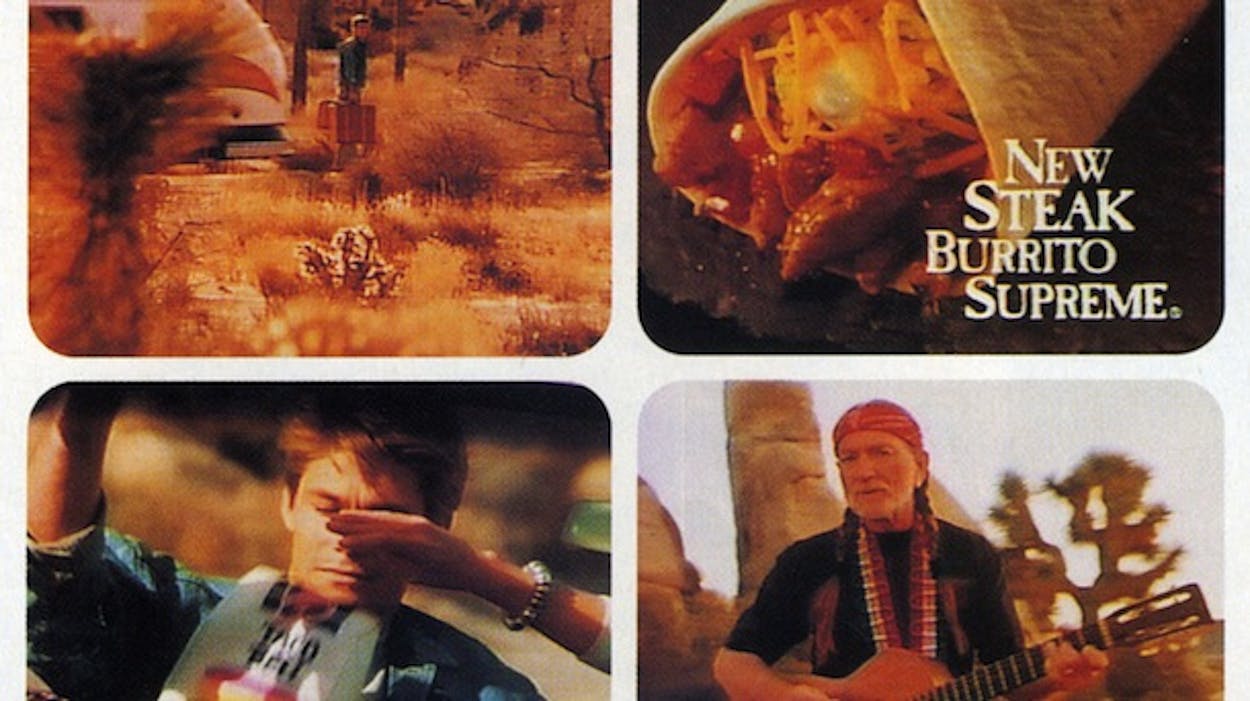

EDITOR’S NOTE: Like all good Texans, we did not quite know how to react when favorite son Willie Nelson showed up on our television screen as a pitchman for Taco Bell. The ad—titled “Rose Tattoo”—was tantalizing, but its ultimate meaning seemed elusive. In order to delve deeper into Willie’s complex message, we contacted Stephen Harrigan, the Bum Phillips Professor of Literary Theory as Creosote College, Vista de Nada, Texas. Professor Harrigan has obligingly viewed the commercial through a deconstructionist-historicist-Marxist lens and offers the following exegesis.

Almost from the moment of its first airing, Willie Nelson’s Taco Bell commercial, [The Woman with the] “Rose Tattoo,” has been regarded as one of the most intriguing texts of the post-deconstructionist era. A lively scholarly debate, however, has arisen over what a philosopher Merleau-Ponty, had he lived long enough to see the invention of the zest taco melt, might have termed the piece’s thisness (eccéité). Is it, as Ignosz Delerue suggests, a searing indictment of European imperialism? Is it male cri d’horreur about impotence (note the recurring references to “soft” tacos), or does it suggest castration itself (as reflected by the early disappearance of the bus/phallus from which the hero disembarks)? Or finally, as Jacques Derrids would maintain, is the text itself utterly meaningless, an incidental by-product (sous-produit) of Nelson’s overriding compulsion to make enough money to pay off his IRS debt?

On the surface, the narrative is simple. An unnamed traveler is shown arriving in an inhospitable desert landscape, a terrain familiar to viewers of earlier Taco Bell commercials featuring Little Richard and Hammer (see “Running for the Border: A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Taco Bell Universe,” by C. Jacques Poularde, Cahiers d’Offuscation, November 1991). “He got off the bus at the border,” sings Nelson of this traveler, “when up drove the woman with the rose tattoo.” Three times the Woman (who drives a magdalen-red convertible) tempts the Traveler with a variety of 99-cent steak tacos, and three times he succumbs. At one juncture, she pointedly drops a bag containing a Steak Burrito Supreme into his lap, eliciting a response from the phallo-centric protagonist that may be an expression of jouissance or puissance or both.

The battle for sexual hegemony illustrated in the burrito incident is plainly mirrored by a larger context, i.e., the European domination and desecration of the native peoples and landscapes of the New World. Is there a more powerful symbol of rapacious imperialism than the taco? In the empty shell of corn we see the sad defeat of the maize culture that once flourished in the American Eden. Within in the taco reside ground beef, representing the speciesistic carnage perpetuated upon the bovine community and, by extension, all nonhuman life-forms. The shredded lettuce that so cruelly garnishes this heap of mangled flesh can be nothing other than the felled trees and uprooted prairie grasses of a once-verdant continent. And then, of course, there is cheese, the ultimate expression of the dairy mentality, in which the very mother’s mills of unsuspecting cows (les vaches qui ne soupçonnent rien) is siphoned off to satisfy the needs of the predatory human appetite. The onions that often crown a taco testify to the tears of the ravaged earth as she wails for her lost innoc(ess)ence. (For a ground-breaking work on onions, see Miranda Portman-Blodgett’s “The Crying Game: Onion as Metaphor/Metaphor as Onion,” Diacritical Digest, June 1989.)

Willie Nelson himself, playing his guitar and singing as he wanders through the commercial, is a more ambiguous figure. With his long pigtails, his headband, and natural fiber clothing, he certainly evokes the aboriginal ethos, though a Christological interpretation is perhaps even more apt. The text subtly reminds us that Willie Nelson was not the first bearded man to wander in the desert, and indeed we need to look no farther than the contorted Joshua trees in the background for a tantalizing reference to the Crucifixion.

And yet Nelson’s wry, detached presence presupposed a darker level of meaning. His easy tolerance of the appellation “Woman with a Rose Tattoo” could be interpreted as a tacit endorsement of ritual scarification, but as a viewer weighs the imagery it becomes apparent that the only things being endorsed here is a 99-cent taco. Indeed Nelson, the godlike figure of the text, is plainly indifferent. He is just walking through the commercial picking up a check. The frisson the viewer feels upon this realization is not unlike the sensation s/he feels when contemplating the void itself. In this, powerful work, Willie Nelson courageously confronts the gnawing doubt at the heart of all post-modern thought. There is no God, his commercial boldly informs us, only the Steak Burrito Supreme.

- More About:

- Music

- Film & TV

- Television

- Willie Nelson