This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

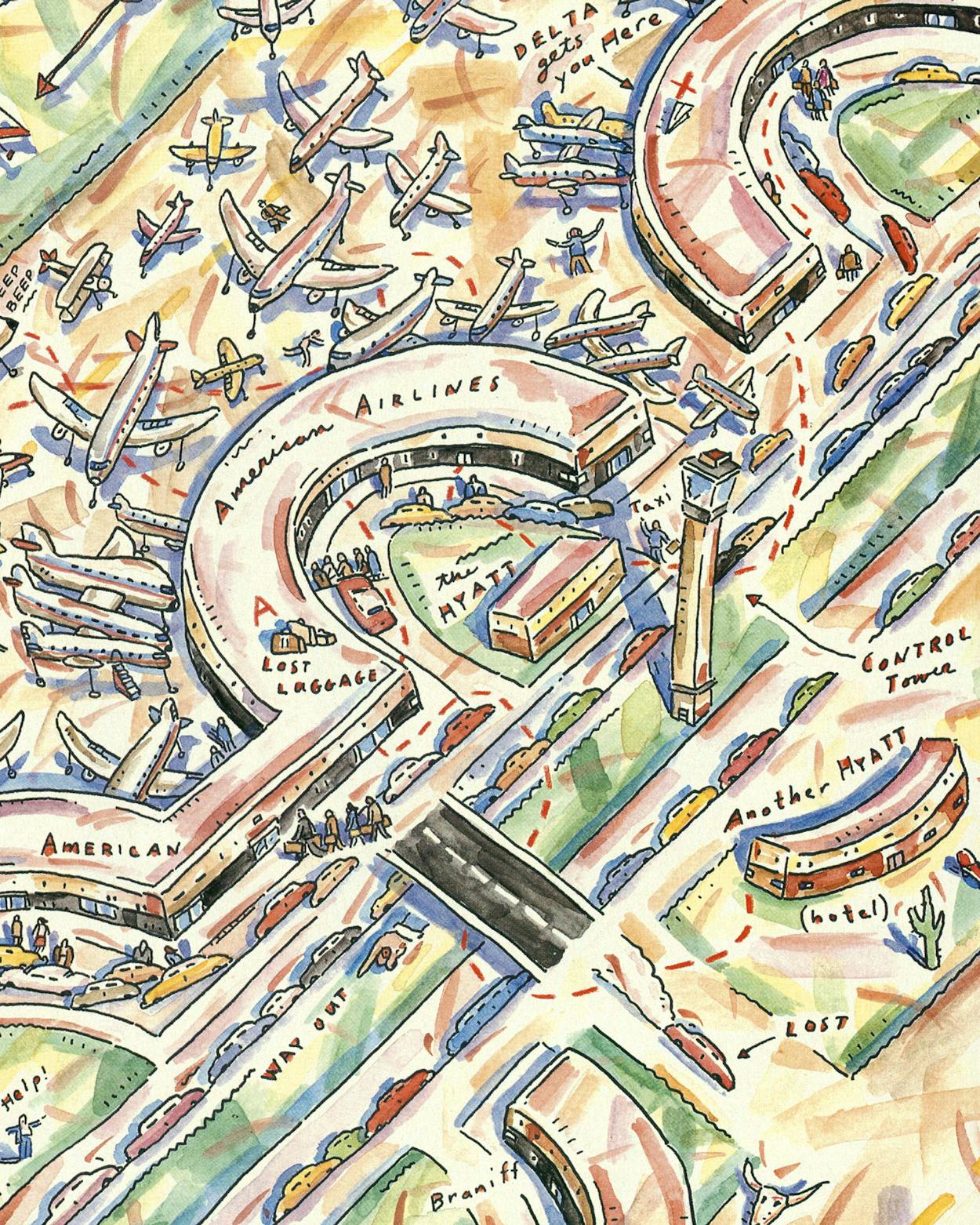

When the Dallas–Fort Worth International Airport opened in 1974, it was touted as the biggest, most sophisticated airport in the world. But in recent years its stardom has been sullied by stigma. Everybody has a story to tell about having to cool his heels in a DFW waiting area because of a missed or delayed flight, and nobody will ever forget the Delta 191 crash that killed 137 people on August 2, 1985. DFW now has a reputation to live down.

Truth be told, the most accurate picture of DFW fits neither a 1974 nor a 1985 extreme. Airline deregulation, the Federal Aviation Administration, and nose-to-nose competition between giant carriers American and Delta have made the airport another beast altogether. And to the question “What is DFW becoming?” the answer is multiple choice: Service at DFW could get slower, scarier, or it could get smoother, safer. Much depends on whether the FAA upgrades its radar system. Ultimately only one thing is for certain: DFW, even as you sit there at the gate or pace aimlessly through the concourse, is getting busier.

The first thing that you need to know about DFW is that although the airport’s design is not exactly obsolete, it has a serious flaw. Built as an origin-and-destination airport, it must now function as a hub. Translation: DFW was built to get passengers from their cars to their planes as rapidly as possible. The distance from curb to ramp is among the shortest in the world, which is nifty, except that nowadays two thirds of the 40 million passengers DFW handles each year are just passing through. They never set foot outside the airport. Semicircular terminals, so right for origin-and-destination traffic, can bog down connections critical to a hub facility.

Hub airports are the child of deregulation, which in 1978 dictated that the most efficient way to move vast numbers of passengers from A to C was via B. Deregulation places a premium on flight frequency as well as on making sure a passenger stays on-line, or starts and finishes his trip on the same airline. Hubs are the best way to accomplish both ends. They suck in flights from places like Shreveport, Louisiana, and College Station, divvy up their contents among other flights, and shoot them off to destinations like Los Angeles and New York. DFW is now the fourth-busiest airport in the world—as a hub, and there’s the rub.

The second thing you need to know is that 90 percent of the planes that hub at DFW do so on the east side of the airport. That’s where Delta and American are based. Next year Delta is scheduled to complete a nine-gate satellite on the southeast side of Terminal 4E. When that is finished, Delta will field some three hundred flights a day. In the not-terribly-distant future, archrival American will stage four hundred departures a day—all from its Terminal 2E-3E complex. Not only is DFW American’s busiest hub, but also the carrier’s national headquarters are just a few miles down the road, lured from New York City in 1979 amid the howls of Mayor Ed Koch.

While the west side of the airport isn’t exactly a ghost town—it accommodates Braniff, Northwest, United, and a slew of other carriers at Terminal 2W—the airport’s lopsided growth on the east side inevitably means more delays. Norm Scroggins, the manager of DFW’s radar control tower, explains the east-side dilemma: “We will be dealing with a significant congestion problem in competition for the space we have over there.” Others in the tower add that it doesn’t take a genius to see that a ninety-ten mix doesn’t make for the most efficient use of the airport’s 17,800 acres. The solution is obvious too, though it’s not necessarily a sure thing. It depends on whether American follows age-old advice: go west.

The answer to consumer and controller prayers is a proposed project that American is calling 5W. The idea is that American would add sixty gates on the Fort Worth side of DFW. Rather than repeat the mistake of the east side, American’s terminal would mimic Atlanta’s Hartsfield terminal, a modern hub design. The addition would lack the curvilinear grace of DFW’s pre-deregulation terminals, but it would be the essence of efficiency. Three rectangular piers would be connected by people-mover cars, passengers would have to walk no more than five hundred feet from gate to gate, and layover time would be substantially reduced. One hang-up: Construction costs could reach $750 million. American is still weighing its options.

Money aside, a lot of American’s hesitancy has to do with what could happen once it vacated the east side. “If we should choose to move over there,” says Mike Gunn, the airline’s senior vice president for marketing, “we are presenting ourselves with some competitive risks by freeing up the old terminal.” One of Gunn’s fears is that another airline could penetrate the port, making DFW a hub for three carriers.

The problem with that is the industry maxim, “Two’s company, three’s a crowd.” Two-carrier hubs work for airlines and passengers alike, providing just enough competition to keep the other guy honest. Ménages à trois, however, inevitably turn messy. With three-carrier hubs, so many seats are flying around up there that airlines are forced to lower fares suicidally to fill their seats. Braniff, once one of DFW’s dominant carriers, learned the lesson the hard way in the early eighties. Continental, Frontier, and United had a similar go-around at Denver’s Stapleton Airport a couple of years later; Frontier ultimately foundered. Today there are no true three-carrier hubs in the United States. And while American could presumably thwart an interloper at DFW, should someone be so brash, no airline’s dominance can be guaranteed forever.

The real threat is from Delta, DFW’s number two airline. It is playing a full-out we-try-harder game. The Atlanta-based carrier commands 25 percent of the passenger traffic at DFW, compared with American’s 57 percent. Delta, going back to the heyday of Love Field, has proved to be a major player in Metroplex aviation. Now it aims to increase its DFW presence markedly; Delta is gunning for a 35 to 40 percent share of the market. American’s vacating of 2E-3E would give Delta all the room it needed. Such a shift—American to 5W and Delta to former American turf—would result in a rebalancing of the airport, one that could only help the passenger.

The third thing you need to know is that DFW’s mega-snafu is not necessarily the tower’s fault—not now anyway. Despite the bad rap laid on air-traffic controllers as a species, delays are actually down at DFW. Recently the airport’s radar control tower won an award as the best in the country. The airport tallied 1,466 delays in August 1986. For the same month this year the figure was 386—a 74 percent reduction. Contributing to the improvement were moves by American and Delta to spread out their chronological clusters of arriving and departing flights. Although flights are still bunched up for quick connections, the actual arrival and departure times found in airline timetables are now a lot more realistic than they were at this time last year. The new schedules recognize that you can shoehorn only so many airplanes into so much airspace without making somebody late. The schedule changes were prompted in no small part by pressure from a Transportation Department that is sick and tired of impossibly long lines of planes waiting nose-to-tail to take wing. Frequent fliers call the game “tarmacking.” Their intake of aspirin and antacid increases proportionally to how fervently the sport is played.

Despite the improvement, the tower will be taxed to the max and delays will soar once more if traffic continues its upward spiral. At least one knowledgeable FAA controller predicts that by the turn of the century DFW will be the busiest commercial airport in the world. “One of the things you have to look at,” says DFW controller Ron Uhlenhaker, “is that we set a new traffic high here probably once every two weeks. It’s almost routine.” Last year the airport handled nearly 576,000 takeoffs and landings. By 1991 the figure could hit 863,000. Something has got to give. In an interim report the FAA predicts that the “inability to handle the increasing complexity and traffic demands . . . will lead to delays that ultimately threaten the growth and stability of the aviation community serving this area.”

Terminal troubles are something the FAA will leave to the airlines. Its priority for now is a proposed $69 million Metroplex Air Traffic System Plan, which would in effect increase DFW’s available airspace. The money would have to come from the federal government. And in these days of record deficits, funding is anything but assured. “Money is one of the problems,” concedes Uhlenhaker.

Because God made just so much sky, even over Texas, about the only way to produce more airspace is to create it electronically. Specifically the FAA plan calls for the relocation of four electronic “fence posts,” which define the region’s airspace, and the addition of two more. These VORs (very-high-frequency omnidirectional radio-range navigational stations) would make room for more traffic by doubling the airspace controlled by radar. The FAA would add a third radar station to the two it already has to cover the area defined by the VORs.

An important plank in the FAA plan calls for “segregation of performance characteristics,” which in more earthly parlance means making sure that a Boeing 727, with an approach speed of 135 knots, isn’t on the same approach path as a twin-engine Cessna, whose landing speed is perhaps 35 knots slower. “Where you make your money,” says controller Uhlenhaker, “is in getting everybody doing the same speed on final approach. It’s much like the freeway. When everybody goes down the freeway at fifty-five, you just hum right along. But if you put somebody in the middle of that doing twenty-five, you begin to create a problem very quickly.” The way things are now, the FAA routinely mixes aircraft of varying speeds. Central to the remedy: two additional runways designed specifically for commuter and corporate aircraft. Each runway would be six thousand feet long and dovetail precisely with FAA ideas about separating big jets from small feeder liners. “The east commuter runway is already part of the master plan,” says the airport public information director, Joe Dealey, Jr. “We could begin construction as early as 1988.”

And that again brings us to the crux of the challenge: funding. Controllers and carriers are poised to tackle the future, the FAA with its $69 million plan and American with its $750 million west-side proposal. As a record number of passengers prepare to mob the airport during the holidays, DFW must make a choice: bite the fiscal bullet or choke on the fruits of its own success.

Jerome Greer Chandler, author of Fire and Rain: A Tragedy in American Aviation, is a contributing editor for OAG/Frequent Flyer magazine. He lives in Anniston, Alabama.

How Other Texas Airports Stack Up

Wondering how the other major airports in the state compare with DFW? The Federal Aviation Administration says it tracks delays for the nation’s 22 large “pacing” airports. In Texas, that means only DFW and Houston Intercontinental. Delay figures are not available for Austin, El Paso, San Antonio, Houston Hobby, and Dallas Love Field. Since these airports usually function as origin-and-destination spokes, though, they are less likely to hold you captive than their big brothers, the hubs.

Austin Robert Mueller Municipal Airport

Mueller handled the 97th-largest volume of passengers in the world last year—3.63 million people. In terms of takeoffs and landings, the FAA ranks it 68th in the United States. On November 3 Austin voters rejected a proposition that would have authorized the city to upgrade Mueller with a new $1.1 billion runway and terminal—an expansion that would have further encroached on black and Hispanic neighborhoods surrounding the airport. On a separate proposition, Austin voted in favor of spending $728 million in airport system revenue bonds on a new airport twelve miles northeast of town. The downtown Mueller ultimately will be closed. As part of the “Move It” package approved by voters in November, Mueller is authorized to make $30 million in stop-gap improvements so that ground and air traffic will be more manageable until the new airport opens for business, perhaps by 1995.

Dallas Love Field

For now, Love is an operation strictly for one carrier—Southwest. Bound by a bill sponsored by U.S. Speaker of the House Jim Wright, Love can field commercial flights only within Texas and the contiguous states. Despite the restriction, Continental wants to make Love a spoke and compete with Southwest on the Houston Hobby run. In handling 5.45 million passengers last year, Love ranked as the world’s 68th-busiest airport. The FAA tabbed it as the 43rd-busiest in the nation. Love got a face lift this year with some striking exterior-trim work on its thirty-year-old terminal. In addition, a badly needed new parking deck is nearing completion. Officials say it could be ready for the Christmas rush.

El Paso International Airport

Last remodeled in 1979, the airport has had the same sixteen gates for nearly twenty years. Despite El Paso International’s being only ten miles from the Juárez airport, travelers wishing to fly into Mexico must either drive across the border to the Juárez terminal or fly to DFW for a connection. El Paso is the nation’s 88th-busiest in takeoffs and landings, slightly below San Antonio. But it is 123rd in the world in passenger volume, with 2.4 million travelers last year.

Houston Hobby Airport

Once-moribund Hobby is back on its feet again. In passengers handled, last year it ranked 55th-busiest in the world—7.49 million fliers. For takeoffs and landings, it is the nation’s 37th-busiest airport. Recent upgrades at Hobby include improvements in the ticket lobby and gate areas. On the downside, Hobby lost its only real hub carrier when TranStar folded earlier this year.

Houston Intercontinental Airport

The world’s 26th-busiest field, Intercontinental handled 14 million passengers last year. In terms of takeoffs and landings, the FAA ranks it the 34th-busiest airport in the nation. The airport’s delay tally is a bit worse for the first eight months of this year than for the same period in 1986. The FAA says that Intercontinental averaged two delays per one thousand takeoffs and landings last year, six per one thousand this year. The home base for ever-expansive Continental Airlines, the airport opened a 10,000-foot runway this year and is in the process of designing a $75 million eleven-gate international terminal.

San Antonio International Airport

The world’s 67th-busiest airport took care of 4.66 million passengers during 1986. In terms of takeoffs and landings, the FAA ranks it the 83rd-busiest in the country. Three years ago the airport doubled its gate space with the addition of Terminal 1. The old structure, Terminal 2, remains in use. Improvements to prosaic interior are the news of the day at the airport. An FAA control tower opened two years ago, and a new cargo facility is on the drawing board.

J.G.C.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Dallas