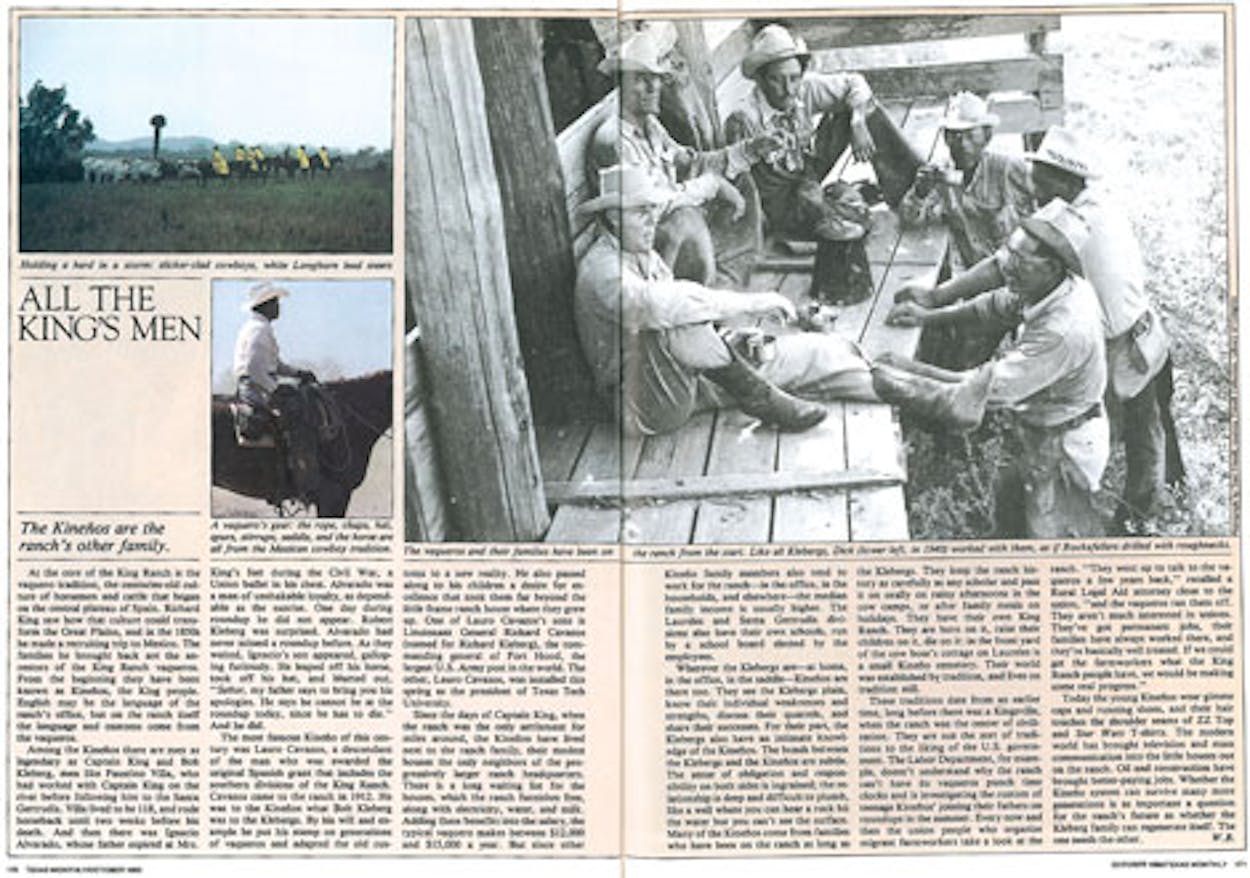

At the core of the King Ranch is the vaquero tradition, the centuries-old culture of horsemen and cattle that began on the central plateau of Spain. Richard saw how that culture could transform the Great Plains, and in the 1850s he made a recruiting trip to Mexico. The families he brought back are the ancestors of the King Ranch vaqueros. From the beginning they have been known as Kineños, the King people. English may be the language of the ranch’s office, but on the ranch itself the language and customs come from the vaqueros.

Among the Kineños there are men as legendary as Captain King and Bob Kleberg, men like Faustino Villa, who had worked with Captain King on the river before following him to the Santa Gertrudis. Villa lived to be 118, and rode horseback until two weeks before his death. And then there was Ignacio Alvarado, whose father expired at Mrs. King’s feet during the Civil War, a Union bullet in his chest. Alvarado was a man of unshakable loyalty, as dependable as the sunrise. One day during roundup he did not appear. Robert Kleberg was surprised. Alvarado had never missed a roundup before. As they waited, Ignacio’s son appeared, galloping furiously. He leaped off his horse, took off his hat, and blurted out, “Señor, my father says to bring you his apologies. He says he cannot be at the roundup today, since he has to die.” And he did.

The most famous Kineño of this century was Lauro Cavazos, a descendant of the man who was awarded the original Spanish grant that includes the southern divisions of the King Ranch. Cavazos came to the ranch in 1912. He was to the Kineños what Bob Kleberg was to the Klebergs. By his will and example he put his stamp on generations of vaqueros and adapted the old customs to a new reality. He also passed along to his children a desire for excellence that took them far beyond the little frame ranch house where they grew up. One of Lauro Cavazos’s sons is Lieutenant General Richard Cavazos (named for Richard Kleberg), the commanding general of Fort Hood, the largest U.S. Army post in the world. The other, Lauro Cavazos, was installed this spring as the president of Texas Tech University.

Since the days of Captain King, when the ranch was the only settlement for miles around, the Kineños have lived next to the ranch family, their modest houses the only neighbors of the progressively larger ranch headquarters. There is a long waiting list for the houses, which the ranch furnishes free, along with electricity, water, and milk. Adding these benefits into the salary, the typical vaquero makes between $12,000 and $15,000 a year. But since other Kineño family members also tend to work for the ranch—in the office, in the households, and elsewhere—the median family income is usually higher. The Laureles and Santa Gertrudis divisions also have their own schools, run by a school board elected by the employees.

Wherever the Klebergs are—at home, in the office, in the saddle—Kineños are there too. They see the Klebergs plain, know their individual weaknesses and strengths, discuss their quarrels, and share their successes. For their part, the Klebergs also have an intimate knowledge of the Kineños. The bonds between the Klebergs and the Kineños are subtle. The sense of obligation and responsibility on both sides is ingrained; the relationship is deep and difficult to plumb, like a well where you can hear a rock hit the water but you can’t see the surface. Many of the Kineños come from families who have been on the ranch as long as the Klebergs. They keep the ranch history as carefully as any scholar and pass it on orally on rainy afternoons in the cow camps, or after family meals on holidays. They have their own King Ranch. They are born on it, raise their children on it, die on it: in the front yard of the cow boss’s cottage on Laureles is a small Kineño cemetery. Their world was established by tradition, and lives on tradition still.

These traditions date from an earlier time, long before there was a Kingsville, when the ranch was the center of civilization. They are not the sort of traditions to the liking of the U.S. government. The Labor Department, for example, doesn’t understand why the ranch can’t have its vaqueros punch time clocks and is investigating the custom of teenage Kineños’ joining their fathers on roundups in the summer. Every now and then the union people who organize migrant farmworkers take a look at the ranch. “They went up to talk to the vaqueros a few years back,” recalled a Rural Legal Aid attorney close to the union, “and the vaqueros ran them off. They aren’t much interested in unions. They’ve got permanent jobs, their families have always worked there, and they’re basically well treated. If we could get the farmworkers what the King Ranch people have, we would be making some real progress.”

Today the young Kineños wear gimme caps and running shoes, and their hair touches the shoulder seams of ZZ Top and Star Wars T-shirts. The modern world has brought television and mass communication into the little houses out on the ranch. Oil and construction have brought better-paying jobs. Whether the Kineño system can survive many more generations is as important a question for the ranch’s future as whether the Kleberg family can regenerate itself. The one needs the other.

- More About:

- King Ranch