When the movie-geek parlor game commences, the populists are usually prone to cite The Godfather or The Lord of the Rings as the greatest cinematic trilogy of all time—even though, let’s be honest here, the third Godfather looks puny and pulpy in comparison with the first two, and that middle Lord of the Rings picture is a lumbering, occasionally ludicrous bore. The highbrows might cite Satyajit Ray’s soul-stirring Apu trilogy, which chronicles the coming of age of a boy in rural India, or Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Three Colors trilogy, a fanciful riff on the symbolic notions of the French flag: liberté, égalité, and fraternité. The debate wouldn’t be complete without at least one annoying person making the case for a trilogy that was labeled a trilogy only after the fact, such as the John Ford/John Wayne “cavalry” trilogy (Fort Apache, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, and Rio Grande).

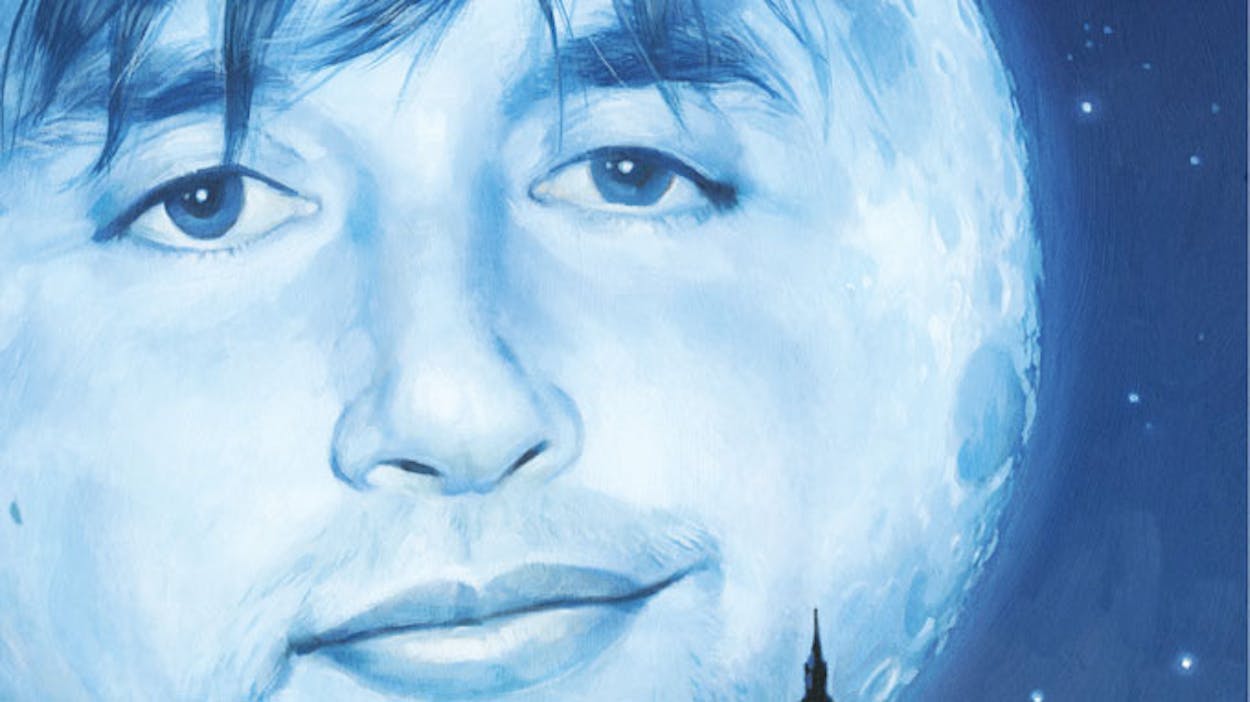

Yet with the arrival of Austin stalwart Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight, which extends the story of lovers Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) that first began in Before Sunrise (1995) and continued with Before Sunset (2004), I would submit that the argument is finally settled. The film premiered in January at the Sundance Film Festival, where it deservedly stole the spotlight from just about everything else being shown. Acquired for distribution by Sony Classics, which will likely push it hard for next year’s Oscar race, Before Midnight will turn up this month at Austin’s South by Southwest Film Festival and officially open on Memorial Day weekend. Clear your schedule and see it the instant you can.

This latest effort doesn’t merely deepen our understanding of Jesse and Celine and treat us to another funny-melancholy consideration of the agonies and glories of romance; it expands our very notion of what a trilogy can be. On the one hand, the Before films function as an almost documentary-like illustration of time’s inexorable passage (the most obvious comparison is Michael Apted’s Up series of British docs, which revisits its interview subjects at seven-year intervals). On the other, Linklater’s trilogy is richly cinematic and quietly groundbreaking: using the same actors and basic structure but employing the tropes of different genres, Linklater has come arguably closer than any director to creating a kind of symphony onscreen. The Before movies are each distinct movements that introduce new themes while hauntingly circling around a set of common ones.

Eighteen years have passed since Before Sunrise, when Texas-born tourist Jesse met Frenchwoman Celine on a train to Vienna and the two fell in love over the course of a long, talky night. Nine years after that, they met again in Before Sunset, when Celine tracked down the now published author Jesse at a bookstore reading in Paris. The idea of time moving too quickly has always been central to these films, and in Before Midnight it hits us with astonishing force in the opening shot of the movie—the once adorably boyish Jesse looks haggard and even a little silly in his hipster Neptune Records T-shirt, like an aging rocker who doesn’t want to admit his moment is over.

At the start of the picture, Jesse is at an airport in Greece, sending his thirteen-year-old son (Seamus Davey-Fitzpatrick) back to Chicago, where he lives with his mother. The parting is especially anxious: having spent the past nine years with Celine—they now live in Paris and have twin daughters—Jesse doesn’t want to miss another moment of his son’s adolescence and yearns to move back to the United States. The only problem is that Celine, who has just landed a new job in Paris, resists. In the car ride from the airport back to the villa where they are vacationing, Jesse and Celine begin another of their winding debates, this one almost fifteen minutes long, shot in an astonishing single take, which culminates with Celine telling Jesse: “This is how people start to break up.” So much for the happily-ever-after suggested at the end of Before Sunset.

By any reasonable measure, these movies should feel repetitive, both visually (with Hawke and Delpy again posed side-by-side in the frame, talking and sometimes walking) and emotionally (how many times can the same characters keep drifting apart and coming back together?). Yet Before Midnight stands apart from its predecessor, which in turn stood apart from its predecessor. This singularity partly has to do with the films’ understanding of the anxieties that plague us in our twenties, thirties, and forties—and how youthful ambition gives way to adult frustration that gives way to middle-aged resignation.

Far more subtle is the way Linklater and Hawke and Delpy—his co-screenwriters—have conceived each of these works. Before Sunrise was, in effect, the fairy-tale romance that reaffirmed our fantasy notions of soul mates and true love (think Moonstruck or When Harry Met Sally . . .). Before Sunset was the romance touched by reality—about two bruised souls searching for salvation—and it unfolded as a kind of race-against-the-clock thriller: Jesse and Celine had only one hour to decide their future before he was supposed to get on a plane back to America. (Linklater seemed to be tipping his hat to one of Hollywood’s great, if vastly unsung, romantic dramas, 1945’s wartime-set The Clock, starring Judy Garland and Robert Walker and directed by Vincente Minnelli.) Before Midnight, finally, is the post-romance romance that shows us how frustration and resentment build up over the course of any long-term relationship. Back at the villa, Jesse and Celine have a late lunch with friends and then make their way to a hotel to enjoy a rare evening alone. Alas, this time the chatter devolves into a lengthy, bitter argument that threatens to destroy their union. The result is less a classic Hollywood love story than a bruising melodrama of marital discord, like Ingmar Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage or Alan Parker’s Shoot the Moon.

There is so much to praise here that it’s hard to know what to single out. If Before Sunset ultimately belonged to Hawke (Jesse’s monologue about falling out of love with his wife was especially devastating, perhaps because the actor and his wife Uma Thurman were breaking up while he was filming the movie), Before Midnight returns the favor to Delpy. Playing a woman who never quite knows what she wants, she serves up a series of quicksilver emotional flips that are exhilarating and often hilarious to witness. There are also the echoes that Linklater has layered throughout—references to the pinball game that Jesse and Celine played in the first film, or to Jesse’s beard, which Celine remembers as having once been reddish but which is now going gray—that gently link the three films.

And, of course, there are the conversations, about subjects previously touched upon (the challenge of living in the moment, the differences between the genders) and entirely new (Celine recounts an entertainingly bizarre story about how her father used to murder kittens), conversations so smart and honest and vulnerable and universal that you feel like they could be your own. These conversations connect the Before films all the way back to Slacker, the ultra-chatty movie that launched Linklater in the early nineties, and bring his career full circle.

This new film ends on a slightly ambiguous note—the greatest trilogy in film history may yet end up being a tetralogy, pentalogy, or hexalogy. For now, though, Before Midnight cements Richard Linklater’s status as our greatest celebrant of the power of talk: as aphrodisiac, as intellectual stimulant, and as salve for a broken heart. No disrespect to the laudable likes of Dazed and Confused, School of Rock, and Bernie, but these movies are his masterpieces.