When a personal habit or attitude starts showing up with fair regularity in your dreams, I suppose you have to consider it ingrained for better or worse. Not long ago, after a latish supper involving cornbread, raw onions, black-eyed peas cooked with cayenne peppers and fat salt pork, and some leftover chocolate mousse, I had a mild nightmare about being closely pursued from building to building of a shattered city by a squad of alien soldiers dressed in queer medieval uniforms but armed with automatic rifles. While scrambling on all fours through the rubble, I came to a crater in which were exposed some broken electrical lines with attached conduit connectors and service-entrance heads and other such equipment. And despite the urgent hostile voices and footsteps behind me, and my fear, I stopped and began prying things loose and unscrewing them and ramming them into my pockets. They were much too good and useful to be left behind.

While I’ve never come close to attaining that degree of parsimony in waking life, I can alas discern in myself such a tendency as the years progress, and I know pretty well where it comes from. Its main source undoubtedly is the fact that I’ve led a country life during most of the past two decades, for among us brethren of the ruddy neck, savingness and salvage have never lost their currency, a main theme I will come back to presently. It derives too from having been a writer for thirty years, not highly productive and only occasionally salaried; such a rogue specimen learns early in the game that for him any economic system is a jungle red in tooth and claw, and he either gets used to the idea of living sparely and making do with little when he has to, or else finds a more comfortable direction for his energies. And farther back still, this miserly tendency is rooted in experience with some fairly hard times in the thirties, when I was growing up.

I can’t claim truly proletarian origins, but during my late childhood and adolescence one would have needed tunnel vision and a quite rudimentary brain to stay unaware that things were very tough around and about, and to see extravagance as anything but a path to trouble and woe. Furthermore, a continuity with past human experience still existed strongly in those days, and my people like most other clans had collective remembrance of even harder times in country places and small towns, tracing back to Reconstruction, to the rich but frugal frontier, to the Old World and its ways. There were wasters and spendthrifts among us, but not many. People hung onto what they had, if they had anything, and trash collectors in our town had much smaller loads of stuff to worry with than members of that calling do today.

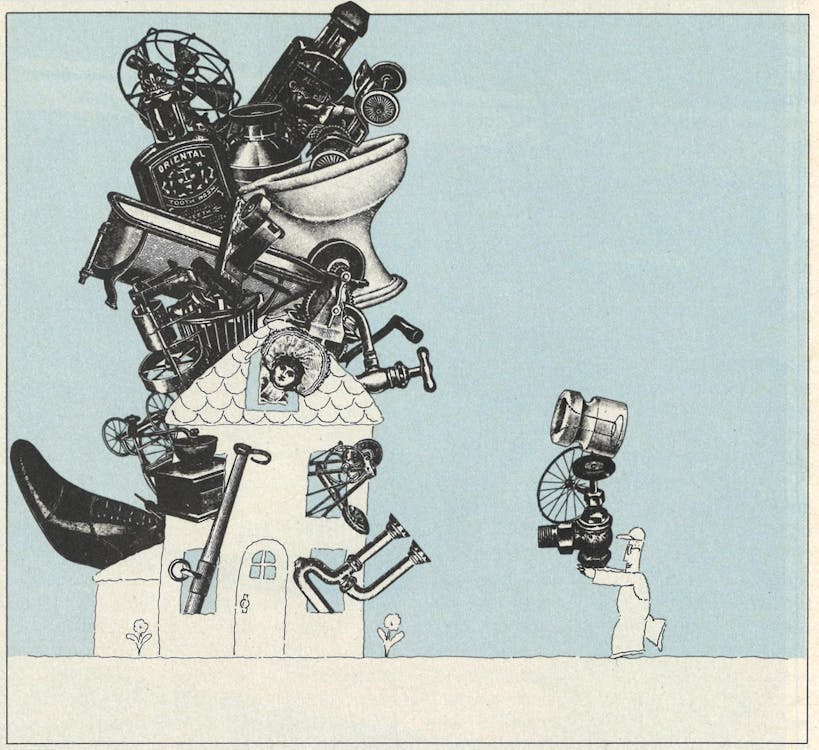

On the other hand, as citizens of a land that was still rather lavishly endowed with good things despite its occasional bouts of economic constipation, neither were most of us much inclined toward compulsive scrimping and salvaging, which we tended even during a depression to view as humorous. In our funny papers we had the Toonerville Trolley’s Old String Saver to laugh at, and in my neighborhood we had a quiet gentleman who suddenly conceived a passion for used jars and bottles, which he could not bear to throw away and indeed fished out of other people’s garbage cans on frequent sorties along our alleys with a burlap sack, wearing a double-breasted suit and a tie. They stood in serried, sparkling, multicolored ranks on shelves he had built for them along his back fence, outlined his flower beds and walkways, filled a disused servants’ room attached to the garage, and finally started creeping on little cat feet into the house, at about which point his family (bottles not being the only problem) committed him to the veterans’ mental facility at Waco and hired two elderly black men with a mule and a small beat-up wagon to tote off the vitreous accumulation. These haulers worked at their task for two or three days, chiefly because they were a bit touched with bottle mania themselves and handled and loaded every item tenderly to avoid breakage, which took some doing with a springless iron-wheeled vehicle.

Our amusement over something like that was nonetheless a bit wry, for we recognized it for what it was—just a funhouse-mirror magnification and distortion of the old waste-not-want-not frugality in which a majority of us Americans then believed, whether or not we practiced it consistently. We were laughing at ourselves, and at the rural past that underpinned our ways.

World War II marked the end of those times and the apparent end of some other things too. In the economy of throwaways and planned obsolescence that evolved after it, wastefulness became a national virtue, a force that kept factories and businesses humming and created both jobs and wealth. It created a lot of pleasure of a sort also, freeing the general population from old restraints like a preacher’s pretty daughter turned loose in a strange and delectably sinful city, though marvelously there was no need to feel guilt. Buying a new Thunderbird you didn’t need with money you didn’t have, you could if you wished work up a glow of righteousness over your part in helping to maintain—nay, increase—the GNP.

In recent years, of course, doubt has replaced a good many people’s righteous glow as the price of the gallon of gas that will propel a T-bird about nine or ten miles down the pike edges up toward six bits, erstwhile desert raiders grow richer than Texans, heat sometimes fails to gush from heating ducts, rivers and even breezes smell bad, and fish sticks arrive at table impregnated with tasty carcinogens. Our tenure in sinless Eden begins to seem less assured, and here and there among the fruit trees stand prophets calling themselves environmentalists, ecologists, post-industrialists, and other things, who assert loudly that there really is guilt after all. They cry out, these spoilsports, for a return to thriftiness on a grand scale—for husbandry of resources, for scrimping and patching and saving, for salvage and reuse, which in current prophet language are known as recycling.

Well and good, an aging rustic observer thinks. Very well and very good, in fact, and high time it was for such ideas to grab a hold. But in his naive mind there is a glimmer of the déjà vu: he puzzles over whether there is really much difference between these rather modish activities mobilized beneath the banner of ecology, and a lot of ancient practices and attitudes that have limped along with our species through the centuries under a crude tattered ensign labeled Need. Men have always rejoiced in extravagance when luck permitted, from primitive yahoos harrying entire herds of bison over a cliff for the sake of a few steaks and chops, to modern suburbanites generating x pounds of rich garbage per head per day and vacationing in Las Vegas. But that sort of luck has been rare, and the salient economic traits of the bulk of humankind through history have been thrift and stingy inventiveness, which still rule supreme across most of the earth’s curving crust.

What he wonders, our bucolic déjà-viewer, is whether the present uproar doesn’t just mean that the tortoise is catching up with the hare, that some age-old gritty facts of life are getting ready to reassert themselves against the prodigal way of being that a few Western nations have been able for a time to afford.

For in rural regions of even the Western world those facts have never ceased to exact homage. At rare and uncertain intervals farmers and graziers have managed to gather a little of boom’s largesse along with their city cousins, but more normally they have had to watch from afar, wistfully or at times with rage, the major harvest of cash and its attendant fun and games. While most care enough for their life on the land to stick it out there if they’re able, large numbers of them, especially among the small-timers, have been forced to leave by an inability to pay for the high-priced goods and equipment they either need or have been seduced into buying, and often also by the rebelliousness of wives and offspring who find the antiseptic and fun-filled world they see on TV preferable to the labors, stinks, and simplicities that a country existence traditionally entails.

Survivors therefore are likely to be types who have chosen sturdy mates and are willing to work at outside jobs when country income dwindles. They also have a high immunity to the charm of expensive shiny machines and gadgets, and above all they are imbued with the old rural instinct and ability to patch and salvage and improvise and substitute whenever possible, instead of buying. Frugality has never gone out of style for them; they wear it like a much-darned sweater.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in marginally productive country like these rocky cedar hills where I live, and in no way is it better shown than in the hill dwellers’ prevalent attitude toward materials that an industrial society gone mad regards as trash, waste, junk. What much trash amounts to around here is a potential defense against the demons of a hostile economy; it serves not only to repair one’s machines and other possessions and to keep them usable but also to fabricate new ones. One or another kind of it fits into tractors, implements, buildings, plumbing systems, fences, feeders, or elsewhere, and if it doesn’t fit anywhere it probably has some wondrous new country usefulness of its own, just waiting to be discovered. Hence the durable forms of it are seldom treated with the contempt they get in cities, where they’re tossed out to be whisked away by municipal employees for destruction or burial at distant sites, but are saved—often cherished—and given new purpose when occasion arises.

In truth it sometimes seems that the ability to accumulate junk and to utilize it ingeniously is a measure of true countryness, not only among natives but also among part-timers like me and even some of the well-heeled city people who for a good many years have been buying and fixing up old homestead tracts in our hills, at first for weekend pleasure and then, as fascination progresses, for use as stock farms or mini-ranches. With these latter the use of trash may begin as an amusing way to emulate local picturesqueness—old tractor seats made into patio stools and so on—but it generally gets more earnest as they discern what a fathomless pit of expenditure the improvement and working of a country place can be unless you learn to cut corners. And when they start being proud of their junk, like the rest of us, they are snared for good.

I lately examined a fine cordwood splitter devised and constructed by a friend of mine. Among its components were a five-horse air-cooled engine from a wrecked lawn mower, a hydraulic pump from a Case tractor, a long-stroke piston out of the landing- gear system of a World War II bomber, two lengths of railroad track, a massive riving wedge made from old plowshares welded together, and various other hunks of metal gleaned from car frames and elsewhere with a cutting torch or a wrench. Such mechanical complexity is beyond my own modest powers, but I found it admirable, just as its maker understands my pride in more rudimentary creations like water troughs fashioned from the galvanized drums of big cable spools, and a Dionysian grape crusher with rollers made out of lengths of leftover plastic sewer pipe, some pulleys and bearings from a worn-out washing machine, and a handle off of a busted meat grinder.

Bomber parts and cable spools and railroad iron are obviously not run-of- the-mill rural refuse. Neither are crossties, public urinals, car drive shafts and axles and engine blocks, used telephone poles, oil-field sucker-rods and drillstem pipe, anchor chains, high-line brace cables and earth screws and eyebolts, howitzer wheels, fire-escape ladders, street-paving bricks, signboards, janitors’ sinks, steel barrels, landing mats, and a good many other sorts of technological detritus that find their last, sometimes bizarre employment out here among us hayseed inheritors. With them we supplement our local sources of trash, which are often meager precisely because of all the indigenous frugality and the repair skills that keep things functional practically forever.

We find them in the automotive cemeteries, junk and wrecking yards, war-surplus emporia, and other cluttered trash havens of the cities, where so much discarded treasure finds a resting place. On trips to town we may browse for hours in favorite establishments of this sort, like bookworms on the quays of Paris, emerging most often with a few irresistible artifacts in the beds of our pickups, acquired for a pittance and perhaps not even needed now, but far too good to pass up. Without this copious fountainhead of exotic refuse I am sure we would feel deprived, as some apolitical Korean and Vietnamese peasants—crafty junk-utilizers, both breeds—must have felt when the prodigious flow of GI waste slacked off in their respective lands. Maybe we would form our own cargo cults as certain Melanesian tribesmen have done in hazed recollection of war’s richness, awaiting with drums and prayer and a rattling of boar-tusk bracelets the airborne return of the lavish alien god John Frum.

Singing my song of trash, I sense the onset of shudders in more aesthetic readers, who may recall having seen country dooryards where defunct cars and appliances and large objects of rusty iron vie with lilac bushes and shade trees for an observer’s attention, and who conclude that such scenes must be the inevitable effect of a fascination with junk. It is not so. True, some collectors do get to thinking that their prizes are pretty all by themselves, but their wives seldom share the belief, and most country junk awaits its time of resurrection in repositories out of sight of the house. My own supply, for instance, is divided between an area behind the barn, where heavy or “valuable” things molder in dignity, and our household dump in a stabilized gully across the creek, where more portable and ordinary pieces rear up out of a sea of cans and glass and plastic and crumpled baling wire. (Shamefully and unecologically, we burn most paper and such, though organic kitchen waste goes to the garden to be plowed under like manure.) But it’s there if I ever want it, and even if I can’t always find a needed item by delving into my own assortment, I can often cadge one or trade for it—the swap being another prime element in rural thrift—from out of a neighbor’s hoard.

As for the deliberate decorative use of junk qua junk, once common in our Texas countryside, it has fallen off sadly in recent decades as homogenized electronic sophistication has infiltrated people’s consciousness. I refer to such things as yard fences made from dummy practice bombs or landing mats or bedsprings or cultivator wheels, and flowerbeds ringed with old truck or tractor tires painted red, white, and blue. Examples of this kind of work are rare enough now that I get a nostalgic twinge from their sight, and though I know very well that a current vogue in the use of native natural materials like cedar poles and limestone is in far better taste, I still sometimes find myself missing certain striking monuments to the conviction of junk lovers that trash is glorious stuff. One of these was the home of an obviously vigorous and probably Rabelaisian family in a small Central Texas town I used to pass through on trips. At the perimeter of its lot was a ten-foot levee of tamped, sodded earth on top of which they had embedded a parapet of old stoves, refrigerators, washing machines, and toilet bowls, these last being filled with artificial flowers. It was something to look forward to, but my last time through I saw that they had moved away and a bulldozer had flattened their fortress.

Those of the rest of us who let our affair with refuse escape from the realm of its utilitarian value, mainly manage now to confine the visible result to a knickknack shelf or two full of old cough-syrup bottles, rusty spurs, harness buckles, fragments of Model T Fords, shed deer antlers, and other such delights found here and there on our property. But there’s always danger the thing can get out of hand. A couple of years ago, after planting a little vineyard, I started looking ahead to its time of productivity and told a few city friends of gourmet bent that I’d appreciate their saving wine bottles for me. They did so with a vengeance, and at present their response lies several layers deep in a small separate shack we call “the bunkhouse’’ and has invaded a side room of our residence. The accumulation is causing uneasiness in the family’s senior female, but as for me I find all these jewellike, flat-bottomed bubbles of glass exquisite, quite aside from their intended usefulness. I soak off their labels, wash them until they gleam and glitter, dry them upside down in a rack, plug their mouths with tissue against dust and web-weaving spiderlets, and then sort them according to hue and shape—burgundy, claret, rhine, or italianate oddball—before stowing them away in compartmented cartons liberated from a liquor store’s garbage.

As the stacks of cartons grow I find myself gloating over them, and only now and then do I wonder idly who it is, far back in the mists of my youth, that I remind myself of.

- More About:

- John Graves