The rivalry between Houston and Dallas seems as old as Texas itself, with residents arguing about which city has the better sports teams, restaurants, and culture. (Having lived in Dallas for, well, forever, I’m pretty confident about my answers.) But there’s one arena where Houston’s bragging rights have been unquestioned for decades: the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, which is world famous for its level of treatment and research.

Now Dallas is fighting back, and it’s about to drop the proton bomb. Both Baylor Health Care System and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have plans to open cutting-edge proton therapy centers, which will use an intense form of radiation treatment that can strike malignant cells more accurately than traditional radiation while protecting healthy tissue nearby. But the facilities don’t come cheap. Each one will cost more than $100 million. Currently, the only hospital in the state that has one is—you guessed it—M.D. Anderson.

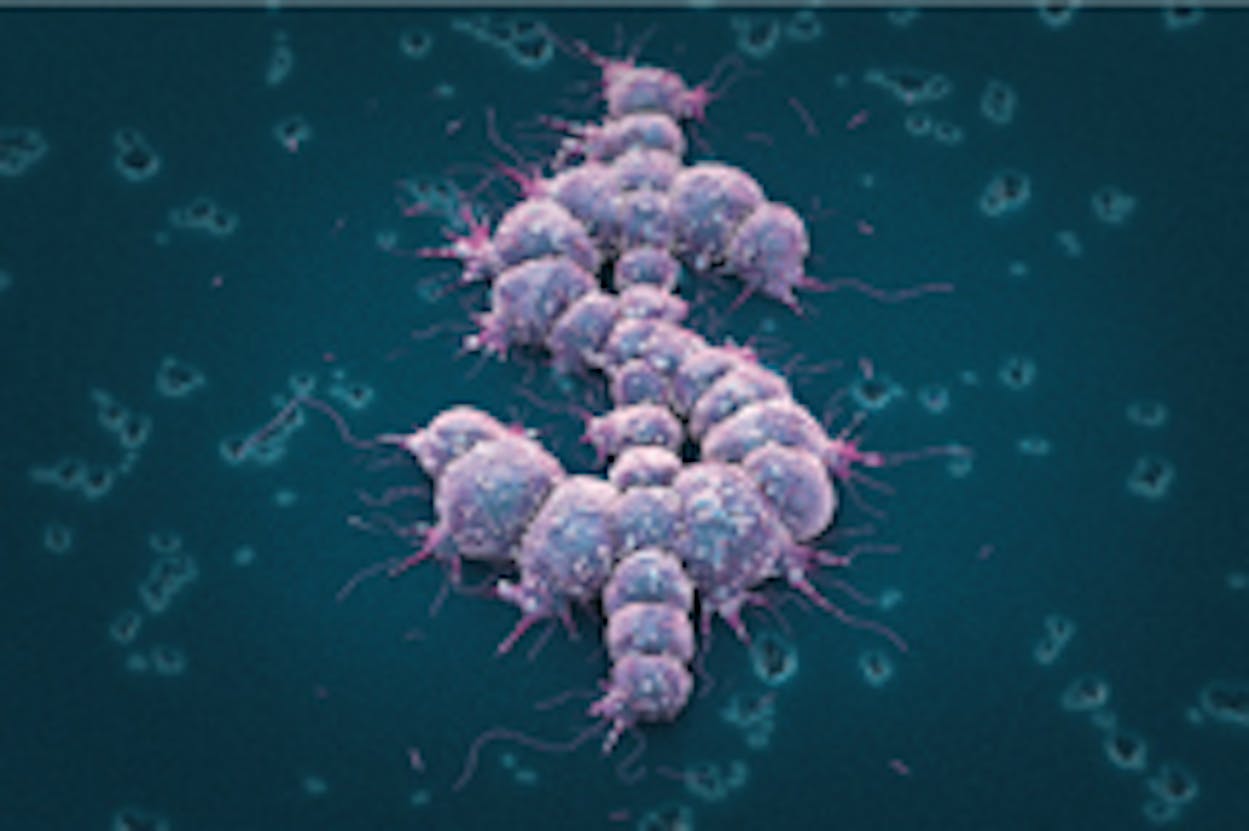

Cancer treatment, of course, is the work of angels—doctors, nurses, and researchers who are dedicated to curing the dreaded disease or keeping it at bay. Cancer will strike an estimated 110,000 Texans this year, according to the Department of State Health Services, more than the entire population of Tyler. But as seen with the proton therapy centers, those numbers are also driving an arms race between hospitals, which realize that cancer care, for all its life-or-death importance, is an increasingly lucrative business.

Direct cancer costs in Texas last year were estimated at nearly $13 billion, up from about $10 billion in 2007. And the numbers will continue to rise as the state’s population grows and ages. Cancer is most likely to be diagnosed in the senior years, and Medicare or private insurance typically covers the treatment, making the potential for profits impressive. Adding to the competition is a commitment by the state to invest heavily in cancer research. In 2007, at the urging of Lance Armstrong, Texas’s most famous cancer survivor, voters authorized the state to dole out up to $300 million a year for research.

It’s no wonder, then, that Baylor and UT Southwestern are pouring money into their facilities in an effort to attract new patients. In January Baylor opened a $375 million cancer hospital and outpatient center. In the outpatient center, patients are assigned personal advisers who help schedule doctors’ appointments and offer nutritional advice. Patients also can attend cooking classes or work out in a fitness facility. In the hospital, which has been opening two floors at a time, rooms have foldout couches, refrigerators, wireless Internet, and dual televisions to better accommodate family members and other visitors.

UT Southwestern has spent $33 million over the past two years to upgrade its facilities, and Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons has pledged more than $100 million. Beyond the money, UT Southwestern boasts that it’s the only hospital in town with a National Cancer Institute designation, which allows it to access certain NCI grants and treatments still under development. The hospital is now setting its sights on the next step: to become an NCI comprehensive cancer center, which will open up an even higher level of potential funding sources. (The only center in Texas at that level is, not surprisingly, M.D. Anderson.) Though smaller than M.D. Anderson and Baylor, UT Southwestern has made impressive strides: cancer treatment now accounts for about a third of its patients and its research dollars.

Still, Baylor and UT Southwestern lag far behind M.D. Anderson. Founded in the forties, the hospital has established itself as one of the world’s top cancer centers, drawing such famous patients as rocker Eddie Van Halen and writer Christopher Hitchens. But it is also in the process of rapid expansion. Over the past five years, M.D. Anderson has increased its office, treatment, and research space by 50 percent and is spending $272 million to add floors to its Albert B. and Margaret M. Alkek Hospital. “The more we build to serve a large group of patients, the more we see,” says Dan Fontaine, M.D. Anderson’s senior vice president for business affairs.

Last year the center treated 34,000 new patients, up 17 percent from 2007, with only a third of those patients coming from the Houston area (much to Baylor’s and UT Southwestern’s chagrin, M.D. Anderson admitted 3,400 patients from the Metroplex last year). Over the same time period, while the financial crisis set many businesses back, M.D. Anderson’s revenue soared to $3.66 billion, a 27 percent gain since 2007. About three quarters of that came from patient care, with the rest mostly from grants, gifts, state subsidies, and investment income. After costs, M.D. Anderson reported a whopping income of $606 million, almost double the amount it made five years ago.

The hospital also has benefited from the state cancer agency, the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT). M.D. Anderson has received $128 million from CPRIT, second only to UT Southwestern, which has gotten $173 million. (That tally doesn’t include a joint $20 million grant to M.D. Anderson and Rice University, which caused an outcry this spring when CPRIT’s chief scientific officer resigned after protesting that the grant didn’t undergo a proper scientific review. Amid the allegations, M.D. Anderson agreed to resubmit the proposal, and the agency said it would subject it to a more rigorous review.)

The arms race may have an unexpected cost, however. Baylor is teaming up with McKesson Specialty Health and Texas Oncology, a regional network of more than three hundred doctors, and expects to break ground this year on its proton therapy center, which will cost more than $100 million by the time it opens in 2015. UT Southwestern, meanwhile, has signed a letter of intent to operate a $220 million center that San Diego–based Advanced Particle Therapy LLC plans to build by 2016, pending approval by the UT Board of Regents.

But given the price tags, are these centers cost effective? Studies have found that proton therapy is particularly useful for pediatric cancers and cancers of the head, neck, and spine. Altogether, however, those cancers are relatively rare. Ideally, the technology could be used to treat prostate cancer, which is far more common. But research has found that traditional radiation treatments for prostate cancer are just as effective as proton therapy, with similar side effects. And a course of proton therapy can cost almost $50,000 compared with about $20,000 for traditional radiation. That means the new technology could drive up medical costs, at least in the short term.

Baylor and UT Southwestern talked about working together to build one center, but the two couldn’t resolve their differences. Robert Timmerman, a professor of radiation oncology at UT Southwestern, acknowledges that the technology comes with question marks but believes that researchers will find innovative ways to use it to treat the most pervasive form of organ cancer: lung cancer. If proton therapy can treat that, patients might require fewer treatments, which would ultimately bring costs down.

Even so, while choice and competition are generally good for patients, Dallas really doesn’t need two proton therapy centers. They could both cure cancer, but the one-upmanship could also end up costing everyone more in health care bills.