamental types with the humility of professional tennis stars, who like to say “Hey, dude” to one another in the hallways, and who spend long periods in their offices staring out the window or throwing pencils into the ceiling. When someone asks what they are doing, the creatives will always say, “I’m concepting” which means they are allegedly thinking up ads.

Once a disreputable cultural stereotype, the infamous man in the gray flannel suit, the adman today has become a kind of celebrity. A person who creates just one good advertising campaign for a product like feminine hygiene spray receives numerous awards (no business holds more awards shows for itself than advertising), is the subject of glamorous profiles in the trade magazines, and gets treated at media parties as if he had written a best-selling novel. The word “adman” incidentally, is still applicable, for the creative side of the business is like a boy’s club: of GSD&M’s 31 art directors and writers, only 7 are women and of Richards’ 37 creative staffers, 6 are women.

Nowadays, with the public bombarded with so much advertising, a good creative who devises ads that stand out can command a phenomenal salary. A top-level creative director for a big Dallas ad agency, for example, makes as much as $250,000 a year. It has been said that the only way to make that much money writing so few words is to write ransom notes to millionaires.

“We just find ourselves terribly interesting and very important—the most self-absorbed people in the world,” says John Davis a GSD&M senior writer. Indeed, for today’s new baby-boomer breed of creatives, advertising is the popular art form of our time. Raised on television—it is not unimportant that one of their first heroes was advertising executive Darrin Stevens from the sixties sitcom Bewitched—they began thinking visually at an early age. They also actually liked staring at advertisements; it was how they learned about American culture. By the time they had grown up and were ready to write ads of their own, they didn’t see advertising as part of a process that helped sell a product. Advertising was the product.

Among the young talents at the Richards Group, there is always a sharp sense of in-house competition to see who is the best (at Richards, like at most agencies, a writer and an art director are paired together to devise ads). After the first Southwest meeting at the Richards Group, Brian Nadurak, an intense, pony-tailed 30-year-old art director, walked into the office of his partner, writer Thomas Hripko, and said, “We’ve got to form a plan of attack and win,” Hripko, the 31-year-old author of many of the prizewinning Motel 6 scripts, agreed. “I want to blow everyone’s shit away,” he solemnly told Nadurak.

If there is one person who seems out of place working for the strait-laced Stan Richards, it is Thomas Hripko. Cool and sardonic, a former lead singer of a rock band who goes home every day at lunch to make himself a peanut butter sandwich and watch The Dick Vandyke Show re-runs, Hripko seems to be, in the words of one senior art director at the agency, “living on another floor than the rest of us.” A few years ago, when someone at the office commented that his hair was getting a little shaggy, Hripko got a burr haircut. Every day, when he arrives at his office, he turns off the overhead lights and sits in the darkness, his face bathed in the amber glow of his computer screen. When he leaves, he turns the lights back on. Nadurak, a graduate of an art school in California, has his own peculiarities. When he is “concepting,” he slumps down in his chair, shuts his eyes as if taking a nap, and tries to reach an alpha state, where he says his brain becomes more creative. Hripko and Nadurak are so cautious that at the end of the day, they hide or take home the ads they’re working on.

Yet one of Stan Richards’ strengths is in spotting unusual talent and getting out of its way. In 1985 he hired Hripko, who had no advertising experience, base on some crude stick-figure drawings with clever slogans written underneath them that Hripko had sent him. Two years ago Hripko was named one of the “hottest copywriters in America” by Adweek. Shrewdly, Richards makes people like Hripko wear ties because he figures his corporate clients will be more willing to buy into some of the agency’s more bizarre ideas if wild-eyed creative guys like Hripko merely appear to look conservative and responsible. “Stan might have some weird ways about him, like this tie thing,” says Hripko, “but he has created a spirit around here where we all know we can do great work. At other agencies, your stuff has to pass through teams of associate creative directors and then senior creative directors and then account executives, all of whom want to change it. Here, we go straight to Stan with an idea, and if he likes it, we produce it.”

Hripko and Nadurak planned to blitzkrieg Richards with as many campaigns as they could conceive. Feverishly, in Hripko’s dark office, they threw out ideas with Uzi-like speed, finishing each other’s sentences, their eyeballs so wide with excitement that they looked as if they were about to crack up. Hripko came up with the idea of using Ben Stein, the actor who portrayed the hilariously dull monotonic-voiced teacher in the movie Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and now the same sort of teacher in the sitcom The Wonder Years. Stein dryly gives the class a word problem comparing two airlines. He pulls down a chart and compares airline A (Southwest) which flies from Dallas to Chicago for $100, with airline B (a competitor), which flies the same route for $200. “Plane B serves lunch,” whines Stein. “Plane A doesn’t. How much does the lunch cost on plane B?” Stein looks impassively at his class. “Anyone?” he asks. “Anyone?”

Nadurak created a campaign called “Herb’s Home Videos,” in which Herb Kelleher, who hasn’t minded playing hammy roles in previous Southwest advertising, shoots and narrates his own commercials with a video camera—and in the process manages to get in the way of his employees—as a way of showing Southwest as inexpensive but fun. In one commercial, while explaining that Southwest holds the record for the fewest lost bags, Kelleher films a baggage handler at work. The baggage handler tries to get Kelleher to put the camera down and give him a hand.

In all, Hripko and Nadurak came up with seven campaigns, including one showing a grumpy old man who hates flying Southwest Airlines because he likes his flights to arrive late so he can thus be late to meetings and look more important. “God, this stuff is going to kill them,” Hripko murmured at one point, staring hard into his computer screen.

But he knew the other teams would also be gunning for Stan’s favor, including Gary Gibson and Doug Rucker, two award-winning senior creative heads for the agency—“The two guys,” says Hripko, “who I most like to beat.” The bearded, soft-voiced Gibson, who at 36 is one of the oldest members of the creative staff, and 33-year-old Rucker, one of the agency’s snappiest dressers, down to his antique gold pocket watch, work in a rather comatose style: They sit for hours in an office, staring blankly like two caged owls, saying little until just the right idea hits them. But they are considered by one GSD&M official to be “the two biggest hitters at Richards.” For Southwest, they were feeling the pressure—nothing was coming. Finally, after days of false starts, they devised one commercial showing a series of jets from other airlines going down a runway while “Pomp and Circumstance” plays in the background. Then comes a Southwest jet, and the music suddenly changes into a boombox rap song while the announcer talks about Southwest being able to do the same things the other airlines do, only without being so stuffy. When Hripko heard it, he said a little gleefully, “It’s off the mark.”

Richards teams came up with about fifty different campaigns, ranging from the absurd (a proposal to put Kelleher in a ballerina outfit and have him twirl around on a runway while talking about Southwest’s quick arrival-to-departure turnarounds) to the charming (ads that showed what could have happened in Kelleher’s childhood that made him create the kind of airline that he did. In one spot, little Herb is in his high chair, his mouth firmly shut as his mother tries to feed him. She pretends that her spoonful of food is an airplane and asks him to “open the hangar.” Little Herb refuses and starts crying as an announcer explains that because of Kelleher’s “passionate disdain for airplane food,” Southwest doesn’t serve it).

Through meeting after meeting, Stan Richards sat quietly. Occasionally he would raise an eyebrow, show a slight smile, chuckle—beautiful pieces of miniature facial engineering. “I need to think about that,” he sometimes said about a campaign. Or, “Okay, thank you,” which meant that he hated it. Finally, eleven working days from the agency’s presentation to Southwest, he knew he must make a speech.

His eyes swept the room; his people felt as if they were being stared at by an atom bomb. “We’re not there with our ideas,” he said in his meticulous diction. “We’re not even close. I don’t see you working hard enough or spending the time it’s going to take to get this right. Now what should we do? Should we drop out of the presentation? For I assure you, I am not going to have us to go into that presentation and embarrass ourselves. We are either going to be great or we will not do this at all.” He rose and left the room.

“It sent a chill down everyone’s spine,” recalls Gary Gibson, who has worked for Richards since 1977. “It was the first time anyone had ever seen him get mad. I think a lot of us began to realize how desperately he wanted this account.”

Two hundred miles away, the atmosphere at GSD&M was like a high school pep rally. Roy Spence, fond of spouting out slogans to pump up his workers—“Keep your eye on the prize!” “If you don’t live on the edge, why live at all?” “Status Go, not Status Quo”—was prowling the halls, teaching his staff a new phrase, “The Power of One.” “I want us to feel some awesome positive energy,” says the theatrical Spence, his arms waving around as if trying to get out of an overcoat. “We needed to feel inseparable, knowing that together we could rise up to any challenge that came our way.”

“You have to remember that Roy’s attitude towards everything in life goes back to his high school days in Brownwood, Texas, where he was the quarterback,” says GSD&M writer John Davis. “All the kids were small, none of them good enough to get college scholarships, but as a team, they won the state championship. Roy is always the guy that sticks his head in the huddle and says, ‘Hey, we can win this thing.’”

A group of seven writers and art directors was picked to come up with the new Southwest campaign. Calling themselves the Warriors and wearing Rambo-like camouflage bandannas and occasionally donning bathrobes, they would arrive at a conference room (that they called the War Room) by seven-thirty in the morning and stay well past midnight. Other staff members would bring them food or take care of their homes and baby-sit their children. For 28 days they worked nonstop, writing down every idea they could think of and sticking them on a War Room wall. Whenever someone would come up with a particularly good idea, the Warriors would whoop and give each other high fives. Spence would regularly pop his head in and call them the Wild Men. Frankly, they were a bit odd. When things got tense, one of the Warriors would do a bad Elvis Presley impersonation and another would do a Jerry Lewis act in which he’d stick his leg in a trash can and fall to the floor. It was a typical GSD&M no-holds-barred effort: At least one art director on the team worked 150 hours in one week.

When informed about the way GSD&M was approaching the Southwest pitch, Stand Richards shook his head and said, “I would never, under any circumstances, be that abusive to my people’s time. The idea of separating one from his family for that significant period of time is unconscionable. Nor do I think a group stuck together for fourteen to sixteen hours a day in one room produces great work.”

The Warriors were unmoved. They put a photograph of Stan in the War Room to remind them of who the enemy was. “Don’t get me wrong,” says Spence. “I respect Stan a lot. But if he comes on my territory and goes after one of my accounts, I’m going to kick his ass.”

To win back Southwest, Spence and the other GSD&M partners—Judy Trabulsi, tim McClure, and Steve Gurasich—decided that the strategy of the new advertising should focus on the airline as a short-haul carrier, the leader in quick point-to-point flights. Their theme line: “No One Does Shorter Better.” Richards and Rod Underhill, the Richards principal in charge of the Southwest pitch, had thought about but rejected the short-haul positioning. “If a great opportunity presented itself to fly from Dallas to Atlanta,” says Richards, “then characterizing yourself as a short-haul carrier would no longer be valid.” Instead, believing that the advertising needed to show how Southwest bypasses the standard problems caused by flying other airlines, they went with: “We Help You Beat the System.” The opposing strategies would be a crucial factor in determining who would win the account.

Richards thought that GSD&M, with its different Southwest theme lines over the years (“Just Say When,” “The company plane”) had never clearly defined the image of the airline. Some Southwest advertising had been well received— GSD&M won several awards for a spot last year showing young employees goofing off in the boss’s office with a hula hoop and a globe, when suddenly the boss strides in, back on time, after flying Southwest. Yet, according to Jack Trout, a well-known marketing-strategy consultant from Connecticut who had been hired by Southwest to help judge the different agencies’ presentations: “The truth was most of it was unfocused. It was all over the sky and suffered from a lack of consistency.”

It was no secret at GSD&M that Southwest was unhappy with the content of some of the advertising and that officials at the airline felt that GSD&M, after having brought in larger national advertising accounts, was spending too little time on their account. (Southwest officials refused to be interviewed for this story, and Spence would not specifically comment about anything regarding the Southwest pitch). But in the month prior to the review, Richards kept saying that the chances of GSD&M losing the account were small. For one thing, Richards thought Herb Kelleher would never turn back on his friend Roy Spence. Industry scuttlebutt was that the purpose of the review was to shake GSD&M up.

Regardless, the Warriors wanted to overwhelm Southwest. They were led by Wally Williams, a 41-year-old associate creative director with a thick Texas accent and an offbeat sense of humor—for a Texas State Optical promotion offering two pairs of glasses for the price of one, he wrote a commercial in which a toddler heads for the bathroom with her mother’s glasses, drops them in the toilet, flushes, and says, “Bye-bye.” The warriors came up with such slapstick ideas as having pint-sized actor Danny DeVito pop out of an overhead storage bin on a Southwest jet to talk about the advantages of being short. Just like Richards, they devised a campaign based on stories of Kelleher’s childhood (in one commercial the football coach tells Herb to go long on a pass play and Herb replies that he only goes short). The Warriors even drew up a list of two hundred people who could be funny spokespersons for the airline. They worked in top secrecy. No trash was taken out of the building in case there were spies looking through their dumpsters.

Still, with ten days to go until the presentation, one senior creative leader with the agency now says, “I was worried that we didn’t have anything good. It hadn’t jelled in the way we were hoping. I looked at the campaigns and my feeling was, ‘Oh, shit. This isn’t going to do it.’”

More resolved than ever, the creative staffs of both agencies paced the hallways, blew on their cups of coffee, mumbled to themselves, doodled on notepads—all hoping for sudden inspiration. Tempers flared. In GSD&M’s War Room, more than one writer threw the food against the wall because the ideas weren’t coming. In Dallas, Richards executive Rod Underhill was heard shouting—in direct violation of one of Stan’s rules—“We’ve got to get off our ass!”

As part of the twentieth anniversary pitch, Richards himself thought up the idea of painting a Southwest jet with the signatures of Southwest employees—a takeoff on Southwest’s painting of Shamu on some of its jets. He also created, along with Rich Flora, a television campaign depicting cheerful Southwest employees at work. Richards’ tag line went: “At Southwest Airlines, there’s no question they do things very well. The question is how do they make it look so easy?” When the always-competitive Thomas Hripko heard it, he looked at Nadurak and said, coming close to sacrilege, “I don’t agree with it.”

Grant Richards, Stan’s good-natured, 31-year-old son and a creative head who will run the agency after his father retires, came in with a campaign showing worried executives from other airlines trying to figure out how to compete with Kelleher. And Gary Gibson and Doug Rucker invented a campaign based on the manic, Andy Rooney-like rumblings of Ian Shoales, whose rapid-fire commentaries are heard on National Public Radio. In one of Gibson and Rucker’s scripts, a scowling Shoales exposes the horror of being at an airport (“stuck in a hard plastic seat next to someone with a dripping chili dog and a boring story!”). Then the announcer’s voice explains how Southwest, with its few delays, keeps a traveler out of airports. The ad, even Hripko had to admit, was a winner. Gibson and Rucker just looked relieved that they had hit upon an idea. “I admit, we were starting to get real panicky,” says Rucker, “but we weren’t going to let it show.”

Three days away from the presentation, Richards’ calm manner returned during dress rehearsals. As each creative person read through his scripts, Richards would nod and offer his ultimate compliment—“I think that’s nice”—his voice as soothing as chocolate milk poured down a sore throat.

Instead of just choosing one campaign, Richards decided to present six campaigns to show Southwest the variety of work his agency could do. Included were two of Hripko and Nadurak’s approaches (the Ben Stein ads and “Herb’s Home Videos”), Rucker and Gibson’s Ian Shoales spots, the Little Herb commercials, Grant Richards’ commercials, and Richards own “they make it look easy” ads. The number of campaigns would be a key move in the final outcome. To prove to the Southwest board that his agency wasn’t all that stuffy, Richards arranged to get Southwest baggage-handler suits for himself and his creative teams to wear to the two-hour presentation. Outside the Southwest Airlines headquarters at Love Field in Dallas, Richards secured space on a billboard. WE’VE WAITED 19 YEARS FOR 5 PM, JULY 17 was all the billboard said, a cryptic reference to the time Richards was scheduled to make his presentation and a less-than-cryptic reference to his desire to win the account.

On the day GSD&M and Richards were to make their presentations (GSD&M would present that morning, Richards that afternoon), Richards called a final staff meeting. Richards, true to form, did not make even the slightest stab a pregame pep talk. (“I would never try to create an artificial spirit,” he says. “The best inspiration must always come from within.”) Though the tension was palatable—the younger guys looked as if they were losing their breath—Richards simply asked if everyone was ready. When they nodded their heads, he smiled kindly and said, “Okay, gang,” and walked out of the room.

GSD&M, however, was acting as if it was about to storm the beaches of Normandy. “I felt like Patton walking through the battlefield,” says Spence, “as he told his troops, ‘God help me, I love it so.’ In the middle of the night, I’d walk through this agency—there were papers scattered everywhere, people hard at work, the electricity flowing—and all I could say was, ‘God help me, I love it so.’”

True to his own form, Spence had come up with every dramatic ploy in the book. Secretly, in a room down the hall from the Southwest boardroom, where the agencies were supposed to make their pitches, members of Spence’s staff had created what Spence called the Strategic Air Command. The brought in a circular table with the Southwest symbol, a large pink heart, built in the middle. The put up black-and-brown paneling around the room and big television screens. There they would bring the Southwest review board for their presentation.

In Spence’s most daring gamble, less than a week before the presentation, he had spent the agency’s own money—some estimates, at least $100,000—to shoot and edit fifteen new commercials. During speculative pitches such as this one, agencies always use storyboards to show how their commercials would look. But Spence wanted GSD&M to be completely different. The Warriors had come up with a series of funny fifteen-second commercials—one showed three babies together, two crying and one laughing, with the announcer asking the viewers to guess which one of the three would end up working for Southwest Airlines—and there were also filmed testimonials from such Texas heavyweights as Henry Cisneros congratulating Southwest on its twentieth anniversary.

To demonstrate “The Power of One,” two chartered buses, filled with nearly two hundred GSD&M employees pulled up to the Southwest headquarters the morning of the presentation. All the employees were wearing T-shirts with “Together We Stand” printed on them. Some of the employees had highlighted out of that phrase with red in the words, “Get Stan.” Mysteriously, part of the Richards’ billboard was obscured by a large hand-lettered sign that read, “Good Luck, GSD&M!”

When Richards, back at his own office, heard about the billboard, he looked genuinely stunned. “That’s so high school,” he said gravely.

But that is the way the advertising business works: It runs on passion as much as it does on logic. For all the money and research and focus groups and marketing studies that go into creating an ad—for all the hours that a writer and an art director will spend to make sure the words are just right—the best advertising is usually nothing more than playing on an audience’s emotions. As Spence and the other partners made their presentation, the GSD&M employees quietly gathered in the lobby of Southwest’s headquarters. At the end of the presentation Spence, Wally Williams, Tim McClure, and Judy Trabulsi escorted Herb Kelleher to a balcony overlooking the lobby. As soon as they got there the GSD&M employees began singing “Stand by Me.” Yes, GSD&M went with a jingle, and Herb loved it. Spence and the others came running down the stairs, shouting and giving high fives, to sing with the group. Herb, moved by the display, began to cry.

When members of the Richards Group heard what had happened, they said, “We just lost.”

But at five that afternoon, when the Richards Group started its pitch, there was renewed hope. As Hripko read his Ben Stein commercials, Kelleher laughed so loudly that Hripko had to stop to make sure all the others could hear him. The review board also roared over “Herb’s Home Videos,” Little Herb, and Ian Shoales. Consultant Jack Trout said afterward, “Richards obviously demonstrated the most creativity of all the agencies involved. He was the most creative in using humor.”

That night the Richards group had its first company party ever in a little beer joint near Love Field. Stan, predictably, didn’t come. But everyone else was there, shaking each other’s hand, saying, “They loved it. They loved it.” But, the revelers knew the odds were against them. “Southwest wasn’t necessarily ours to win, no matter how well we did,” recalls Rich Flora. “We knew GSD&M would have to screw in their presentation for the account to actually move.”

The truth was that GSD&M did better than Richards in one critical area—the theme line. “when the positioned Southwest as the premier short-haul carrier,” says Trout, “they took the lead. Richards, with its ‘Beat the System’ theme line, showed what Southwest’s benefits were, but the never defined the airline except to call it different from other airlines. That wasn’t enough.” Moreover, says Trout, Richards made a mistake by presenting so many campaigns, “leaving a lot of us confused and distracted over which way he wanted to go. After GSD&M had finished, I said [to the Southwest board], gentlemen, this looks like a different agency than the one that used to work for you. Their work hangs together and it’s consistent. There’s no reason to fire them.” In fact, the board, without much hesitation, returned the account to GSD&M. In a prepared statement, Southwest said GSD&M was the “clear winner,” but GSD&M had agreed, in turn, to bolster the number of creative people working on the account and give Southwest more attention.

GSD&M had three parties over the next week to celebrate its presentation and victory. Spence had “Stand by Me” played over the company’s loudspeakers, and he barreled around the office pounding backs and shouting, “The Power of One, the Power of One!”

The morning after his presentation, Stan Richards and his staff were back in the office promptly at eight-thirty. The familiar hush had returned to the office. Stan’s young Turks were already busy on their other projects. Richards knew there would always be someone else knocking on his door (the week after he lost Southwest, he won the $10 million Whataburger account and soon after got the $6 million Memorex tape account.) But at noon, he gathered the entire agency for one last speech.

As usual he seemed unperturbed, faultless-looking, like the people one sees enjoying life in advertisements for luxury cars. “What an extraordinary performance I saw from you yesterday,” he began. “We have been absolutely a great agency over the last several weeks. It was a remarkable effort, and what resulted was brilliant work.”

He stopped and looked at his people. The air conditioner whirred overhead, emphasizing the quiet. “I want to say…” he stopped again, his eyes blinking quickly behind his glasses. Thomas Hripko, leaning against a wall, peered curiously at his boss. Could it be? Was the great Stan Richards actually close to tears?

Richards tried again. “Whether we won or lost doesn’t matter to me,” he said. “We accomplished much more than that.” Richards’ voice trembled, and for a few seconds he tried to calm himself. Finally, he said, “I just want to say that I’m proud of you all.”

And in the stunned silence that followed, the stoic aristocrat turned away, walked down a hall, and disappeared into his office, returning to his work.