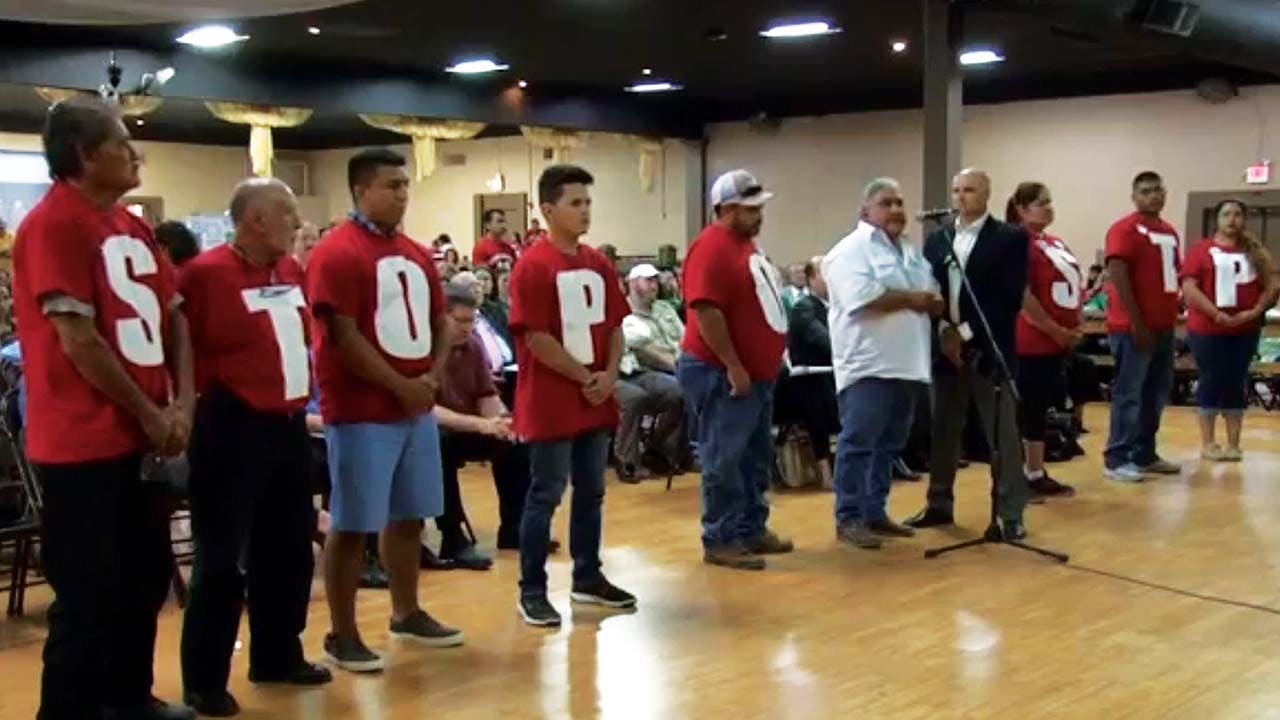

Much of the crowd at Laredo’s Casa Blanca Event Center on the night of August 11 was color-coded. Those who supported the construction of the Pescadito Environmental Resource Center (PERC) wore green shirts emblazoned with recycling symbols. Many of those who opposed the construction of the euphemistically named landfill wore red shirts that emphasized community solidarity. Together, they numbered in the hundreds, and passions were high enough that a representative of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality struggled to impose order during the four-and-a-half-hour meeting.

To the right of the lectern sat Carlos “C. Y.” Benavides III, the head of a branch of one of Laredo’s oldest and most powerful clans, who has staked his name on plans to build this landfill on the family’s Yugo Ranch, some twenty miles east of the city. Nearby sat a leader of the opposition to the dump, Anna Galo, who also happens to be C.Y.’s estranged first cousin. Throughout the night, C.Y. perched on the edge of his chair, answering questions and parrying concerns, while Anna stayed off to the side, in silence.

The meeting was the second time the TCEQ had taken public comment on the landfill proposal. The first meeting, in 2013, had attracted a smaller crowd, and for the past few years C.Y.’s plans seemed to be moving forward. But this year the TCEQ reopened the permitting process to correct a technical issue with the original proposal, and opponents saw an opening.

Sharon Jordan, whose family ranch is adjacent to the proposed dump, stood at the microphone at the front of the room and called the project “an abomination against God and man.” Her sister-in-law Rosemary Jordan Contreras, whose land sits about a mile from the site, addressed C.Y. directly, saying that she was “appalled at the total lack of respect and consideration for the lifelong bond nurtured between landowners for over a century.” She then struck an even more personal note: “I knew your grandfather and your father before you ever did, and I know that they would not approve of what you are doing.” C.Y., for his part, said that his project offered “an alternative for all humans,” a solution to global environmental issues that would extend “far beyond our lifetimes into our grandchildren’s lifetimes.”

The Pescadito Environmental Resource Center’s name makes it sound like a marine sanctuary, but it would be what is colloquially referred to as a “megadump.” The Kansas City Southern Railway, which controls the rail bridge across the Rio Grande and extends deep into Mexico, runs next to the Yugo Ranch, low, flat scrubland that C. Y.’s ancestors have tended for generations. It’s C. Y.’s aspiration that one day, pending a permit from the TCEQ, trains full of undesirable material—including municipal waste, industrial waste, fracking waste, and coal ash—will come to his ranch and leave their trash behind. C.Y., who both admirers and opponents say talks in superlatives, maintains that the dump will be one of the most environmentally

friendly facilities of its kind in the world. Many of his neighbors—relatives, fellow landowners, and the several hundred residents of Ranchitos Las Lomas, a colonia several miles from the proposed site—are less optimistic.

As the TCEQ moves closer to finalizing C.Y.’s permit, the opposition is heating up. Citizens Against the Laredo Landfill (CALL), a group that receives much of its funding from C. Y.’s uncle (and Anna’s father) Arturo Benavides Sr., is running frightening TV ads. C. Y. has matched the effort; he says he has spent more than $5 million in support of his cause.

This public family feud lends itself to sensationalism, and it’s been a primary focus of the Laredo media (sometimes to the irritation of the dump’s other opponents). CALL paints C.Y. as a scoundrel and a liar, a “professional gambler” and an inveterate failure whose character should disqualify him from being entrusted with just about anything. C. Y. portrays himself as the victim of a conspiracy, in a community that treats people with bold aspirations like “crabs in a bucket.”

In Laredo, as everywhere, waste is created collectively, and safely disposing of it is a moral imperative. But the costs of waste management are shared unequally. The PERC’s relative proximity to Ranchitos Las Lomas has sparked accusations of environmental racism; dumps often end up near those with the least political and economic power. But within the Benavides family, the debate over the dump hinges on other profound questions: What is it we owe to those we inherit from? And what do we owe to our descendants?

For about eleven months in 1840, when Laredo was the de facto capital of the Mexican secession movement of the Republic of the Rio Grande, the city was at the center of something. For the rest of its history, it has been an outpost in the liminal space of one or another polity: a frontier city between New Spain and its unsettled northern territory, a stop along a cotton-smuggling route between the Confederate States of America and Mexico, an inland port for beneficiaries of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Laredo’s economy is premised on the passage of things through the city: raw materials, manufactured goods, people, money, drugs. Waste, whether from Mexico or Houston, would be an aberration, in that it’s a by-product of trade that would come and stay there forever.

For a place so dependent on transience, the order of things is determined to an unusual degree by the influence of old families, of which the Benavides clan, which claims lineage to Don Tomás Sánchez ,the founder of Laredo, is one. Downtown Laredo’s Museum of the Republic of the Rio Grande was the home of Carmen Benavides in the 1830s and now functions in part as a family archive. When the American Army came in 1848, Basilio Benavides helped deliver a petition to allow Laredo to remain in Mexico. During the Civil War, Colonel Santos Benavides, the highest-ranking Tejano in the Confederate Army, played a crucial role in keeping the cross-border cotton trade active, propping up the Confederate economy. The museum’s displays tout Refugio Benavides’s coal-mining operation, which fed the railroads that started to come through in the 1880s.

In the twentieth century, the family’s extensive land holdings enabled them to take maximal advantage of the oil and gas boom, and the Benavideses have been major figures in town ever since. C. Y. prides himself on his support for environmental causes and philanthropy; he’s a major booster of the Boys and Girls Clubs of Laredo. Anna’s branch of the family holds political sway; her husband, John, serves as a county commissioner, she’s close friends with state senator Judith Zaffirini, and the current mayor used to be her lawyer. Governor Greg Abbott has placed her on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission and the Texas Historical Commission.

For years the Benavides family passed power from one generation to the next in the manner of medieval nobles: upon a patriarch’s death, his holdings would be subdivided among male heirs. “Until my generation, they never gave land to girls,” C. Y. said. “It was all guys, and they would kind of keep it together [under one family name].” When his grandfather passed away, he said, some of the land went to Anna’s branch of the family. Seeking to prevent the further fracturing of assets, C. Y. persuaded some of his relatives to join a holding company for their land, the Rancho Viejo Cattle Company. That’s the group now backing the landfill proposal. Anna and her father and brother declined to join; they have their own holding company, ANB Cattle Company.

Normally in these sorts of stories, the person looking to build a controversial project doesn’t want to talk and the opposition does. In this case, it’s something close to the opposite. Anna agreed to a brief interview on a conference call with her top adviser on the project, the veteran Austin lobbyist Ray Sullivan, and remained guarded throughout. C. Y., by contrast, will talk endlessly to anyone who will listen.

Over a frozen mangonada at a shaved-ice store in a Laredo strip mall, he laid out his argument. In 1978, he said, when he was a teenager helping out at the 12,000-acre Yugo Ranch, he asked a visiting geologist about a great flat expanse with white patches in a corner of the property. It seemed perfect for drilling. But he was told there was no gas there; it was the top of a salt dome. “The highest and best use for this place is a landfill,” C. Y. said he was told by the geologist, because the clay formation at the site would let very little water through.

C. Y. eventually went off to college. During his senior year at Sul Ross State University, his grandfather got sick, and C. Y. dropped out to manage the family properties. “It was my dream job,” he said. “I had two thousand dollars a month, and I had a truck. What else did I need in life?” But in the following years, reality set in. “Well, this can’t be everything in life, right? There’s got to be something else.”

So he decided to make his name, with the family purse at his disposal. “I’ve always been an idea guy. You’ve heard from my cousin that I have ‘crazy ideas.’ My crazy ideas come to life.” There was Trophy, a magazine for trophy hunters, which eventually folded; an online gambling concern, Deliverance Poker, which collapsed after a star player (“The Grinder”) defected to a rival; and, most spectacularly, a $43 million plan to build the tallest structure in Laredo, a sixteen-story luxury apartment building called the Emerald Tower, which never materialized.

And then there was the Camino Colombia, C.Y.’s biggest project, a $100 million, privately owned toll road that would connect a border bridge to a stretch of I-35 north of Laredo, which would have allowed commercial trucks from Monterrey to bypass the border cities and proceed directly to San Antonio. The road’s opponents, which included the Laredo National Bank, charged C.Y. with putting his own financial future ahead of the well-being of the community. They waged a years-long fight, with the help of state senator Zaffirini, to delay the road’s construction while another group built the World Trade International Bridge, which would be the third bridge carrying commercial traffic between Mexico and Laredo. By alleviating the congestion that plagued drivers on the two other bridges, the new one would obviate much of the need for Camino Colombia and secure the city’s hold on commercial truck traffic.

They succeeded. Camino Colombia opened in 2000 and was foreclosed on three years later after less-than-expected truck traffic brought in less-than-expected revenue. (It is now operated by TxDOT.) But the road’s saga incurred an additional casualty. Even before Camino Colombia failed, Anna’s family, which had invested in the road, fell out with C.Y. over what they called his dishonest business practices. A lawsuit, filed in 1995, thus began a 21-year feud between the two branches of the family.

Despite these difficulties, C.Y. sees even his less-successful ventures as victories of a sort. Camino Colombia, he says, was the first privately built road of its type in the state. “We wrote the history book,” he said. “How many people can say that? That they did anything that affected history? That’s an incredible thing.” He frames the road’s foreclosure as a kind of wealth redistribution: he took money from well-heeled investors and brought infrastructure to Laredo.

C. Y. is a born showman, comfortable in the role of the boastful patriarch. In 2006 he ran for Webb County judge; an article in the Texas Observer at the time notes that in order to “raise his profile,” he hosted an auto show, held an art exhibit with some of his original pieces, and organized a concert featuring a former member of Foreigner. It also mentions that he took a break from campaigning to “chase a longtime dream of hunting Marco Polo sheep in the subzero climes of Tajikistan.”

Anna’s representatives repeatedly point me to another section of the Observer article: C. Y. was taken into police custody three times over allegations of domestic violence but never charged. (C. Y. chose not to discuss the matter with Texas Monthly, though his ex-wife, who was the alleged victim of the violence, sent a note absolving him of any wrongdoing.)

The legal battle over C.Y.’s latest “crazy idea” is complicated, but the arguments for and against the landfill can be roughly summarized. C.Y. says that his site is uniquely situated to store waste safely because of its geologic features and relative distance from town. He wants the dump, he says, because finding ways to securely dispose of waste is an urgent mission. “There are islands of trash in the ocean that are bigger than the state of Texas,” he says. “It’s not something that people like to think about.” He believes the landfill will help secure a better financial footing for his family—C.Y. characterizes the family as “land rich”—but he claims it will be a boon to the community too, bringing new industrial activity. What’s more, he asserts, Laredo’s existing city landfill is almost full (a point that many contest), and more people live near it than near C.Y.’s property.

Opponents of the PERC don’t take C.Y.’s frequent assurances of competence and safety seriously. His relatives are particularly harsh in their assessment. During our phone call, Anna made note of C.Y.’s “high-profile business and political failures,” adding that “every project that he gets involved in is always the ‘best in the world,’ the ‘best in the nation.’ You’ll always hear him say that.” And unlike Camino Colombia, a landfill would put more than money at risk. “This is the worst of all his proposed projects. And the scariest,” she said. Asked if C.Y. is capable of managing a project like this, Anna is unequivocal: “Absolutely not.”

C.Y. resents his cousin’s involvement in mobilizing opposition to his dump. He describes Anna and state senator Zaffirini—who has been providing tacit support to PERC’s opponents—as members of a cabal, working against his interests out of spite and jealousy. He points repeatedly to a letter he received in 2012 from ANB’s law firm offering to drop the challenge to the TCEQ permit application in exchange for a cut of the royalties from the dump. C.Y. says it shows Anna’s motives are impure. Anna says the settlement was offered without her permission or knowledge. (The law firm did not respond to requests for comment.)

But there are many objections to the PERC that have nothing to do with family politics. The dump would be situated near San Juanito Creek, which, during heavy rains, rises and eventually flushes into the Rio Grande, already one of the continent’s most polluted rivers. C.Y. pledges to raise the dump above the hundred-year floodplain, but Laredo receives torrential rainfall, and many parts of Texas have been seeing hundred-year floods at intervals much shorter than a hundred years. “Any rancher will tell you: you can’t control water like that,” says Pamela Jordan, a member of the neighboring Jordan family who is one of CALL’s leaders. The area is also exceptionally windy, and neighbors fear the dissemination of waste products like coal ash, which contains abundant heavy metals.

Fire, too, is a concern. Landfill fires can be serious, and natural gas lines crisscross the area. Though C.Y.’s TCEQ application promises that his site will remain in “a constant state of firefighting readiness,” there are no firefighting facilities of note nearby.

Many Laredoans also hate the idea of becoming a repository for foreign trash. The PERC would take waste not only from the region but also from a zone that stretches from Arizona to Alabama and a good portion of the Mexican maquiladora system. It’s an insult to the community, they say, to turn the city into a dumpster for others.

Several miles to the north of the dump site stands the colonia Ranchitos Las Lomas, which is full of low-slung, temporary-looking housing whose residents have sometimes done work for the Benavides family. Alejandro Obregón, for instance, worked on C. Y.’s 2006 campaign; his house sits in the corner of Ranchitos Las Lomas that is closest to the proposed dump site. He has threatened a hunger strike if the permit moves forward.

Beyond the concerns that can be easily quantified, the dump’s neighbors say C.Y.’s proposal is a violation of the intergenerational compact Laredo landowners have with one another. “No rancher would put a dump on their ranch,” says Jordan. The Jordans have owned their land for more than a century, and members of the family are buried there. “My father worked all his life to build a home out here. He says this land killed his mother, and now it’s going to kill him. He’s so depressed. He doesn’t even want to get up anymore.”

Anna feels similarly. “My grandfather spent every single day of his life working that ranch and taking care of that ranch,” she says. “He wouldn’t even let us throw away a piece of gum on the property. It actually sickens me that his grandson, whom he loved so much, would turn his ranch into a massive toxic dump.”

C.Y. disagrees. His grandfather was a businessman, he notes. That’s why the family has this land in the first place. His neighbors can talk about the beauty of ranching all they want, but the fortunes of the area’s landowners are built on the dirty business of oil and gas extraction, not ecotourism. If someone had approached his grandfather with an opportunity like this, he thinks he knows what his grandfather’s answer would have been.

One August afternoon, C. Y. offers to take me on a helicopter tour of Laredo. “The land doesn’t lie,” he says. Heading east from Laredo above Texas Highway 359, you can see the past, present, and future of the city’s waste management. The city landfill is a mess—two-hundred-foot-tall ziggurats of trash imperfectly covered by dirt—and even from high above, the stench is overpowering. Days before, the city saw heavy rain. In one section of the lot, running water, sickly green in color, escapes the site through a fence, spilling into a drainage ditch that meanders past many new homes and a high school.

C. Y. describes this as the very opposite of the sort of dump he wants to create. The city landfill has been the subject of numerous complaints from the TCEQ over the years, and it just got a permit to take even more trash. He talks about the possibility of moving waste from here to the PERC, allowing a more permanent fix. A few miles east is the Ponderosa Regional Landfill, a privately run facility that opened in 2013 to take municipal waste and recently received permits to accept industrial waste too.

From the air, C. Y. sees mostly hypocrisy. The groups opposing his plan to accept industrial waste didn’t give Ponderosa the same scrutiny. People don’t seem to care that the city landfill, which also accepts waste from Mexico, is close to many homes. And the Mexican officials who fear contamination of the Rio Grande by the PERC have no right to complain, he says, since they dump raw sewage into the river.

When we fly over the colonias, he points out the piles of trash many residents have in their own yards and the little dumps that frequent the landscape—the old tires baking in the sun, the big piles of plastic. Laredo recently discontinued trash pickup to many Webb County colonias; the community as a whole has failed these people, he says, not him.

The rain has kept the brush country green, and C. Y.’s land is exceptionally presentable when we reach it. He points out with pride the cattle and the scimitar-horned oryx he imported, the holding ponds and wetlands where birds gather. When we dip low over cactus patches, the wind and noise from the rotor blades send rabbits scurrying in every direction. C. Y. points out where his grandfather made his mark upon the land, building berms and diverting ponds. This is where Anna rode horses as a child with the grandfather who raised her, where a young C. Y. took his friends to swim. It’s what would-be Texas ranchers dream of.

We reach the place where the dump would go—pending the legal battles to come, as Anna and C. Y.’s neighbors weigh their options—the place where his generation will leave its legacy for future generations. A rail yard, a switching station, trucks and trains, recycling facilities, conveyor belts, methane vents, bulldozers, containment ponds, injection wells. C. Y. looks over the land. “My family started this community, and it will be here to the end,” he says. “Whichever way that goes.”