This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

I close my eyes, and I’m back, stumbling up a goat trail, inching my way up for yet another look into Mexico’s Copper Canyon—the Barranca del Cobre—the jagged heart of the Sierra Madre Occidental. In my memory flicker visions of a canyon so deep and wide I never believed in it. Rock slicing up out of gorges. Green terraces clinging to mesas that waver like mirages. Land tossed in a prehistoric volcanic tantrum, seemingly uninhabitable. Yet if you look hard enough, the landscape is alive: from the corners of my eyes I had watched shy Tarahumara Indians move among the shadows of cave dwellings.

I visited the canyon only briefly, on and off during a two-week trip by train, by jalopy, and by horse, as I made my way from Chihuahua City through the canyon to Los Mochis, on the Pacific coast, and back again. After two weeks of travel and countless hours spent dangling my legs from ledges thousands of feet high, I still found the Sierra Tarahumara—10,000 square miles of mountain range that encompasses Copper Canyon—to be an unreal place, where the inhabitants sleep under the stars, walk barefoot in the snow, and run deer down on foot.

I had heard about the train trip with its spectacular scenery when I agreed to accompany a friend, Marita Hidalgo, to Copper Canyon and discover what lies off the tracks. The fifteen-hour excursion (the route is three hundred miles south of El Paso) merely skirts a great maze of barrancas; the six major canyons, together more than nine hundred miles long, would accommodate four Grand Canyons.

A hawk floats beneath us. The creaking of our saddles is the only sound.

Packing was troublesome. While the Sierra rises to twelve thousand feet above sea level, the bottom of the canyon is subtropical year-round. In the spring, days are warm but windy; summer brings bright mornings and afternoon thunderstorms; in the fall, you can expect torrential rains. Nights are always cool. We planned our trip for February, when the mountains would be cold, possibly snowy, but the Pacific coast would be balmy. I stuffed a backpack with ski clothes and light cottons, strapped it on, and hiked around my back yard by the light of a watery moon. “Yeah,” I thought, imagining I bore the weight of adventure, “I can handle this.”

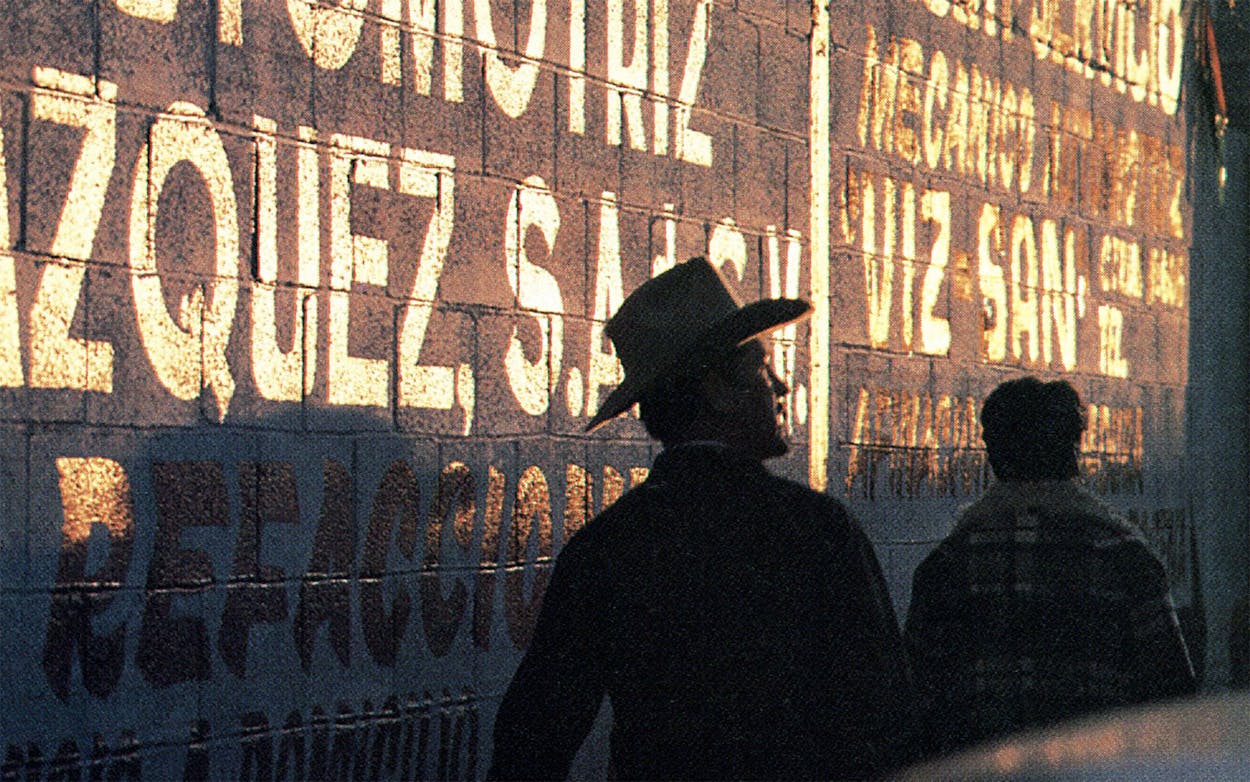

On the morning of our departure, we flew to El Paso, took a taxi to Juárez, and nibbled on black bass at Julio’s (where our lumpy baggage annoyed the maître d’). Having revved up our Spanish in dramatic discussions with both the taxi driver and the restaurant manager, we caught an Aeroméxico hop to Chihuahua City.

Chihuahua City

Altitude: 4650 feet

Volkswagen buses (combis) meet the planes and deliver travelers to hotels for about a buck. Marty and I are greeted by Johnny Rodríguez, the jefe of Viajes Dorados, the travel agency that planned our trip (it specializes in canyon excursions). On our tour of town we glimpse a Tarahumara woman crossing a side street, and we crane our necks to see her billowing muslin skirts—she wears at least three, each fully circular.

While in Chihuahua, a city of 480,000, we discover the carne asada and incendiary salsa at Los Faisanes (located at Periférico Ortiz Mena and Maryland). Huitlacoche crêpes, filled with a rich corn fungus as black and thick as shoe polish, are found downtown at Hostería 1900 (Independencia 903-B). Nearby, the Hyatt promises first-rate accommodations and even better people-watching. Herds of cattlemen favor the lobby bar’s bocaditos (“little bites” that you can easily make a meal of). Also of note on the culinary trail is the Café Galería Ajos y Cebollas (Colón 207), a bohemian hangout with divine squash-blossom quesadillas. Historical and cultural interests can be satisfied at the Pancho Villa Museum (Calle 10, Número 3017) and the Museo de Artes Regionales e Industrias Populares (Reforma 5), a fine, small Tarahumara museum with an adjoining crafts shop.

D Day

We are up at five in the morning, hoping to avoid any last-minute snafu that might come between us and the seven-o’clock train. At six our driver calls. Car trouble; we’ll have to take a taxi. We’re in the lobby at 6:15. The bellhop, pale with the cold, stares into the dark as if to conjure up a cab. The panic begins. Marty, who might be five feet tall when the wind is right, can be imposing when she stomps a foot. She demands that the hotel’s van driver be awakened. At 6:55 we make a two-wheel turn into the station.

We buy our tickets in two tediously slow rounds. By now, the station is fully awake, warmed by schooling crowds that seem in no particular hurry to board the train that is due to pull out in two minutes. A bandy-legged porter hefts our bags and waggles ahead of us to our reserved seats in a first-class coach. The car is empty; Sunday morning departures can be lonely.

Exhaling the last vestiges of hysteria, I watch my breath plume in front of my face. It’s freezing in the car. A burrito vendor stops to pile a sample of his wares, irresistibly warm, into my hands. A woman follows with a thermos full of café de olla, coffee brewed with cinnamon and sugar in a clay pot, which sets back my budget by 50 cents.

A hostess taps by in high heels, a gray wool suit, and a red tie, immediately curls up at the front of the car, and goes to sleep. The train schlumps forward and pulls out. I tilt back my gold-and-orange vinyl seat and let the coffee steam into my face as my feet grow numb. We glide from the station into darkness, our faces reflected in the windows. Before the sun begins to glow behind the mountains, Marty has tugged long johns on beneath her denim skirt, and I have added another pair of socks. The landscape grows lunar, with craggy silhouettes defined by peach-toned auras.

One of the hostesses—there are two, indistinguishable but for their hot-pink and hotter-pink lipsticks—gives us a packet of materials, the most helpful being a booklet by Johnny Rodríguez, which includes a kilometer-by-kilometer rail log. The light strengthens, the car begins to warm, and we plop down for a sunbath wherever the light puddles. I count four conductors in all, three in navy, the fourth in olive and a natty brass-brimmed hat. Outside, the glistening new blacktop that will parallel us most of the way to Creel snakes through fields of wheat, barley, corn, and beans, past corrals and pipeline. As we chug higher, desert vistas give way to scenes as familiar as the Hill Country.

When the train speeds into the first of 86 tunnels, Marty and I decide it’s time to lurch to the dining car and warm up some more. The heat is thick as we pass through one of the second-class cars, where almost everyone is asleep, blanketed bodies curled around bananas, tortillas, and boxes of crackers.

The dining car is years beyond down-at-the-heels, but I like the faded splendor of the red crushed-velvet banquettes, wooden Venetian blinds, and hefty pewter napkin holders. We sit down to menus that instruct, “Waiter not allowed to take verbal orders.” We stare at him. He stares back. Guiltily, we whisper our order. A decent plate of eggs, ham, and toast with juice and coffee costs less than $2 (the diner on the deluxe Express section of the train is set with linen and china, and slightly more-costly meals there are impressive). Slurping our coffee, we look up in time to see a lone campesino on a burro salute the train. Ranks of cornstalks stretch out forever behind him.

Cuauhtémoc

Altitude: 6750 feet

Once named for San Antonio de Arenales, Cuauhtémoc now honors the last Aztec emperor. It is the major city in what has been Mennonite country since 1921—50,000 Mennonites live around the city, on farms, and in tidy Germanic settlements called camps. Joel Quezada from the Viajes Dorados travel agency meets the train and leads us on a tour of a camp. Because Mennonites zealously preserve their faith and culture, few speak Spanish and all but the most liberal eschew modern conveniences. Horse-drawn buggies rock down the broad lanes that divide the sunny farm country into iron-fenced homesteads that have adobe houses topped by pitched metal roofs. A brood of grandmothers outside the general store wear embroidered head kerchiefs and full pinafores over homespun dresses.

We visit a remarkably unmechanized cheese factory (most of the cheese consumed in the state of Chihuahua comes from this area); browse through a typically spartan home, where handcrafted furniture is flush to the walls and numerous calendars are the only permissible art; and go into the one-room schoolhouse, in which a heavyset farmer in overalls and a gimme cap teaches math and history in High German. Little girls with big blue eyes and blond braids line up to sign my notebook in an old-world script. Finally, we lunch with Maria Peters, a rotund mother of nine. We munch on sticks of cheese, apple cookies, hunks of home-baked bread slathered with freshly churned butter and rhubarb jam, and—a treat shared from Peters’ own lunch—homemade pizza.

La Junta

Altitude: 6750 feet

Leaving the valley, the train crosses the Continental Divide for the first time. At the beginning of the Mexican Revolution, Pancho Villa camped nearby, often stopping trains. It’s a bright day but increasingly cold by the time we stop at La Junta, the last junction before we climb into the mountains. Vendors stream on board, a parade of children, each carrying a basket, a box, or a bucket filled with carefully wrapped food—cacahuates (“peanuts”), chiles rellenos, burritos, and tacos still warm from Mama’s griddle. They hawk their products singsong style; a tiny girl with the voice of a ballpark beer vendor triumphs over the others: “¡Ta-ma-leees!”

We sample everything. The fried chiles rellenos stuffed with cheese and wrapped in a flour tortilla are a delight. Egg-bread empanadas as broad as two hands are plump with sugared squash and pumpkin. As we eat, we watch the brass-hatted conductor run along the platform, as serious as the White Rabbit, his arms loaded with food.

The hot-lipped hostess stops by to say that the heat is being fixed, and sure enough, by the time we leave La Junta, my feet are warm. The train roller-coasters in and out of valleys, past mission settlements and muddy villages. The terrain no longer resembles the Texas heartland but rather Colorado, until with increasing numbers of apple orchards, it becomes Washington.

The somnolent hostess plugs in a Stevie Wonder tape and sings along before walking up and down the car with a bullhorn she never uses. By noon the heat we were grateful for in La Junta has us peeling off layers of clothing. The blacktop has dissolved into dirt, and buildings visible from the train are most often frontier towns built of notched logs and weathered planks. Scattered homesteads are simple—home to a family, one burro, and a handful of chickens. At San Juanito the brass-hatted conductor gets off, a single empty Coke bottle in his hand. He ducks into a mint-green log cabin and emerges polishing a full bottle. Standing on the open platform between cars, I smell the pines for the first time.

Creel

Altitude: 7700 feet

In 1930 the dirt streets of Creel marked the end of the line for what was known as the Kansas City, Mexico, and Orient Railroad. Much of modern Creel, a lumber-and-railroad town of 6500 people, looks like the set for Gunsmoke. In rainy summers or snowy winters, mud streets pull off strollers’ boots and mire jeeps. A jumping-off place for explorers, hunters, prospectors, anthropologists, and geologists, the town has the air of a last stop before great adventure, an outpost for buying provisions, securing guides, and spreading maps across wobbly tables. We hope to hire a ride to Batopilas, an eighteenth-century Spanish mining town at the bottom of the canyon.

Clouds climb the mountains around us as the rain pours. The roads muck up miserably. There is no way, we are assured, to get a vehicle down the logging roads into the canyon until the rain stops. Marty and I settle into fireside determination at our hotel, the comfortably modern Parador de la Montaña, downing margaritas of erratic quality as we eat plate-lapping T-bones. When the waitress timidly reports that the margarita mix has run out, we switch to rum. Hotel manager Lalo Miledi joins us to make sure we understand just what to expect from the inn in Batopilas. Nothing. No lights, no electricity, no restaurant, and, just possibly, no running water. And—he seems pleased to top that grim description—the woman who ran the place killed herself a week ago.

We escape Miledi’s crepe-hanging to slip and slide through town. Best discoveries: A great variety of side trips to waterfalls, missions, and villages is offered through Hotel Nuevo, a clean, spare $5-a-night hotel near the tracks; it also has a good restaurant and, incredibly, Donkey Kong. The Tarahumara Misión store, adjacent to the tracks, has a fine selection of Tarahumara handcrafts.

Getting Down

Juan, our driver, looks to be well over fifty and is nearly toothless and jolly to the bone. He arrives in a battered Wagoneer and explains that the 150-kilometer trip will take six hours. We will get there shortly before sunset, and if we wish to catch the train out of Creel the following day, we will have to leave Batopilas before dawn. Another couple of people from the Parador happily pay the going rate of $50 to make the hard trek with us. When Juan’s daughters squeeze in, we are seven, an unholy crowd for the long journey in a truck with no springs and with gasoline fumes billowing up through the floor.

The scenery soon eases our discomfort. When we make the first of many photo stops, Juan laboriously wipes all the windows and even our glasses. I am overwhelmed by the tumble of sunlight into the chasm, the tinkle of goat bells floating up from hidden ledges, the silver ribbon of river. More than once I spot the skeletal remains of a car scattered on a ledge far below. I understand why the Indians told the Jesuits that only the birds knew how deep the canyon might be.

After four and a half hours of soul-jarring travel, we stop beside a stream to picnic on white-bread sandwiches (I beg one of Juan’s burritos instead). While we eat, he opens the hood of the truck and forces various fluids into the engine, which has begun to sound like a lawn mower.

Once we’re back in the truck, the road slows its downhill rush and spirals into little more than a two-way donkey trail. Rounding a bend, we come upon a Tarahumara couple, who look fearful and back away to the brink of the canyon. The lowering sun shoots light through the woman’s red skirt. The bare-legged man wears a white loincloth, square across the rear, tied around his waist with a woven sash. Both have short-waisted blouses with full sleeves gathered at the wrist—a design introduced by the Spanish. The Tarahumara are not fond of strangers. We pay for our photos, but the man regards the coins we place in his palm as the worthless trinkets they are in a barter society.

Batopilas

Altitude: 1950 feet

Late in the afternoon we roll into a valley and across the bridge to Batopilas. The dirt road winds up into town, where it splits into two cobbled lanes. Banana and papaya trees brush the arched doorways of red-roofed, white colonial buildings. Two figures of Neptune trumpet from the lintels of a dry-goods store that has been in business since 1863.

Light is failing fast, and we have an hour before the shadows cast by the perpendicular cliffs overtake us. In no time, the town of seven hundred knows that we are here. We make our way to the river and the ruins of a vast hacienda that was built by the American owner of the mine that produced a bonanza of silver for more than two hundred years, our progress slowed by a chain of giggling little girls curious about the güeritas (“blondies”).

Meanwhile, Juan has asked the village priest’s housekeeper, who is also a freelance cook, to prepare a meal for us and has searched in vain for a key to the boarded-up inn. At last light, he decides we must break in. Ignoring the unmade beds, we scramble for the kerosene lamps. After downing a lamp-lit dinner of tuna surprise at the housekeeper’s place, we stumble back to the inn to tuck in. I sit for hours in the courtyard, listening to the river snore, tracing the path of a falling star, waiting for a reason to sleep.

Divisadero

Altitude: 9000 feet

Following a sharp descent into a loop where the railroad makes a complete circle to cross over itself, we climb steadily to Divisadero. The train will stop there for fifteen minutes as passengers scamper to a scenic overlook. It is the only place where the vast canyons can be seen from the tracks.

Tarahumara women, their skirts puddled around them, sit behind careful displays of wooden figures—carvings of long-headed men with horsehair beards, bats, moon-faced cats, and rats (“mouse eyes” is the ultimate Tarahumara compliment). Baskets woven of bear grass, palm, and pine needles, still fragrantly green, range from thumb-size to a foot in diameter. Most endearing are the fantastical violins, totally unmusical to my ears but lovely to look at.

The birdlike female vendors speak only if spoken to, except when softly singsonging in a dialect that sounds like Navajo. Their faces are broad and ruddy, their almond eyes usually downcast. I buy several baskets and strike up a conversation in halting Spanish with Catarina, a toothless young woman who seems old beyond her years. I ask whether she will trade a small basket for the bumblebee pin I am wearing. She squints at the older woman sitting beside her. The woman nods curtly, and Catarina quickly pockets the pin.

Adjacent to the overlook is the Cabañas Divisadero-Barrancas hotel, the only accommodations right on the canyon’s rim. Most of the log-and-stone rooms have spectacular views, private baths, rustic furniture, fireplaces, and cheery fuchsia-and-lime-green bedspreads (Marty, who determines the comfort factor of a room by its bedspreads, is pleased). We climb back aboard the train to make the five-kilometer run to Posada Barrancas del Cobre, the inn where we will stay.

Posada Barrancas del Cobre

We heave our bags onto a long wooden platform, turn around, and the train is gone. A hundred yards off, the Posada Barrancas is coddled by low hills; from it the canyon is a fifteen-minute hike. Recently acquired and renovated by Roberto Balderrama, the posada is a cozy place with beamed ceilings, fireplaces, and tiled verandahs. Simple meals included in the price of the room are served family style beneath wagon-wheel chandeliers. Roaring fires, creaky leather chairs, and oversized rockers in the adjoining lobby inspire sing-alongs.

We meet Arturo, our hiking guide, whose lanky legs set the pace on an easy trail that soon takes a turn for the sky. We learn the primary lesson of hiking in the canyon: walking is either up and down or not at all. Marty and I stop to examine every madrone and mountain laurel—any excuse to catch our breath—and Arturo asks politely if we are smokers. We climb behind him, sometimes on our hands and knees, as he speaks of mountain lions and coyotes. Near the rim, we hear a scream: “I hate this place! Get me out of here!” The woman’s words still echo when we pass two backpackers. The man’s teeth are clenched, the woman’s eyes damp. They disappear behind us.

We are determined to hike down to the Cueva de Chino, which is said to have been named for a Chinese railroad worker who lived there thirty years ago. For the last several years it has been home to fifteen members of one Indian family. On the narrow rock shelf, a young mother sits sewing; a crinkled man of eighty stares. Arturo assures us that they expect visitors (signs along the path had pointed the way), but I am reminded of the Tarahumara expression: “Only dogs enter houses uninvited.”

An overhanging ledge and leaning planks form the family’s single room. Water seeping from the rock is captured in a hollowed stone basin. A Quaker State oilcan functions as a stovepipe, while branches serve as hangers. Rock niches are for setting hens and for storage. Goats roam where they please. If wealth is measured in possessions, this family is the poorest of the poor, but from where I stand, the dipping sun paints the canyon walls with a rich man’s view.

The next morning we ride up the mountain to El Puerto, yet another lookout point. I ask the names of the woolly, stout-legged ponies that are our mounts. Cowboy Antonio stares as if I have asked the name of a luggage cart. Once again we climb, through meadows, past cornfields, clambering over boulders the size of small cars. The horses are steady, with a mule-train devotion to the lead pony.

The view is glorious. The canyon walls flare like ruffled skirts. Hawks float beneath us, and between breaths of wind there is no sound other than creaking saddles. We gaze into the distance through a telescopic lens. Would Antonio like a look at a rancho we spot some miles away? He shakes his head no. We ask why. “I’ve been there,” he says, scissoring his fingers in a walking gesture.

Bahuichivo-Cerocahui

Altitude: 5250 feet

Back on the train, we pause at San Rafael, then disembark at Bahuichivo. Met by the Hotel Misión bus (which doubles as the local school bus), we are bounced and battered until the vehicle halts to pick up a girl and an elderly woman, more spirit than flesh in her heavy black coat and scarf. Although all the seats are empty, the abuelita perches atop Marty’s luggage until the woman’s granddaughter, chagrined, tugs her into another seat.

I offer the little girl my tape player and headset. She declines, but the old woman turns to accept. She puts the headphones on and grabs her chest. “It makes my heart pound,” she says, smiling. Next time we stop, she asks, “¿Cuanto lo debo?” (“How much do I owe you?”), then disappears in a cloud of dust, the reggae beat of UB40 reverberating in her head.

After checking in at the Hotel Misión in the village of Cerocahui, we walk the cobbled lane to the school, where the students are cutting crosses from cardboard boxes with kitchen knives. Bashful, they introduce themselves by ancient, lacy names: Arminda, Estella, Rosamelia, Adriana. I distribute a round of balloons, teach the girls to make obnoxiously shrill whistles, and beat a retreat before the nuns take down my name.

Roaming about, we are beset by children offering guide services to a waterfall (several riding-hiking side trips can be arranged at the hotel), but I am more intrigued by the opportunity to watch a family butchering a cow. When they finish, sheets of translucent red beef hang on a clothesline (the makings of machacado, or chipped beef), while the beast’s skin lies sprawled in the dirt, flat as a rug.

At a comedor, a lunchroom in her home, a woman flaps her apron to send chickens flying out of the kitchen. She invites us in, graciously dusting off two vinyl-and-chrome chairs. Her name is Montserrat Chávez, and she chatters shyly about our hair and eyes and begs us to have a cup of coffee. Her walls are lined with jars of peaches, apricots, and chiles.

At the hotel, children play in the streets, until at dusk they fall silent with the birds. Seated at a heavily carved Moorish-style table with other guests—a family of sisters of all sizes, ages, and shapes—we dine on enchiladas by the light of a kerosene lamp (the operator of the town generator is ill). A twelve-year-old boy serenades us in a clear voice that brings tears to my eyes, and after dinner the sisters dance and sing. Marty and I retire to our room at last to stoke the wood-burning stove to a nuclear heat. We sleep like cats.

The Coastal Plain

The train ride from Bahuichivo to Los Mochis takes nine hours, but the scenery, outside the canyon proper, is the most spectacular of the entire journey (many travelers begin the trip at Los Mochis to catch the morning light on this leg of the journey). The railbed loops and spins. At Temoris (3350 feet) it’s hot—the sticky, tropical kind of heat that makes flowers bloom and people wilt. Unable to sit still, I join a couple of Mennonite boys on the rear platform to watch the tracks unfurl behind us. Later, still roaming, I stop between cars to discuss the mysteries of the canyon with a Japanese teenager who speaks Spanish. The wind is hot when it grows too dark for us to read each other’s lips.

Los Mochis

Altitude: 150 feet

Marty and I are exhausted when the train finally huffs into Los Mochis. It’s ten o’clock, and we’re starving, but fortunately the dining room of the Hotel Santa Anita (the flagship of the Balderrama hotels) is still open. Our spirits are revived by bowls of tortilla soup (chicken broth thick with goat cheese and swimming with chipotle peppers and tortilla strips).

In the morning we tour the city of 135,000 people, driving past modern mansions and the rambling brick homes of the old colony, composed of the city’s American founders. The sugar mill that started it all still belches black ash from December through June. Most interesting is the diversity of plant life. Many of the two thousand types of plants that the city founder imported for his botanical gardens, now in ruins, have taken hold throughout the city.

Best of all, we like the market, packed with everything from birdcages to bassinets, all beneath flapping flags. We try the local specialty, birria, which turns out to be baby goat cooked to mush, but we soon give up on mecoche, too-sticky swirls of taffy. Even after we can eat no more, we lust after radishes the size of apricots and onions that glow purple in the morning light. Eventually we succumb to the temptation of apple empanadas.

And then, because it seems the thing to do, we climb aboard the 6 a.m. train out of Los Mochis the next day and do the whole trip in reverse.

Getting There

Anyone thinking of doing Copper Canyon should bear in mind that the trip, while absolutely worth the effort, sometimes is a bit rough. Inexplicable delays are not uncommon, and you should take a spare sandwich and drink in case the food runs out. Dress comfortably.

Tour agencies can arrange your entire trip, which guarantees hotel rates and rooms at the better places. If you book personally, you might not get a room if there’s a crowd and you might pay more. On the other hand, package deals aren’t the cheapest, and they limit flexibility. Incidentally, the exchange rate for the peso has recently been more than a thousand to the dollar.

As for the train, nervous travelers should reserve a day or more in advance either personally or through an agency. However, usually you can get tickets the day you leave and at points along the way.

Departure: Texas National Airlines (512-826-1162) flies direct from San Antonio to Chihuahua City daily for $120 one way, $240 round trip. Aeroméxico (800-237-6639) flies from Juárez to Chihuahua for $39 one way; from Los Mochis to Juárez the charge is $62.

Many travelers start in El Paso. If you do, you will need to take a taxi to Juárez. Our U.S. taxi to Julio’s restaurant (at 16 de Septiembre and Americas) was about $20; a Mexican taxi from there to the Juárez airport is $25 to $30. Airport vans at Juárez will make the transfer to El Paso for $12 per person on the way back.

Train tickets: Train reservations may be made through the Hotel Santa Anita, travel agencies, and tour operators or directly by writing or calling Chihuahua Pacific Railway, Box 46, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico. To call, dial 011 (the international code), 52 (the code for Mexico), 14 (the city code for Chihuahua), and the six-digit local number. The numbers for the railway are 12-22-84 and 12-38-67. In Chihuahua, the station is at Méndez and Calle 24. A round-trip train ticket is $18; deluxe accommodations on the Express are $32 one way. Note: the ticket agent must also be advised where the client will be getting off and on the train. He will mark the ticket on the back with dates and places.

Tour Operators: Baja Adventures, 16000 Ventura Boulevard, Suite 200, Encino, California 91436; 800-543-2252 (also serves as advance reservations agent for the Express).

Viajes Dorados, Aldama 316, Despacho 6, Apartado Postal 1145, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico; 16-22-84 (the travelogue Chihuahua and All Points West, by Johnny Rodríguez, is available from this address for $2).

Caravanas Voyagers, 1155 Larry Mahan, Suite H, El Paso 79925; 800-862-2345.

Pan American Tours, Box 9401, El Paso 79984; 915-778-5395.

Sanborn Tours, Box 761, Bastrop 78602; 800-252-9650.

Hotels: Hyatt Exelaris Chihuahua, Avenida Independencia 500, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico; 16-60-00.

Reservations for the Balderrama hotels—Posada Barrancas, Hotel Misión, and Hotel Santa Anita, the best accommodations in the canyon—can be made through the Hotel Santa Anita, which also offers train packages. Contact Hotel Santa Anita, Los Mochis, Sinaloa, Mexico; the city code for Los Mochis is 681; the hotel numbers are 2-00-46 and 2-04-08.

For reservations at the Parador de la Montaña in Creel, write or call Parador de la Montaña, Allende 114, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico; 12-20-62 or 15-54-08.

For reservations at the Cabañas Divisadero-Barrancas, write or call Aldama 407-C, Box 661, Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico; 12-33-62 or 15-11-99.

Barbara Rodriguez is a freelance writer living in Austin.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads