This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

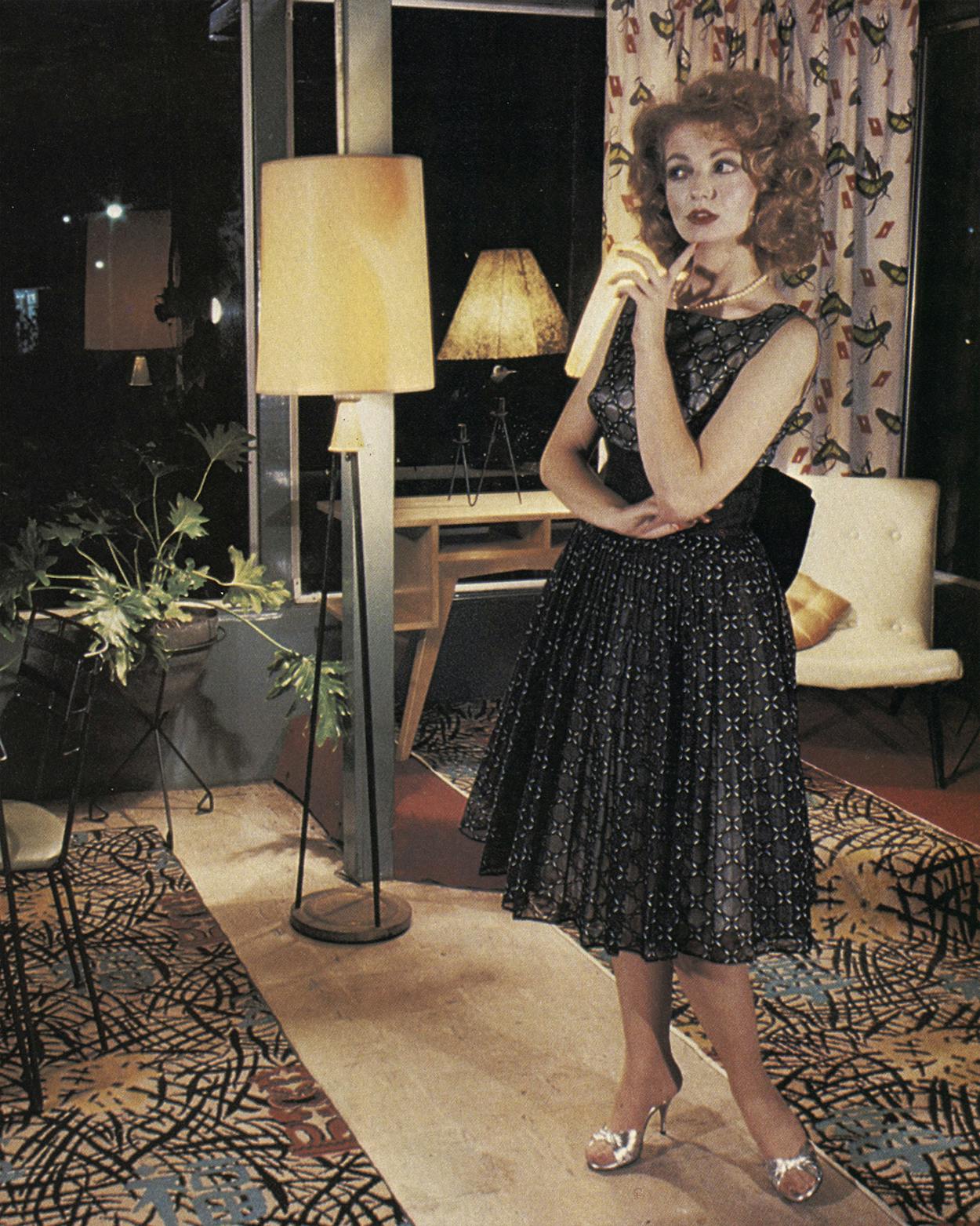

It was a generation that loved Lucy, Hula Hoops, poodle cuts, pink shirts, white bucks, and blue suede shoes. There were tail-finned Cadillacs, souped-up hot rods, ducktail haircuts, ponytails, pop beads, and Raleigh coupons. Headlines centered on the cold war, Khrushchev, Joseph McCarthy, commies, and fallout shelters. Living rooms were filled with the latest in wrought-iron butterfly chairs, nubby-weave sectional sofas, and blonde wood boomerang-shaped coffee tables. Beatniks, Rosemary Clooney, Johnnie Ray, and 3-D were hard to swallow, but Alka-Seltzer gave quick relief.

Fabulous or not, the fifties are no more; they’ve gone the way of the flapper and the tin lizzie. What is surprising is that now, two decades later, people have stopped turning up their noses and have started to take the decade seriously. We took a long, hard look at what was happening then—particularly in the design world—and we were amazed to see how well it all hangs together. Any decorative period that’s worth its salt has a name: Victorian, Empire, Art Nouveau, Art Deco. Belatedly, then, we christen the era that reached its height in the fifties as: Art Yucko.

But first a word of explanation: the fifties and Yucko did not start in 1950. No, they started on August 6, 1945, the beginning of the end of World War II. When the mushroom-shaped clouds cleared and peace came at last, the industries that had been expanded by the war found a new and voracious market in the American consumer. As industry stopped making bombers and started making butter dishes, a fascination for technology in the home spread like Parkay. The homey, overstuffed, frumpy look of the forties was out. Slick, modern, and up-to-date was in.

As the decade progressed, new materials bombarded the market. Boltaflex, Spongex, Texfoam, Vellon, Styllon, and of course the ever-popular polyester made their debuts, and “Floor-ever Vinylite Plastic” meant the whole house could be wall-to-wall modern. Lurex fabrics came in glowing colors with heavenly Wunda Weve textures and patterns. Molded foam rubber bounced into being, cushioning everyone’s life. Kids everywhere were stuck on Silly Putty.

Melmac made turquoise plastic table settings the only thing to have, and Tupperware parties became a national pastime. On the Art Yucko furniture scene, molded plywood, Masonite, Lustrex, and fiberglass were introduced, and wrought iron became the rage, praised for its lightweight durability and clean lines. As for wood, gentlemen preferred blonde, plastic-coated if at all possible. When furniture became waterproof, burn-proof, and alcohol-proof, it was all the proof that the American consumer needed: plastic was the modern way.

The push for the new wonder synthetics came from several directions, and one of them was space exploration. Though Sputnik didn’t happen until 1957, by the early fifties space was on everyone’s mind; people were looking up, not back. Inspired by this, designers launched furniture for the average pad. Star-dazed shoppers set their sights on heavenly interiors at down-to-earth prices. Outer-space motifs spread like wildfire as light fixtures looking like UFOs were found hovering in kitchens and antennas loomed from TVs like small satellite-tracking stations. The boomerang, another streamlined shape whose form mimicked its “orbit,” sped into the suburban home in the guise of ashtrays, coffee tables, and sectional sofas.

In the Art Yucko era, space was the new fad. There were rocket bodies on cars, skinny spacecraft legs on tables, and UFO eyes on sunglasses. The fifties was obsessed with the future, and the look to cultivate was uncluttered, technological, and modern.

Flying saucer and boomerang shapes were superseded by what may have been the most popular design motif of all Art Yucko: the structure of the molecule. This Tinkertoy shape, consisting of toothpick-like rods with knobs on the ends radiating from a central core, showed up everywhere, from wall clocks to fabric. Variations on the theme could even be found in the spindly-legged, wrought-iron tables and chairs that are almost synonymous with the fifties.

In its zeal to forget the unstylish past, Art Yucko occasionally ran rampant. Its designers paid lip service to the style dictum that “form follows function,” but overenthusiastic manufacturers incorporated the trappings of modernism into everything, whether or not they fit. Shapes that were fine for coffee tables were showing up in light fixtures, and rocket tails were being incorporated into automobile fenders. It was a sham: kidney-shaped lamps did not shed more light, and cars with fins didn’t go faster. Assembly lines filled the market with purely symbolic versions of modernity. The result was the twilight zone of fantasy function.

Function was not the only thing about Yucko that was fantasy. Much of the time, so was the value. Art Yucko design was an easy gimmick for people whose main concern was concept and not quality. It was ideal for those—maker and buyer alike—who wanted the essence of modernism and were willing to overlook mediocrity. The premise of streamlined design—anything you can do, I can do slicker—yielded to a new competition—anything you can do, I can do cheaper. At the zenith of Art Yucko, quality seldom went in before the name went on. One publication actually advised shoppers to discreetly kick the wrought-iron furniture when they went buying; if the paint flaked off, the price should be cheap. Art Yucko was a mass-produced look that could be everybody’s because The Price Was Right.

But whether or not it was tacky and tawdry, Art Yucko was in, and it stayed in for a very long decade. By 1952 national approval extended all the way to the White House. When Eisenhower was elected president, it seemed only natural for the press to refer to the White House as Mamie’s “dream house” and “Ike’s place.” Though hardly an American beauty, Mrs. Eisenhower rose as the sweetheart of pink, and Mamie pink became the new way to think. The First Lady of Yucko also inspired removable Mamie bangs and curls. The American public could understand a first family who dined on TV trays in front of the television. They liked a president who played golf while making policy decisions that were within range of the average mind.

By the end of Ike’s second term in 1960, though, the American sponge had reached the saturation point. It was the end of one era and the beginning of another, and Jackie Kennedy was reportedly appalled when she saw Mamie’s pink bedroom. Out went the Art Yucko drapes and rubber trees and in came antiques and Jackie’s impeccable taste.

When the newly redecorated White House was shown on TV, families everywhere took a critical look at their living rooms and said, “We’ve got to get rid of this stuff.” The trappings of Yucko somehow did not fit as well in Camelot as they had in the dawn of the atomic age. Technology was becoming less fascinating and more threatening, and people grew weary of their homes looking like a set for a Japanese space movie. Their fantasy-function furniture seemed sterile next to new antique reproductions. Homemakers forgot how much they had once liked their boomerang sectional after they saw their neighbors’ new Italian provincial living room suite. Eleganza!

The resurgence of nostalgia in design did not finish off Art Yucko, though; it only transformed it. That period of style exists no more, but the American love for mass-produced crapola flourishes. The living influence of Art Yucko can be seen in the vacuum-formed plastic Mediterranean consoles and crushed velvet sofas in the furniture palaces of America. Art Yucko was the way we were—and still are.

An Art Yucko Day

Saturday, Somewhere in the Fifties

8:00 a.m. As their dreamy new Philco clock radio clicks on to the tones of “How Much Is That Doggie in the Window?” our Art Yucko couple cheerfully begin another wonderful weekend. Taking the Spoolies out of her hair, the “better half” heads for the kitchen, where she chases a Metrecal cookie and a 1-A-Day vitamin with a glass of Tang. Our hero can’t face a poached egg, so he just has a cup of Maxwell House (good to the last drop).

9:10. Flipping on the console TV, she exercises with Jack LaLanne, then slips into her favorite black pedal pushers, pink Ship ’n’ Shore blouse, gold Cappezio flats, sprays her hair with new, self-styling Adorn, and hurries to the garage.

10:00. Tossing the family poodle in the backseat of their new Plymouth (with neato black and white Leatherette seats), she is on her way, as “Three Coins in the Fountain” blares from the radio. After dropping the poodle off at Bark ’n’ Curl, she has to rush to make her appointment for a permanent and lash dye at Chat ’n’ Curl (this is like Bark ’n’ Curl, only for women).

10:30. Meanwhile, Dad has donned Bermuda shorts, primed his crew cut with Dep, and is mowing the lawn.

2:30 p.m. Her hair freshly done in—what else?—a poodle cut, she stops at the supermarket. She throws chicken pot pies, Jell-O instant pudding and pie filling, V-8, and Campbell’s chicken noodle soup into the basket, edging ahead of a woman with two grocery carts and five children in coonskin caps.

3:15. Picking up her own kids from the roller rink, she cruises into the driveway (crushing a Hula Hoop on the way).

4:20. Now that hubby’s finished cleaning out the garage, he’s listening to two ball games—one on the radio and one on TV—while downing a six-pack of Pabst Blue Ribbon. She notices there’s not much time left to make a salad for the covered-dish supper tonight, so she chooses a quickie: “Simply combine lime Jell-O with stuffed olives, walnuts, and one can of English peas, chill, and serve.”

7:15. The babysitter arrives, late, popping gum and brushing her ponytail. She puts her stack of 45s on the hi-fi and phones ten friends as soon as the squares have left.

7:30. While the girls at the covered-dish supper eye each other’s creations (pineapple-chicken Hawaiian, Spam and Velveeta hors d’oeuvres on toothpicks, mock curried baked beans, and carrot and raisin salad), the guys file out to the garage to see the new Thunderbird. During supper the men discuss I Led 3 Lives, beatniks, juvenile delinquents, 3-D, and baseball, while the women talk about the sack dress, beehive hairdos, and Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher.

11:20. Arriving home, they are not thrilled to find the kids watching The Twilight Zone with the babysitter and her boyfriend.

Midnight. While he snores, she smears Noxzema on her face, wraps her hair in toilet paper, and hopes that they can get up in time to make the late service at church.

Cindy Bell and Mickey Troncale are Art Yucko enthusiasts living in Austin.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Architecture