No beast on this planet eats bitter produce, unless forced by dire circumstance. But man eats grapefruit, and therefore is no beast. Grapefruit is bitter because it contains a flavonoid called naringin, one of many bad-tasting compounds Mother Nature created to protect plants from hungry animals and to let animals know which plants are likely to hurt them. Naringin can, in fact, hurt us: it interacts in unpredictable ways with many common medications, including antihistamines and blood-pressure drugs. Yet humans, perversely, have developed a taste for bad tastes, coffee chief among them, along with beer, which tastes, smells, and looks like urine, and scotch, which tastes like mossy wood. Nonetheless, there is a limit to how much bitterness the average person can tolerate, which is why grapefruit is typically leavened with a naringin-masking antidote at the juice factory or with a sprinkling of sugar at the breakfast table. Except in Texas, of course, a magical land where, among other blessings bestowed upon us by the partnership of God and Texas A&M, grapefruit is red, not pink or white, and almost always sweet.

The Rio Red Grapefruit grown in Texas is so sweet because it is naturally—using that word in the loosest possible sense—low in naringin. This, along with an alluring hue that draws shoppers to the produce section like bees to a honeysuckle bush, is why the Rio Red is widely considered the world’s best grapefruit. Florida grows a lot more grapefruit than Texas, but much of the Sunshine State’s annual harvest consists of pink and white varieties bound for the juicing plant. Our fruit is meant to be eaten right out of the peel, which means that the Texas grapefruit business is very much a beauty contest. Every fruit has to be plump, unblemished, and virtually seedless, and the color has to be just so: gold with a warm red blush on the outside and a deep, pleasing ruby red on the inside. The red varieties developed in Texas—where all red grapefruits originated—are legendary in the citrus industry. Budwood from Texas nurseries was used to create a red grapefruit industry not only in Florida and California but also in South Africa, India, and Australia. In 1993 the red grapefruit, which is by far the biggest fruit or tree nut commodity in Texas, was named the official state fruit. It has become an icon of Texas at its best, like boots or bluebonnets or Big Tex.

How Texas came to have the world’s most coveted grapefruit is a story that begins with a little luck during a very unlucky time. In 1929, on the eve of the Great Depression, a McAllen grower named A. E. Henninger noticed a fruit with a curious red blush on one of his Pink Marsh grapefruit trees, the kind of natural mutation—known as a “sport”—occasionally found in all orchards. Most sports are barely noticeable, but this one was startling. The flesh was ruby red and much sweeter than any grapefruit the grower had ever tasted. Henninger carefully cut fresh new buds from the branch bearing the mutant fruit and grafted them onto other trees, which began producing red fruit as well. The sweet new variety put the Rio Grande Valley on the map and resuscitated a moribund industry, not only in Texas but also in Florida and California. In the years that followed, similar mutations were found across the Valley, and soon each grower began developing his own strain of red fruit, named, inevitably, for himself. (In the mid-thirties, you could buy a box of Shary Red, Curry Red, Fawcett Red, or Webb’s Redblush Seedless.) Henninger eventually patented his variety—the first citrus patent granted in the United States—under the name Ruby Red, and that moniker was soon attached to all Texas red grapefruit.

Since the cloned trees took years to mature and bear fruit, developing and perfecting new varieties was a painstakingly slow process. That began to change in the sixties, when a researcher named Richard Hensz started irradiating seedlings in his lab at the Citrus Center, in Weslaco, a research arm of the old Texas A&I system. Suddenly there were dozens of new mutations, which Hensz carefully culled and tested in the decades that followed, in a never-ending quest to find the perfect grapefruit. In 1984 he unveiled the Rio Red, the culmination of his life’s work and the new standard in grapefruit perfection. By 1990 almost every orchard in the Valley was planted in Rio Red, and Texas grapefruit was the envy of citrus growers the world over.

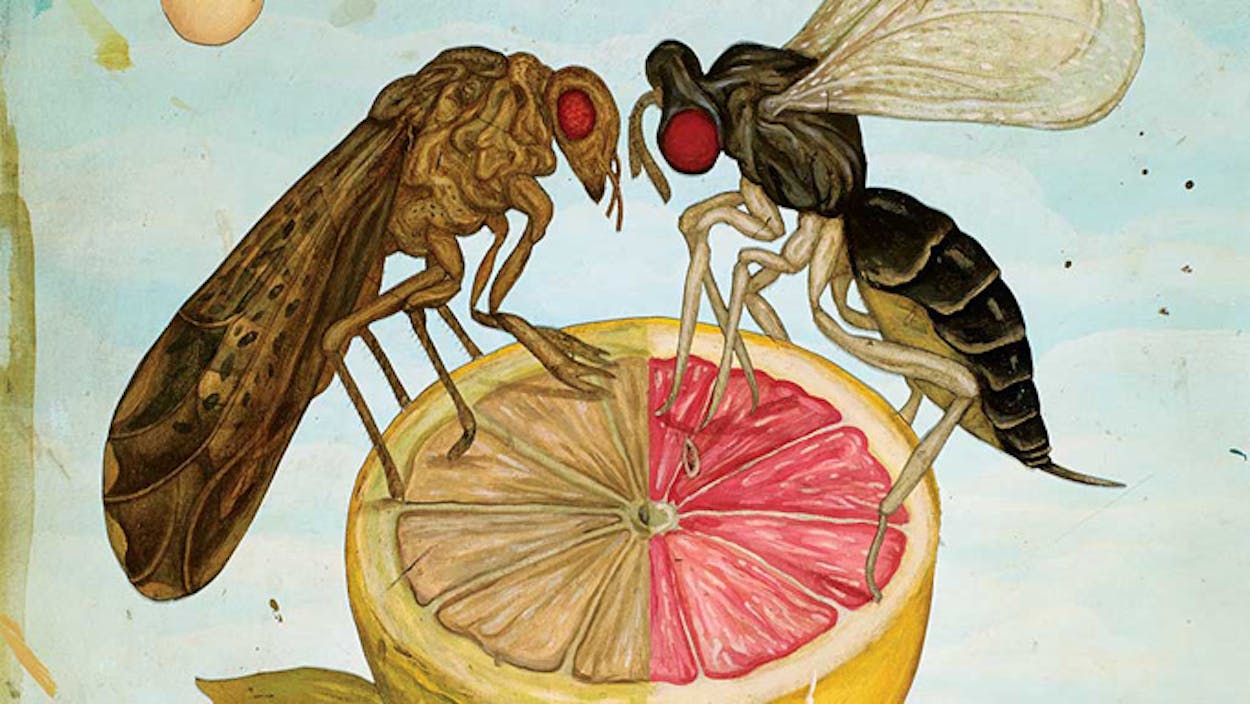

But nothing gold—or in this case, red—can stay. There is a lot that can go wrong in the citrus business—rust mites, mealybugs, foot rot—but since 2006, Valley growers have been fixated on a single threat that dwarfs every other: Huanglongbing, better known as citrus greening disease. The pestilence is caused by a bacteria that is spread by the Asian citrus psyllid, a tiny, aphid-like bug that seems destined to replace the boll weevil as the state’s most hated insect. Citrus growers in other parts of the world have long contended with greening disease, but it did not hit the United States until 1998, when psyllids from South Asia began showing up along the east coast of Florida, like a million miniature Godzillas rising from the sea. By 2006 citrus greening had exploded in groves all over Florida.

There is no cure for the disease, which chokes off the arteries that carry nutrients to a tree’s leaves and fruit. Florida lost thousands of trees in that first year, and total industry losses since 2006 have exceeded $3.6 billion. Florida citrus was quarantined, but the psyllids continued to spread across the country, and growers in Texas decided their only option was a massive preemptive strike. They embarked on a highly coordinated campaign of heavy pesticide spraying, in the hopes of forestalling for as long as possible the inevitable day when infected psyllids established a beachhead in Texas. On January 13, 2012, the day the Valley had been dreading for years finally came. A grower in San Juan spotted a sick citrus tree in one of his groves. The fruit was undersized and misshapen, the leaves yellow and sickly. Thirteen similarly afflicted trees were subsequently found in the same orchard and one nearby. Greening had arrived.

Since then a fascinating, Lilliputian confrontation has been unfolding in the placid groves of the Valley. You wouldn’t know it from a stroll through the produce section of your grocery store, where beautiful red grapefruit is as abundant as ever, but the state’s grapefruit orchards have become a battlefield, and nothing less than the future of a Texas icon is at stake.

On a warm morning in September, a grower named Dennis Holbrook gave me a tour of his grapefruit groves, which cover roughly five hundred acres in and around the town of Mission, on the west side of McAllen. Holbrook, who wore a blue-checked shirt, jeans, and tennis shoes, chairs one of several committees formed in recent years by Texas Citrus Mutual, the Valley’s venerable citrus growers’ association, to lead the fight against greening. “It’s what we go to bed worrying about and what we think about when we wake up,” he told me. Holbrook has been in the business since 1973. His family came to the Valley in the mid-fifties, when his father, the youngest in a large clan of Utah farmers, met a land promoter hawking the virtues of the Valley’s mild winters and long growing season and agreed to drive down and take a look. “In Utah, they’d had an early winter, and there was snow on the ground already when they left,” Holbrook said. “He came down here, and there were palm trees and bougainvilleas and fruit on the trees, and it looked like a paradise compared to where he came from.”

The notion that the Lower Rio Grande Valley could be marketed as something akin to paradise was the brainchild of a real estate investor from Nebraska named John Shary. In 1914, after visiting the few small grapefruit groves then in operation and spotting the potential of the still-nascent industry, Shary bought 16,000 acres of Valley brush. He dug irrigation canals from the Rio Grande and established the first large commercial grapefruit operation, but he was a real estate man at heart, not a grower. His big idea was to buy the land, plant it in citrus, and then sell off as much as he could in five- and ten-acre parcels to farmers in the Midwest. Most of these farmers didn’t move to the Valley, or at least not right away. They hired Shary to manage their small operations until they were ready to retire to their little corner of Eden.

Assuming none of the risk, Shary did well in good years and bad. Such acumen, first in real estate and later in banking, eventually made him a fabulously wealthy man. He built a mansion on his enormous estate near Mission, which he called Sharyland. (A portion of it today has been subdivided and sold off for a development called Sharyland Plantations.) Interestingly, the model Shary introduced meant that citrus farming in the Valley never took on the giant agribusiness quality it did in California and Florida, where a handful of companies controlled huge tracts of land. There were instead lots of small operations, some of which banded together to build a cooperatively owned packinghouse, still in business today.

In 1937 Shary’s only child, Marialice, married a young state senator and attorney from Port Arthur named Allan Shivers. An ardent New Dealer in his early career, Shivers came to see the world differently after marrying into the landed gentry. Oil money was underwriting most political careers in those days, but Shivers managed to ride his father-in-law’s grapefruit empire all the way to the Governor’s Mansion, where he remained for a then-record-setting term of seven and a half years. His most lasting legacy was his break with the national Democratic party: Shivers supported Eisenhower for president in 1952 and two years later refused to endorse the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark school desegregation case. Though Lyndon B. Johnson and the liberal wing of the party didn’t give up without a fight, the grapefruit governor did more than anyone to drive the wedge that would eventually turn Texas as ruby red as the fruit that paid his bills. (His son, Allan Shivers Jr., would one day serve on the board of Texans for Lawsuit Reform, the Republican fund-raising juggernaut that helped solidify Texas as a GOP stronghold forty years later.)

Shary’s empire notwithstanding, fortune hasn’t always smiled on the grapefruit industry in Texas. Brought here from Jamaica by way of Florida, most likely by Spanish missionaries, Citrus paradisi was never meant to grow in the Rio Grande Valley at all. The grapefruit’s ancestor, the pomelo, evolved in the Indian tropics, most likely the Malay Archipelago, though nobody knows for sure, because it has been widely cultivated in South Asia for at least a thousand years. Wherever it originated, you can be certain it was a place that never froze and got a lot more rain than the Valley, which enjoys only around 22 inches a year. It never freezes in the Valley either—except when it does. Texas citrus has never really recovered from the last two devastating freezes, in 1983 and 1989, which reduced total plantings from almost 70,000 acres down to roughly 27,000.

The truth is, there was too much grapefruit in the Valley in those days for growers to make much money anyway. Thanks in part to the grapefruit diet craze of the mid-seventies, when marketers assigned the fruit all kinds of qualities it did not have, including the tendency to make you want to eat less of everything else, growers had been on a planting binge. (The grapefruit diet was the Atkins of its day; by 1983, only oranges and apples were more popular at the average grocery store in New York.) Even if growers wanted to plant that much fruit again today, they couldn’t, at least not if they continue to use the Old Testament–era flood-irrigation techniques still employed on most Valley farms. The Rio Grande, source of all irrigation water in the region, doesn’t carry nearly as much water to South Texas at it did in the seventies. In the current drought, several Valley irrigation districts have simply run out of water for their customers.

The freezes of the eighties forced many smaller growers out of business. Most of those who remained used the massive losses following the 1983 freeze as an opportunity to replant entirely in Rio Red. (Grapefruit accounts for about 70 percent of the Texas citrus crop and virtually all of it is Rio Red.) Holbrook decided to do something even more radical: he began the first commercial organic citrus operation in the Valley. At the time, organic produce was a niche market that catered to hippies, but Holbrook, who worried about low profit margins for conventional grapefruit, thought it might offer a lifeline for his business. He was also motivated by a startling personal revelation. When a group of researchers from Texas Tech came to the Valley to study the occupational hazards of the citrus industry, he’d had his own body tested for pesticide residue. “I was off the charts,” he recalled. His fellow growers thought he was crazy, but Holbrook began weaning his operation off chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Growing his business in tandem with his first big customer, Whole Foods in Austin, he proved that citrus could be grown organically in Texas. Eventually Holbrook became one of the most respected figures in Valley agriculture.

When the citrus greening scare began, his expertise made him a natural choice to join a team of growers and researchers committed to finding biological—rather than chemical—methods of fighting the disease’s spread. The decision to look for solutions beyond traditional pest control wasn’t made just for health and environmental reasons. Even conventional growers understand that their current rate of spraying is financially unsustainable. By some estimates they are spending half their total overhead just on poison. Yet the psyllid is so potentially dangerous that any pause in control efforts could be devastating. With help from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and scientists at the Citrus Center—now a thriving, modern research facility run by Texas A&M—the team considered a variety of nonchemical anti-psyllid agents. One promising solution was a fungus known to prey on psyllid nymphs. “The idea was to spread it across the entire Valley from a plane,” Holbrook said. In the end, however, they decided instead to deploy a weapon that had wings of its own.

The plan began to take shape in August 2009, when Dan Flores, a USDA entomologist based in Edinburg, managed to procure a batch of Tamarixia radiata, a tiny wasp—about the size of a capital I on this page—that is the psyllid’s main predator. He had them delivered from Pakistan, carefully packed in Styrofoam coolers, by FedEx. He then set about breeding the wasps, by the hundreds of thousands, in insectaries of his own design: greenhouses filled with rows and rows of small, tented orange jasmine trees, each one infested with Asian citrus psyllids. By 2012 Flores’s army was ready to be deployed.

It was sent not to the groves themselves but to strategically selected neighborhoods across the Valley. Not all the region’s citrus is found in orchards, thanks to the peculiar land-use patterns in the Valley. Fifty years ago, the area was a sea of farmland surrounding a handful of small towns that stretched along U.S. Highway 83 like a string of islands. After trade with Mexico boomed in the nineties, however, subdivisions began to reach farther and farther into the citrus, onion, and cotton fields. As land became more valuable and agriculture more tenuous, one grower after another decided to cash out his holdings and pull up stakes. The result is that today much of the Valley resembles a curious patchwork: onion fields are found next to new elementary schools, citrus groves abruptly give way to neighborhoods of brick houses, which in turn fade back into citrus on the far side. Remnants of the old orchards are everywhere—in backyards, in strip-mall landscaping, even in the medians of highways—and every dooryard tree, as noncommercial citrus trees are called, is a potential host for psyllids, and thus for citrus greening. A grower can spray all he wants to in his fields, but psyllids from the neighborhood adjoining his land will simply move in once the poison is gone.

And since he can’t spray in the neighborhoods, he needs the wasps. Flores started in mostly “winter Texan”–filled RV parks built in razed orchards, where a few trees are usually left standing. So far, the strategy seems to be working, according to Mamoudou Setamou, an entomologist at the Citrus Center and the Valley’s resident expert on the Asian citrus psyllid. “We are seeing amazing parasitism rates on trees infested with psyllid nymphs,” he told me. The hope is that the wasps will multiply and spread, eventually driving psyllid numbers low enough that growers can begin spraying less often. Setamou came to the Valley from Benin, in West Africa, by way of Germany, where he received his Ph.D. (The Citrus Center, housed in a handsome new building erected in 2010, is a veritable United Nations of research. On one afternoon, in addition to Setamou, I met a molecular biologist from Brazil, a plant physiologist from Spain, and the center’s director, John da Graca, a virologist from South Africa.)

In September Setamou gave me a tour of his lab, where he had a small Tamarixia breeding operation under way in a few tented trees. He spotted a fugitive psyllid clinging to the outside of the white gauzy fabric of one of the tents. He reached out and snuffed it out with his finger. It was a mercy killing compared to what was going on inside the tents. When a wasp attacks a psyllid, death does not come swiftly. First the wasp stings the psyllid, paralyzing it, and then lays an egg under its hapless victim. When the egg hatches, the larva eats its way into the still-living psyllid, consuming it from the inside out. Eventually, an adult wasp emerges from the dead husk (researchers call them mummies) and flies away to kill again. After seeing Tamarixia radiata at work, it wasn’t hard to understand why the psyllids wanted to leave South Asia.

To enter a Valley orchard today is to enter a war zone in miniature, though it is a conflict you could miss entirely if you don’t know where to look. Under any leaf the grower’s deadly proxy might be attacking his mindless, avaricious nemesis. But the psyllid is not without its allies. Like aphids, psyllids produce a sweet, nutrient-rich excretion called honeydew, which is manna to ants of all varieties. Ants are so fixated on the psyllids’ honeydew that even though the plants in Dan Flores’s insectaries are enclosed in greenhouses and individually tented, he has to set them in trays filled with water—little moats—to keep the ants out. “We see them just waiting. Like a story from the Bible, just sitting there waiting,” Flores said. If the ants get access to the plants, they will fight off the wasps to protect the psyllids, like sheep ranchers shooting at hungry coyotes. Flores has seen them building bridges with their own bodies to cross the moats and picking up and hauling off parasitized psyllids before the adult wasps can emerge and find more victims.

Setamou was not particularly philosophical about the conflict he had helped instigate or the tiny tortures visited upon his enemies. “It is a war, and we are forced to choose sides,” he said. “Our future depends on it.”

The idea that one of God’s creations might save the Texas grapefruit where synthetic poisons have failed has an undeniable appeal. In H.G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, humans were no match for the invading martians: “After all man’s devices had failed,” Wells wrote, the invaders were brought down, finally, by our bacteria, “the humblest things that God, in his wisdom, has put upon this Earth.” As biological weapons go, beneficial predators are a little more problematic than everyday germs. They are more like the Cold War–era bombers the Air Force once kept constantly deployed on the edge of Russian airspace: once the decision is made to send them to their targets, you can’t call them back. A voracious new predator spread throughout an unsuspecting ecosystem—what could go wrong? Setamou assured me that his wasps prey only on Asian citrus psyllids, not on, say, honeybees or any other beneficial insect. To be certain of this, Flores offered the wasps a variety of alternative prey species over an extended study period in his insectaries, but they declined them all. They don’t sting people either.

“What if they were to eat all the invaders,” I asked. “What would they turn to then?”

“Realistically, that will never happen,” Setamou said. But while the wasp project has moved forward at a cautious and deliberate pace, it’s not hard to imagine a similar conversation between commercial fish farmers and regulators in the seventies, when Asian carp were imported to help keep catfish breeding ponds clean in a couple of Southern states. These amazingly adaptable fish have since traveled up the Mississippi almost to the Great Lakes, crowding out native species up and down the length of the basin in an ongoing ecological disaster.

If you spend some time in the Valley, however, such concerns may begin to feel a little naive. Thinking about today’s Valley as an ecosystem, one hundred years after John Shary established his first orchards, doesn’t make much sense. The Valley—planted corner to corner in onions, melons, citrus, and cotton—is something more akin to a factory, a four-thousand-square-mile open-air shop floor as engineered as any Toyota plant and just as dedicated to the production of value. Does the auto plant manager care whether his parts are made in Asia or North America? A bolt is a bolt, and a bug is a bug, and it has been this way for a long time. American farmers have long deployed beneficial insects—many of them imported from far-flung locales—to fight pests. (Another popular beneficial in the Valley is the mealybug destroyer, an Australian cousin of the ladybug that was first imported by California farmers in 1891.) The wasps aren’t supposed to be here, but neither are the psyllids. Or, for that matter, the grapefruit groves themselves.

If you want a glimpse of what the Valley looked like when it actually was an intact ecosystem, you can visit the Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge, which sits along the southernmost bend of the Rio Grande, about ten miles southeast of McAllen. There you will find two thousand virgin acres of moss-hung oaks, giant sabal palms, and thick, buggy brush, complete with artificial oxbow lakes of the kind the Rio Grande used to leave behind after periodic floods in the days before the upstream dams were built. The refuge, part of the 5 percent or so of the Valley that remains undeveloped, is home to a handful of ocelots and a bevy of tropical birds at the northernmost point of ranges that stretch down into Central America. Walking through the cacophonous woods, you could be in Nicaragua, until you climb the observation tower and get a glimpse of the produce trucks churning along U.S. 281. If the trucks are not in evidence on your visit, a Plexiglas-ensconced satellite photo is mounted helpfully on the railing to remind you that the primordial canopy you see below is but a single pinprick of entropy in a vast, checkered tapestry of painstakingly plowed progress.

Because citrus greening is a disease with a long latency period, it is far too soon to tell how bad the outbreak in the Valley may yet become. Most of the roughly one hundred infected trees identified so far were found in groves in San Juan, inside the area quarantined after the first such discovery back in January 2012. Officials were obliged to create another quarantine zone in September of this year, however, when a stricken tree was discovered in the yard of a house in downtown Mission. Psyllid numbers seem to be under control, at least for now. Yet Citrus Center researchers have collected a few psyllids bearing the disease in locations ominously far from the quarantined zones.

Several growers I spoke with were encouraged by another recent development in the Texas citrus business. Last year a California-based company called Paramount Citrus bought the two largest packing operations in the Valley, along with more than half of all the citrus acreage. Paramount is a division of Roll Global, an agribusiness giant that once billed itself as “the largest privately held company you’ve never heard of.” The company is owned by Beverly Hills billionaires Lynda and Stewart Resnick, the marketing savants behind the Cutie line of mandarin oranges that suddenly appeared in every child’s lunch box in America a few years ago and made growers in California’s San Joaquin Valley a lot of money. Paramount is installing new, state-of-the-art drip-irrigation systems in its Texas groves and building an enormous cold-storage facility, big enough to serve as a distribution hub for its citrus operations not only in the Valley but in Mexico as well.

Some Valley growers see Paramount’s huge investment as a vote of confidence—a bet, in essence, that greening can be beaten in Texas. When I asked Paramount president David Krause about greening, he was a little less sanguine. “We intend to fight it in every way possible, but as of today it’s a scary thing,” he said. “We don’t have a solution. But we are a well-capitalized business that believes that there will be a solution at some point in time and that we’ll survive long enough to be able to see that.”

That’s a new kind of thinking in the Valley, and it comes with a new language too. Krause, who is based in Delano, California, where Paramount operates the world’s largest citrus-packing plant, uses terms like “product mix” and “customer base” and “portfolio,” often all in the same sentence. For years, growers in the Valley have marketed their produce collectively, spending about a million dollars a year. Paramount recently announced a new marketing campaign for the next generation of small, easily peelable mandarins, which they are calling Halos. The budget is $100 million. The idea that the Resnicks could do for Texas grapefruit what they did for California mandarins has the Valley buzzing. But the possibility that they might also do for smaller growers what Walmart did for downtown merchants hasn’t been lost on the locals either. Then there is a third scenario, the one where everybody, newcomers and old-timers alike, loses everything to a tiny brown bug from Asia.

John Lackey, who chairs Texas Citrus Mutual, sees Paramount’s arrival as a good thing. “More marketing, more production means more for everybody. We’ll be able to ride the wake,” he said. As it happens, Lackey recently sold off most of his own acreage, except for a small grove near his home, which he has planted in limes (organic, so he wouldn’t be spraying pesticide so close to his own family). In recent years his grapefruit trees stopped producing like they used to, he said, perhaps because the soil was simply worn-out. Lackey now runs a wealth management company located in a Weslaco strip mall. Some of his clients are growers, but these days more wealth is being generated in land development and the manufacturing industry, which has boomed since the passage of NAFTA twenty years ago. I wanted to talk to him about what it would mean for the Valley now that a majority of the citrus was owned by a company located somewhere else, funneling money that used to be earned and spent here to bank accounts in Beverly Hills. Somehow we wound up talking instead about what his generation of growers has brought to the Valley. He was surprisingly candid. “We have not created enough of the kind of jobs that keep kids here after college,” he said. “We have a largely unskilled, uneducated workforce, a lot of people living off the government.”

In fact, compared to when Lackey was a boy, a much larger percentage of Valley residents complete high school. The problem for growers is that nobody with a high school diploma wants to pick citrus, or onions, or melons. “We want our own people to rise up and do better,” Lackey said, even if it undermines one of the Valley’s economic mainstays. But that means growers have to rely on a steady flow of unskilled immigrant labor. Even the maquiladora industry, notorious for its low wages, is a threat to the economic model that has prevailed in the Valley since John Shary’s day. The bottom line is that commercial agriculture depends on a reliable stream of people who simply can’t find any better way to feed themselves than to spend all day stooping, reaching, and filling boxes in the hot sun for $8 an hour.

It also depends on the continued supply of a dwindling resource. Growers are accustomed to an abundance of cheap water; they pay around $26 an acre-foot here, a fraction of the cost in California, and they currently monopolize 90 percent of all the water used in the Valley. If the population continues to increase at the rate it has, growers could find themselves paying more or could even see their allotments curtailed in favor of municipal and manufacturing customers. In fact, there is a palpable sense in the Valley that the old way of life is dying. In the eighties and nineties competition from out-of-state growers and higher costs forced consolidation, not just in citrus but in almost every sector. Rail lines in towns like Weslaco are lined these days with empty and decrepit packing sheds. The Valley even smells different now, Lackey said. “You should have been here when we had seventy thousand acres of citrus blooming at once,” he said, shaking his head. “The whole Valley smelled like flowers.”

“I love what I do,” Dennis Holbrook told me toward the end of our tour of his orchards. “I love the whole process of preparing a piece of land, planting the seed, nurturing it, seeing it grow and eventually produce.” Holbrook has friends who have plowed under their groves and gone into land development, in some cases earning millions. As long as the Valley continues to boom, he knows he could do the same. He knows also that his future in citrus is uncertain. “Look, I’m a fifth-generation farmer. It’s just hard for me to knock that dirt off my boots and forget about it. It’s ingrained in me.” He stopped his truck alongside a row of Rio Reds and pulled his cellphone out of his pocket. “Let me show you something,” he said, with a conspiratorial grin. I felt like I was about to get a stock tip. He showed me instead a photo of a grapefruit tree, festooned with plump fruit. I didn’t see anything unusual until Holbrook urged me to look closer. “The color,” he said. The blush on the skin was redder than any variety I had ever seen. Redder, in fact, than anybody has ever seen, which was the source of Holbrook’s excitement. I was looking at the next big thing in Texas grapefruit, an ultra-red, ultra-sweet mutant discovered in one of the Citrus Center’s experimental groves about ten years ago. It was nothing less than a promising new strain, a carefully guarded, patented variety—tentatively called the Texas Red—that researchers have been developing ever since. It was still years away from being ready for commercial use, a project known at this stage only to citrus insiders. Holbrook couldn’t tell me exactly where the trees were, since he didn’t know himself. “They might blindfold you and take you out there,” he said.

It’s hard to keep a secret for ten years, of course, and the Citrus Center has been fielding regular inquiries from abroad. Growers in Turkey think it would be a hit in Russia and on the European market. There is interest in South Africa too. But Valley farmers get the right of first refusal, since they fund the research at the Citrus Center. And the truth is that our state fruit, like many Texas exports, just seems to shine brightest when it is closest to home. The red grapefruit grown in Florida and California is descended from the same sports discovered in Valley orchards eighty years ago, yet by all accounts our fruit is consistently better. Something about the combination of the soil and the climate makes the Valley grow beautiful grapefruit, even though it shouldn’t. If the wasps thrive, it may continue to do so, at least until the next calamity strikes.