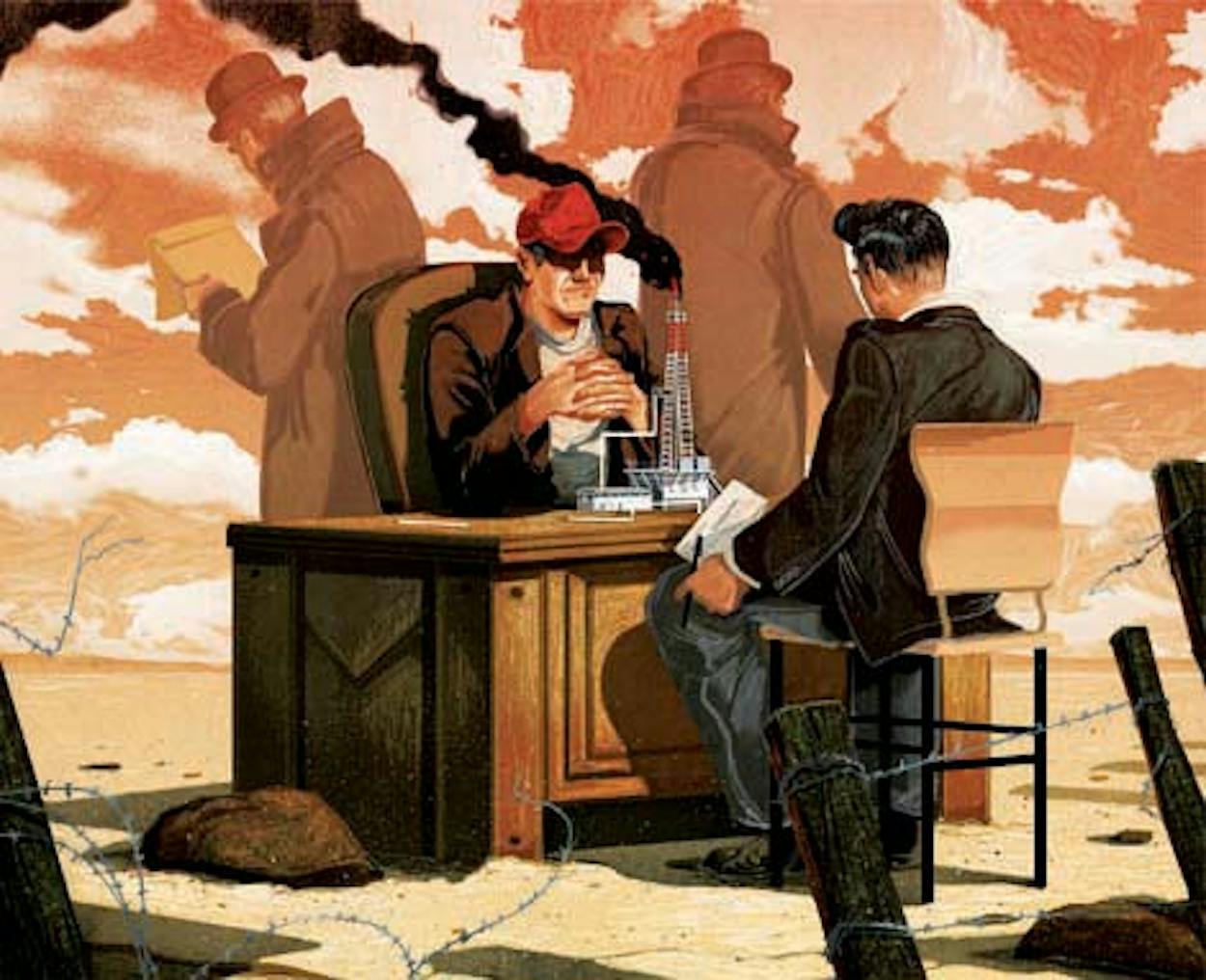

You couldn’t pick a more unexpected swindler than Joseph Blimline. Unlike the trim and dapper Allen Stanford, who was partial to bespoke suits, Blimline was heavyset and nearly always wore jeans, a T-shirt, and an orange baseball cap. But in May, about a month before Stanford’s sentencing, 37-year-old Blimline stood in a federal courtroom to accept a twenty-year sentence for running his own Ponzi schemes.

Working from nondescript buildings on the Dallas North Tollway and passing himself off as a reputable businessman, Blimline had helped bring in more than $500 million from individual investors by promising them eye-popping returns from the sizzling natural gas business in Texas and Oklahoma. Though that figure is far less than Stanford’s $7 billion swindle, what makes Blimline’s cons so audacious—and the tale such a cautionary one—was that he raised a lot of that money while in sight of regulators, including the FBI.

Much has been made about the Dodd-Frank legislation and other regulations intended to rein in Wall Street since the dark days of the 2008–2009 financial crisis. But for all the noise, Blimline’s story is a painful reminder that no one is watching out for the average investor. “You can’t be less regulated than this,” says Daniel Girard, a plaintiff’s lawyer who represented investors in a related civil case.

Originally from Pennsylvania, Blimline moved to Wichita Falls when he was in his mid-twenties with little more than a high school diploma. (His bio later claimed a degree from the “Dale Carnegie Management School,” apparently a short business seminar.) He soon became interested in buying natural gas properties, and between 1999 and 2002, he raised about $1 million, enough to give him some experience with other people’s money. In 2003 Blimline persuaded two associates from Michigan, Eric and Jay Merkle, to get in on the action. Tapping family and friends, the brothers ultimately helped bring in about $45 million by offering outrageous returns of up to 72 percent a year.

In soliciting the money, the Merkles and Blimline had taken advantage of a loophole that is the backbone of start-ups and small businesses: under the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Regulation D, businesses can sell securities without SEC review if their investors are “accredited,” or wealthy enough to take such risks. Last year, an estimated $1 trillion was raised through Reg D offerings.

Blimline eventually moved to the Dallas area, where he bought some gas properties for several companies, including one he called Jordan River Resources, but they were often marginal investments, purchased at inflated prices. As new money came in, he used some to pay early investors, but according to court documents, about $5 million went to Blimline himself, who was developing an appetite for expensive toys, buying a Chevy Corvette, a Lincoln Navigator, and a Dodge Viper.

The scheme began to fall apart after an investor who did not get his money back alerted the Michigan Office of Financial and Insurance Services, which started poking around in April 2005. In March 2006 Michigan regulators fined Blimline and the Merkles $1,000 each for sloppy paperwork, and in July of that year, they were ordered to stop selling unregistered securities in Michigan and to refund investors’ money. Not long after, a bank called the FBI after it noticed large sums of cash moving through a Merkle account. The agency began to question the brothers and their associates.

Like a good running back who patiently follows his blockers, however, Blimline managed to stay just out of reach of investigators. Unfazed by the crumbling Michigan operation or the FBI investigation, he began building a new business in Dallas, called Provident Royalties. He teamed up with another investor, Russ Melbye, and two entrepreneurs who had bought a securities firm, Henry Harrison and Brendan Coughlin, and the four began to sell unregistered preferred stock in a series of oil and gas entities, promising annual dividends of 14 to 18 percent. Though Blimline was a founder and occupied a corner office, his name was dropped from the offering documents because of his troubles in Michigan.

Provident hit a gusher. His new partners tapped into a network of brokerages, ranging from mom-and-pops to Securities America, then a unit of Ameriprise Financial. With Provident’s offer of commissions that were as high as 8 percent, plus another 1 percent “due diligence” fee, hundreds of stockbrokers were all too willing to sell Provident’s promises to their clients.

Not surprisingly, the money poured in. Between mid-2006 and early 2009, Blimline’s company tapped approximately 7,700 investors to raise more than $480 million—nearly eleven times what had been raised in Michigan. As with the earlier deals, new investor money was used to pay dividends to original investors, creating the image of a successful enterprise. For instance, one entity, Shale Royalties 5, paid more than $4.5 million in dividends in 2008, though its total revenue was just $121,136.

Blimline did invest some money in natural gas properties, but he never was good at securing clear titles. He was top-notch, however, at spending money. He acquired some seventeen ranches, nine mostly modest houses, a couple of BMWs, and a Cessna Citation jet. He also frequented high-end Dallas strip clubs, once dropping $65,000 in a single day. (Through his attorney, K. Lawson Pedigo, Blimline declined to be interviewed, but Pedigo explained that his client “had a zest for living.”)

In February 2007, as Provident was taking off, the FBI interviewed Blimline about the Michigan mess. The next month, the bulk of the Michigan entities filed for bankruptcy. Late that year, a trustee put some of the Blimline-purchased properties up for sale. There were no takers—until Blimline, in a brassy move, bid for them with Provident investors’ money, hoping that he would escape serious penalty if the Michigan investors got their money back. (An investment firm later described the properties that Provident purchased for $22 million as “goat pasture.”) Then, in early 2009, after natural gas prices plummeted, investor money dried up. Provident landed in bankruptcy in mid-2009.

All of which leads to the million-dollar question: Where were the regulators? The Texas State Securities Board never was formally involved. Alerted by irate brokerage customers, the SEC office in Salt Lake City, Utah, sued Melbye, Harrison, and Coughlin shortly after the Provident bankruptcy. But because Blimline wasn’t disclosed as a partner, regulators didn’t catch up to him until six months later.

The FBI investigation focused first on the Merkles, who were indicted in 2008, pleaded guilty to securities fraud (among other charges) in 2009, and received ten-year sentences. Finally, in mid-2010, the Department of Justice filed cases against Blimline in both Michigan and Texas. They were consolidated in Texas, and in August 2010 Blimline finally pleaded guilty as well.

The FBI declined comment, citing related cases that are pending. But in press releases announcing Blimline’s sentencing, the FBI said the case reflected “the hard work performed by agents committed to stopping this type of fraud.” John M. Bales, U.S. attorney for Texas’s Eastern District, praised how Michigan and Texas agents worked with federal and state regulators to untangle the schemes and “bring the perpetrators to justice.”

While Michigan investors have gotten about 40 percent of their money back, it’s unclear how Provident investors will fare. What is clear is that investors should expect similar schemes in the future. A provision in the new JOBS Act will allow promoters to advertise Reg D securities to anyone, though brokers are supposed to ensure that purchasers are accredited. In other words, the harsh lesson for investors remains the same as it has always been: buyer beware.