This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

One of the memorable experiences of my life was driving the back roads of Bavaria a few years ago, stopping at the small inns that Germans call Gasthäuser to sample the local beer, which was usually brewed on the premises and was unfailingly fresh and interesting. Along the way it occurred to me that this was an experience that couldn’t be duplicated in Texas, though at the time I wasn’t sure exactly why. One reason, no doubt, was the beer itself. In Germany, beer is brewed according to a strict purity law—Reinheitsgebot—that has been on the books since 1516. Brewers in Germany are permitted to use only four ingredients: water, malted barley, hops, and yeast. American brewers use a variety of cheaper, less flavorful ingredients, including corn, rice, and sometimes extracts of grains and hops.

The beer that I drank in Germany came in an amazing variety of styles, tastes, and aromas and was no more than a few days old, which meant that I sampled it at the peak of its freshness. Like bread, beer is best when it is first made. American brands can be virtually indistinguishable from one another: Ninety-two percent of the beer brewed in this country comes from six interchangeable megabrewers. Moreover, packaged beer, both domestic and imported, often has been shipped long distances and warehoused for weeks before being poured for consumption. The difference between drinking a glass of, say, freshly brewed Dinkelsbüler and a glass of Lone Star is at least as startling as the difference between eating a fresh French baguette and a slice of week-old Rainbow bread.

Yet the main reason that my Bavarian experience can’t be duplicated in Texas, as I have recently learned, isn’t beer but politics—a classic example of our good ol’ boy network in action. Gasthäuser—or brew pubs, as their American counterparts are called—aren’t legal in Texas. (One might say that in Germany good beer is prescribed by law, while in Texas the exact opposite is true.) Brew pubs are legal in 41 other states, though, and they are apparently popular and profitable for all concerned. They create jobs, raise tax revenues, stimulate investment and tourism, and even effect a modest increase in the export economy of every state in which they are permitted. Since brew pubs are restaurants first and bars second (people go there more to eat than to drink), they do not contribute appreciably to the problems of alcoholism. In fact, in their essential quest to create high-quality handcrafted beer, brew pubs encourage moderation. So why don’t we have them in Texas? The answer is that every time legislation to legalize brew pubs has been put forward in Austin, the effort has been crushed by the wealthy and powerful beer distributors lobby, which understandably doesn’t want the competition.

This spring, however, the beer lobby may finally lose its stranglehold on the issue. What is amazing is that it has taken so long: Brew pubs cannot by any stretch of the imagination be regarded as competition—either for distributors or for large brewers. Except that they sell food and beer on the premises, brew pubs are merely smaller versions of microbreweries, defined by federal law as breweries that produce no more than 60,000 barrels a year. Microbreweries account for only one half of one percent of the beer made in this country: Anheuser-Busch makes more beer in twelve hours than all the microbreweries make in a year. Because of our state’s tangled and arcane alcoholic beverage code, even microbreweries find it difficult to survive in Texas. Currently, only two exist, both of them relatively new: the Texas Brewing Company, which is owned by a retired oilman named Allan Dray and operates in the old Dallas Brewery building in the West End, and the Celis Brewing Company of Austin, which is owned by Belgian brewer Pierre Celis. Together they brew 20,000 barrels a year; by contrast, the massive Anheuser-Busch brewery in Houston produces 9 million barrels. And yet Anheuser-Busch pays to the State of Texas the same $1,500 yearly licensing fee that Dray pays and only one third of the fee paid by Celis, which shells out an extra $3,000 for a permit to brew ale.

The main difference between a brew pub and a microbrewery is economic vulnerability. A brew pub can make a profit by brewing about one thousand barrels a year; a microbrewery needs to brew five times that amount. The profit margin of a brew pub is as high as 70 percent. Unlike microbreweries, brew pubs don’t have to worry about the high cost of packaging, distributing, and marketing: a glass of beer can be produced for about 10 cents and sold for $1.50. As the Wall Street Journal has noted, a two-hundred-seat restaurant that adds a $250,000 brewery can triple its bottom line and pay for itself in two years.

“I’d close down in a second if I didn’t think we had a good chance of eventually getting brew pub legislation passed,” says Dray, who has invested more than $1 million in his brewery. Until recently, the chance was anything but good, but that is a situation that is changing fast. Brew pubs are an idea whose time has come, even in Texas.

Brewing is an integral part of our Texas heritage. We brew more beer than any other state in the country, a tradition dating back to the great German migration to the Republic of Texas in the 1840’s. The first German settlers found that the ale imported from the United States was too heavy for their taste and had the flavor of wet cardboard once it completed its long overland journey. Regional breweries soon popped up all over Central Texas—in LaGrange, Bastrop, Castroville, New Braunfels, Waco, Austin, and San Antonio. William Menger’s Western Brewery, on the grounds of the Alamo, was so popular that he later built a hotel next door to accommodate the brewery’s customers. Charles Nimitz, World War II hero Chester Nimitz’s grandfather, operated a brewery in the basement of his hotel in Fredericksburg. Skilled and innovative, the Germans sheltered their brew from the Texas heat by building breweries in cellars, insulated with mounds of earth and cooled by cold-water springs that were channeled beneath the brewing tanks. By 1866, Texas was home to 58 breweries.

The first outsider to penetrate the Texas market was Adolphus Busch, who in the 1890’s pioneered the manufacturing and use of refrigerated railroad cars to haul his beer from St. Louis. At about the same time, he purchased the Alamo Brewing Company in San Antonio for the purpose of shutting it down so that it couldn’t compete with his other brewing interests. Busch’s high-handedness was a harbinger of things to come. By the turn of the century, small breweries were falling victim to mass changes in transportation and merchandising, transitions that made it easy for the strong to gobble up the weak. Although there were still more than one thousand breweries in the country in 1935, mergers, bankruptcies, and forced liquidations reduced that number to a mere eighty by 1983. As late as the fifties, regional breweries of modest size were sprinkled across Texas, but only eight operate here today, six of them owned by giant brewers from outside the state.

While outdated laws have kept Texas in the Middle Ages, a renaissance of small breweries—and of good beer in general—has swept across the United States and Canada. It started in the early eighties, when states began amending Prohibition-era laws. In 1981 there were four microbreweries in the U.S. Today there are about three hundred, most of them brew pubs in a variety of styles, ranging from small neighborhood pubs to white-tablecloth French restaurants. They are especially popular in Colorado and California and along the Pacific Northwest.

The first microbrewery in Texas was the short-lived Reinheitsgebot Brewing Company in Plano, which began producing a good lager called Collin County Gold in 1984. The brewery was owned by Don and Mary Thompson, a pair of aging hippies who had fallen in love at Oktoberfest in Munich when he was a student at the University of Florida and she was a student at Texas Christian University. United by their love of good beer, they moved to Dallas, married, and began experimenting with home brew. After some success, they decided to start their own business. But the Thompsons soon realized that it was much easier to brew a good beer than it was to fathom the mysteries of the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Code or to deal with the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission (TABC), the huge state agency that enforces the code. “Nobody at the TABC had a clue how to deal with a small brewery,” Mary recalls. “If you asked them a question that could be answered yes or no, the answer was always no.” Under Texas law, any aged, carbonated, fermented, hop-infused extract of malted barley that has less than 4 percent alcohol is beer—even if it’s ale. Beer requires a manufacturer’s license, which costs $1,500 a year. Anything above 4 percent alcohol is classified as malt liquor (even if it’s ale, stout, or porter) and requires a brewer’s permit, at $3,000 a year. (In California the fee to brew anything is $65.) “We were passionate about making good beer,” Mary says. “We loved everything about beer—the history, the romance, the artistry, the people in the business. We wanted to make a heavier, more flavorful beer, but the code made that impractical. ”

Although financial problems forced the Thompsons to close down their brewery in 1989, the renaissance is showing signs of life in Texas. Sales of home-brewing equipment have doubled here in the past three years. (Home brewing wasn’t even legal in this state until 1983.) Beer lovers congregate in large numbers in pubs such as the Gingerman in Dallas, the Ale House in Houston, and the Dog and Duck in Austin, where dozens of exotic beers are available and hard liquor is not. The Gingerman, for example, features beers from 24 nations. On the shelves of my neighborhood market, Fresh Plus, three out of four beers on display are either imported beers or handcrafted beers from American microbreweries such as Samuel Adams, Sierra Nevada, or Celis.

As their numbers have grown, brew pubs and microbreweries have restored to the marketplace an astonishing variety of brews—bitter amber ales with complex aromas, malty bittersweet bocks, rich and creamy stouts with the aroma and color of darkly roasted malt, brisk and slightly hoppy pilsners. Brews are often crafted to local or regional tastes. A popular beer in Southern California is raspberry ale, made from fresh raspberries. One brew pub in Chicago makes an ale from oranges, and another is experimenting with cactus. The flagship beer at Austin’s Celis brewery is Celis White, a surprisingly refreshing wheat beer made from a recipe that has been brewed in Pierre Celis’ hometown of Hoegaarden for more than five centuries. Tart and spicy, the beer gets its aromatic taste from a seasoning of dried orange peel and coriander seed and its pleasantly bitter finish from two varieties of hops. To the purist, such offerings are not beer. “I group them as fermented fruit-flavored carbonated drinks,” says Mary Thompson, who now writes a column for the Southwest Brewing News under the pen name “the Queen of Quaff.” At the same time, Mary acknowledges that one of her great experiences in quaffing was when a brewer friend made up a batch of orange-chocolate stout for her birthday. “Now, that,” she says, “was a beer to die for.”

For years the Wholesale Beer Distributors of Texas has been able to squash brew pubs and other small business ventures by posing as a guardian of the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Code—which it is, but not in the way it likes to pretend. What most Texans don’t realize is that the code gives the beer distributors of Texas a legal monopoly. It protects them not only from territorial encroachment by other distributors but also from such competitors as brew pubs, which deal directly with consumers. Parts of the code date back to 1935, just after the repeal of Prohibition, when Texas and most other states adopted the so-called three-tier system that established protective walls between brewers, distributors, and retailers. The system was an attempt to outlaw the abuses of the early 1900’s, when beer barons such as Adolphus Busch and Joseph Schlitz owned or controlled most of the saloons in the United States. Under the three-tier law, brewers were no longer allowed to sell directly to consumers or retailers. In effect, the system institutionalized the middleman—the distributor or wholesaler. But in Texas, at least, a system that was supposed to protect us from the abuses of the industry has become instead an instrument to protect the industry from competition.

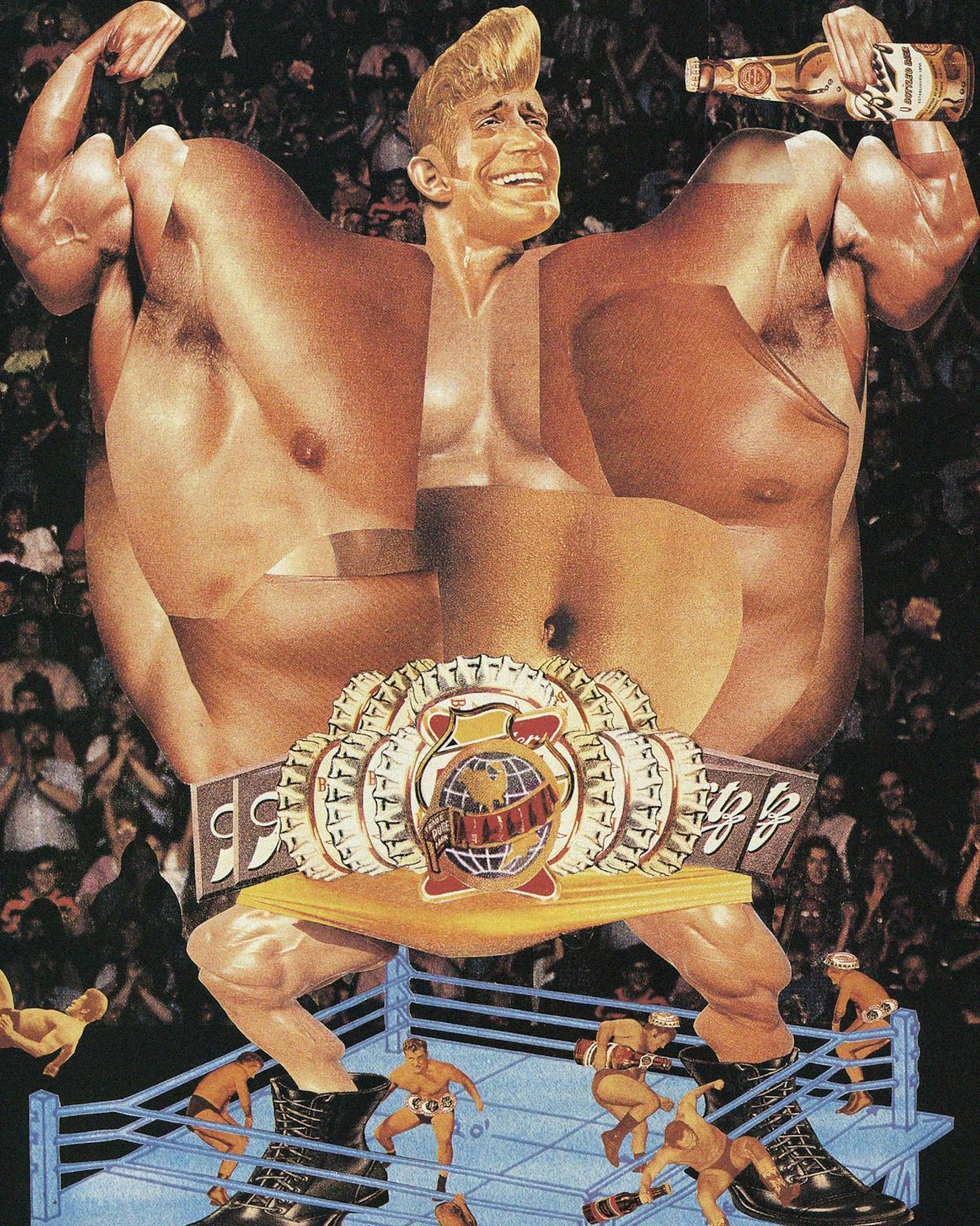

The three-tier system is the distributors’ crown jewel, and they secure it with corresponding tenacity. By contributing heavily to key members of the Legislature, who are already reluctant to upset the status quo, the politically savvy distributors make certain that any legislation affecting the three-tier structure must first pass muster with their chief lobbyist, Mike McKinney. A rotund balding man with a wreath of hair that makes him look like Friar Tuck, McKinney and his assistant, Butch Sparks, are known around the Capitol as the Booze Brothers. McKinney was hired in 1984, five years after the wholesalers were jolted by a serious breach in their three-tier armor. In the closing minutes of its 1979 session, the Legislature had passed an amendment known as the Shiner Exemption, permitting breweries that produce fewer than 75,000 barrels a year to distribute their own product.

In practice, the exemption has troubled the wholesalers very little, except for the danger that it poses as a precedent. For example, Spoetzl Brewery, which brews Shiner, quickly learned that establishing its own distribution network was not economically viable. Spoetzl now distributes less than 3 percent of its beer and is in the process of phasing out even that minuscule effort. The experience, however, impressed upon the wholesalers the lesson of eternal vigilance. In 1990, when Anheuser-Busch purchased Sea World in San Antonio and asked for an exemption so that the brewery’s product could be sold at the marine-life park, McKinney personally negotiated the language in the exemption. Brew pub proponents have been told by Capitol insiders that the only way they can get a bill through the Legislature is to first get approval from the Booze Brothers.

“Word around Austin is that the distributors can kill any piece of beer legislation with a few phone calls,” says Greg Carr, a Dallas attorney who represents the Texas Association of Small Breweries, one of the groups backing brew pub legislation. These groups have been pressing their case for six years, and each time, the Booze Brothers have stopped them. At times, though, brew pub supporters appear to have been their own worst enemies. Disorganized and politically naive, they couldn’t agree on a strategy or even decide among themselves what it was they really wanted. One group sought a simple amendment to the existing licensing section of the code, allowing brewers to sell food and beer for on-premise consumption only. A group headed by Texas Brewing Company owner Allan Dray wanted a brew pub law similar to the one in California, where regional breweries such as Sierra Nevada can operate pubs in conjunction with their brewing operation and distribute their beer wherever the market demands.

After two abortive efforts, brew pub supporters finally got a hearing in the 1991 legislative session. Witness after witness outlined the economic benefits of brew pubs and described how current regulations inhibited the establishment of microbreweries. Other than a representative of the TABC, only one person spoke against brew pubs—the lawyer for the beer distributors (presumably the Booze Brothers decided that a lawyer made a better front man than a lobbyist), who suggested that the proposed legislation put the code in peril. “As soon as he spoke, the walls started coming down around us,” says Davis Tucker, who brews the Austin beer Pecan Street Lager at a Minnesota plant because of the TABC’s restrictive rules.

Mike McKinney says that he has no problem with the concept of brew pubs; his concern is the sanctity of the three-tier structure. “People claim that laws are written to protect the industry, but in fact the purpose of the three-tier law is to protect the industry from itself,” he says, parroting the standard defense of the system as a guardian of good against evil. And yet last session McKinney pushed through a bill that gave distributors immunity from anti-trust laws, granted brewers indemnification from harm resulting from beer consumption, and made Texas Stadium wet despite the fact that the citizens of Irving had voted otherwise. The bill was subsequently vetoed by Governor Ann Richards, who saw it as a particularly egregious piece of special interest legislation.

Over the years the wholesalers have formed a cozy alliance with the TABC, one that benefits both parties and enables them to defend the code against outside assaults. (McKinney, in fact, used to work for the TABC himself.) Back in 1982, in response to a lawsuit filed against the TABC by Anheuser-Busch claiming that the Shiner Exemption discriminated against big breweries, the wholesalers jumped to the TABC’s defense, taking the position that the exemption had no significant impact on the beer business in Texas. Now that the issue is brew pubs, the wholesalers are making the opposite argument.

In exchange for this support, the TABC provides a number of services to the wholesalers, the most astonishing of which is the collection of their bad debts. Under the code, retailers can’t purchase beer on credit: They must pay on delivery, a requirement that penalizes less affluent retailers. If a tavern owner or convenience store proprietor writes a bad check to a wholesaler, no matter how innocently, the TABC fines him or suspends his license. A black convenience store operator in Dallas who had three checks returned—one because the bank made a mistake and another because the check bore his wife’s signature instead of his own—was offered a choice between a fifty-day suspension or a $7,500 fine. A survey by the Houston Chronicle reported that the TABC spends far more of its time and money punishing retailers who owe money to wholesalers than it does enforcing all other liquor violations. Moreover, the TABC enforces its rules selectively, primarily punishing those whom the distributors find most troublesome. “Beer distributors get away with murder,” one TABC agent told the Chronicle.

So does the TABC. For years retailers have complained about arbitrary, sometimes thuglike treatment at the hands of TABC agents—the Booze Police, as they are sometimes called. There have been complaints, too, about the agency’s hiring practices and allegations of sexual harassment. A number of critics, including comptroller John Sharp’s budget-cutting Texas Performance Review staff, have suggested that the TABC be dismantled, that its law enforcement duties be transferred to the Department of Public Safety, and that its tax collecting and auditing responsibilities be turned over to the office of the Comptroller of Public Accounts, which audits and collects the taxes of other types of businesses. Complaints of unfair and arbitrary treatment by TABC auditors are common. “When the TABC audits you,” says Richie Jackson, the president of the Texas Restaurant Association, “they don’t look at your books and records; they look at your invoices and estimate how many mixed drinks you sold.” In other words, a $5 bottle of whiskey becomes, in their eyes, a $25 bottle—$5 for the bottle of whiskey and $20 for the tax on the 26 drinks that came out, even if the bottle was lost or stolen.

Though it is possible to appeal a TABC decision, the process is slow and the burden of proof is on the defendant, who must pay the fine or tax levy before filing the appeal. “We are forced to prove a negative—that we didn’t sell something,” says Jackson.

Despite a constant stream of complaints from retailers across the state and across the industry—from grocers, liquor-store owners, bartenders, hotel and restaurant proprietors—the TABC for years escaped review from the Sunset Commission, the state agency that periodically determines whether other agencies are doing their jobs. From 1979 until 1992, the TABC was one of just two agencies that avoided the review process; the other was the DPS. Everyone at the Capitol knows why. Each time the Booze Police have been scheduled for Sunset review, the Booze Brothers have found friendly legislators to push through a postponement.

At least until now. This spring, the sun finally threatens to set on the TABC, a prospect that will subject not only the agency but the code itself to reexamination—and, by the way, will open a narrow path for brew pubs. The TABC was called for Sunset review last summer, at which time the Sunset Commission determined, among other things, that laws prohibiting brew pubs “inhibit establishment and growth of the small brewing industry.” A lengthy bill now before the Legislature would give the TABC another twelve years of life. Included within that package is a section that would permit breweries to sell food and beer for on-premise consumption but would not extend the Shiner Exemption to include heavier beers.

This time around, brew pubs have a fighting chance for two reasons. First, the brew pub advocates are much better organized. Houston oilman and developer George Mitchell, who wants to locate a brew pub on the Strand in his native Galveston, has joined forces with microbrewers in Dallas and Austin. Former House Speaker Billy Clayton represents another group. Greg Carr and his Texas Association of Small Breweries are two years older and far wiser. Any number of brewers have plans in the works. Davis Tucker wants to bring his Pecan Street operation home to Austin and introduce an extra special bitter called Tipton’s, honoring his distant grandfathers and using a recipe they used at their own Tipton’s brewery in sixteenth-century London. Dog and Duck owner Bill Forrester is scouting locations for a brew pub in downtown Austin. The owners of the Menger Hotel in San Antonio want to reopen the old brewery, using some of the original equipment, which is stored in a Menger family barn. And a developer in Fredericksburg wants to start this state’s first Gasthaus.

The second reason why we may see brew pubs in Texas is that the Booze Brothers are finally giving ground. Brew pubs per se have never been the issue; what scares the wholesalers most is a full-scale review of the TABC code. If the brew pub advocates sufficiently press their case, a review would be required. Then, every issue of liquor regulation would be subject to amendment, debate, and vote—including the sacred three-tier structure. The Booze Brothers will do anything to avoid such a scenario. “They’re afraid that their whole house of cards will collapse, and that’s what it is—a house of cards,” says Bill Wells, the director of the Sunset Commission.

Confronted with the inevitability of brew pubs, the Booze Brothers have gone to the extraordinary length of drafting their own version of brew pub legislation. So in all likelihood, brew pubs are coming. Even so, the three-tier structure will remain. “Dismantling it would affect a whole series of business conditions in this state,” Wells says. “Maybe that would be good. I don’t know. But the system is as much a part of the landscape as the Grand Canyon. I doubt that at this late stage you can reclaim the land.”

Most Texans would settle for reclaiming their right to drink good, fresh beer.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Business

- TM Classics

- Texas Legislature

- Longreads

- Beer