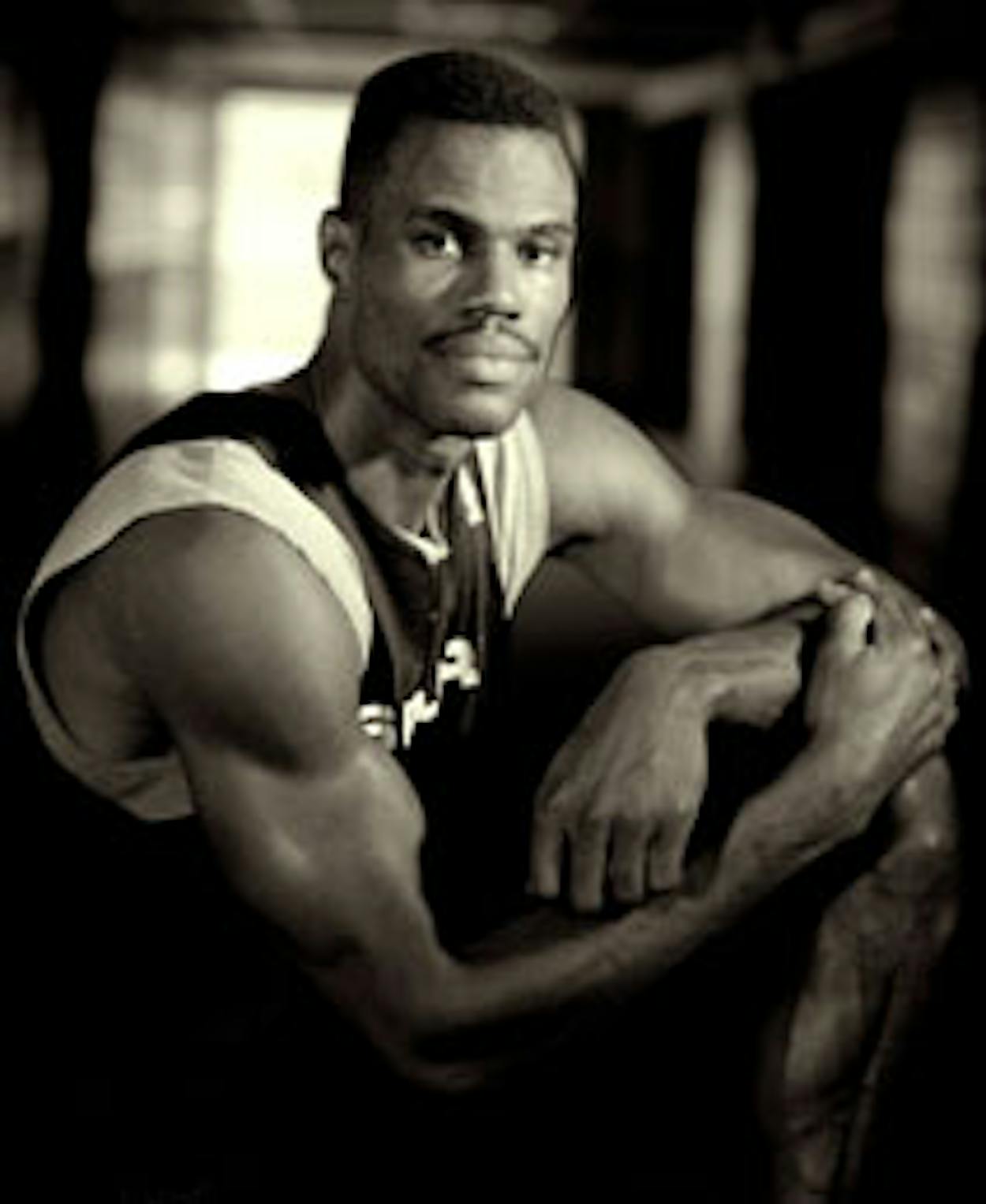

TOWARD THE END OF A TWO-AND-A-HALF-HOUR PRACTICE, David Robinson was loose and animated. The 36-year-old center for the San Antonio Spurs stutter-stepped toward the free throw line, took a pass from a coach, and fired off a fifteen-foot jump shot. He grimaced as the ball bounced high off the front of the rim, then repeated the drill and let another shot fly. The ball, however, continued its independent streak, this time hitting the rim once, then twice, before falling to the floor. Robinson, more playful than serious, swung his arm in frustration and let loose with the s-word. Well, it wasn’t that s-word. You would have had to cover your kids’ ears only if you didn’t want them to hear “Oh, snippy.”

When I asked him about that curious word choice later in the day, he threw back his head and laughed. “I’m surprised that you picked that up,” he said. “I’m trying to substitute some words. I don’t like to curse, but I’ve still got some of that left in me from my Navy days.” His explanation was as unnecessary as Tom Landry apologizing for excessive celebration on the sidelines. But the answer was vintage Robinson, who has filled the role of the NBA’s gentleman star for the past twelve seasons. His clean-cut image has remained intact since he arrived in San Antonio in 1989: the math major from the Naval Academy, the lover of classical music, the devout reader of the Bible, the consummate family man. In a league that some people associate more with thugs than role models, Robinson seems as likely as Laura Bush to sport a barbed-wire tattoo on his biceps.

Of course, the reputation has cut both ways. His critics say that he is too nice and that, as a result, he lacks both heart and intensity. Though he was the Spurs’ indisputable star from his rookie year until 1997, when the team drafted Tim Duncan in the first round, the “soft” label has always dogged him. Earlier this year Charles P. Pierce, a writer-at-large for Esquire, listed his five favorite big men in the NBA, a group that did not include Robinson. Though it was not surprising that he picked Duncan—the 25-year-old may well be the best player in the NBA this year—Pierce couldn’t resist taking a swipe at the Admiral in the process. He wrote that “Duncan’s mere arrival was enough to transform the San Antonio Spurs—and the underachieving David Robinson—into an NBA champion in 1999.” Measuring success solely on winning the title, Pierce overlooked the long road Robinson had taken while failing to live up to expectations. He earned rookie of the year in 1990, a rebounding title in 1991, defensive player of the year in 1992, the NBA scoring title in 1994, and league MVP in 1995. I could go on, but I can’t change the meaning of “underachieving” for people who should know better.

It should come as no surprise to Robinson’s detractors that this summer he was out underachieving again, proving that, off the court at least, being soft is part of his true greatness. On September 17 a private school called the Carver Academy opened its doors on the East Side of San Antonio. The campus, which is adjacent to the Carver Community Cultural Center, was Robinson’s gift to the impoverished neighborhood. He and his wife, Valerie, donated $5 million to make it happen. “We talked about this project for three years,” Robinson said excitedly, “and on the first day, sixty kids came here. It’s such an incredible feeling. Their lives are going to change because of this.”

The school is as tidy and inviting as the area around it is not. Across the street are empty lots and run-down dry cleaners and machine shops. To the east is an abandoned Friedrich Refrigerator factory that was being used as a haunted house. For now, even the academy is part construction site. When the school opened, only the administration building and the classrooms for prekindergarten through second grade were ready. The library, cafeteria, and science and technology labs are expected to open in December. The exteriors of the buildings for grades three through eight are also scheduled to be completed that same month, but the interiors of those classrooms, as well as the construction of the athletic center, gymnasium, and soccer field, depend on future fundraising. The students don’t seem to mind the work in progress. They have decorated a chain-link fence that surrounds one construction area with red, white, and blue plastic cups to make a U.S. flag and a heart.

After a quick shower that day at practice, Robinson emerged from the locker room wearing a pullover jersey that said “Navy” on the front, green shorts that came to his knees, and size-seventeen Nikes with “Jordan” printed on both heels. The start of the season may have been less than two weeks away, but what he wanted to talk about was education. As we drove toward downtown in his Chevy Avalanche, he explained how he had decided to start the school. He and Valerie are no strangers to charitable giving. They founded the David Robinson Foundation in 1992 to help people in San Antonio. “We wanted to do what Jesus did: meet needs,” he said. “If people need food, give food. If people need clothes, give clothes. But after a few years of that, Valerie and I felt like we wanted to do something that would continue giving after we were long gone.”

Robinson was giddy as he gave me a tour of the campus, greeting students with a booming “Good afternoon” and hugging the staff and faculty. Everything inside the school sparkles, from the windows to the drinking fountains. The campus surrounds a courtyard and a garden, and the classrooms are connected to one another by covered walkways. As Robinson crouched down to fit himself through the doorway of the first-grade classroom, the students were counting to five in Spanish. They all took enormous breaths when they saw him, and the room fell into dead silence. Wearing blue knit shirts, they stood, bowed, and changing languages, said, “Konnichi wa.” Robinson beamed at them, and one little girl couldn’t stop herself from blurting out, “David, I saw you on television last night.” “You did?” he asked, still grinning. “What was I doing?” As if on cue, all of the kids exclaimed, “You were playing basketball!” He giggled, then thanked them for letting him interrupt their lesson. As he turned to leave, the kids said good-bye with a thundering shout, “Sayonara!”

Robinson has always been interested in education—he scored a 1320 on the SAT, after all—so he decided to invest in a school that would serve low-income students on the East Side. There was only one problem: The Robinsons couldn’t find one that suited their needs. “We weren’t trying to reinvent the wheel,” he said. “If we had found a place that was doing something fantastic, we probably would have joined them. But we didn’t find anything that sparked our interest.” Enter the Carver Community Cultural Center. On Hackberry Street just north of Commerce, where the Carver is located, the roof of the Alamodome looms above the trees. “Going to work every day I saw how poorly developed the area was, and it’s just across the highway from the River Walk,” he said. “We wanted to have an economic impact on that side of town, and obviously we wanted to impact those kids. Everybody knows about the Carver and its history. It just seemed to be a natural fit to say, ‘Let’s build a school there.'”

The Carver has served as a meeting place for the black community in San Antonio for more than half a century. It may have begun as a product of segregation—on the north side of the complex an inscription reads “Colored Branch of the San Antonio Library and Auditorium”—but it developed into an artistic hotbed, boasting stars over the years such as Ella Fitzgerald and Paul Robeson. Now the Carver continues to offer everything from first-rate performances by Wynton Marsalis and the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra to classes on ceramics.

The academy plans to take full advantage of those offerings. In addition, it will also teach family values and a rigorous academic curriculum, with a focus on math, phonics, science, and foreign language. Obviously, though, the Carver Academy has a lot left to do. When all of the classrooms are completed, the school will enroll 290 students (currently the student body is 60 percent black, 30 percent Hispanic, and 10 percent Anglo), and the student-to-teacher ratio will be capped at fifteen to one. The price tag per student is $8,000 a year, but about 95 percent are on scholarship. That means Robinson will devote much of his time to fundraising. By early November the academy had raised $4.9 million, putting it well below the $12.4 million required to finish construction. Robinson also hopes to raise $10 million for scholarships and a $35 million endowment. He had a reason, though, for opening part of the school before he had reached the academy’s financial goals. “I’m not very good at knocking on people’s doors and asking for money,” he said. “That’s why we did this in an unorthodox manner. It’s one thing to have a bunch of brochures, but that doesn’t capture people’s imagination as much as being able to walk into the school and see kids who are so excited to be here.”

Perhaps the most interesting wrinkle in the opening of the school came this summer, when, for the first time in his career, Robinson wondered if he would even remain in San Antonio. Though the Spurs finished the regular season last year with the league’s best record, 58-24, they were trounced by the Los Angeles Lakers in the conference finals. Robinson had a slow year, however. Except for the 1996-1997 season, when he played only six games because of injuries, he played the fewest minutes per game in his career and ended up with his lowest totals per game in scoring and rebounding.

That sluggishness carried over into the off-season. Robinson needed to sign a new contract, but the process dragged on. After strained negotiations, he eventually agreed to a two-year deal worth $20 million, but he questioned whether the team even wanted him back. When I asked him if he would have retired or tried to sign with another team, he paused. “That’s a good question,” he said. “I really don’t know. I want to be where God wants me to be. If that means play, play. If it means not to play, then that’s fine.” He insisted, though, that his commitment to the Carver never wavered. “I still would have given my heart to this project. This career is temporary. There is life after basketball, whether I raise my kids and love my wife or take them to go teach or preach somewhere. Whatever I do is going to be exciting to me. There may not be 25,000 people cheering, but the students are pretty great. This is just as fulfilling.”