The headquarters for one of the hottest independent oil companies in Texas right now is a tiny, one-floor storefront on Route 16 in Graham, next to a Colonial grocery store. On a glass panel at the front entrance is a rendering of a pump jack that looks like a grasshopper. That’s the company symbol. The name of the company is Cresoper—rhymes with “grasshopper —Oil. Company president Alvin “Red Dog” Creswell had wanted to name the company Leo Oil, because Leo is his astrological sign, but vice president Darrell Creswell, Alvin’s 26-year-old son, objected. “I always thought pump jacks looked like grass-hoppers,” Darrell says. “Besides, Leo Oil doesn’t sound very classy.” Company president bowed to the wishes of his vice president on that one. Company investors don’t care what the name is so long as company president and vice president keep doing what they’ve been doing: namely, finding oil like there’s no tomorrow.

The Creswells struck oil last September, long after the boom had turned to bust, and they’ve been hitting it ever since. At the latest count they were up to nineteen straight winners without a miss, including one 2100-barrel-a-day gusher and other wells that can produce 1280, 600, and 200 barrels a day.

At least, that’s according to their latest count. I should mention right up front that there are any number of people who are not completely convinced that the Creswells have been quite as successful in the oil field as they say they’ve been. Like about half the town of Graham, for instance. (Darren Creswell chalks that up to small-town jealousy.) Drilling reports at the Texas Railroad Commission also tend to cast a bit of doubt on the nineteen-in-a-row claim. (Darrell attributes that to government bureaucracy and the difficulty of keeping up with red tape. “It takes two weeks to drill,” he says, “and six months to do the paper-work.”) But whether or not the Creswells’ claims are a mite exaggerated, you have to agree with Red Dog when he says, “We did pretty lousy during the boom. And we’re doing pretty good now that there’s a glut.” Even taking the Railroad Commission records at face value, they are still raking in over $20,000 a day. Not bad for a couple of guys who were broke this time last year.

We met for lunch in Graham one recent afternoon —Darrell, Red Dog, and myself. Actually, it wasn’t just the three of us. There were about a dozen people, most of them company investors, sitting around a table at K-Bob’s Steak House, next door to Cresoper Oil, where the Creswells usually have lunch. And actually, you couldn’t tell they were investors, not at first anyway. They were generally older men, most of whom wore open-collar short-sleeve shirts, and 1 just thought they were retired guys who liked hanging around the Creswells. But Red Dog and Darrell both assured me that they mem, indeed, bona fide out-of-town investors, and Darrell later confided that he and his father could hardly get over to K-Bob’s anymore without there being a few investors around to join them.

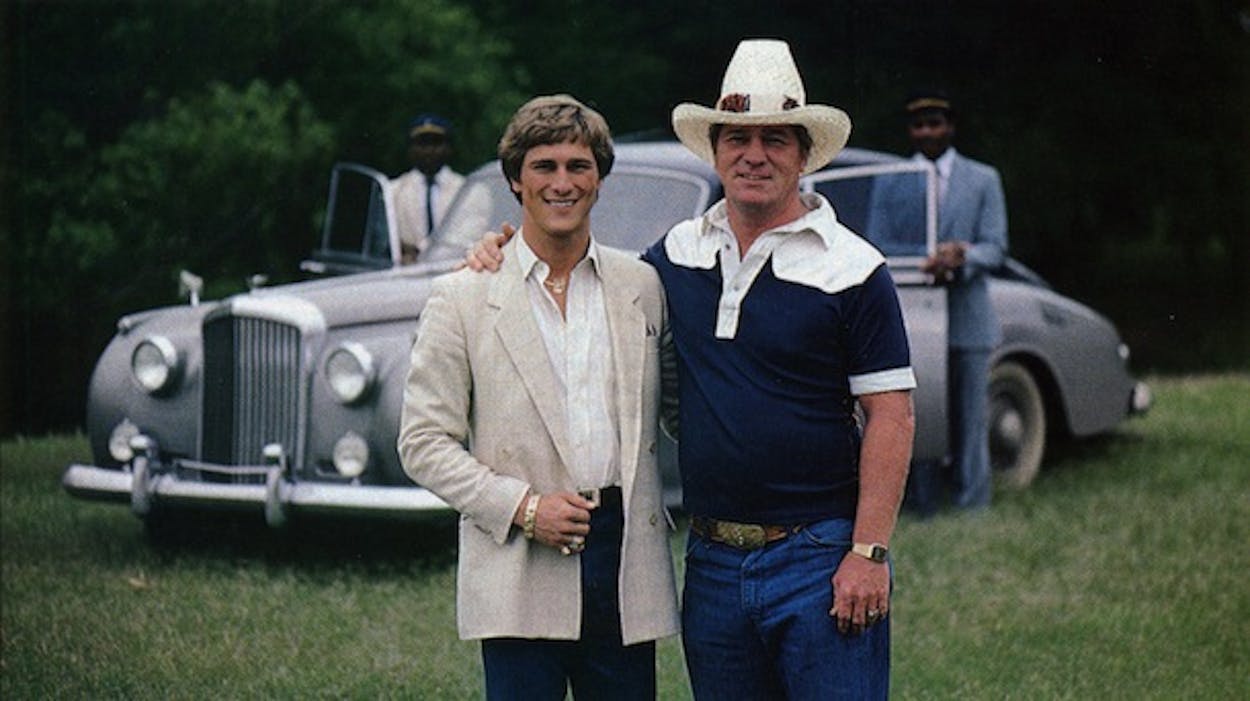

Seated next to me was Darrell himself, looking like nothing so much as a cocksure young man who had just struck it very rich. He was bedecked in gold jewelry of the most ostentatious sort, including a gold necklace that had a pendant in the shape of five oil derricks. “This stuff is all real,” he told me as he flashed his various rings and bracelets. Next to Darrell was one of his two chauffeur-bodyguards, a young black man named Harold Jackson. Harold’s main duty was to drive Darrell around town in Darrell’s vintage blue and silver Rolls-Royce.

Across the table sat Red Dog Creswell. Unlike his son, there was nothing about the elder Creswell that betrayed his new status as a wealthy man. He is 45 years old, of medium height and build, with a stomach that hangs a good bit over his belt and hands that are dirty and callused. On this day he was wearing faded jeans, boots, a grimy shirt, and a large black cowboy hat. Between bites of steak, he proceeded to tell me about his rise in the oil business.

“I’ve always wanted to make money, and over the years I tried to make it in a bunch of different ways,” he began. “Why, once, Darrell and I got into smuggling sugar over the border from Mexico. We were doing pretty well at that for a while.”

About eight years ago Creswell decided that his best chance to get rich was the oil business, so to that end he moved from El Paso, where he had been a Full Gospel minister and an exterminator, back to Graham, where he had been born and raised. He had long harbored a plan to find oil in Graham, and now he was going to give it a shot.

“Have you ever heard of the old McCloud well?” he asked. “They drilled that well in 1928, right up the road here. When it came in it was the biggest well anyone had ever seen around here. It came in at twenty-five thousand barrels a day.” The trouble was that the McCloud well blew out before it ever produced any of that oil, and despite fifty years of trying, no one had been able to get at that oil again. Red Dog Creswell wanted to give it another try.

Creswell began buying up acreage around the McCloud well. It was very cheap—he paid between $10 and $30 an acre even during the boom times—because no one thought oil would ever be found there. And for his first seven years in the oil business, Red Dog didn’t do any better than his predecessors. Whenever he got enough money together, he would drill a well, but it was usually dry. He went broke twice. Once, he struck oil, but his creditors took over the well. He was, in sum, a poor man just barely getting by who had a dream that everyone else in Graham thought was completely nutty. But Creswell refused to let the dream die.

Early last year Red Dog enlisted the aid of his son to raise money for him. The two of them began doing business as Cresoper and started dreaming the dream all over again. Darrell won’t divulge his money-raising secrets, but soon the company had enough for a serious drilling program. And this time their luck changed: they hit oil. How many times they hit oil, of course, is a matter of some contention in Graham, but this past February they hit a well no one could dispute—the 2100-barrel-a-day gusher. Red Dog is convinced that he is tapping the same oil as the original McCloud well. “They say that the oil from that well was real hot. Well, the oil from our wells is pretty hot too.”

How did Creswell succeed where no many others had failed? Here we bump up against that element of this story that makes the skeptics, well, skeptical. Frankly,’ Creswell’s geology is a little suspect. He has no geological background himself, and at first he didn’t even hire an explorationist to help him decide where to drill. “I had faith in Jesus,” he said. “I had a preacher come out here. He looked around, and he told me, ‘God has said that there is a lot of oil in this area.’ And sure enough, that preacher was right.”

Creswell also claimed to have faith in creeks. “I call it creekology. I’ve always noticed how the closer a well seemed to be to water, the better chance it had of hitting oil. So I’ve always tried to drill close to a creek.” Within the last six months, Cresoper Oil had hired a real geologist, but neither the company president nor the vice president seemed to take his work too seriously. “Whatever he tells us,” said Red Dog, “we do the opposite. That usually works.” Darrell, in explaining his father’s success, said simply, “He just feels it.”

By then, lunch was over, and we were ready to head back to the office. None of the investors made a move for the check, so Red Dog signed it like he always does. On the way out the door Darrell told Harold to wait by the Rolls because they were going to Fort Worth in a few minutes. When we got to the office, Darrell showed me a map of the area surrounding Graham. It was filled with dots that represented attempts to drill wells. “See,” he said, pointing to a dot, “this is the McCloud well. And these”—he pointed to dozens of dots around the spot—”are all the dry holes people have drilled trying to reopen that well. And here’s us,” he said, marking off the various Cresoper wells, all of which were in that same vicinity.

Just then his father walked in the room with one of the investors. ”Here’s where I’m going to drill next,” he said to the investor. He pointed to a spot on the map slightly to the northeast of most of his other wells. “Do I have a royalty on that property?” asked the investor. “You berths,” said Red Dog Creswell. They both laughed.