This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

As recently as a hundred years ago, log buildings were so plentiful that they dominated the landscape of most of the eastern half of Texas. Our ancestors lived in log houses, stored their food and feed in log cribs and barns, sheltered their horses in log stables, and prepared their meals in log cookhouses. When they traveled, they found overnight lodging at log inns; if they had business to transact or purchases to make, they did so in log stores, trading posts, and offices; if they had legal duties or difficulties, they went to the log courthouse or were escorted to the log jail. Those in need of spiritual comfort sought it in a log chapel; others, preferring the company of demon rum, drank it at a log tavern. Men and women who had learned to read and cipher acquired these skills in a log school. Interestingly, schoolhouses apparently ranked low in priority in frontier Texas. One early Fannin County temple of learning was a log stable, converted into a school simply by being “thoroughly cleaned.” Another, in Travis County, had a raised doorway, in order “to prevent the ingress of pigs.”

Our ancestors took more care in the construction of jails than schools, possibly because there were more outlaws than children. A typical Texas log jail had double walls, often with stones or vertical beams inserted between them and square nails placed every few inches to prevent saw-outs. Denton’s log pokey had no door or windows; prisoners entered through the ceiling. To spend a July day incarcerated at Denton must have been a memorable experience.

Many early visitors to Texas recorded their impressions, often unfavorable, of the overwhelming presence of log buildings. Mary Eubank, whose first view of Texas in 1853 was of the Bowie County hamlet of DeKalb, referred to it as “a small place called Decab . . . but I think Decabin the most appropriate name.” Other travelers reported that Brazoria in early days “contained about thirty houses, all of logs except three of brick and two or three framed,” and the infant Dallas consisted of “two log cabins, the logs just as nature formed them.”

To a remarkable degree, log architecture cut across ethnic and class borders in nineteenth-century Texas. Southern Anglo-Americans, blacks, Germans, Alabama-Coushatta Indians, Alsatians, Scandinavians, Irish, and Slavs lived in log buildings. Rich and poor, planter and slave alike called them home. But while the basic construction was the same, the rich man’s log house was taller, larger, and better crafted than his poorer neighbor’s. The range was from grand two-story log plantation houses built of neatly hewn timbers carefully dovetailed together at the corners and covered with milled siding to humble one-room backwoods cabins consisting of bark-covered logs fastened by crude saddle notches. Then, too, each ethnic group placed a distinctive mark on its log architecture. It is possible to distinguish among the houses of immigrant Appalachian hillsmen, coastal plains Crackers, Europeans, blacks, and Indians by the way they are built. Floor plans, corner notching, and other details of construction tell much about migration and local ancestry.

Other than the ethnic origin of the builders, one of the strongest influences on log architecture was the physical environment. In East Texas, where trees are plentiful, log buildings are—or were—abundant. But in West Texas, where trees are practically on the endangered list (there is actually a town near Odessa named Notrees), there is only a smattering of log buildings. Rooms in cabins outside East Texas are rather small. In west central Texas, rooms measured no more than twelve or thirteen feet on a side, in contrast to sixteen to twenty feet in the pine forests of East Texas.

Even so, the tradition of living in wood houses hung on tenaciously as settlers moved west across Texas. On the Great Plains, pioneers sometimes hauled timbers many miles to a construction site. One enterprising settler in a treeless Panhandle county, determined to have a log house, stole timbers from a railroad trestle under construction over the Canadian River. A few nights of such pilferage provided him with materials for a comfortable dwelling.

Most frontier settlers were not lucky enough to acquire their houses free of charge. Although crudely built cabins were the work of volunteer amateur labor at festive house raisings, professional carpenters charged for building the better-crafted homes. The price of a log house in northeastern Texas around 1850 ranged from $20 to $75. The $20 version was a plain log hut, eighteen feet square, with a rough wooden floor, built by two men in two days; the $75 version was a two-room house of hewn pine logs requiring three men three days to finish. Hired carpenters also built log courthouses, using specifications set by county commissioners. Around the mid-1800s, Cooke County obtained a small, dirt-floored, chimneyless cabin courthouse for $29, while Ellis County citizens displayed a bit more civic pride with their $59 model. Panola County taxpayers purchased what must have been a log palace for $200. No matter how much they cost, log buildings were often less stable than they looked. The first Cooke County Courthouse came to an abrupt and inglorious end about 1855, when a fly-crazed steer charged inside. In making an equally hasty egress, the panicked beast ran against one corner of the log building and brought it tumbling down.

Beyond the availability of money and trees, the climate also influenced the range of log architectural styles that can be found throughout Texas. Each district boasts a distinctive type. In humid, subtropical East Texas, for example, an open “dogtrot” separates the house into two parts and provides a place for the occupants to eat and rest during the heat of the day. Breezeways are less popular in North Texas, where winter northers turn dogtrots into frigid wind tunnels.

Most log buildings in the state date from the nineteenth century. In the 1870s, log farmhouses probably accounted for well over 50 per cent of all occupied rural dwellings in Texas. In the 1930s, the number had dwindled to only 1 per cent, most of them located in the Big Thicket counties such as Polk and Orange, in the Piney Woods counties such as Bowie, in Cooke and other Cross Timbers counties, and in the wooded Hill Country of Central Texas. Today I estimate that there are no more than six or seven hundred occupied log houses in the state, excluding those used only as hunting cabins or retreats. But such an estimate is tentative at best. Some people are unaware that the home they occupy has a log core, so skillfully and so early was the siding applied.

There is at present quite a boom in restoring historic log buildings and in erecting pre-cut new ones as weekend cottages, but very few log structures have been built since 1945 using traditional construction methods—aside from a few amateurish Boy Scout Modern specimens.

Why did a construction technique once prevalent fall so rapidly from favor? Mainly because of social stigma. Log houses were symbols of the frontier, of backwardness, deprivation; signs of personal failure to be occupied with shame by those who did not succeed in our competitive economy. Status could be gained by discarding the log house and replacing it with one of frame, brick, or stone. At the very least, upwardly mobile folk were expected to conceal the logs with milled siding. Even as early as 1826, founding father Stephen F. Austin bore with resignation his log cross, confessing that “we still live in log cabins.” Jacksonian democracy made it socially acceptable for a presidential candidate to have been born in a log cabin, but it was definitely not fitting for the candidate to continue living in one. Lyndon Baines Johnson wished, and in weak moments even claimed, that he had been born in his grandfather’s log house in Johnson City—a house far more elegant than his actual frame birthplace—but I never heard that he expressed a desire to live there.

To conceal their shame, some misguided log-house dwellers tacked artificial brick siding onto the exterior walls. One who did not is a friend of mine—an elderly woman of Indian Creek community in Cooke County, in the heart of East Cross Timbers. She was born and raised in her fine dovetailed log house eight decades ago, and she has never lived anywhere else. When I first met her in the early seventies, she was stoically enduring her nonelectric, rough-hewn dwelling as a badge of spinsterhood. “If I had a’married, I’d not have to live in a house like this,” she maintained. If this woman’s attitude has changed since I first visited her home, it is probably because I have brought five hundred or so of my students to look at, admire, measure, and photograph the structure. I suspect, instead, that she regards me and my students as slightly demented.

Today there is a new respect for log buildings. Even though we citizens of modern, urban Texas have little in common culturally with our rural ancestors and their log buildings, we do find folk architecture appealing. Perhaps we are nostalgic for a past most of us never knew—a time before we made the momentous, irreversible, and possibly fatal decision to abandon historic ways and follow the broad path of industrialization. In any case, eleventh-hour efforts to rescue log buildings appear at every turn.

Several major kinds of restoration result from these efforts. In one type, preservationists drag log houses off to zoolike compounds to stand empty and unused, protected from vandals by unsightly chain link fences and shielded from visitors by ropes blocking the doorways. The town of San Saba offers the ultimate in this type of restoration: a single cedar log dwelling in Mill Pond Park imprisoned by a chain link fence erected not more than several paces from the house walls.

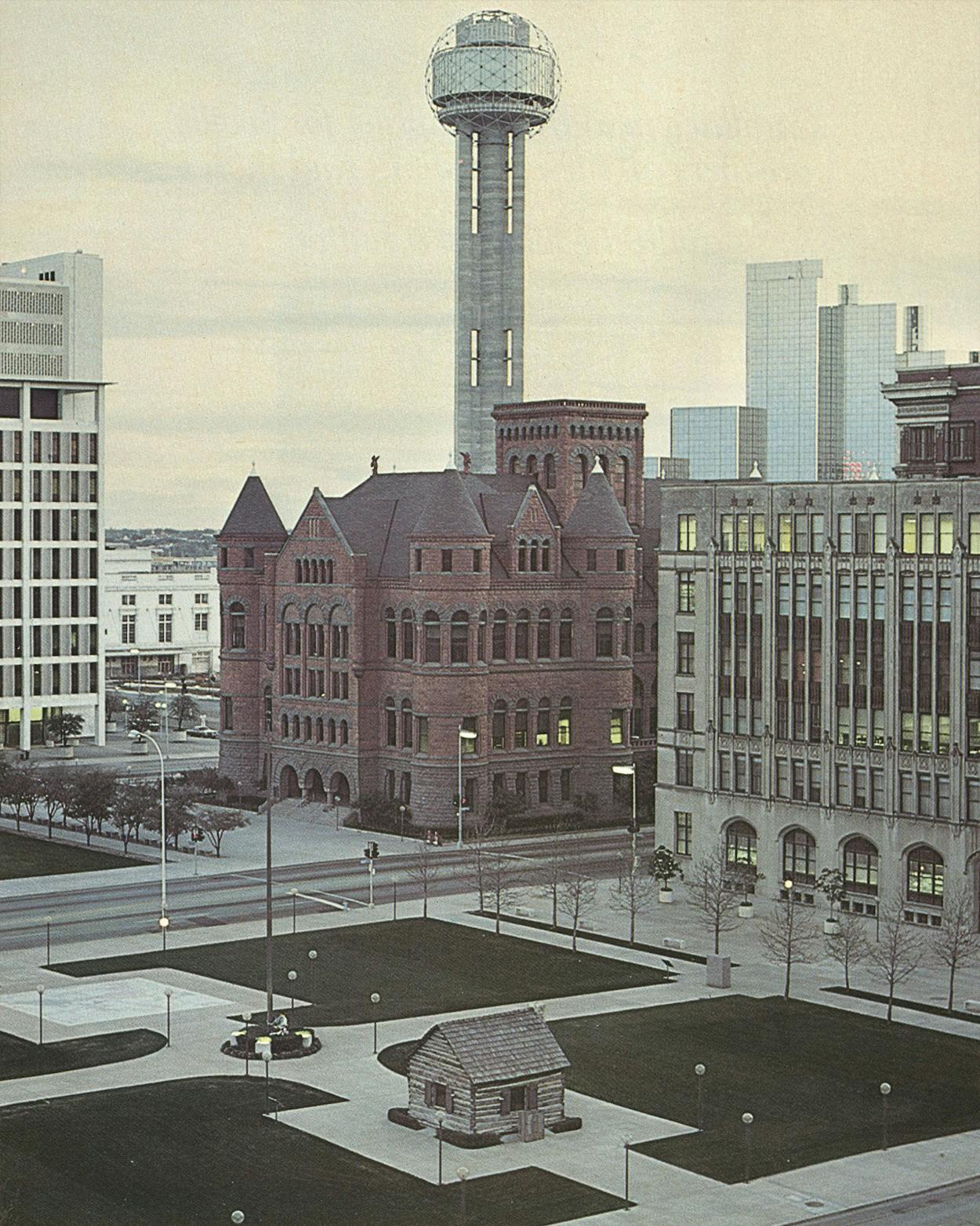

In some other instances, the rescued cabin is prominently displayed in a public square, as if the city fathers mean to say, “See how far we have risen from our humble beginnings.” One of the most pathetic sights in Texas is the John Neely Bryan log cabin in downtown Dallas. Flanked by cropped nursery shrubs and drowned in manicured putting-green lawns and concrete sidewalks, the Bryan cabin looks out self-consciously on a huge red sandstone Victorian courthouse and a futuristic monument to a slain president. The little house cries out for trees and privacy or at least compatible architecture. I know of only one worse example—the Lincoln birthplace cabin. Honest Abe’s first home stands inside a pillared Greco-Roman temple atop a Kentucky hill, at about the sacred spot where one would expect a buxom statue of Athena or Aphrodite. The exterior approach is a grand stairway which, according to cultural geographer Peirce Lewis, would “do credit to Benito Mussolini.”

The really big restoration boom, though, is in weekend cottages. People from Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, and other cities have descended upon surrounding rural areas like locusts, devouring every log house in sight. They restore them with widely varying degrees of accuracy, usually adding plumbing and air conditioning, as hunting cabins, weekend homes, or conversation pieces. One I know of in the Big Thicket was furnished to look like a whorehouse—a sort of early-day Chicken Ranch.

Farmers quickly responded to the new demand. For two generations they had unthinkingly consumed log houses as cords of well-seasoned firewood or ready-made fenceposts. Initially, when the city slickers appeared on their front porches, cash in hand, asking to buy and remove grandpa’s decaying log house, the farmers were only too glad to sell for a hundred dollars or so. But with a peasant cunning aroused by increasing demand, they soon jacked up the price. Farm folk started to haggle about money, feign disinterest, exhibit false pride in the structure, and seek professional appraisals. I personally watched a very wealthy Dallas businessman meet his match in one such contest. Insult was added to injury when a resident mongrel, without warning or provocation, bit the man on the leg, drawing blood through the leg of his nicely tailored suit.

I have five or ten letters in my correspondence from rural people asking me to estimate the cash value of their log structures. This I have done free of charge, in exchange for photos and measurements of the structures. They are usually grateful. “With the information you recently supplied us on the value of our log cabin,” wrote a rural inhabitant of the Houston hinterland, “we have negotiated a sale.” Recently a prominent Washington-based Texas politician seeking to buy a log house was quoted a price of $5000. Obviously, log buildings have ascended to the status of antiques. For those unwilling to search for and purchase authentic cabins, a variety of prefabricated, milled log models are now on the market.

What will happen to the few remaining authentic log buildings? Botched restorations aside, a high toll of log structures is claimed annually by vandals, grass fires, bulldozers, dam builders, and neglect. The last generation of authentic log-house dwellers is now aged. By the end of this century few, if any, occupied log houses and functional log outbuildings will remain, and a tangible tie to the frontier era in Texas will have been severed.

Terry G. Jordan is a cultural geographer at North Texas State University in Denton. His latest book, Texas Log Buildings: A Folk Architecture, was published this year by the University of Texas Press.

- More About:

- Style & Design

- TM Classics

- Architecture