This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

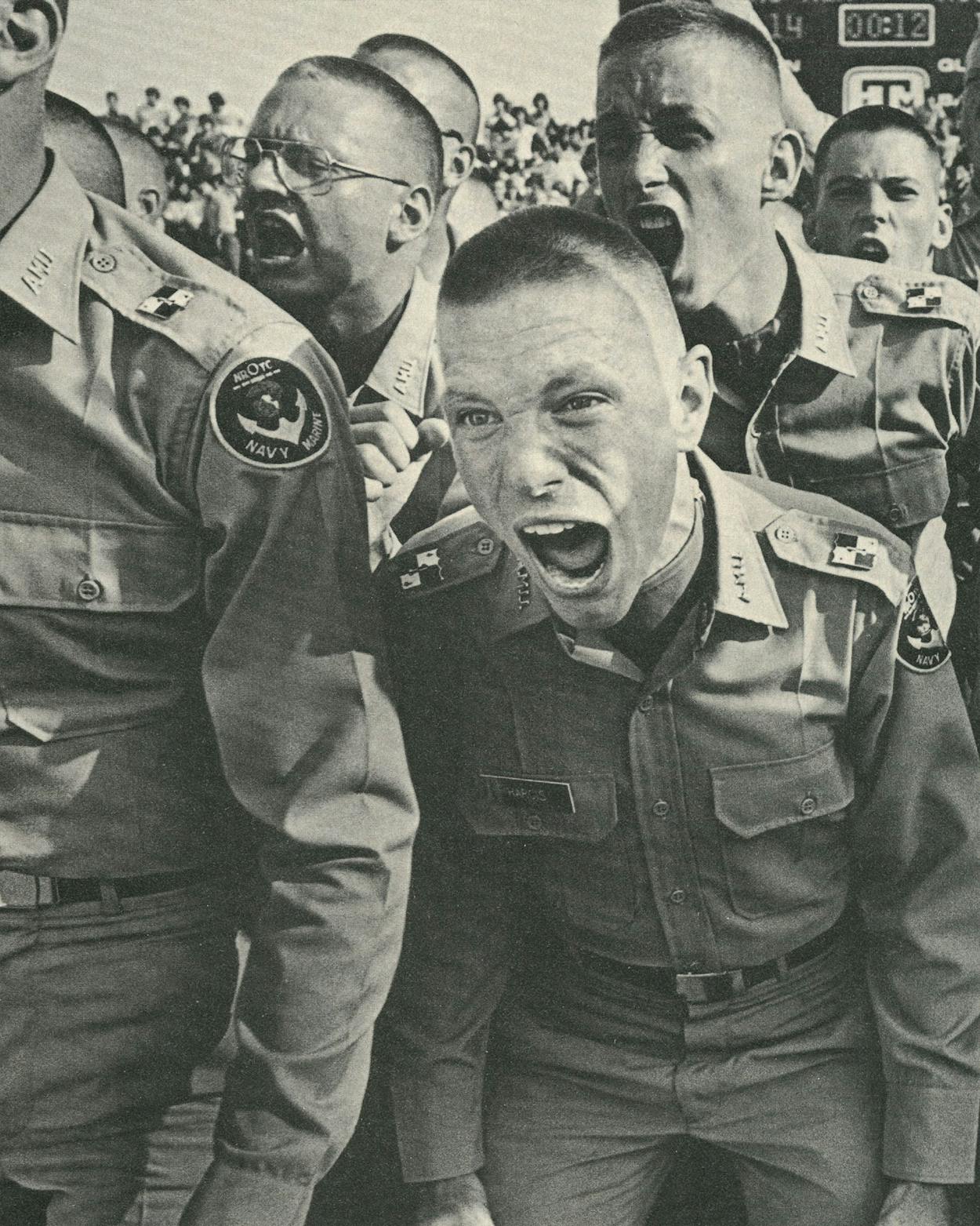

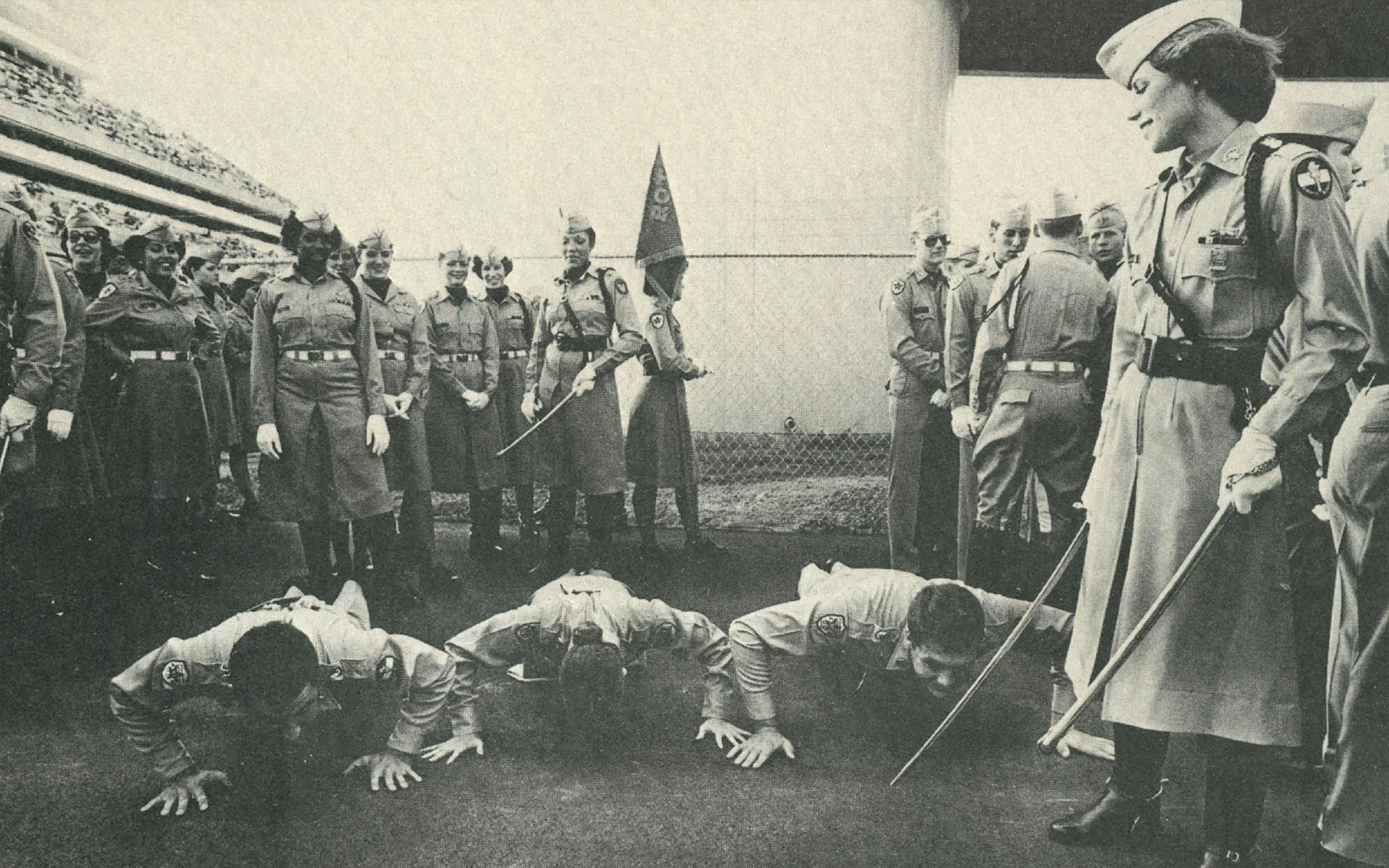

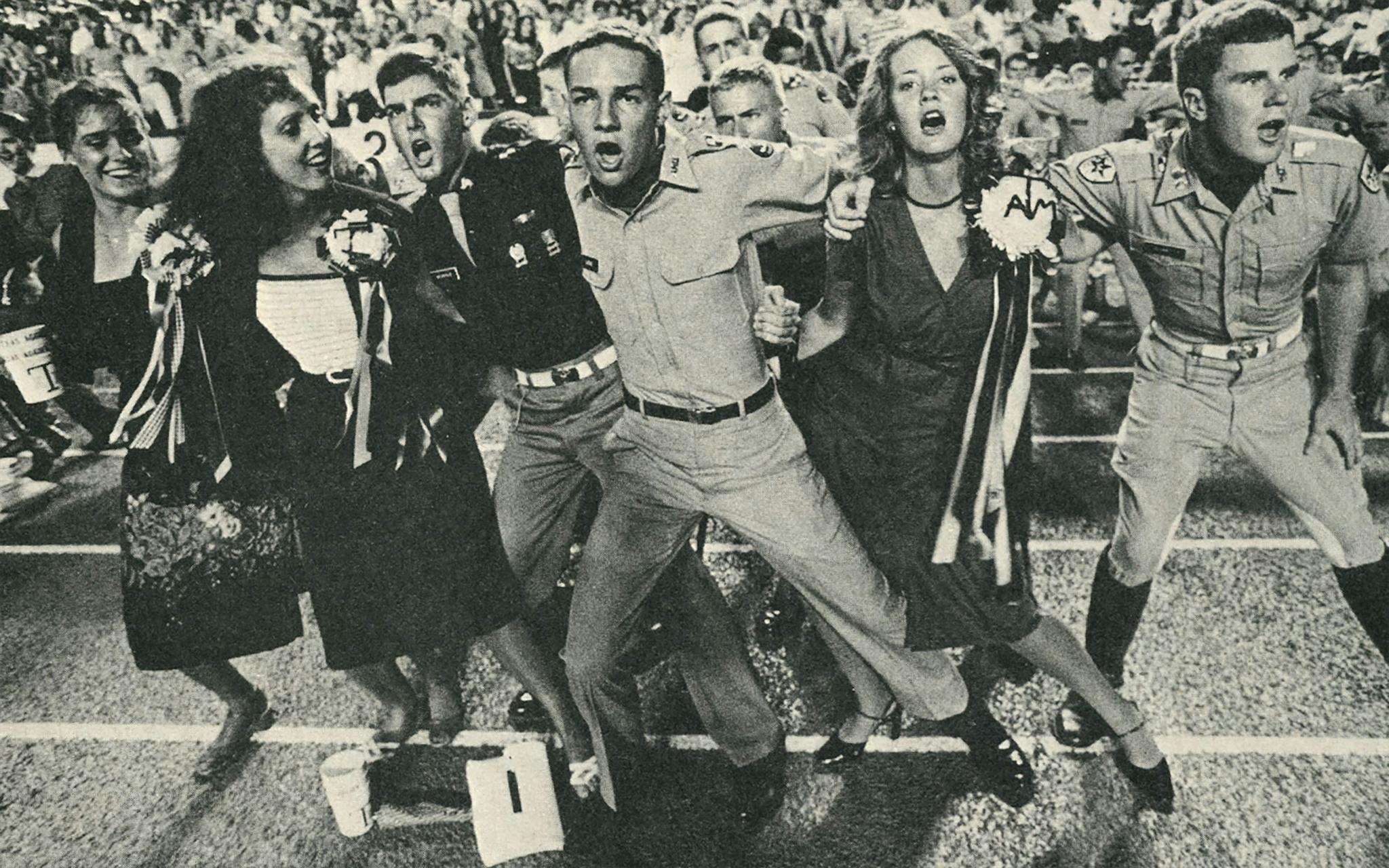

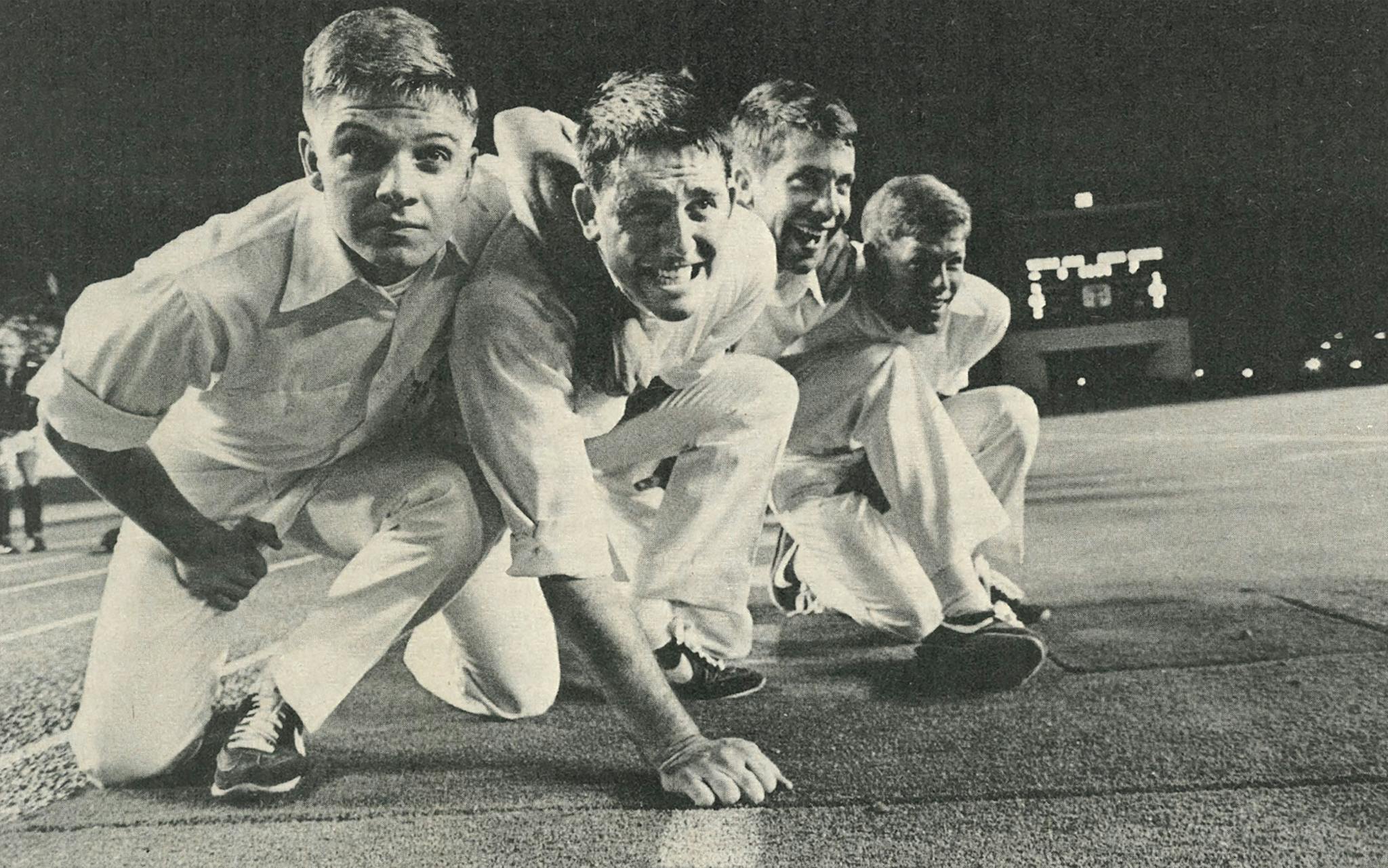

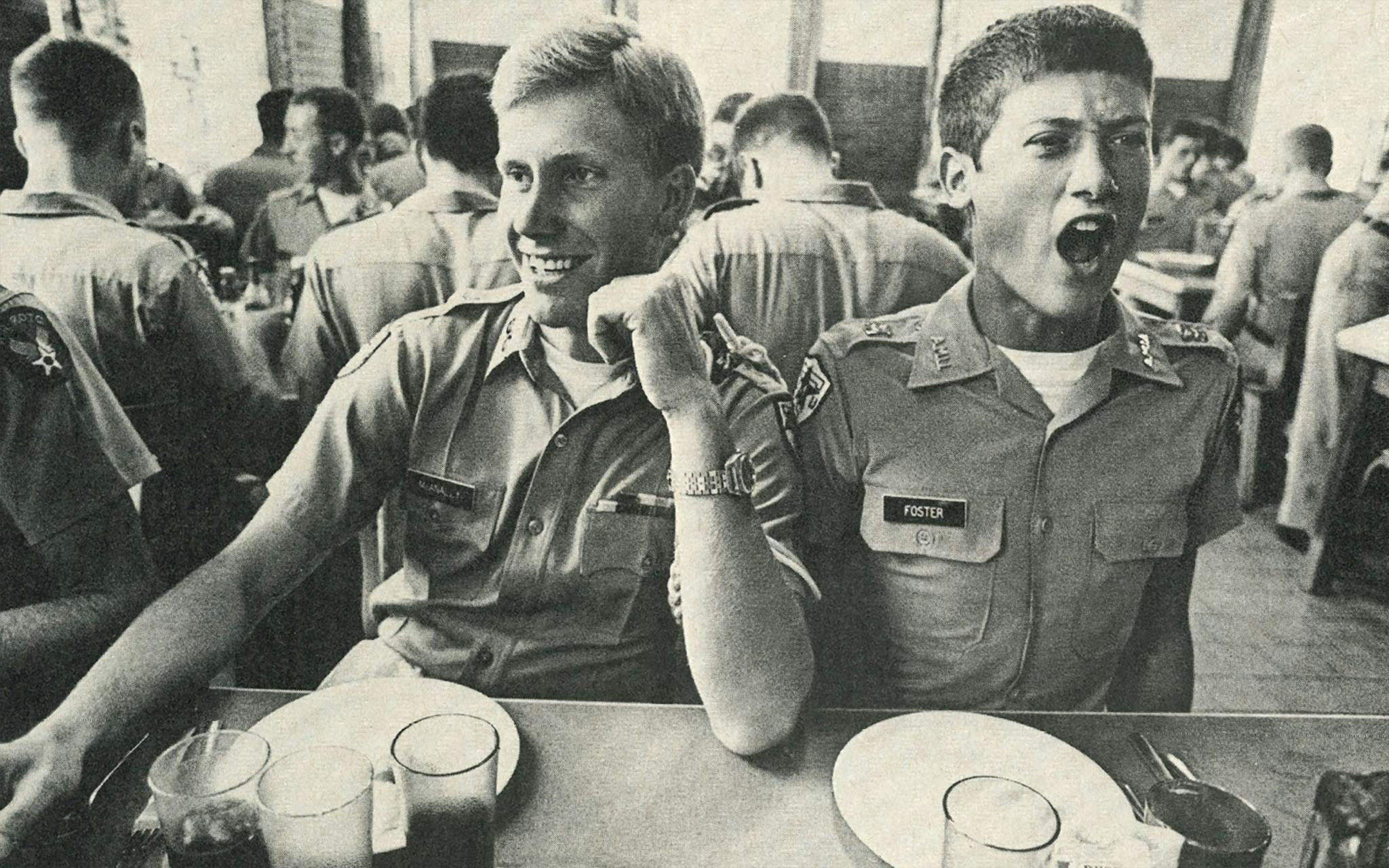

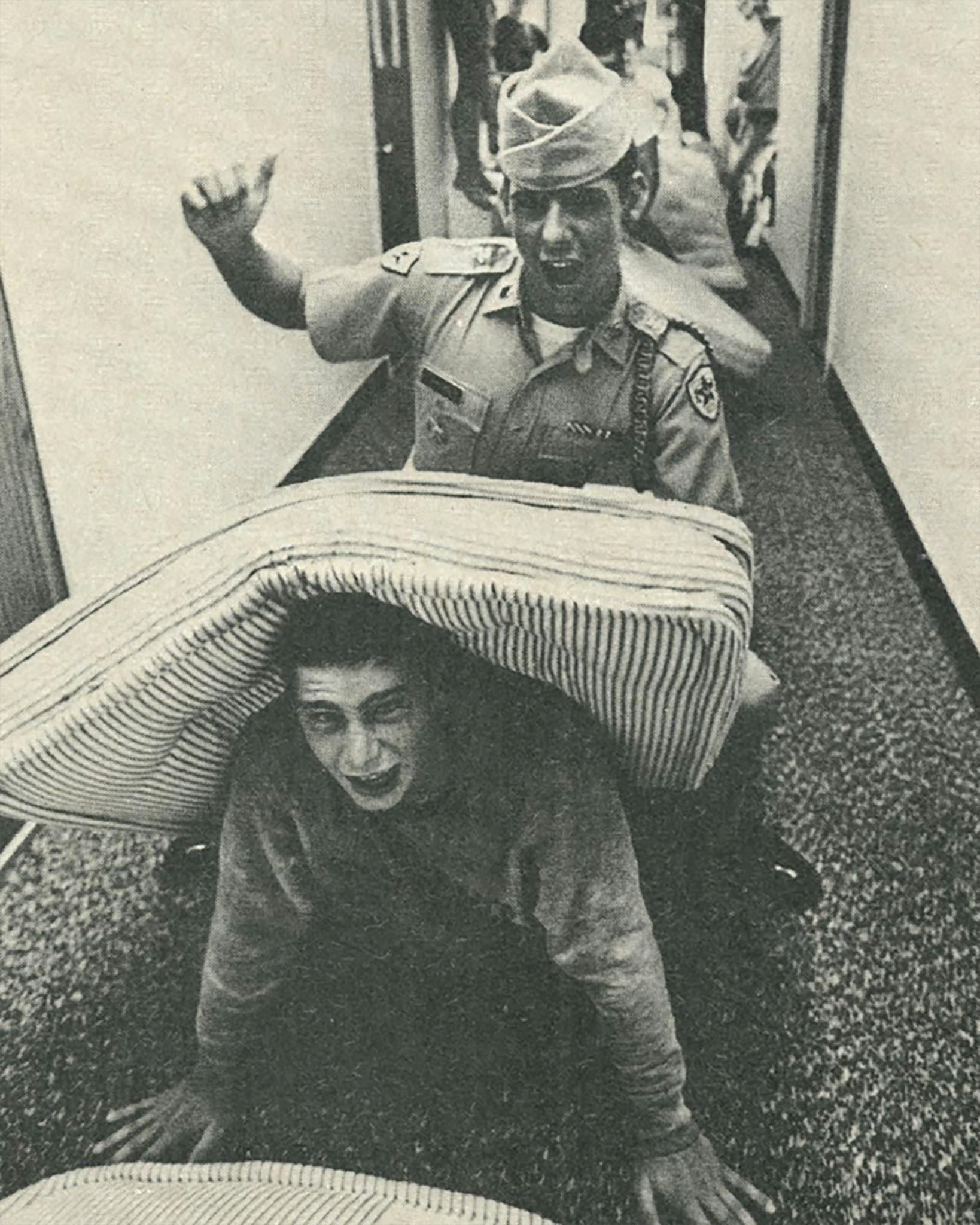

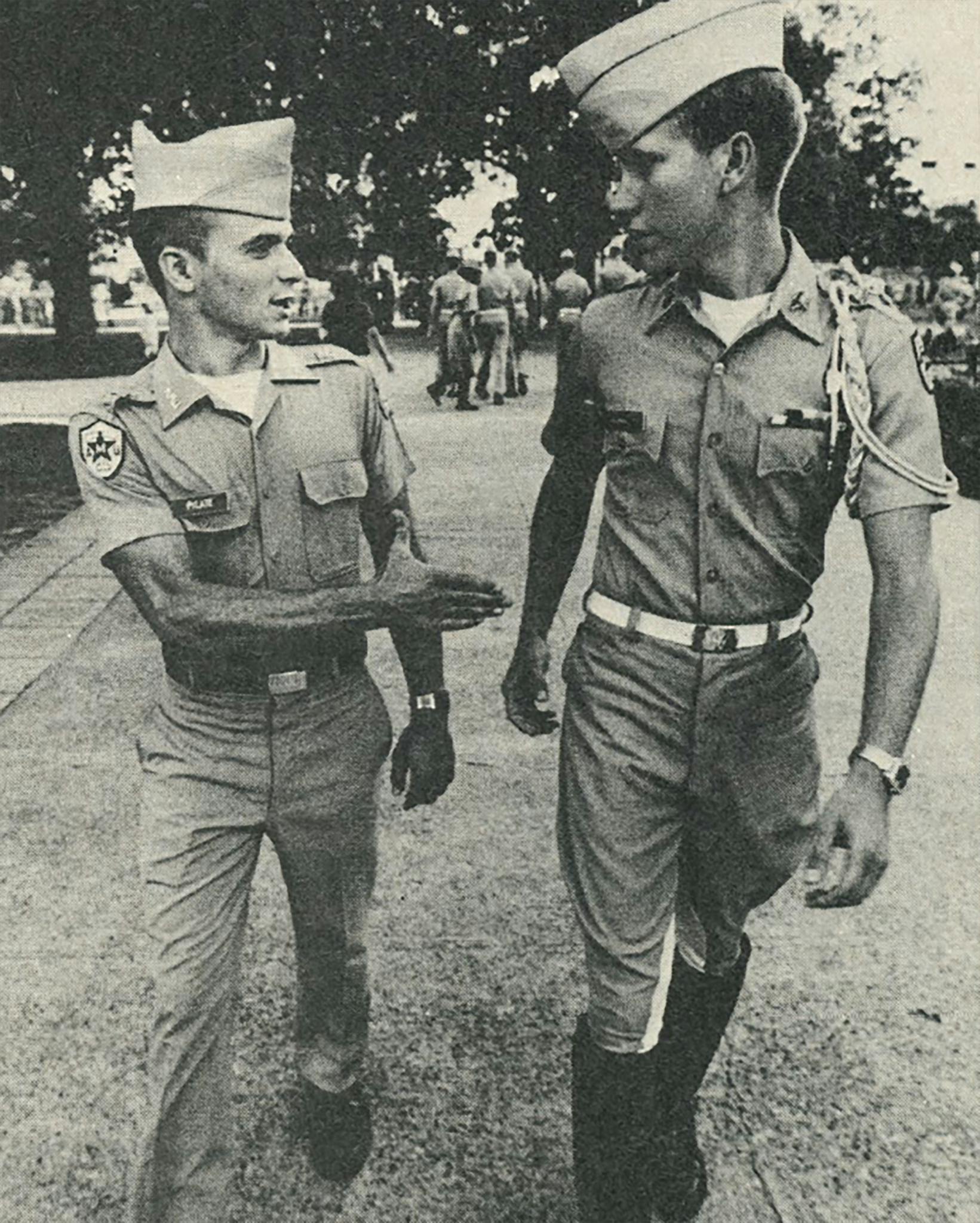

As an Aggie myself, I can tell you that the people in the photographs on this and the following pages are all being Aggies. None of them are faking it. Nobody can fake being an Aggie. It has to come naturally to you, which is just another way of saying that Aggies are born, not made. You can develop and strengthen your innate Aggieness, as these cadets are doing. That’s the reason they’re at A&M.

Which doesn’t mean they aren’t looking for a regular college education, too. Nobody ever went to A&M who didn’t already know he needed to get smarter. If you came out of a Texas high school with any pretensions at all, you went someplace else: if you had social pretensions you went to SMU; intellectual pretensions, to Rice; spiritual pretensions, to Baylor; or if you had an arrogant bent in no special direction you went to t.u., the place in Austin with the Day-Glo tower. All these schools are designed to encourage your illusions, to make you believe you’re something you’re not. Aggies have no illusions. We know we’re Aggies, we know we need to go to A&M to develop the fine points of our character, and since a school motto is “Once an Aggie, always an Aggie,” we know what we’re going to be doing for the rest of our lives. Aggies are certain in an uncertain world. And that’s why the uncertain world makes so many Aggie jokes—they’re jealous.

Old-timers will tell you there wasn’t any such thing as Aggie jokes before the twenties. In fact, there weren’t even any Aggies. People who went to A&M were known as Farmers for the first fifty years of the school’s existence, which began in 1876. A&M was Texas’ land grant college—thanks to the Morrill Act, this country’s grand adventure in public higher education. Other states got land grant colleges, but none of the others have turned out anything like Texas A&M.

A&M means Agricultural & Mechanical, two of the fields of practical study called for in the Morrill Act (military science was another), but there wasn’t much need for mechanical learning in nineteenth-century Texas. So “Farmers” it was. After a good fit of logrolling, a governor’s commission decided the school belonged in an elbow of the Brazos River, the river that cuts like no other across the land and the saga of Texas; the Indians, the Mexicans, and Stephen F. Austin all regarded it as special, lived alongside it, or died for it. Old Sam Houston himself, whose youngest son was in A&M’s inaugural class, once claimed that the country was the finest farmland on earth. For a young man wanting to study the way things grow, then, here was a laboratory second to none.

So it was later, during the Roaring Twenties, that advanced, college-educated farmers began thinking of themselves as members of the agricultural profession. At least that was when “Aggies” began replacing “Farmers” as the term for young men (strictly men, back then) who went to A&M. And that was also, perhaps not coincidentally, when Aggie jokes were born. They started to get voguish in the thirties, and by the fifties they were hugely popular.

Since then the Aggie reputation has grown into something just shy of mythical—as large and colorful as the Texas imagination, as unique and unpredictable. The Aggie of the jokes is the terminal bumpkin: outclassed in any company, over his head in every situation, blissfully gullible, relentlessly horny. He is easy to please, slow to catch on. Sort of like Steve Martin playing John Wayne, except bigger and X-rated.

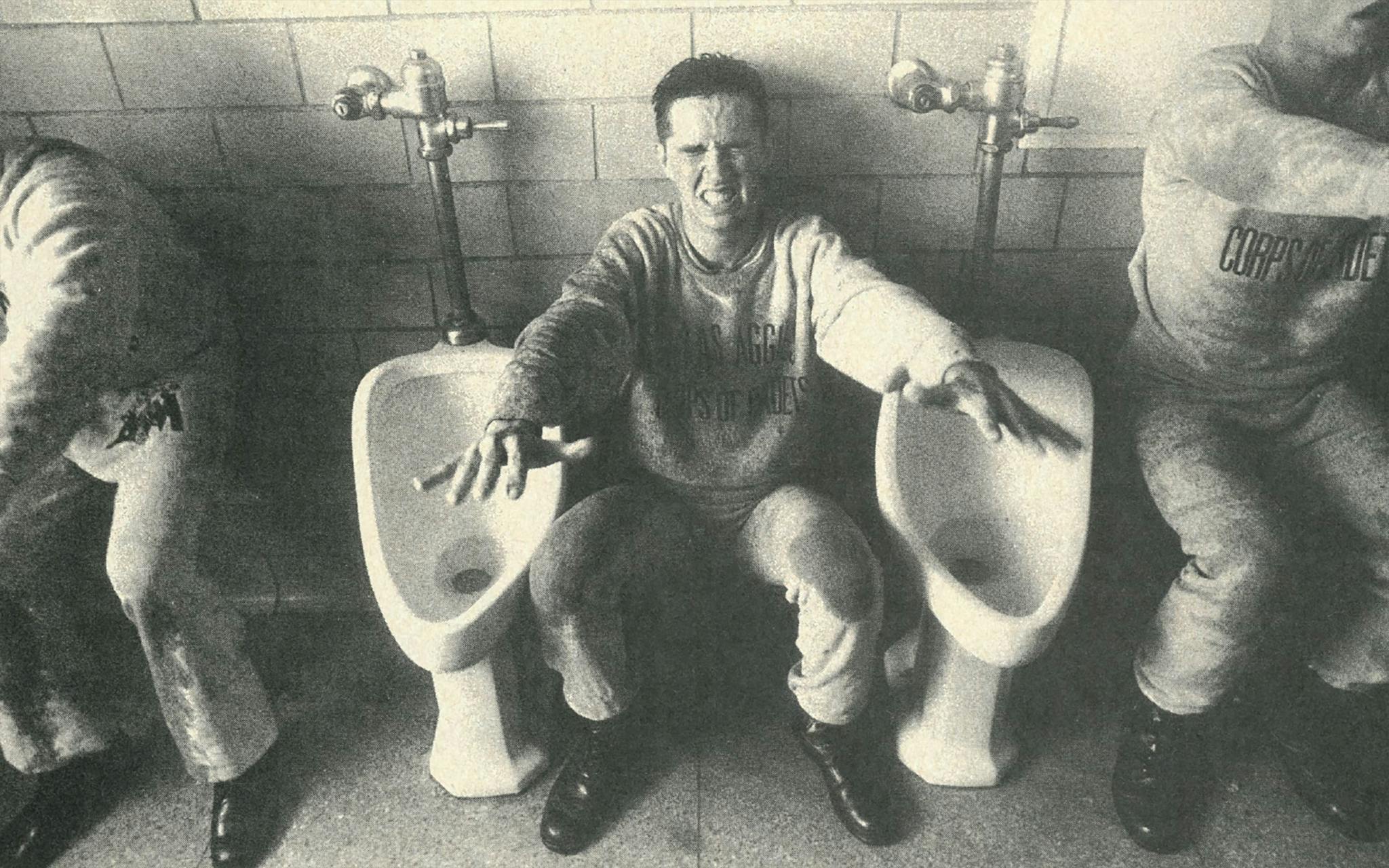

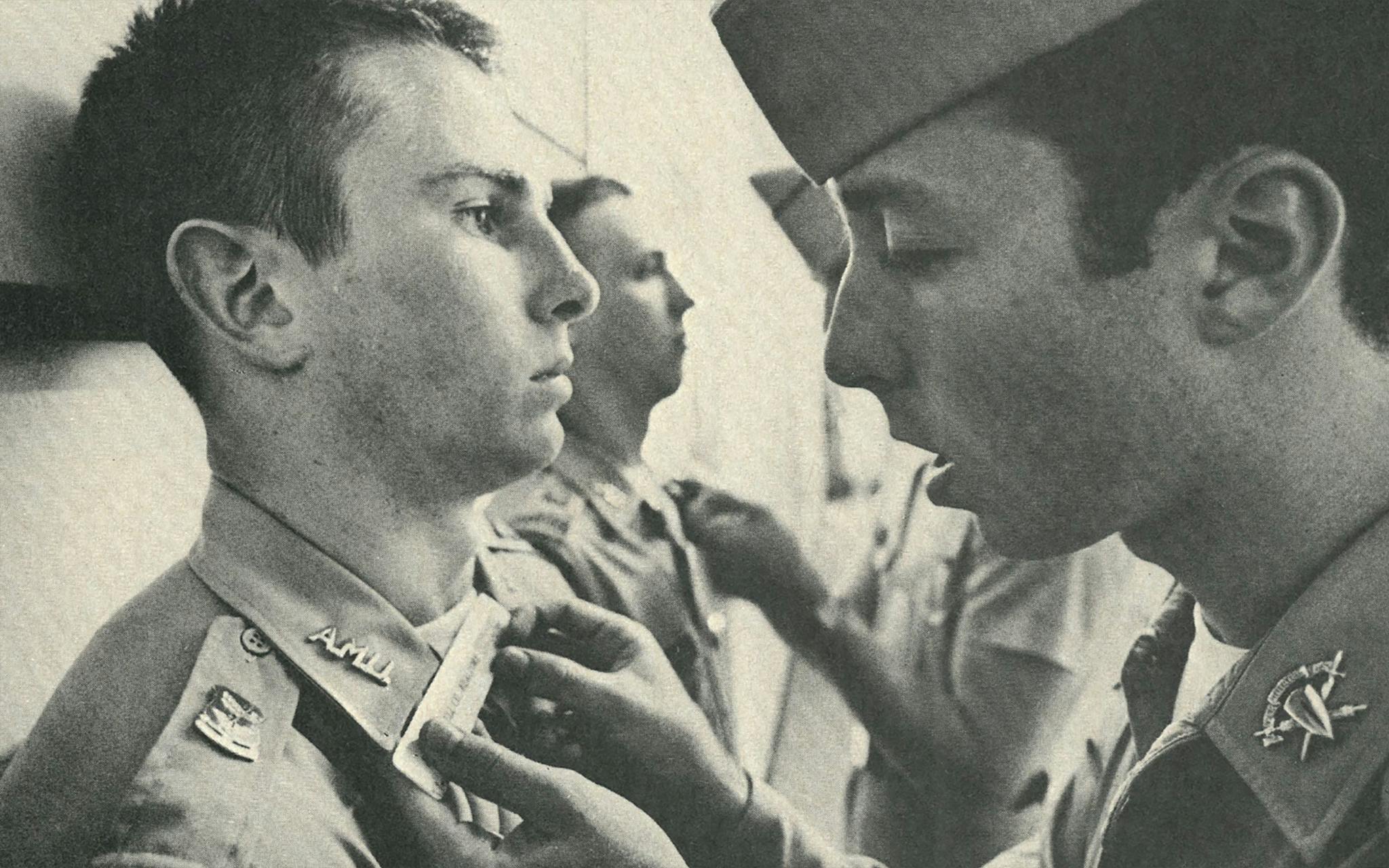

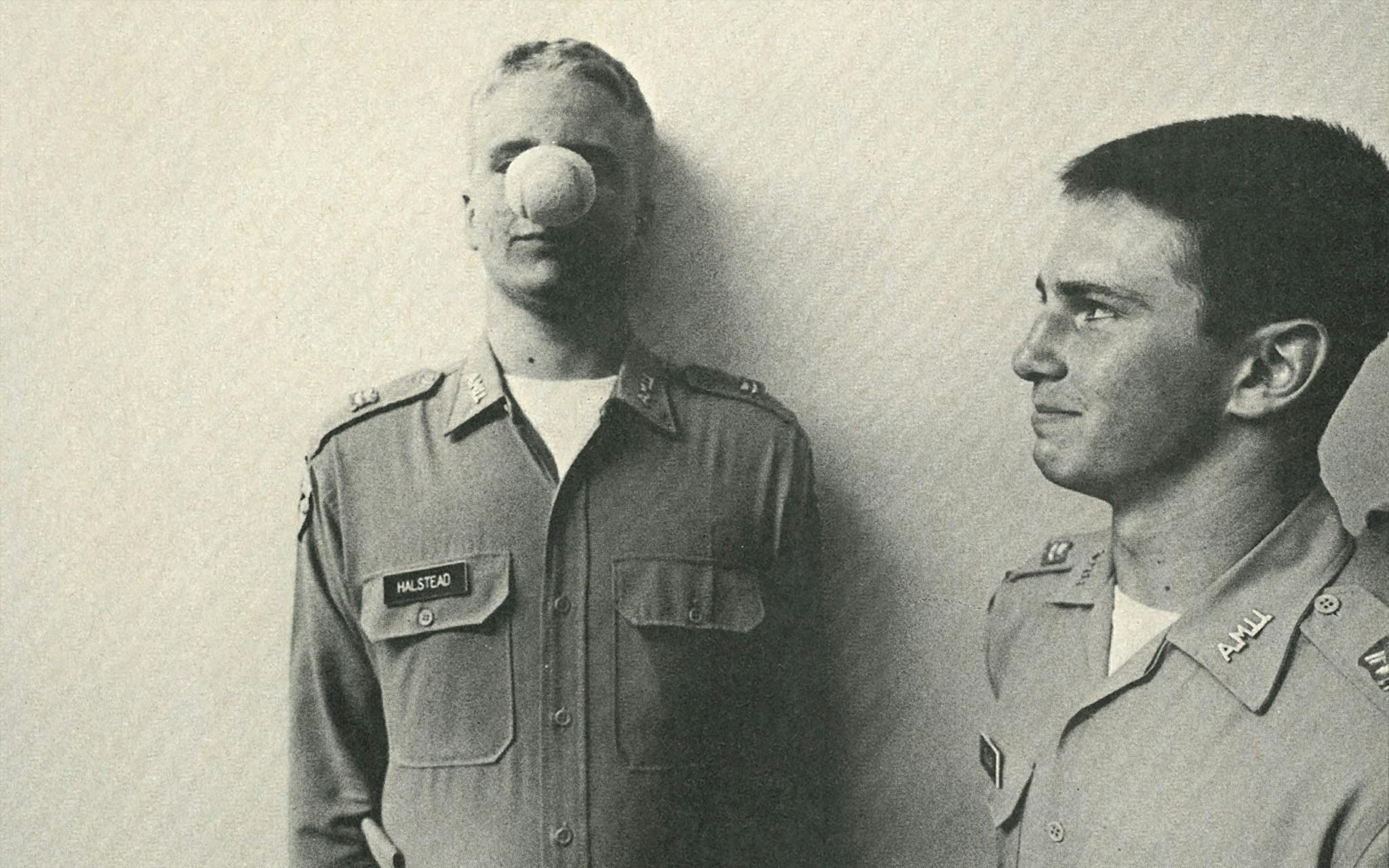

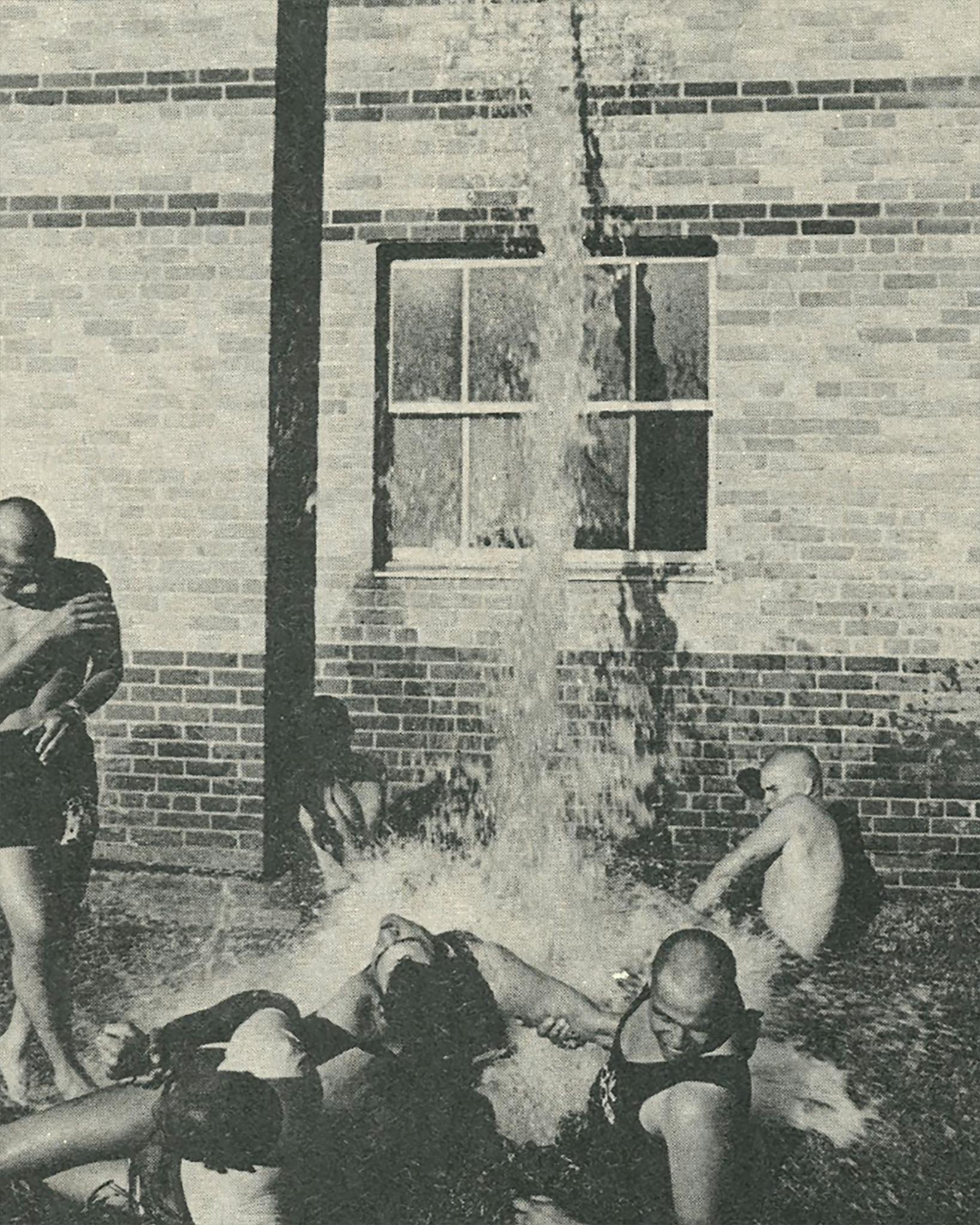

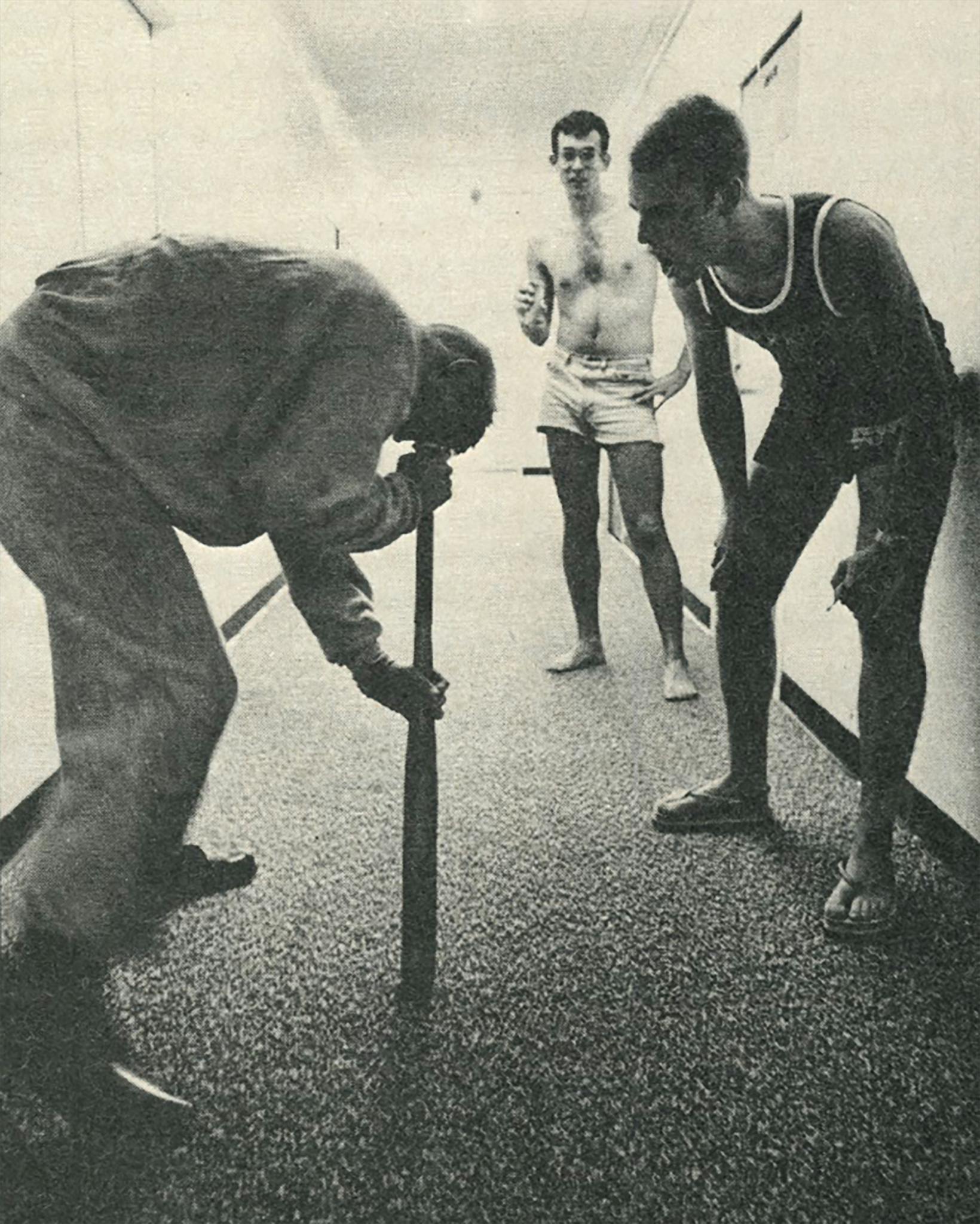

Imagine the burden of living up to a reputation like that. It isn’t easy, I promise you. We’re somehow expected to behave in uniquely ridiculous ways, totally uncalled-for ways, in absurd and obscene and laughable ways. Texans everywhere are depending on us. It’s a never-ending challenge, a challenge we Aggies are born to meet. But we’re trained for it during our four years at A&M. These photographs all show important Aggie rituals or traditions—quadding, whipping out, catching butterflies, watching the bonfire, and the rest. To all you t.u. graduates and Rice intellectuals and SMU beauty queens and Baylor saints, these rites of Aggiedom may look just like what you thought Aggies would do. But to Aggies, all this looks normal. Campus legend, honored by repetition to each incoming class, is that these rituals help bring the cadets together, form bonds of camaraderie and spirit that will never be broken. Maybe they do, or maybe they do something else entirely. I just know that they are the crucible of Aggiedom. Beyond that I can’t say. I’m an Aggie. To be an Aggie is not to wonder why.

- More About:

- Aggies

- College Station