This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

In preparation for the ninth annual Bass’n Gal Classic, the world’s premier bass fishing tournament for women, Rhonda Wilcox, a first-time contestant, wondered if she should take speech lessons. It was her husband, actually, who had come up with the idea. Bill Wilcox had just undergone a vasectomy, which he thought would go a long way toward helping Rhonda’s fishing career, and now he told her, in the thoughtful way he has with his wife, that the 33 women who qualified for the world championship probably would be expected to give speeches, answer questions at a press conference, and maybe even appear on a TV news report.

Rhonda, 29, an earnest woman with freckles and curly auburn hair that sweeps down over her forehead whenever she’s not wearing her fishing cap, tended to agree with her husband. Rhonda knew that her voice carried the twangy chords of the East Texas countryside where she was raised—a from-the-sticks drawl, she calls it. Yet, since she was about to begin the most momentous week of her life, she also knew that she should think about other things.

The Bass’n Gal Classic, held last fall on the 114,500-acre Sam Rayburn Reservoir in the Piney Woods of East Texas, is the tournament that just about every woman who picks up a bass rod and reel dreams about. At least that was how Rhonda saw it. There had been many times when Rhonda, after working down at the Norton Sand Company for $5 an hour weighing in trucks, wondered if she was not destined for something greater than her life in Malakoff (population: 2500). But it was not until a Texas woman named Sugar Ferris opened the male-dominated fishing world to women with the Bass’n Gal (short for “bassing gal”) circuit that Rhonda found her calling—bass fishing. “I knew it would end up to be something like that,” said her mother, Virginia Robertson. “When she was a little girl, she never cared for dolls. She stared at fishing stuff. So we got her a rod and reel when she was six years old. We once gave her a doll for Christmas. She went out and dragged it behind her bicycle on a string.”

Rhonda started fishing in the old water-filled gravel pits that her father managed. Now she had a chance to be the Bass’n Gal world champion. The first-place award was a new high-powered bass boat worth more than $18,000. Winning would mean endorsements. Her picture would appear in advertisements in fishing magazines. Her mother thought that if Rhonda won the classic, she could host her own fishing show on television, just like Jimmy Houston and all those other famous fishing show hosts they watched on Sunday afternoons. Come to think of it, winning might make the speech lessons more important.

Rhonda thought about the lessons for a long time; she never took her husband’s suggestions lightly. Bill had devoted weeks to helping her prepare for the tournament, even sharpening all the hooks on her artificial lures so that they would pierce the fishes’ mouths more easily. Finally, though deeply grateful for his advice, she had to go to him and say, “Bill, I can’t help it if I talk funny. I’ve got to worry about my fishing.”

Bill didn’t make a fuss about it; she was right. Her chances of getting close to the top were poor. This year was only her second on the tour, and she would be going up against women nearly twice her age, with twice the experience. Rhonda was trying to fight her way into an elite group of women bass anglers. Weeks before the tournament she had leafed nervously through Bass’n Gal magazine and stared at the pictures—the contestants were mostly working-class Southern women who had come from a life that demanded more grit than charm. Rhonda turned again and again to those pictures, sensing power in the faces coarsened by the weather. Those women’s lives had been transformed by their love of fishing. They were wives and mothers from traditional homes who were expected to remain wives and mothers, but they had become stars. People asked them for autographs. They wore satin jackets with their names stitched on the front pocket. They got free samples of new fishing lures from the big tackle companies.

There was Chris Houston, 38, an awesome figure in the sport, who had dominated women’s bass fishing for years, the way Martina Navratilova has controlled women’s tennis. Chris had grown up in rural Oklahoma, where she began fishing with her uncle when she was a little girl, married at 17, raised children, and on occasion went out to fish with her husband, Jimmy. He was so good that he won men’s bass tournaments, and he soon had a syndicated weekly fishing program that attracted fishermen the way a television preacher attracts fundamentalists. Chris had no idea that the way she threw her favorite lure, a spinnerbait, was practically unbeatable. She thought that for the rest of her life she would just be known as Mrs. Jimmy Houston. Then came Bass’n Gal—and after competing for six national championships and one world championship, Chris won a total of $124,000, more than twice the prize money of her nearest challenger. She became known as one of the best bass fishermen in the world.

Rhonda also stared at the picture of Linda England, 39, of Old Hickory, Tennessee, the mother of two who found herself taking her boat out on the lake alone, searching for some kind of peace that she did not get from cleaning house. “I would sit out there for hours,” she once explained, “just fishing, trying not to weep, and finally I realized that my extra fulfillment was going to come from bass fishing. It sounds odd, but it was the one thing holding me together.” She joined Bass’n Gal, started her own radio fishing show, and became the 1981 world champion. The success wrecked her marriage—she said that her relationship with her husband was never the same after she became famous—but never for a moment did Linda think about leaving the circuit.

Rhonda, sitting at home on her sofa, read all of the biographies. For hope, she read about the surprise winners, like Oklahoma’s Vojai Reed, the 1984 world champion, who had turned to bass fishing after her children had grown up. In 1983 a small-town Louisiana woman named Doris Canik came out of nowhere to win the Bass’n Gal Classic. She was as astounded as anyone else at what she had done. When she realized she was going to win, the large woman threw down her rod and began jumping up and down in her boat, nearly submerging it. Across the lake, people could hear her yelling, “I’ve never done anything before in my life! I’m with the big girls now!”

Even after reading about those unexpected winners, Rhonda wasn’t too sure about her own chances. She would put down the magazine, look at her husband, and ask, “What do you think?”

“Well, someone has to finish last,” Bill said, trying to be light.

Bill had begun to fall in love with Rhonda a little over two years before, at five-thirty one morning when he saw her on Cedar Creek Reservoir putting her fishing boat into the water without any help. He went over and asked if she needed any assistance. “I can do it myself,” she snapped, and Bill felt his head spinning with desire.

On their first date he took her fishing until dark. Then they ate pizza. “We figured the only reason Rhonda liked the boy was because he had a flashy fishing boat,” said her mother, who lived two miles by boat from her daughter across Cedar Creek Reservoir. Theirs was a fishing romance. In the first tournament that they fished together, a smaller competition on Lake Lewisville near Dallas that was open to both men and women, Bill pushed the boat through knee-deep mud so they could get to an old creek bed that he knew was filled with bass. He wouldn’t let Rhonda get out of the boat to help him. “That was real romantic to me,” Rhonda recalled. “Bill was taking me to his secret fishing hole. It turned out I caught enough bass to win the ladies’ division.”

In 1984, when Rhonda decided to pursue the Bass’n Gal circuit, an annual series of five tournaments held almost exclusively in the South, Bill started to act as a sort of a personal trainer. On their fishing trips he would offer encouragement while she stood up in the front of the boat for eight consecutive hours to develop the stamina in her legs necessary to fish a tournament. They worked to perfect her casting. Rhonda spent so much time on the boat that she gained ten pounds. During long afternoons, as the bass drifted through shallow coves in search of food, Rhonda and Bill drifted with them, their wrists expertly playing against their fishing rods, jerking the lures to life, putting on a show for the bass below.

In retrospect, though, the greatest sign of Bill’s dedication to his wife, and to the sport of bass fishing, was the vasectomy. Rhonda’s family was rather appalled, but that didn’t faze him in the least. Her family apparently didn’t understand the concentration required to catch bass. “I didn’t want anything to keep her from the lake,” Bill explains matter-of-factly. “This way, we can fish anytime we want to. Now think about it. Rhonda gets to keep practicing her fishing, without taking time off for a baby.”

Indeed, Rhonda had devoted her life to becoming the next Bass’n Gal champion. It was time to prove herself to the other women who had the same fervor and desire to win. “When I get finished,” Rhonda said as the tournament got under way, “all I want is for them to remember my name.”

The bass is the fish of Middle America. It has never had the following of those tweedy, long-winded Easterners who espouse the glorious nature of fly-fishing. “Good God,” says Robert Ferris, Sugar’s barrel-voiced husband, a hearty, backslapping man whose friendly handshake is almost bone-crushing. “I’ve seen oil paintings of those trout-fishing people. They look like goddam professors of English literature or something.”

Bass fishing—which generally takes place on man-made lakes, with state-of-the-art $18,000 powerboats, electronic fish-detection graphs that look more like submarine sonar systems, and bizarre artificial lures that bear little resemblance to any living thing that a bass actually eats—has never fit into the Waspish world of angling. Nor is the culture that surrounds bass fishing exactly what Izaak Walton had in mind when writing his literary treatise on the purity of fishing. Instead of bamboo rods, delicately tied dry flies, and a picnic basket by the side of a gin-clear trout stream, the bass fisherman’s world is one of big concrete boat ramps and cinder-block convenience stores decorated with plastic pennants where a fisherman can buy anything he’d ever need, from gimme caps to pocketknives to hot dog buns and beer. Within sight of noisy bridges spanning the lake, on the same water with skiers and horn-blowing houseboats, in little coves where people have dumped their garbage, or next to boat marinas where a film of engine oil floats over the surface, the bass fisherman looks for his wild fish and is able to touch that wildness with a simple fishing rod.

The peculiar difficulties of bass fishing—figuring out where the fish will be on a 100,000-acre lake, where they will go if the water temperature changes, what kind of lure they’ll strike, whether that lure should be thrown deep or pulled across the top of the water—soon lead to small tournaments on lakes where fishermen try to bring in the biggest stringer. In 1967 an Alabama man named Ray Scott began the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (BASS), the first organization to successfully promote professional bass tournaments nationwide. Today BASS says that there are nearly 20 million Americans who fish for bass. The total prize money on the BASS circuit is more than $1 million a year, and now there are several competing bass circuits for men, with similar amounts of prize money.

In his official rules Ray Scott added a line that in the early seventies began to bother Sugar Ferris, an affectionate, feisty woman who at the time was the outdoors recreation editor for the Lake Livingston Progress in East Texas. Scott stated that women could not compete in a BASS tournament, “in order to maintain our high standards of decency and to insure sexual privacy.”

“What that meant,” explains Sugar dryly, “was that a woman couldn’t be paired with a man because he’d get embarrassed when it came time for him to take a leak over the side of the boat.”

In 1972 with the help of her newspaper publisher, who bought a new boat to be given to the winner, Sugar organized the first National Fem Tournament for women, on Lake Livingston, just east of Huntsville. The tournament drew 96 women, “which astounded just about everyone,” recalls Harold Stone, a middle school principal from Coldspring, whose wife fished in that tournament and is still a regular on the Bass’n Gal circuit. “It was wild. All of us husbands were down at the dock the day of the tournament, double-checking the boats, yelling at our wives until we were white in the face, telling them not to crash our boats into the bank.”

Sugar kept the annual Fem tournament going through 1976, when she drew 118 anglers from eight states. “I knew I was onto something. But I didn’t know quite what,” she says. Then, on a sudden inspiration, she started Bass’n Gal, a national organization destined to change the shape of the bass fishing culture in America. Sugar started Bass’n Gal magazine, which had articles designed for women anglers (“Heads Up Gals—Those Batteries Could Mean Trouble”), and within a few months she had 500 members. By 1985 the ranks of Bass’n Gal had swelled to more than 13,000 women.

Sugar established Bass’n Gal headquarters in Arlington, and on her office wall she hung a largemouth bass painted a shocking pink—the official color of Bass’n Gal. Her husband, Robert, was named Bass’n Gal vice president and tournament director. Because of his background as a country music disc jockey, his wife gave him the extra responsibility of acting as the emcee at all the Bass’n Gal tournaments.

On the opening morning of the ninth annual Bass’n Gal Classic, the silver-tongued Robert Ferris stood in the parking lot among the contestants’ boats, put his coffee cup down on the curb, held a bullhorn to his mouth, and shattered the quiet with his call to arms: “Ladies, it’s time to stand by your boats. We’ll be loading up any moment now and heading down to the tournament waters. Golly, girls, I wish you the best of luck. I know those fish will be biting.”

In the pale, predawn light Rhonda Wilcox looked upon one of the most powerful images that a woman in tournament fishing could imagine. There in a long row, like an armada of small ships, were 33 fire-engine-red Ranger fishing boats with 150-horsepower Mercury XR2 engines hooked onto the back. Rhonda was trying not to look worried. But something, she knew, had gone wrong. She had fished the two previous practice days and had not caught any fish until the afternoon of the second day; those were too small to keep. It was absurd. She and Bill had spent eighteen days on Sam Rayburn Reservoir a few weeks before the tournament, trying to find the fish, and they had struck gold. Rhonda had caught so many big bass that she couldn’t help thinking about victory. She had even driven up to the Big Town mall in Dallas and spent $110—$60 more than she had planned—on a pink dress to wear to the closing banquet where, she dreamed, she would receive her first prize. Now the fish had left the spots she had so carefully chosen.

The boats, with each contestant in the driver’s seat, were put into the water, and the women waited quietly in the cove until Bob Ferris signaled the takeoff—the only part of the fishing tournament that was exciting to watch. For the rest of the day the anglers would be off in remote parts of the lake, their boats quietly idling in the water like grazing cattle. In the soft gray of first light, Bob Ferris’ most dramatic country-western voice boomed from the bullhorn, “Ladies, we’re one minute away from takeoff. Start your engines!”

The roar of the engines was deafening. The boats shuddered from the vibration, and the water turned into white foam. Frightened birds rose and wheeled behind a line of trees. The women pulled goggles down over their eyes and sat bolt upright behind their steering wheels, looking forward in a hard, militarylike way. Sixty seconds later the 1200-pound boats began to tear off one by one, like great hounds after a scent. Bows surged up out of the water, the wakes crashed together, and engine smoke hung over the lake.

Rhonda Wilcox, number 33, was in the last boat to leave the cove. As she made a mad dash to her fishing hole, a beaming Bill Wilcox stood on the bank and snapped photographs. Only much later in the afternoon would he discover that in his excitement he had forgotten to put film in the camera.

In the Bass’n Gal Classic each contestant is paired with a press observer, usually an outdoors writer from a newspaper. That arrangement allows the contestant full control of her boat and the tournament officials to have an outsider on the boat to determine that no cheating occurs. Each year Sugar Ferris reminds the contestants to look their best and to “act ladylike” in front of the press observers. She tells them to be considerate if a man asks to be taken over to the bank so he can use the bathroom, and she requests that her contestants not smoke cigarettes while photographers take pictures. The newspapermen, in turn, give Bass’n Gal a lot of coverage during the tournament, though many of the stories still tend to gush about these women who, by golly, can put on makeup and catch fish too! Old habits die hard. During the tournament one older writer from Wisconsin announced in the press room, “Women can’t stay out on the lake as long as men. They get sunburned, windburned, and blown about, you know. Some give up too easy.”

That kind of comment horrifies Sugar, who maintains that women are naturally better at fishing than men. She says that women always score better on tests for manual dexterity, eye-hand coordination, and digital sensitivity (meaning that their fingers wrapped around the fishing rod can “feel” a fish easier than can a man’s). With a smug look on her face, she even produces a vague report of a study conducted in British Columbia in 1951 that asserts that the bodies of men, not women, emit a certain kind of amino acid that repels fish. “God meant for us to fish,” says Sugar. “That’s all there is to it.”

Of course, there is the possibility God forgot to tell some men that—especially when women began to enter all-male tournaments. In 1976 Sugar entered a bass tournament in Arkansas where the organizers happened to leave out the male-only rule. There were 237 contestants; she was the only woman. “When they called out the pairings, this old fisherman from Missouri heard he was paired with someone named ‘Sugar.’ He hadn’t figured out yet that I was a woman. ‘Where’s Sugar Ferris?’ he called out. I came up and tapped him on the shoulder. He looked at me for a moment as if he had seen a ghost. I swear to God, the man walked right over to the doorway, bent at the waist, and threw up,” Sugar recalls.

As their skills and confidence improved, women had to deal with an even stickier situation—their husbands. “It’s one thing for a woman to start working in the same profession as a man,” says Bass’n Gal contestant Kathy Magers, “but it’s a whole different story when you begin to intrude on his passion.”

Kathy, 40, a radiant woman from the little East Texas town of Frankston, knows all about the hazards of a passion for fishing. A part-time hairdresser for 23 years and a mother of two married to a former high school football star, she began fishing with her husband, Chuck, when she was 29. “Honestly, I wondered if our marriage could survive it,” she recalls.

“Look,” says Chuck, a husky man who is director of sales for a food distributor, “I fell in love with my wife because she had a lot of inner strength. You sort of like that in a woman. But I’ll be damned if that works on a boat. Every time we went out fishing, I’d find myself stomping off to the back of the boat, smoking a cigarette, pissed off because she wanted to fish in a spot that I didn’t want to. Really, that’s a big deal for a fisherman.”

“If you want to know the whole truth,” says Odell Haire, 62, the gruff-looking husband of North Carolina’s great angler, Betty Haire, “a lot of men are jealous of those of us who have made our wives our fishing buddies. Now, the first woman I married had, as far as I could tell, just two ambitions in life—to stop me from hunting and to stop me from fishing. I said, ‘to hell with that. The next wife is going to like what I do,’ and that’s what I found in ol’ Betty. When she finally went fishing with me, she took to the boat and water like a duck.”

For nearly eight hours, the Bass’n Gal contestants stayed on the lake, casting and reeling, casting and reeling. Bass fishing in real life is not like that on television fishing shows, where the host will catch thirty fish in thirty minutes and never stop talking. It is more like an extended game of solitaire: each competitor, standing on an eighteen-foot-long boat and surrounded by graphs and meters, throws out an array of absurdly named lures (like the Bomber Bushwacker or Whopper Stopper Dirty Bird) and hopes for that one jubilant moment when the water suddenly boils, the fishing rod warps, and a wide-eyed, bronze bass bursts through the surface.

Sometimes a bass is ridiculously easy to catch, but there are times when it seems impossible. The time of the year when the Classic is held—late autumn—tests the patience of even the best fishermen because as the days shorten and winter approaches, the bass become more unpredictable. Some begin to move into deeper water as the temperature falls, others continue to school among shallow creek channels. Some strike any bait, others simply hang in the water, sluggish as a man with middle-age spread. The bait that bass on the left side of a cove strike might not be what the bass on the right side of the cove want.

On the first day of the tournament, Chris Houston chose to fish beside a point that jutted into the main body of the lake. She had caught several fish there in practice and sensed that they would still be around. Chris develops a detailed game plan before a tournament, but what makes her a star is that at times she will abandon her plan and fish by instinct, going into little coves or flooded timber areas she has never fished. “I sometimes get a strange feeling that fish are around. I don’t know where it comes from—probably from fishing for so many years, I guess—but I know it’s something I cannot ignore,” she explains. Chris had found her area for the Bass’n Gal Classic on an impulse during the last day of practice. She had spent all morning working unsuccessfully in another bay and decided to leave. As she was gunning down the lake at nearly sixty miles per hour, she looked off to the left, as if for no reason, and slowed down. She moved toward the bank, got out her rod, and caught a two-pound bass on her first cast.

Burma Thomas, the 1982 world champion who over the years has proved to be Chris’s best opponent, decided to try a small area in a basin just up the lake from Chris. Burma, 46, grew up on a farm, one of eleven children, dreaming that one day she would become a country music star “because that’s about the only thing country girls had to dream about.” Then in 1968, the first time she ever went fishing, she caught a four-pound bass; she has dreamed about little else since.

Burma had been on a roll this season, fishing well in most of the tournaments. She was named Angler of the Year in a women’s bass fishing circuit begun in Florida in 1985. But what Burma wanted to do was something Chris hadn’t yet done—win a second Bass’n Gal world championship. Burma had spent most of the autumn trying to figure out how to beat Chris, coming to the Sam Rayburn Reservoir as far back as September to look for the right place to fish. With her thick blond hair sticking out of the hole in the back of her fishing cap, Burma worked one small area, about fifty yards long, where vegetation was growing under the water. She was gambling everything on that one spot. As she cast, the boat ghosted along under the low, gentle hum of the trolling motor.

The most noise on the lake might have come from the fiery engine of boat number 33. Rhonda Wilcox was not like Burma Thomas, who would sit in one place all day and wait. First, waiting requires an enormous amount of patience, which Rhonda still was young to have developed; and second, Rhonda wasn’t sure she even knew where a good fishing hole was. Her plan to get among the leaders included thundering around the lake, trying different spots until she hit something.

She zipped across the lake into her first spot, caught a few fish, and by ten-thirty was roaring back across the lake to try another place. At times Jim Foster, a Texas outdoors writer who was Rhonda’s press observer for Friday, found himself watching her in disbelief. “Rhonda,” he finally said, “don’t you think you ought to slow down a little bit?”

She didn’t. She continued to fish at her relentless pace, refusing to let her hopes die, her normally pleasant face frozen in a grimace. At the Bass’n Gal tournament contestants may bring in five of the biggest bass they catch during the day, the only stipulation being that each fish must measure at least twelve inches long. By eleven o’clock, an hour and a half before she was to go back to the dock, Rhonda caught her fifth keeper bass. “Oh, mercy,” she said to herself. “At least I won’t be embarrassed.” She relaxed enough to talk to her press observer about her gun collection.

Little did Rhonda know how well she had done. By the end of the first day, eight contestants came back without a keeper fish, and fourteen returned with a poor catch of less than five pounds. Rhonda’s bass totaled a little over eight pounds. “You’re in the top four,” her husband told her. Rhonda couldn’t believe it. The only women ahead of her were Chris Houston and Burma Thomas, who each brought in ten-pound catches, and a 46-year-old dark horse named Pat Antley, a thin, rawboned woman who lived on a Christmas tree farm outside of West Monroe, Louisiana, that she operated with her husband.

Pat taught girls’ physical education at a small-town Louisiana high school for twenty years before retiring two years ago to fish Bass’n Gal full-time. She nearly ran away with the tournament on the first day, coming in with five fish weighing fifteen pounds twelve ounces. She had slept only an hour and a half the night before and felt “like a sick dog” the morning of the tournament. Fishing in a shallow area of the lake filled with lily pads, however, she caught her first fish within ten minutes. She knew then that she was onto what longtime fishermen call a honey hole. After Pat caught a huge, four-pound bass she sat down in the boat, hands trembling, and said to her press observer, “I can’t handle this. I’ve got to have a cigarette.” After her fifth bass she sipped coffee from a thermos and almost wept.

“My God,” Pat said back on shore, trying to explain her emotion. “When I quit teaching I was making only eighteen thousand five hundred dollars a year, and that was after twenty long years. Now I’ve got a chance to make all that in one weekend. I’m just an old schoolteacher. This isn’t supposed to happen to me.”

At the contestants’ meeting that night, the women talked to one another about the same things fishermen have discussed for centuries—what the fish were doing, what kind of lure they were striking, what the weather was like. Pat Antley, her dark eyes like black circles, looked off toward the wall as if still in shock. Then Sugar called the leaders forward to talk about their day on the lake. Rhonda’s chance had come to prove that she didn’t need those speech lessons after all. When it was her turn, Rhonda, filled with pride, stood before the crowd and bent toward the microphone with a big smile.

“Girls, what can I say?” Rhonda asked, looking out on the women she had admired for so long. “It was just dang pretty out there on the lake, dang pretty, and I hope it’s that way tomorrow.” She paused, glanced around, then seemed to remember what people were supposed to do at press conferences. She leaned back toward the microphone. “Any questions?”

The only real question, as the women in their boats headed out onto the lake for the final day of the tournament, was whether anyone could catch Pat Antley. No one knew where she was fishing or what kind of bait she was using, and Pat certainly wasn’t going to say. Contestants have an unwritten code of honor that dictates they will not fish in a spot someone has already staked out, but that code does not keep them from trying to find out what everyone else is doing.

Another factor arose as the day began—the weather. The wind had come up, not hard, but enough to send little ripples through the water and keep the anglers from seeing what was directly below them. And that’s why, when Pat Antley got to her honey hole, she thought she might be in trouble. The day before, she had been able to see openings in the vegetation below the surface where she could throw her lure and wait for the bass. Now, as the color was still coming to the sky, Pat was not sure if she would be able to run her lure over the right places in the murky water.

Nevertheless, she knew she needed only two or three good fish to win the classic, and the day before she had seen several large bass that she had not caught. She decided to stay. Alert as a deer, her chin thrust forward defiantly, she started to fish. The water lapping against the boat had a melancholy effect, repeating itself a thousand times. Pat had made a choice that would change the course of the tournament.

Chris Houston and Burma Thomas returned to their separate spots as well. Neither thought that she would be able to catch Pat Antley, but Chris had been in a similar position many times. She tied on her reliable spinnerbait. She seemed oblivious to the drama unfolding in the waters below as she cast with uncommon elegance—beginning with a slow back swing over her shoulder, then the release, sending the lure precisely to its target, landing it with a tiny, delicate splash. Her boat moved stealthily along the bank.

Burma, meanwhile, bent a little toward the water like a retriever nosing through leaves out in the woods. Her trolling motor was on high as she wove through the grass in the fifteen-foot-deep water. She too would have trouble keeping control of her chartreuse lure in the choppy water. With only an occasional wandering thought about how Pat and Chris were doing, Burma concentrated on her casting.

The only time Burma might have been distracted was when Rhonda Wilcox, her face red-tinged under her fishing cap, came tearing into the cove, staying all of fifteen minutes. Rhonda had started on the west side of the lake, where she worked an area for an hour, then frantically sped across the lake near Burma’s area. When she didn’t get a quick bite there, she was off again, leaving a highway of white water in her wake, running up-lake to fish another one of her spots. She fished for thirty minutes there, didn’t get a strike, and slammed the engine into gear to go somewhere else. Her boat surged out of the water like Moby Dick about to knock the hell out of the Pequod. Rhonda, trying not to panic, was spending nearly as much time rushing around the lake as she was spending fishing.

By then it was ten-thirty, and she didn’t have a fish. She was far up the lake, in spots she had rarely fished. Near a marina, her fourth stop of the day, she finally caught two keeper fish. Then, growing impatient, she moved again, farther north, right off a river channel. There, at about twelve-thirty, her heart began to quicken. Rhonda was throwing her white lure toward some moss submerged in about eight feet of water. She looked over the boat as if she were looking over a cliff. “I had to catch something,” she said later, “and I had to catch it fast.” The sunlight went in and out from behind the clouds. A clump of willow trees half-drowned in the water nearby looked like old gray ghosts. The trolling motor never changed its pitch. But as the lure was reeled in, something large, something invisible tugged on the line. Rhonda felt it. She pulled back a little, then she pulled back again hard.

A bass shot up into the air, bucking away like a bull, trying to leap back as it was pulled inexorably forward. Rhonda was thrown into a momentary dislocation; afterward she would say she had no idea how big the bass was. Instinctively, she lowered her rod tip and kept reeling. The bass gave one more malicious lunge, then gave up. Only after it had been netted did Rhonda realize she had cranked in a five-pound ten-ounce bass. A little bit later, in yet another spot, she caught a three-pound bass. Her fortunes had changed.

Indeed, the fortunes of the entire tournament were about to change. One hour after Rhonda got her big fish, Pat Antley was getting ready to go after hers. So far, Pat had caught only two fish, totaling two pounds thirteen ounces. She knew she had to have one big bass to stay on top. With each moment the tension and despair built. Pat, poised alone in the pine shadows amid the moldering sweetness of the shallow water, concentrated on keeping a steady line.

Expert anglers talk of how they can sense that a fish is about to strike their lure, just as a golfer knows the ball is going to drop the moment he makes a putt. That’s why, as the bass hit, Pat was already pulling back with her rod. The fish immediately heaved itself out of the water. Pat stared at it. The bass was massive. It was exactly what she had been dreaming about. It was the kind of fish that would clinch the Bass’n Gal championship. Up and up the bass rose, its bronze-colored armor flashing. Then its head jerked violently as it fell back to the water. And all of a sudden it rose again, trying to shake the lure out of its mouth.

In that split second Pat realized with horror that her line was too slack. She reeled as fast as she could, but there was no time. Quick as lightning, the confrontation was over. The fish had dislodged the hook and was gone. Pat stared at the empty lure. She knew nothing was there, but she kept looking at it anyway.

After a few seconds, she turned to her press observer. “There just went my eighteen thousand dollars.” She sat down for a few minutes, trying to compose herself.

The afternoon wore on, and Pat didn’t get another fish. It was time to come in to see who had beaten her.

On the bank, in front of a large scoreboard where the name of each contestant was listed, Robert Ferris stood on a stage and, to fill time, tried to regale the audience of 150 people with just about anything that came to his mind. The contestants were down at the ramp, loading their boats onto trailers. Then, seated in their boats, like beauty queens on parade in convertibles, they would be driven in front of the stage, where the fish would be weighed and the winner announced.

One by one, the contestants were brought forward. Some of them waved at the crowd. Solemn little towheaded boys, women with the kind of beauty-parlor hair that hairpins get lost in, and relatives with anxious, stern expressions all watched as the fish were pulled from the boats. Whenever a big one was held up, the people reacted like a primitive tribe gasping at the sight of an eclipse.

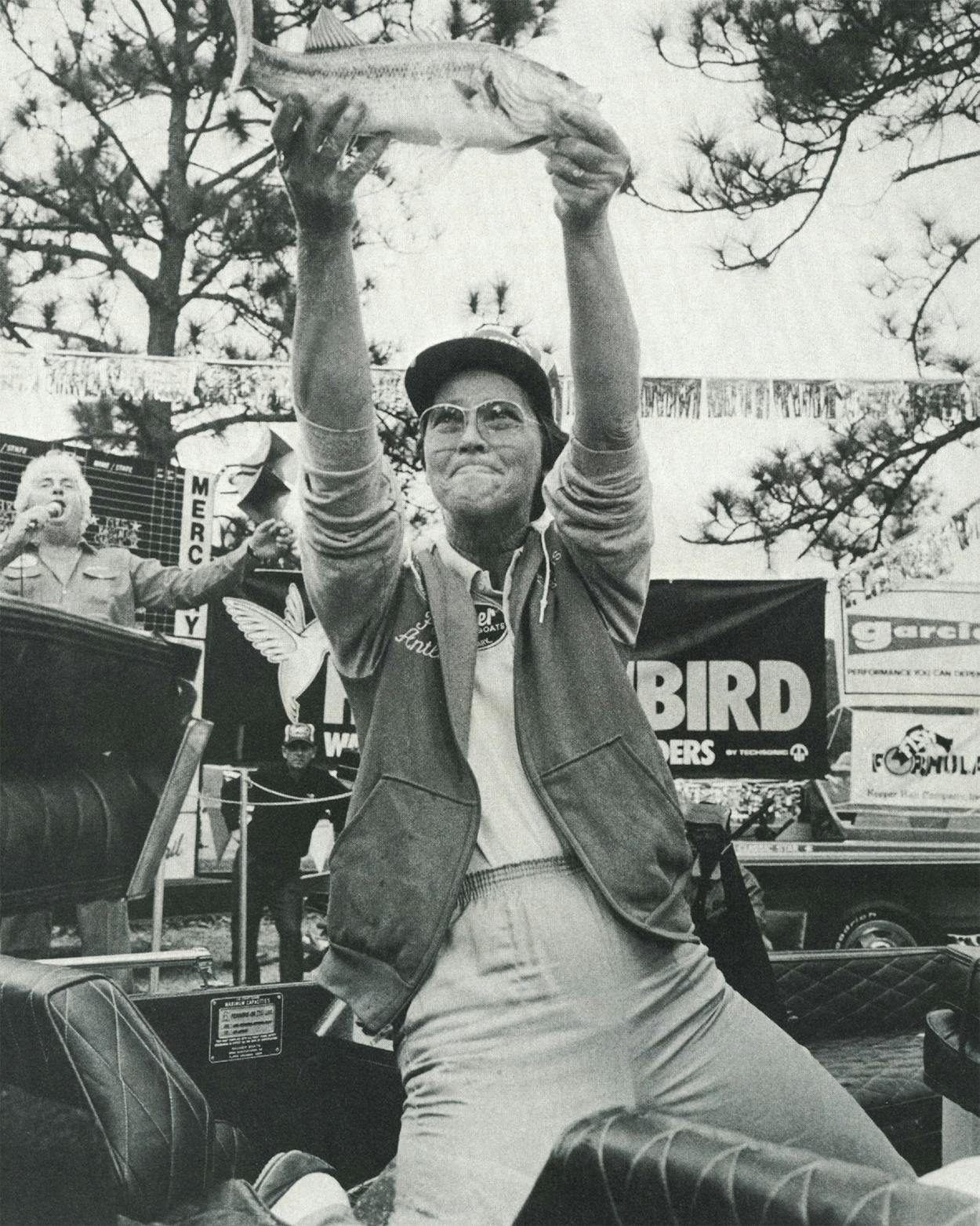

Waiting in line for her turn, Rhonda Wilcox looked almost physically ill. She held up all her fish. The five-pound ten-ounce bass, the largest caught in the tournament, was greeted with a roar. In the sunshine, the water dripping off the bass sparkled like jewels. The fish was thrashing in her grasp. Robert Ferris announced that Rhonda’s total catch of eighteen pounds thirteen ounces had put her in the lead, and Rhonda, nearly staggering, turned to the crowd and acknowledged the applause in such a dazed, self-deprecating way, her hand making a shadowy gesture of wonder, that one could not help but be touched. Sugar Ferris, down at the scorers’ table, glanced up and shook her head. “Look at her,” said Sugar in a motherly way. “That’s the new generation of bass women.”

Then it was time for Pat Antley to show her catch. When she held up her two small fish, the audience groaned. Tears were in her eyes. She went over and stood beside some old friends who had driven from Louisiana to see her win. When she quietly told them about the missed fish, one old man in overalls looked into the bottom of the tobacco juice cup he held in one hand. “Doggone, Pat,” he murmured, “I wish there was something I could say.” Others gathered around to offer condolences. But Pat, her flat, nasal voice punctuated by a weary sigh, explained the pain of fishing with the well-known credo. “Hey,” she said, “that’s bass fishing.”

Rhonda’s excitement grew as Chris Houston arrived with only four fish, weighing five pounds fourteen ounces. The star flashed a smile at the crowd, her bearing still that of a champion, but she knew that this was an uncharacteristic tournament for her. She had lost a four-pound fish on the first day and then a three-and-a-half pounder on the final day. “I lost this tournament all on my own,” she later said. “I just plain beat myself.” Her total catch left her more than two pounds behind Rhonda. The crowd began to murmur. They knew an upset was in the making.

The outcome of the ninth annual Bass’n Gal Classic lay in the catch of Burma Thomas, the last contestant to come to the stage. She rode up wearing little diamond earrings and new tennis shoes. Her ponytail was freshly brushed. When she pulled out her first fish, the fishing paparazzi pushed against the boat, snapping picture after picture. It looked like the academy awards. Burma Thomas, her teeth flashing, her prize fish held high in the air, posed like the glamorous country music star she had always thought she would be.

Burma handled her last fish as carefully as if it were a piece of family silver. Robert Ferris was shouting into the microphone, “This is what we call suspense. Burma Thomas has four fish, and they have to weigh more than seven pounds eight ounces to give her the championship! Hold on to your hats. It’s coming down to this!”

Ferris put all of the fish on the scale. Burma let out a rebel yell and bounced up and down. The fish weighed nine pounds eight ounces. Burma had become the champion for the second time. “It’s Burning Burma Thomas!” Ferris yelled into the microphone. The photographers gathered around to take more pictures of her—holding up a lure, holding up fishing line, standing beside her new boat, and standing next to an outboard motor.

Rhonda wore her pink dress to the banquet that night. While a bubbling Sugar introduced nearly everyone there, including a man she called the father of the Mercury XR2 engine, Rhonda sat beside her husband. “I’ll be back,” she said, her voice reverberating with the elation that comes from hope. “I’m going to fish all winter, I’m going to study fish, I’m going to eat and breathe fish, and I’m going to be back to win this darn thing.” A few of the men, won over during the tournament by her charm and innocence, came up and hugged her.

For many of the women it was the last time they would fish until spring. Already the anglers were talking about a cold front. Outside, as darkness spread over the hills, veiling the silent pines, a chilly wind began to scamper across the lake, making a hollow sound as it drove up into the trees. Car headlights disappeared over a ridge. The songs of the birds were still. In a slow, subtle cadence, another of nature’s seasons was beginning to change.

Pat Antley left early to get home to Louisiana so she could open the Christmas tree farm the next morning; 1800 trees had to be sold for the Christmas season. Her mind, though, was on the next spring, when she planned to return to Sam Rayburn Reservoir to move out over the same waters and to search out that same honey hole and find the one that got away. “You can’t forget him,” she explained, “not for the rest of your life.”

And so she would throw out her line, standing in her boat with an aching desire that only one fish could satisfy. Though she would try again, and then again, Pat Antley knew there was little chance she would ever see that bass. It was as if the bass had paused in its journey for one solitary moment and then had disappeared, to retreat always before her down a dark and watery path.

Skip Hollandsworth is a writer who lives in Dallas.

- More About:

- Hunting & Fishing

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fishing

- East Texas