People in love do crazy things. That was certainly the case when Rhonda Tavey went on the lam across Texas last summer with five children aged eight and under, all of whom technically belonged to a 24-year-old black Katrina evacuee named Erica Alphonse. Rhonda, who is white, was 44, a single mother driving a Chrysler minivan with her 18-year-old daughter, Lauren, riding shotgun. “Mom,” Lauren begged as they ping-ponged from north Houston to Las Colinas to Port Aransas, “you have to tell me what’s going on!” But Rhonda wouldn’t. A stocky woman with melancholy eyes and not a shred of vanity, she was a churchgoing Lutheran and a kids’ volleyball coach, someone with an unchallenged reputation for being an “angel” with “a heart of gold.” Yet here she was, in August 2008, charged with kidnapping, the target of a statewide Amber Alert.

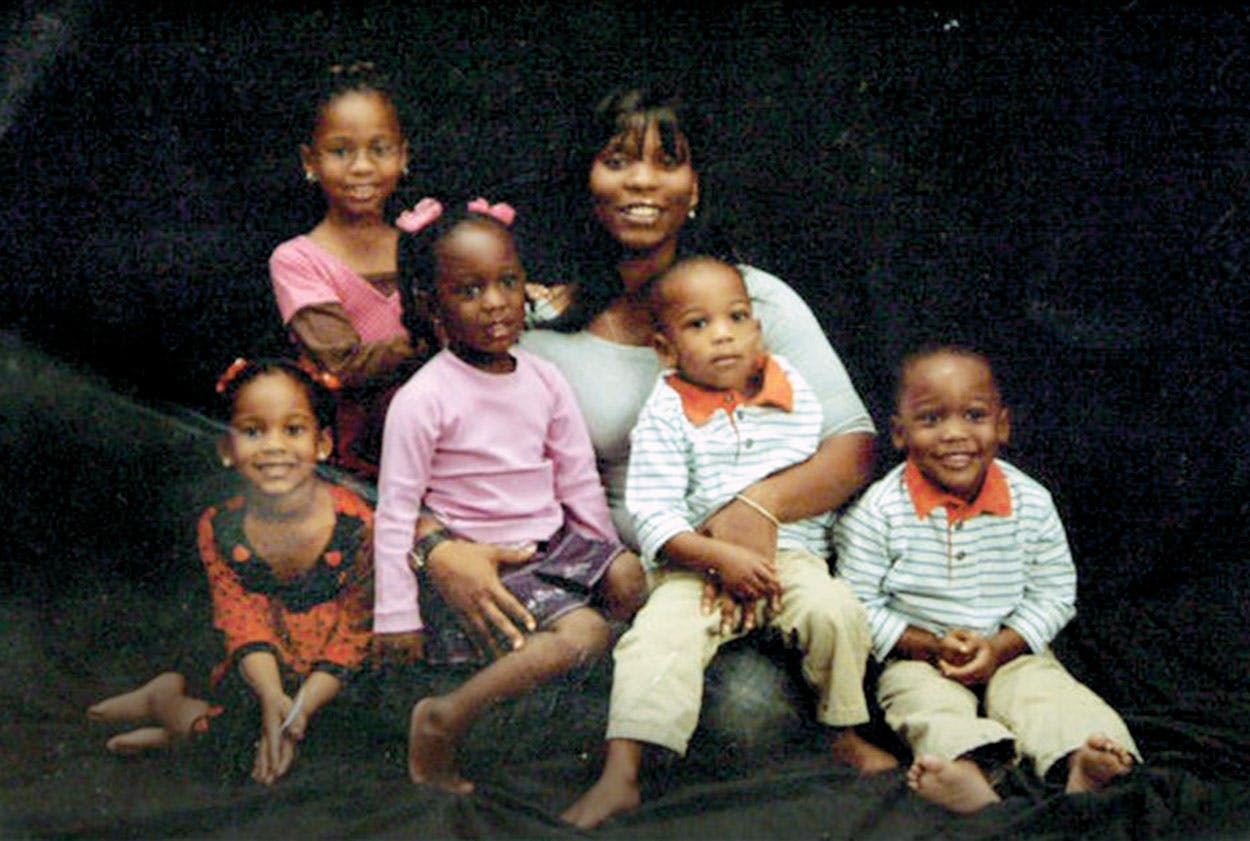

The children—three girls and two boys—sat in the backseat. The girls chattered while watching DVD players on their laps. Their braids were fastened with brightly colored balls that matched their clothes and bobbed when they talked. These were strikingly beautiful children, with burnished skin in shades from café au lait to mahogany, beckoning smiles, dancing eyes, and a knowingness that sometimes caused Rhonda to stop and stare. “My Katrina kids,” she’d proclaim proudly to gawking strangers.

“When are we going to get where we’re going?” eight-year-old Rod’Keesa demanded. She’d been five when she began living with Rhonda; she was then a tiny, spindly child who knew how to make breakfast for her little sisters and change her brothers’ diapers but didn’t know her letters. “I need to go to the bathroom,” Alaysa, who was six, called out. Seeing her happily cuddle the baby doll she’d gotten for her birthday, it was hard to recall how shy she’d been when she had first met Rhonda. “When are we going to eat again?” asked Yasmine, or Ya-Ya, who was four and had turned to a coloring book. “I want to stop at McDonald’s.” The twin boys, Erin and Eric, were asleep, safely strapped in their car seats. Like Yasmine, the boys had spent more of their short lives with Rhonda than with the woman who had given them birth. Unhurried, unworried, the children sang along every time Ra-Ra—that’s what they called Rhonda—stopped the car, took out a map, and began their new song: “Eeeny, meeny, miney, moe, tell me where you want to go!”

Sometimes Rhonda’s cell phone rang, and she would have to pull over and trot a few steps away from the car to answer, or she would step out of a hotel room to take a call when they’d stopped for the night. Naturally, she didn’t want to upset the kids. Sometimes the caller was a relative or a friend begging her to turn herself in; sometimes the call was from the Harris County constable’s office or the district attorney’s office, whose representatives suggested, in firmer tones, that she do the same thing. Instead, Rhonda kept going. She was, she explained, afraid for the safety of her kids. She wouldn’t give them back to Erica, not with what she knew.

Back in Houston, Erica Alphonse was in a panic. It was surreal, she told herself, a bad TV show. Until just a few days ago, Rhonda Tavey had been her friend—the mother she’d never had, she had told the Dallas Morning News in 2006—and now the relatives who had warned Erica that Rhonda had been getting too close to her children looked to be right. Erica was alone in Houston, with no man, a few impatient relatives, and just a handful of friends. She wept on the phone when she called family back in New Orleans. Rhonda was telling everyone who would listen—falsely, Erica insisted—that Erica was a drug user, that she had pulled a knife on Rhonda, that she just wanted her kids because without them she couldn’t get food stamps. Erica hadn’t asked for any of this—the helicopters hovering over her aunt’s apartment, the reporters camped outside, the calls from the police and the district attorney.

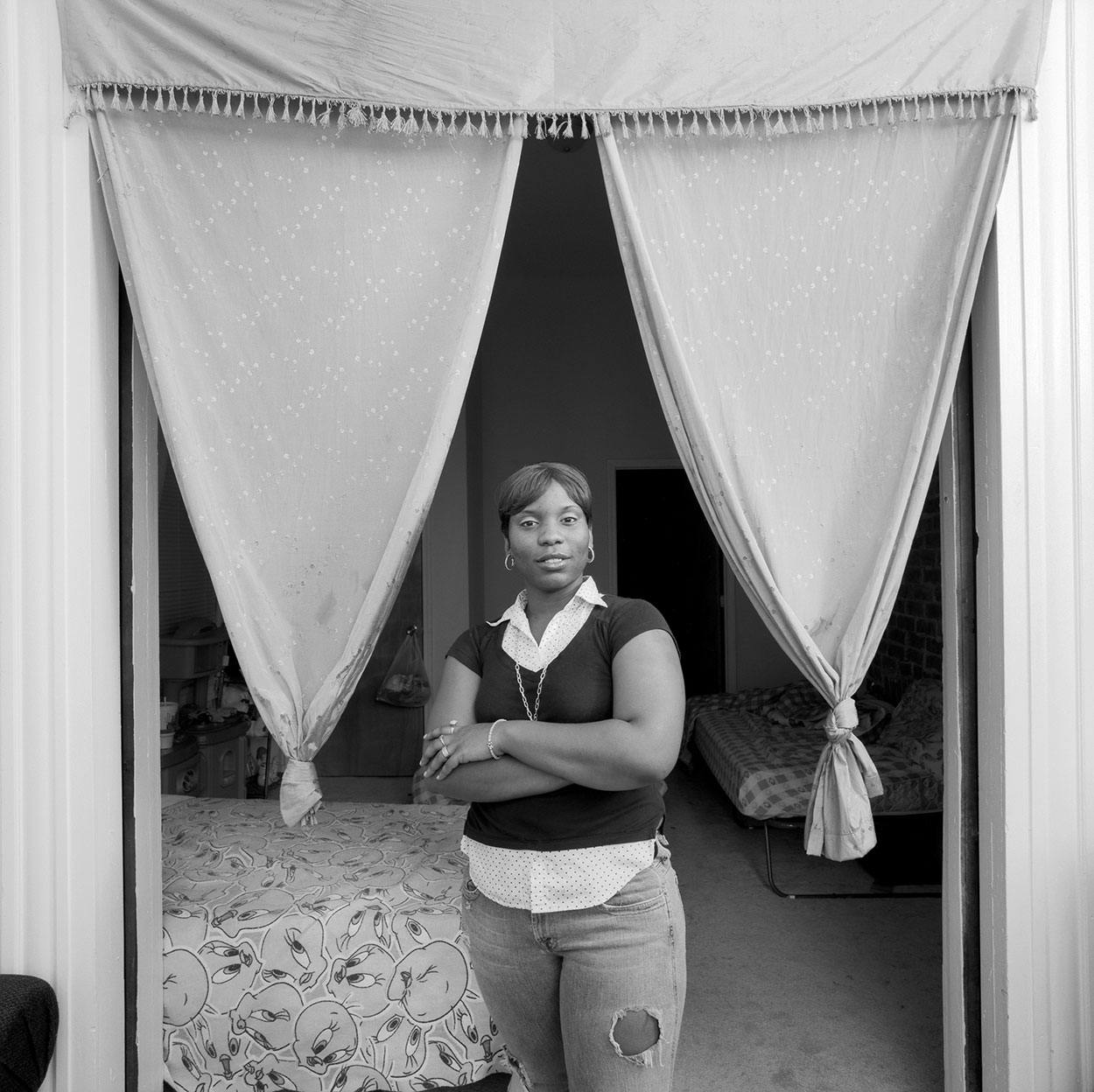

She was a pretty young woman, soft and round, with a broad smile that was so bright it could nearly erase the hopelessness of a past that included a chaotic childhood, the murder of the father of her first baby, an education that ended in the ninth grade, and five kids to look after. Erin and Eric had been just two weeks old when Katrina hit; when the levees broke, Erica brought them to safety strapped into a car seat she carried over her head through chin-deep water. She evacuated to Houston with her children and wound up at Reliant Center, where she met Rhonda, who took her in and for three years cared for the kids while Erica tried to rebuild a life for her family in New Orleans. Erica had considered Rhonda her angel of mercy.

Now a Houston police officer was giving her attitude. Erica explained that Rhonda had thrown her out of the house when Erica had made it clear that she was leaving with her kids. Rhonda had told her she would deliver the children to her later that day, but she’d never come back. Erica hadn’t wanted to call the police; she didn’t want any trouble, she just wanted her kids. It took three phone calls before the cops showed. “I can’t do anything about this,” the officer told her initially. “You left your kids with the woman.” It wasn’t until Erica described Rhonda that she got some action. “Oh,” the policewoman said. “She’s a white lady?”

“My kids are all I have,” Erica told the police, reporters, and wide-eyed neighbors, but she wasn’t sure anyone believed her. She couldn’t stop thinking about that woman named Andrea Yates who had drowned her kids in a bathtub. Erica realized, too late, that the person she had trusted with her childen was someone she didn’t know at all.

During the nearly four weeks that Rhonda spent on the run, and in the months following her arrest on five counts of kidnapping, the story became a national cause célèbre. Rhonda appeared on Good Morning America to defend herself, and the case provided the basis for the Question of the Day one morning on the Rush Limbaugh Show. In Houston, where resettlement of more than 150,000 New Orleans evacuees had become a topic of tremendous ambivalence, the story received almost 24/7 media coverage. Quanell X, the local Nation of Islam spokesperson, made a predictable TV appearance in Erica’s defense, while one of Rhonda’s loyal neighbors printed T-shirts with a photo of the children and the caption “Support Rhonda because . . . Their future is worth it.” Someone else created a “Rhonda Tavey Is Innocent” page on Facebook, which soon had 237 members.

Ultimately, their struggle came down to one crucial question: What makes a mother?

The passionate response could be seen as a bookend to the mania that had beset Houston in the immediate aftermath of Katrina. Anyone there at the time remembers the semi-hysterical beneficence that gripped the place, the feeling that every single Houstonian could and should do something to help the storm victims, many of whom arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs. This was the kind of challenge that spoke to the best of Houston; the private sector happily joined city and county officials to make up for a federal government that was, at best, incompetent. In many cases, Houstonians did more than donate food and money and volunteer at the Astrodome and Reliant Center: They took people into their homes.

Suddenly, in an unplanned and so far unacknowledged social experiment, white zillionaires were sitting down to dinner in their River Oaks mansions with poor, storm-shocked black families from New Orleans. Suburban teenagers learned for the first time what it meant to have nothing; children from the Ninth Ward saw possibilities they had never dreamed of. A whole season of HBO’s Curb Your Enthusiasm poked fun at the incongruity of the situation, but for a number of Houstonians, the experience of welcoming evacuees into their homes was transforming. Everything simmering on the back burners of American life came abruptly to a boil: racial inequality, economic disparities, the meaning of family—in short, everything that really mattered. “It was so beautiful,” one Houston woman who hosted a family of five told me, “but so tragic.”

The story of Rhonda Tavey and Erica Alphonse spoke to that experience and more. Theirs became a modern-day Solomon story, with each side fighting to possess five innocent children. That both women loved the youngsters was indisputable. Rhonda made tremendous sacrifices to provide for them, and they thrived in her care. But it was Erica’s blood that ran in their veins. Ultimately, their struggle came down to one crucial question: What makes a mother?

I met Erica for the first time while she was in hiding in southwest Houston with her kids, avoiding being served papers for a child custody suit that Rhonda’s attorneys had filed just after Rhonda was arrested. Erica was anxious to get back to New Orleans. She had a job there, and it was time for the kids to start school, but she was stuck in Houston pending the results of a Child Protective Services investigation instigated by Rhonda’s accusations. Rhonda had alleged that Erica and her partner, David Alfred, were unfit caregivers, citing incidents of drug use and physical abuse of the children, which Erica flatly denied. (“It’s all a smoke screen in defense of the kidnapping charges,” her attorney, Shelley B. Ross III, told me.)

We talked in a relative’s apartment, where the blinds were drawn and the faint smell of cigarette smoke lingered. A giant couch faced a droning big-screen TV, and the walls were covered with pictures of family. The children fluttered from the television to their mother, who sat at the kitchen table looking like an Egyptian queen. They took turns combing her weave, petting her, caressing her, and nuzzling her, in part to make sure, it seemed, that she was still there. They were dressed immaculately, in matching outfits, and they were polite and inquisitive. When they tired of Erica’s hair, they combed mine.

Even on that day, I noticed that Erica’s favorite word was “free,” as in “I love to be free” and “I wanted my children to be free.” When she used the word, her natural wariness dissolved into delight, and she seemed to lose herself in a fantasy. In fact, Erica’s is a history that Charles Dickens might reject as unworkable. It is full of common violence, complicated family relations, and good fortune that vanishes as swiftly as it appears. She was born and raised on the West Bank of New Orleans, in a down-on-its-heels neighborhood called Marrero. Her father drifted into her life only rarely—“He knew I was his child, but he wasn’t sure,” she told me with typical vagueness—and her mother saw enough hard times that several of her nine children had to be parceled out to various friends and relatives; before then, it had been up to Erica to tend to the younger kids. “My mother wasn’t the best mother,” she told me drily. When the family was split up, Erica was “adopted” by a grandmotherly figure who had been her mother’s childhood caretaker. For a short time, there was hope: Erica stayed in school, ran track, and became a cheerleader and a youth usher at church. She dreamed of one day being a doctor or an ambulance driver, and she hoped she’d have kids who would go to college.

Then, when Erica was about twelve, she got involved with a young man named Dwayne Glover who had just been released from a juvenile correction facility. “My son had emotional problems,” Dwayne’s mother, Cynthia Glover, told me. Cynthia, a handsome, supremely confident woman, was just one in a series of surrogate mothers to Erica. “Erica looked then just like she looks now,” Cynthia said, but she remembers noticing that the girl hanging around her teenage son acted more like a child than the sixteen-year-old she claimed to be. She loved to play dress-up with Cynthia’s makeup and heels. Eventually, Erica turned up pregnant, and in 1997, after the baby, also named Dwayne, was born, his father was shot and killed. “After my boy died, Erica left his son with me. If she took him away, she knew it would kill me,” Cynthia said.

Meanwhile, the woman who had taken Erica in grew sick with cancer, and when she died, Erica had to leave the house. “I was on my own at fourteen,” she said. “I wanted to go to school, but my grandma had died.” By then, she had had two more children, Rod’Keesa and Alaysa, by two different men and was raising a younger brother and sister. She would also help support another brother when he got out of jail.

The next few years passed in a haze of child care and low-paying jobs at hotels and fast-food restaurants. Then, in 2002, Erica met a man named David Alfred—known as Skip—and fell in love. She was eighteen, and Skip was nearly ten years older, with piercing dark eyes and a pencil mustache that made a tiny half moon over his lips. At well over six feet, he towered above Erica. Skip had already served prison time, a fact that did not set him apart from many of the men Erica encountered in New Orleans. She loved his wildness, and soon she gave birth to her fourth child, Yasmine. Things were tough, but she managed to keep everyone together until she got pregnant again, at which point she was diagnosed with high blood pressure and put on bed rest. A relative stepped in to take care of the children while Erica was in the hospital, but the arrangement ended when, after an argument with Erica, the woman called her to say that she could find her kids and her furniture out on the street. By the time Skip got there, all of Erica’s belongings had been stolen. “Two thousand five,” Erica said dully, “was not a good year.”

Life was about to get much worse. Erica was just two weeks out of the hospital with newborn twins and living with Cynthia in her small frame house in Algiers when, in late August, Katrina made landfall. The mandatory evacuation ordered by Mayor Ray Nagin meant nothing to them, because they had no car. Skip was in jail then, as was Cynthia’s husband. As the wind picked up, the women listened to the sound of neighbors boarding up windows or packing to leave. Erica tried to locate her brothers and sisters, but they were already scattered. Eventually she and Cynthia moved with the children to Cynthia’s mother’s apartment, in the notorious Calliope housing project, to wait out the storm. When the water continued to rise, sweeping down the street like an angry river, Erica and Cynthia knew they had to leave or they and the children would drown.

They set out on foot: Cynthia kept an eye on Dwayne while the girls hung on to Erica, floating atop the water in a tiny human chain. Carrying the twins in a car seat over her head, the water lapping at her chin, Erica was sure they were going to die. Instead, they reached a highway overpass near the Superdome; Erica wouldn’t go in because by then she had heard stories of rapes and killings. It was pitch-dark, and there was no food and only a little water. All night and all day, Erica listened to the sound of gunfire and the moans of the people around her. Someone pushed an old man down an adjacent flight of stairs when he wouldn’t stop crying that they were all going to die. His body lay there, unattended, unclaimed, for the three nights they stayed on the bridge. “There were so many people dying and crying,” Erica said.

Eventually, the small group trudged across the Mississippi River bridge back to Algiers, but Cynthia’s house had lost its roof and was nearly ruined. “It was like somebody put New Orleans in a bag and shook it,” she said. They cleaned themselves up, packed what food was left, and, after spending several more days by the side of a highway, crammed into a bus whose destination was unknown. “I made sure my whole family was on the bus,” Erica said. They arrived in Houston, at the Astrodome. By then Erica hadn’t eaten in five days. The family moved from the dome to Reliant Center and eventually befriended a Red Cross volunteer—a nice lady—who seemed particularly interested in helping them. Her name was Rhonda Tavey.

This brings back way too many spooky memories,” Rhonda told me, as we picked our way early last fall through a nearly empty apartment complex on Houston’s FM 1960. Rhonda was giving me a tour of the places Erica and the family had lived. Out on bond for the kidnapping charges and awaiting trial, she wore an ankle bracelet along with her T-shirt and jeans. Rhonda had no idea where the children she had devoted herself to for three years were. She was putting on a good front, but it was killing her.

As usual, she wore no makeup. This stroll down memory lane was sad for her, and it slowed her gait, which was normally bustling and purposeful. Where Erica is free-spirited, Rhonda is grounded. She has been known to stare down neighborhood bullies and is so handy with power tools that she has made many of the improvements in her modest north Houston home herself. As we walked around the complex, where the remaining tenants seemed sinister at best, she was unafraid, faltering only when we reached the steps of the second-floor apartment that Erica had lived in until she’d left for New Orleans, in 2006. Rhonda climbed the stair and, once at the front door, tried the knob. Finding it unlocked, she stepped inside.

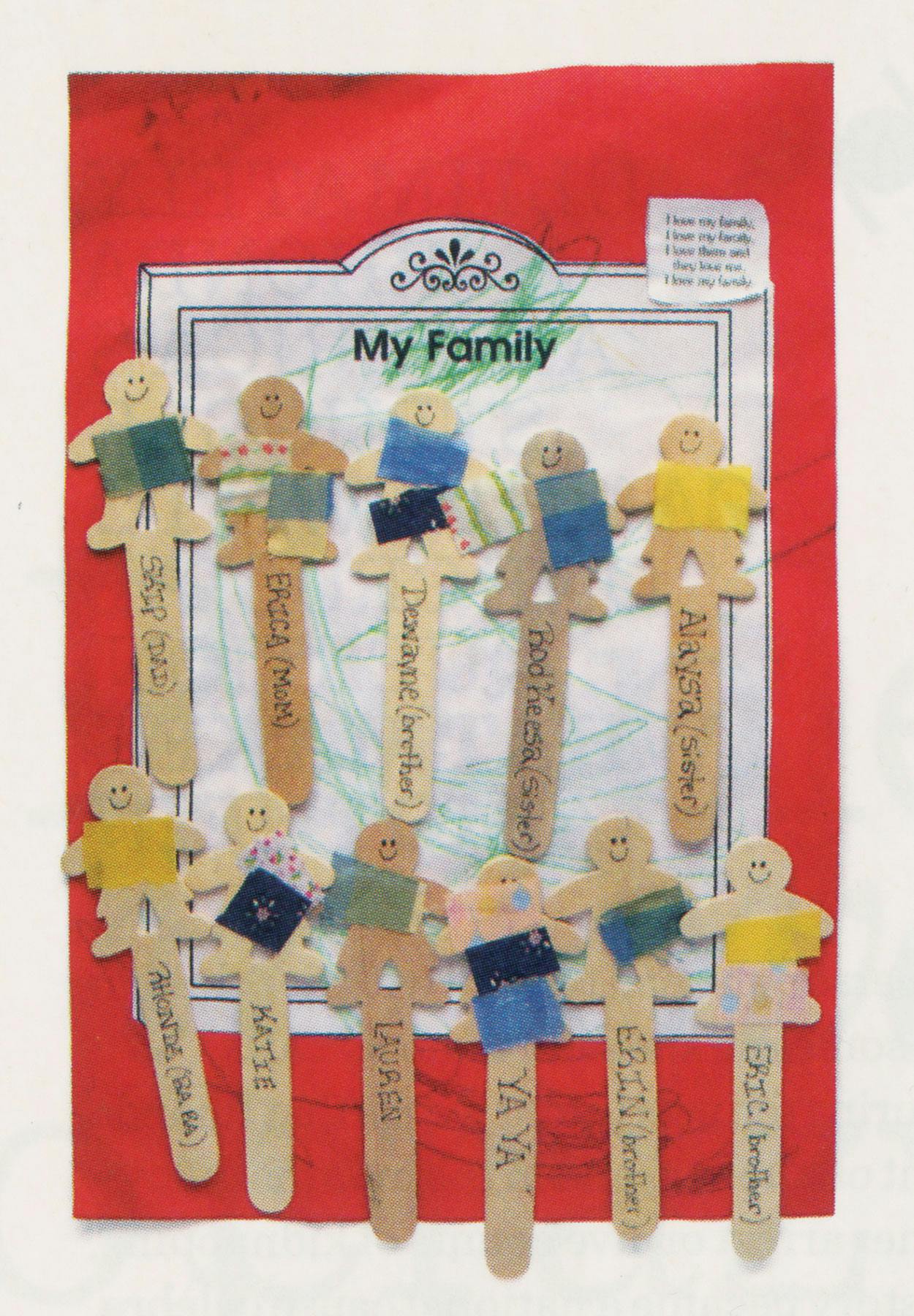

The place was a mess. At one time the apartment had probably been nice—there was a polished stone fireplace in the living room—but now it was filthy, with insulation falling from a hole in the ceiling. Rhonda showed me where Erica had nailed photos of the kids on the wall; then she disappeared into a back bedroom. “Look!” she said, showing me a pink-and-white switch plate decorated with a picture of Strawberry Shortcake. “I gave this to them!” Rhonda began rummaging through the rest of the apartment and came out of the kitchen triumphant. “This was Yasmine’s,” she told me. It was a popsicle-stick collage titled “My family,” with each stick depicting Skip, Erica, Dwayne, Rod’Keesa, Alaysa, Erin, and Eric—along with Ra-Ra, Lauren, and Rhonda’s older daughter, Katie. “I’m keeping this,” Rhonda told me, brightening. “I get little signs like that all the time.”

Rhonda’s life had never been as hard as Erica’s, but it certainly wasn’t easy. Her parents divorced when she was young, and she was raised by her mother with the support of her maternal grandparents. She had been a comely teenager, like her daughters are now, lithe as a dancer and with bright blue eyes, but she was too shy to date and preferred to spend her time playing sports or babysitting. Eventually her mother’s boyfriend fixed her up with a man who had a good job with a jewelry store chain, and after they married, Rhonda made herself into the perfect company wife, dressing up and giving parties. But according to her mother, she never seemed happy until her girls, Katie and Lauren, were born. Several years later, when Katie was hospitalized with a life-threatening illness, Rhonda’s husband left one day and simply disappeared from his family’s life. He and Rhonda divorced in 1999, and soon she had to file for bankruptcy.

Though she tried starting various businesses—she makes trophies to earn a modest living—Rhonda really excelled at one thing: taking care of children. Her own daughters were exemplary students who eventually won full scholarships to college. Whenever friends of the girls’ found themselves in trouble, they knew they would be welcome at Rhonda’s, sometimes for years. Everyone in the neighborhood understood that if they needed help, Rhonda Tavey was there—she was selfless, in the best and worst sense of the word, someone who lost herself in the care of others.

A few days after Katrina hit New Orleans, Rhonda had an appointment in the Houston Medical Center; her doctors told her she would need extensive tests to rule out a recurrence of a rare form of breast cancer that had required surgery earlier in the year. On that day Rhonda was flat broke, with no health insurance. Weeping as she drove away from the appointment, she spied the buses around the Astrodome, and, as she later told me and many others, “God took hold of my steering wheel and turned it around.” She parked the car, strode into the sea of desperate humanity, signed up to volunteer with the Red Cross, and went to work. The next day she came back with her girls. Lauren, helping with the children, met the Alphonse family. “We just kept going back to them,” Lauren told me.

Within a few months, Rhonda had assumed a role familiar to many Houstonians who took in evacuees: She became chauffeur, nurse, accountant, cook, teacher, and therapist. She helped Erica and Cynthia fill out FEMA forms and get their food stamps transferred to Houston. She took them to Gallery Furniture for the free or discounted home furnishings provided to Katrina victims and helped them find apartments that had also been discounted. She drove them to job interviews and, when they were hired—Erica worked for a time at Wal-Mart, as a cashier, and at Bush Intercontinental Airport, driving the train between terminals—drove them to work in the morning and home at night. She found a school for Dwayne, who was then eight, and a kindergarten for Rod’Keesa; the girls went to preschool for free at her church while she cared for the infant twins. According to Rhonda and her family and friends, Erin and Eric lived with her full-time while Erica stayed at her own apartment. It was Rhonda who got up in the middle of the night to feed them; that way, Erica could be fresh to work the next day. Soon all the children except Dwayne were living at Rhonda’s most of the time.

Rhonda’s house on Brooklawn filled up with toys, courtesy of various charities, and Erica, for the first time in her life, had some freedom. She pitched in with expenses by contributing her food stamps, and as she and Rhonda got to know each other, their relationship took on familiar mother-daughter contours, each woman sharing histories and heartbreaks. Rhonda encouraged Erica to stop swatting at the kids and to switch off The Jerry Springer Show when they visited the apartment. Though Katie was away at college, Lauren gladly served as a role model and back-up babysitter, correcting the children’s table manners and handling their tantrums. The kids were so unaccustomed to the bounty at Rhonda’s that at first they stole food and hid it under their beds; Rod’Keesa ate so fast that Rhonda had to put a timer on the dinner table to teach her to slow down. At night the children clambered onto the couch with her, fighting for her lap while she read them a story. “Everyone would always tell us, ‘I hope their family is thankful for all you’re doing,’” Rhonda told me. “But I was chosen by God to do this. They gave back to us more than anything. On a daily basis they gave to us.” At night, the twins fell asleep holding on to Lauren’s ponytail.

The situation seemed to be working well for everyone. In November 2006 Rhonda and her daughters spent Thanksgiving in New Orleans with Skip’s extensive family. His mother, Lillian Melson, cooed over the twins, whom she had never seen, and served Rhonda and her girls heaping helpings of gumbo, turkey, and ham. The Dallas Morning News profiled Rhonda and Erica in a heartwarming holiday story titled “A Bounty of Blessings,” in which Rhonda said, “I couldn’t love these kids more if they were my own.” Erica agreed. “I could count on one hand the number of people who loved me when I was small,” she told the paper, but now her children had “more love than I ever had.” She talked about getting her GED and maybe going to trade school, about finding a better job so that she could begin to save for her kids’ college education. Rhonda, she said, would always be involved.

“I told her, ‘You’ll always be in my life. If I decide to come back to New Orleans, my children will come back to see you every summer, every holiday.’ I haven’t seen my children that happy with anybody, period. They’re not used to doing all the stuff they’re doing with Rhonda,” Erica said. “I can’t take that from them.”

It’s hard to tell when, exactly, the problems started, but to some extent—and not surprisingly—they had to do with a man. Skip, in jail when Katrina hit, was by that time well on his way to becoming a career criminal. Though he came from a respectable, hardworking family, the lack of jobs and the lure of the streets had made for an unfortunate combination. His record started in 1995 with a plea of guilty to a second-degree battery charge, for which he received three years’ probation; in 1999 he pleaded guilty to manslaughter and was sentenced to five years in prison. Skip’s family claims that he didn’t commit every crime he was arrested for, an assertion that has some validity in a city that can hold suspects for up to sixty days without being charged.

The fact that he was still incarcerated while Erica was in Houston weighed on her, and depression would set in, sometimes so badly that Rhonda would have to pull her out of bed. When Skip was released from jail several months after the storm, he came to Houston to see Erica and a woman who may or may not have been his wife (Erica told Rhonda she was). In 2006 the Houston police charged him with assault on a family member. This may have been why he began urging Erica to return with him to New Orleans; another possible motivation was Rhonda’s presence. She recalls that whenever she visited Erica’s apartment, Skip never seemed to be doing much but playing video games or watching TV. When she found bruises on Erica during one of her visits, she followed him outside when he was taking out the trash and told him to never touch Erica again. “I wasn’t afraid of him,” Rhonda told me.

Still, Skip prevailed. Erica knew how sad her kids would be if she left—they’d cried when she had taken short trips back to New Orleans—but maybe now there was a real chance to make a life as a family. The storm had temporarily destroyed the wide net of friends and relatives who helped with the kids and shared what they had, but people were going home. For Erica, like many evacuees, the longing for New Orleans ran deep: the food, the music, the aromas, the ways of being that never seemed to change. There was work to be had rebuilding the city, Skip told her; he was already making a living repairing roofs. They could be together with the kids. And Erica was lonely with nothing but work to occupy her time. “I got tired of being in Houston by myself,” she told me.

Rhonda, however, was dubious. “You don’t need to go back,” she told Erica. After all, the children were doing well in Houston. Initially, Rod’Keesa had been nearly impossible to control at school; one teacher told Rhonda that the girl’s behavior had made her fear for her safety and that of her students. But thanks to Rhonda’s guidance—good school reports earned a weekly shopping spree at a dollar store—and the inspiration to get her involved in track, where Rod’Keesa immediately excelled, most of the problems vanished. She had some learning disabilities, but she wore glasses now to help with vision problems, as did Alaysa, who had complained of not being able to see the blackboard. Lauren had found a black church near their home and started taking the children every Sunday. Life in the sections of New Orleans hardest hit by Katrina, meanwhile, was still disastrous. There were no traffic lights, no stop signs; the debris and mud from a year ago covered the streets. Many of the schools weren’t yet open.

Nonetheless, by early spring 2006, Erica had resolved to return home. She planned to stay at her sister’s house, along with her brother, his wife, and their children. When Rhonda suggested that Erica leave the kids with her in Houston, Erica thought it over and finally agreed. “She’d been with us that long, and we knew her pretty well,” Erica told me, adding, “We thought we knew her well.” Rhonda drew up a short contract dated March 2006 and had Erica and Skip sign it. The notarized document gave Rhonda temporary guardianship over the children while Erica looked for a job and a permanent place to live. In turn, Erica and Skip agreed to reimburse Rhonda for out-of-pocket expenses.

Erica studied the woman who had been her friend and confidant. “My children aren’t for sale,” she told her.

It is here that the women’s stories begin to diverge. Erica says she called frequently when she was gone; Rhonda says not so much. Rhonda says Erica sent “not a penny” of support; Erica says she did. Erica remembers her children being tearful at every parting; Rhonda does not. The frequency of Erica’s visits to Houston is, in fact, a major subject of debate: Though Erica says she returned every few months, even friends and relatives in New Orleans warned her that that wasn’t enough and that Rhonda was trying to take her children. Rhonda says she had to beg Erica to come for Halloween (Rhonda made costumes with a Wizard of Oz theme) and Christmas (when she found charities, friends, and relatives to donate mountains of toys) and that often when Erica came, she was sullen and remote. At least once this had to do with the fact that Skip was in jail again, this time on a charge of aggravated rape and kidnapping. Other times, Rhonda says, Erica was disruptive, as when she telephoned on Rod’Keesa’s birthday and told her daughter, right before the party started, that one of Rod’Keesa’s friends had been killed by a stray bullet.

Rhonda said nothing, even though she too was getting pressure from friends and family, who told her that Erica was taking advantage. “She just never had anyone care about her,” Rhonda said. Her mother could not see how Rhonda could attend to her own health, her daughters, and Erica’s children. “You can be a mother to those kids, but that doesn’t mean you are their mother,” she cautioned.

Rhonda ignored her. She trusted Erica so completely that when Erica decided to take the kids to New Orleans for the summer of 2007 and Lauren begged to go along, she agreed. Erica was then working at a Papa John’s and as a cashier at a restaurant at the city’s aquarium. Skip had a job on the wharf. Looking back, Erica recalls her children’s visit as a happy one. “They could be free,” she told me. “Just be themselves.”

There were problems, though. After a few days, Lauren called to say there was no food in the house. Rhonda overnighted cash and then sent a big package of canned food. Several days later, Rhonda got phone calls from both Skip’s mother and one of Erica’s relatives. Did she know what kind of neighborhood Lauren and the kids were staying in? There were drugs and guns; it was one of the worst in New Orleans. They told Rhonda to get the children back to Houston and fast, before someone got hurt. They could return when Erica found a better house in a better neighborhood. Rhonda couldn’t rescue the children because her van was too run-down for the drive. “I said, ‘Screw it,’” she told me. “I used the mortgage money to buy airline tickets.” The summer stay had lasted a little less than two weeks. Erica did not protest. “The neighborhood wasn’t like I thought it would be,” she told me.

That Christmas, Erica found herself back in Houston. “It was sad,” she said. “Skip got incarcerated, and I was all by myself.” Rhonda and Lauren had pooled their money to make sure the kids had a big Christmas, but Erica couldn’t marshal much enthusiasm for the giant toy cars her kids raced up and down the driveway. Riding on the train back to New Orleans after the holidays, she told herself that Skip had been wrongly accused of the rape and vowed to help with his case. She also reached another decision. When she arrived home, she found a duplex in an old house in Mid-City, a working-class area of New Orleans. It had four rooms, along with the kitchen and the bathroom, and the school bus stop was just a few blocks away. Granted, it wasn’t the best neighborhood in town, but it was far from the worst. It was a good place for the kids. The time had come for them to live together as a family again.

Erica, Cynthia, and Skip’s mother, Lillian Melson, all say that it was made very clear to Rhonda that Erica would be coming to Houston in June 2008 to retrieve her children for good. Rhonda has no such memory. “That might have been in her mind, but I didn’t know anything about it,” she told me. But by that time, the relationship between the two women was fraying. In Rhonda’s opinion, Erica’s visits and phone calls to Houston had become even less frequent, and when she did come, she complained about Rhonda’s parenting style. “You’re spoiling my kids,” she told her. Maybe she felt she couldn’t replicate the life Rhonda had made for them; maybe she felt she and her children were growing apart. At track practice, when Rhonda thought Rod’Keesa deserved praise and encouragement, Erica carped about her performance, even when she did well. When Erica arrived in Houston in June, she seemed particularly tense. “She had a chip on her shoulder,” Rhonda said. “We felt like we were walking on eggshells.” Rhonda attributed this behavior to the news that two New Orleans friends had been murdered in a drug deal—which she says rattled Erica and caused her to want to move to Houston for good—rather than the fact that Erica might have been anxious about final goodbyes.

After two weeks together, on July 11, things came to a head. According to Erica, Rhonda woke her at six-thirty in the morning with an idea. She told Erica she had stayed up all night cleaning and thinking things over. “Hear me out,” she said. Then Rhonda offered her a $99 cell phone, a bus ticket, and a food stamp card to go back to New Orleans without her children.

Erica studied the woman who had been her friend and confidant. “My children aren’t for sale,” she told her. Later she explained to me: “I knew Rhonda was attached, but she wanted me to be that person who was gonna run off and leave her kids, and I wasn’t that person. My mama gave me up, and I don’t want to do that to my kids. They need to be with me. She knows all I’ve got is my children. If I wanted to give them up, I never would have had them.” (Rhonda denies that this episode ever happened.)

Later that day, the two went to Wal-Mart with the girls in tow. Erica noticed that Rhonda was stocking up the grocery cart as usual. “Why are you buying so much food when we’re leaving today?” she demanded. In Erica’s account, Rhonda refused to speak to her from then on. The two women dropped Erica’s daughters off at a friend’s house to swim. Erica got even angrier when they reached Rhonda’s home and she realized the twins had gone on a camp-out with Lauren and some family friends. “Why did you let them go away for the weekend when I’ve been telling you we were leaving?” The two women argued furiously. “You’re raising my kids to be like white children!” Erica screamed. Then, according to Erica, Rhonda left the house, she assumed to pick up the girls.

Rhonda also recalls that Erica became enraged at Wal-Mart, though she claims not to know why. Starting with their return home from the store, her story is significantly different from Erica’s. A few nights before, she had been folding laundry and spied some of her financial records for the kids stashed in Erica’s suitcase. Now, back at the house, she confronted Erica about taking them; Erica in turn accused Rhonda of withholding thousands of dollars in donations for the children. (At the time there was $6,000 in an account created for the Alphonse children by Rhonda’s church.) Rhonda says that she walked to the kitchen to calm down and that when she returned, Erica was holding out a pocket knife. In a story Erica categorically denies, she told Rhonda she would “see her grave” and that Skip would be coming to Houston to ask some questions of his own. Afraid for her life, Rhonda fled.

But she did not go to get the girls. Instead she ran to a neighbor’s house. He suggested they go to the nearby black church to speak with the pastor, Marcel Miles. A soft-spoken man with a thoughtful demeanor, he listened carefully to Rhonda’s accusations and became alarmed when she told him that Erica had a knife and that she herself owned a gun. He drove back to the house with Rhonda and tried to quiet both women in the front yard. “I just want to take my kids and go home,” Erica told Miles. “You need to give those kids back to their mother,” he told Rhonda. “That’s the right thing to do.” (Rhonda does not remember this exchange.)

Instead, Rhonda entered the house, returned with Erica’s suitcase, put it on the front step, and locked the front door. When Erica realized she couldn’t get back in, she asked Miles for a ride to a nearby convenience store, where a friend could pick her up. She called Rhonda on her cell, and Rhonda told her she was picking up the girls. Sometime later, Rhonda called Lillian, with whom she had become close, and gave her a cryptic message: The kids were safe. “Rhonda,” Lillian answered. “Don’t do the wrong thing. It will come back to haunt you.”

“But they’re my babies and I don’t want to lose them,” Rhonda told Lillian.

“You’re not their mama,” Lillian chided her.

“But I’m their white mama,” Rhonda replied. Alarmed, Lillian called her son and told him to get to Houston. Something was very wrong. In the meantime, Erica called, hysterical. “I told her, ‘Erica, you’re gonna get your children. Don’t never give up. God is good.’”

Erica tried to call Rhonda again when her ride arrived, but there was no answer. She tried a few more times before heading to a relative’s house, thinking she would give Rhonda a few hours to cool off. When she finally went back to the house with Skip later that night, it was empty, the yard free of toys. Rhonda and the children were gone.

Rhonda was about to cross a line that would have been inconceivable three years before. She stopped briefly at her mother’s house after picking up the girls, then connected with Lauren and the twins, returning from their weekend trip. Then she set out for a friend’s house in Katy. At a women’s shelter there, she told the story of Erica’s pulling a knife on her and added more elements that raised the stakes even higher: that Erica was a drug user, that Skip was violent, and that the children had been abused. According to Rhonda, the women at the shelter—who would not comment for this story—told her to stay in hiding, because unless she found a lawyer and filed for custody immediately, the children would go to Child Protective Services, who would return them to Erica. Convinced she would be found before she could decide what to do, Rhonda hit the road again.

She did, however, respond to calls from the constable’s office and the district attorney’s office and told them that the children were safe. Among law enforcement officials, there was some confusion about whether they had the legal right to file kidnapping charges; technically, Rhonda had permission to take care of the children. Assistant DA Jane Waters in particular wanted to keep the story out of the media, knowing the dispute would be much harder to resolve if news of it leaked. But Rhonda ignored all requests to turn herself in. She stuck to her story: that she had had the children since 2005 with little help, financial or emotional, from either Erica or her partner. Erica wanted them back only because her FEMA money was running out and, without the children, she couldn’t get enough food stamps to resell for cash. Furthermore, Rhonda said, Lauren had witnessed the sale of drugs while at the house in New Orleans. Rhonda did not feel safe returning to Houston or turning over the kids.

Three weeks into the standoff, Rhonda gave an interview to a Dallas TV reporter, repeating all the allegations while she cuddled the children. Waters, fed up—“Rhonda wanted to call the shots regarding her surrender,” she told me—filed kidnapping charges, and the Texas Center for the Missing issued an Amber Alert. Rhonda was on her way home to turn herself in when the FBI arrested her at her grandmother’s house in Houston on August 8. Rod’Keesa asked if they were all going to jail. “Do me a favor,” Rhonda asked an agent in an FBI jacket. “Take that jacket off so you don’t scare my kids.”

Predictably, both women became media stars and, not coincidentally, symbols of different views of motherhood. At her first televised press conference after her arrest, in the famous law offices of DeGuerin and Dickson, Rhonda presented herself as the good mother who had been driven to the brink by the neglectful, unfit Erica. While a cameraman focused on Rhonda’s ankle bracelet, she made the somber promise, “If I had it to do again, I would do it again. I would lie down and die for these kids. . . . I miss them desperately. I miss them every day. But they know God; they know how to pray.” Her attorney, Todd Ward, a young protégé of Dick DeGuerin’s, summarized Rhonda’s actions more simply: “No good deed goes unpunished.”

Erica, in turn, made a case for herself as the struggling but hardworking mother who had been betrayed by a friend who “went bananas.” In a story titled “Mom pleads for kids’ return” on a KHOU TV news broadcast, Erica appeared worried but resolute, flatly denying that she used drugs or that she wanted her kids back for nothing more than a government handout. “I work,” she pointed out, while conceding unapologetically that she relied on food stamps to feed her children. She also refused to go on the offensive: “I don’t have anything bad to say about Rhonda, because she’s been good to me,” Erica said. “Rhonda, you’ve been my family for three years. I know you grew accustomed to loving my children. I grew accustomed to loving you. I never thought you would do this to me. You said yourself you would never take my children away from me.”

To a large extent, Rhonda won the media war. When the kidnapping became the subject of Rush Limbaugh’s Question of the Day—“Who should have the kids, the caretaker or the mother?”—it was Rhonda, not surprisingly, who got the radio host’s support. In cyberspace, the story that had once served as an allegory for racial harmony quickly became a means for bloggers to vent their prejudices. Though Erica was not without her share of supporters—“Ok, what if the BLACK mother had kidnapped Tavey’s 5 WHITE kids because she ‘cared’ about them! Every government agency from the FBI to the CIA to the IRS to HPD etc. would’ve flocked to Houston,” wrote one on KHOU’s Web site—many others aired their post-Katrina resentments, unable to believe that a poor woman actually loved her kids. “This is the thanks someone gets for trying to help a Katrician,” posted another. “I hope for [Rhonda’s] sake that the children are returned to their mother in New Orleans. Even raised properly, they would only stab her in the back at the end.” Erica’s attorney, Shelley Ross, was particularly disappointed that the local churches and charities that had been so supportive in the wake of Katrina were now keeping their distance, a sure sign that Houston had wearied of its caretaker role. “People want to say without saying that Erica is a typical poverty-stricken mom,” he said. “Her values aren’t what they should be, and this justifies Rhonda’s position.”

Thanks to the law, however, Erica got her children back. Rhonda’s allegations of child abuse and family violence had all surfaced after Erica had arrived in Houston to reclaim her family, which made Rhonda suspect in Waters’s eyes. The truth of these accusations may never be known; the infamously overstressed CPS carefully investigated Erica’s life in New Orleans and gave her a drug test (she passed) but never called the six people that Rhonda said had witnessed abuse in Houston. Estella Olguin, a CPS spokesperson, noted that when the kids were reunited with their mother, they were joyful. “It wasn’t children who didn’t know her,” she said. Added Waters: “It is a question of whether Rhonda had a legal right to do what she did. She had none. Maybe Rhonda could provide a better home, but we’d have chaos if everyone took the law into their own hands this way.”

In October a Houston grand jury decided not to indict Rhonda on the kidnapping charges, due largely to a convincing packet assembled by Ward that included Skip’s criminal record and the agreement signed by Skip, Erica, and Rhonda. At the same time, Rhonda withdrew her suit for custody of the children, though she was noncommittal about future plans. She told the local news that her home was always open to Erica and her children. When Erica, who had left for New Orleans with the kids, learned of the offer, she said, “She must think I’m crazy.”

One hurricane began this story, and another ends it. I saw Rhonda for the last time after she was set free, and after Hurricane Ike had cut its murderous path through Houston. Her house had not been spared. An aluminum awning lay mangled in the backyard, and most of the roof was torn off. Another sudden storm had sent water flooding into the house through her damaged roof, and no amount of pots, pans, and towels could stop it. “FEMA said my house was livable,” she told me. Pictures of Erica’s children still filled the walls, and a small shrine with Rod’Keesa’s track medals hung near the girls’ bedroom, where many of their toys were still crammed into their bunk beds. The boy’s twin beds, in the shape of fire trucks, sat in one corner of Lauren’s room. “It’s so quiet,” Rhonda told me. Not entirely: A slim, pretty teenager—a friend of her daughters’—came by and dropped off her baby for Rhonda to care for. Rhonda cooed to the child, trying to get him to sleep while we talked.

In New Orleans, Erica’s life had almost returned to normal. I got to her house at six-thirty one October morning, having offered to help her get the kids to school. The small house was clean, and Rod’Keesa was already up and dressed when I arrived. For her lunch, Erica rolled up a half-eaten bag of chips and put it in her backpack. In Houston, Rhonda had worked hard to clear up the children’s asthma; now most of them had runny noses, maybe because of the cigarette butts filling the ashtray by Erica’s bed. Neither Rod’Keesa nor Alaysa was wearing her glasses, though Erica said she intended to get them new ones. Erin and Eric, who had been almost toilet trained by Rhonda, were back in pull-up pants. Skip was in jail again on a robbery charge; Erica had taken in one of his daughters by another woman. Despite the obvious difficulties, Erica’s children were the same charming, loving, inquisitive kids they had been in Houston. (“I want to go to your house,” Eric told me.) How much of that was Erica’s doing and how much was Rhonda’s was impossible to know. It was clear, however, how much these children loved their mother and how much she loved them. She ironed their shirts and combed their hair and found their shoes under beds, and all the while, their eyes followed her every move.

Erica seemed worn, and sometimes she batted at the children impatiently; every once in a while her voice took on a sharp edge. She was working, intermittently, as a housekeeper at Tulane University, but, she told me, “Mexicans” were now taking all the good jobs. Hopefulness was not a quality she put much stock in; nothing in her history suggested it should be. Rhonda’s betrayal, in her eyes, would become just another in a long line, another grim and preposterous tale that could be used to prove a larger point.

I offered to walk Rod’Keesa to her bus stop. The sun wasn’t up, and the streets of the Mid-City neighborhood were faintly menacing, the porches of the small frame houses still dark. A sharp, cool breeze scattered leaves and signaled the first signs of autumn. Erica, wrapped in a blanket, stood on her porch and watched us walk a few blocks to a busy intersection.

Rod’Keesa was, even at this hour, ebullient and preternaturally self-assured. No, she didn’t like school. Her teachers were mean, she chirped. The ponytail pulled high atop her head bounced in agreement when she talked. At the bus stop, cars whizzed by at high speeds, but very few people were out and about. Under the predawn sky, Rod’Keesa, despite her confidence, seemed tiny and insignificant, more alone than she knew. A middle-aged white woman, I thought, wasn’t much of a guardian angel here.

Rod’Keesa spied a friend who was waiting safely in a warm car with her mother, the windows rolled up and the doors locked. Rod’Keesa, waving, went to the window to say hello. I looked up and down the street for the bus, which was nowhere in sight. Then I looked at the woman behind the wheel. “Can you keep her?” I asked.