This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When asked the secret to her extraordinary social success, Twinkle Bayoud, wife, mother of two, and until recently Dallas’ most prominent realtor, mentions her acquaintance Adnan Kashoggi, the controversial Saudi Arabian financier. “My father always taught me to drop my money on the marble floor, not the carpet,” Kashoggi once said. “Drop it where people can hear.”

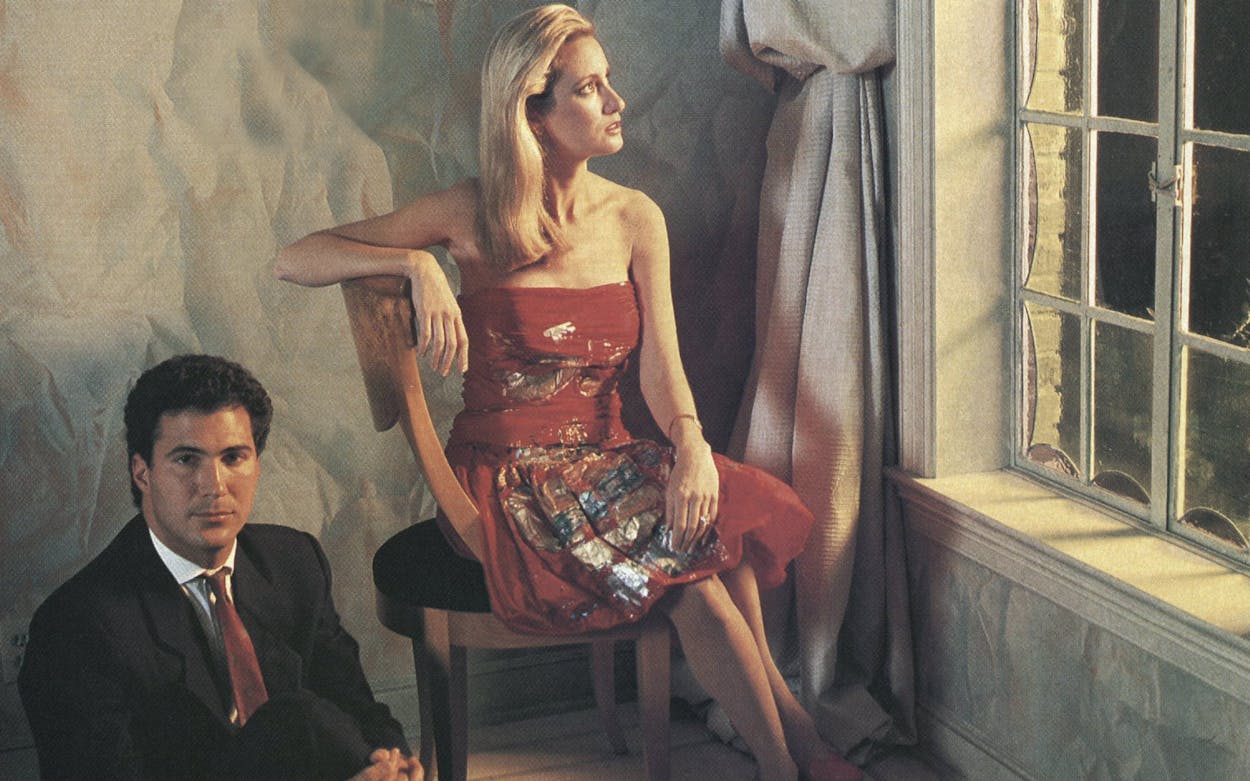

That lesson has served Twinkle well. By making a splash, she and her husband, Bradley Bayoud, have, in a manner like hardly anyone in Texas, made the leap from being local socialites to national celebrities. Born to position and privilege, they quickly rose to the top of the Dallas social heap. They made a fortune in real estate by the time they were in their mid-twenties; then, with style, luck, and a publicity agent, they captured the attention of the national press. Overnight, they became Names, citizens of that rarefied world that exists in social columns. They became the new Texans to Hollywood, New York, and Europe. They fly from coast to coast, from party to party. In Hollywood they are the darlings of social lion and society columnist George Christy. They count actress Catherine Oxenberg and movie producers Roger and Julie Corman as their friends, and such luminaries as Allan Carr, Robert and Rosemarie Stack, John James, Joan Collins, and Jacqueline Bisset come to parties to meet the young couple. In New York, where they have rented a loft in SoHo, they mix art and society, running with artist Andy Warhol and Fred Hughes, one of the more stylish men in America and the president of Interview magazine. The Bayouds travel so much and appear in society columns so often, they give the impression of ubiquity.

Their life looks so enviable it inspires rumors that it can’t last. The Bayouds are almost a case study, with lessons of their own to teach. Imagine the life you want; the Bayouds are firm believers in the power of positive thinking. Seize the coin so that you have it to drop. Organize your home and your domestic staff so that you will have the maximum amount of time for social pursuits. Study the art of celebrity. Make your clothes and your home the cause for envy and attention. Hire the best press agent in town. When luck brings that useful celebrity into range, befriend and entertain him lavishly. Build momentum by working the connections between the people you know. After all, as anyone who is anyone knows, there are only about a thousand people in the world, and they all know each other.

The Gold Coin

It’s Monday morning in Dallas. Beyond the wrought-iron gates of the slate-gray Tudor house, there is the entry hall with bleached oak floors and faux marble woodwork. A glance into the elegant dining room reveals a table designed by Dakota Jackson, hand-painted wallpaper, and Zichele chairs. In the living room legions of tiny overhead spotlights illuminate a variety of avant-garde art objects and furnishings that summon a litany of designer names. Bradley Bayoud appears from the family room wearing a slate-gray Italian suit. Twenty-nine years old, he looks as if he stepped from the pages of Gentlemen’s Quarterly. He has slick jet-black hair, Mediterranean features, and lively dark eyes. When Twinkle comes in, wearing a flowing royal blue skirt and earrings that resemble Slinkies, she looks a bit like the young Eva Perón. Her streaked auburn hair is pulled straight back from her rather long, angular face. At 28, she is the veteran of millions of dollars in real estate sales.

A silver tea service is brought in. After Twinkle pours, she turns her attention to the subject at hand: the press. Magazines and newspapers are full of pictures of the Bayouds—pictures that are the epitome of rich Texas flash. Twinkle and her father leaving the family plane. Twinkle in Bradley’s arms in front of Brad’s Grand Prairie building. Tiny Twinkle in diamonds surrounded by five beefy Dallas Cowboys.

“I tried to wear everything American,” she says, pointing to a picture where she’s adorned in a sequined Stephen Sprouse that clings to her body like a pink lemonade–hued reptilian skin. Another features her posed before the Infomart in an ink-blue sequined Fabrice.

She flips through the pages of the French magazine Madame Figaro and finds the feature article about her. I admire the photographs, then I ask about the extraordinary amount of press coverage she and Bradley have had.

“But perhaps you’d like to see the house,” says Bradley.

Touring the house is a Bayoud family ritual that takes the visitor through every square foot, including the bedroom. In a very real sense, this is the gold coin dropping, the symbol of their success. Downstairs, Bradley points out the Vernon Fisher and the Robert Rauschenberg, along with work of his own and that of less famous artists. Designed to be a backdrop to the art, the house, along with everything else in the Bayoud world, is for sale—if the price is right. In the case of the house, it’s $2.9 million. “Selling my homes is an occupational hazard,” Twinkle says when I mention the real estate sign in the front yard. “But when it comes time to buy something, Bradley acts as bargainer.”

“People think we just go around spending money like it’s in a tap that we just turn on anytime we want,” Bradley comments. “But we’re like anybody else. We may have some money because we’ve made it. But we’re not like Perot, or even close to that kind of people. . . . I negotiate with everybody. I’ve got some Lebanese in me, and I barter.”

From the first floor we climb the staircase to the guest room, which has probably received more press than most small museums. It’s a large room, the walls painted with silver lacquer, simply furnished except for two art deco beds designed by Radio City Music Hall designer Donald Deskey. “They’re expensive when you think about beds,” Twinkle says, standing between the sleek black beds. “But they’re collectibles. It’s American art deco, and they’re documented in this book on Donald Deskey. We had seen them in New York. We were buying things for the house, and we were trying to stick to our budget. Bradley wanted them, felt they were too expensive, and tried to negotiate with [New York art dealer] Alan Moss. And Moss was like, ‘How dare you want to negotiate on such a valuable piece of furniture!’ He just said, ‘I won’t sell them to you.’ So I kind of stepped in and surprised Bradley with them. I couldn’t talk Alan Moss down either. I just gutted up and paid the price.”

Next comes the Bayoud bedroom, home of their famous king-size bed by interior designer Donghia. The Bayouds attribute much of their success to dreaming or, more specifically, to The Power of Positive Thinking. “Fifty million people have insomnia,” says Twinkle. “And especially our generation—we all work, work, work. Tension, tension, tension. But having the big king-size Donghia bed, we’ve really spent a lot to have a really properly constructed bed. Donghia just died. He was a very important interior designer, did all Ralph Lauren’s houses forever. We were down at David Sutherland’s picking out some other furniture, saw the bed, and just fell in love with it. When they said the price, I was just, ‘Ahh!’ It was like a ten-thousand-dollar bed. Of course, you do have leather piping on it, and a silk coverlet. I mean, the material’s expensive.

“When I was a real estate agent, I was always showing houses in my dreams. Just working through problems. Instead of staying up all night worrying about problems, I tell my subconscious to work on them, and I will consciously erase my mind and go to sleep. And I usually end up saying the most brilliant thing.”

The road to sleeping on a $10,000 bed, however, has included a few ordinary Posturepedics. After the tour we retire to the living room to sit upon Michael Graves’s bird’s-eye-black chairs and listen to the story of Twinkle Bayoud’s beginnings. Born to privilege and steeped in Highland Park charm, Twinkle is the youngest daughter of George Underwood, a postwar builder who developed the Dallas suburb of Richardson and who, for a while, owned an interest in the post–Clint Murchison Dallas Cowboys. Twinkle was christened Norma Carol Underwood, but after her father held his infant daughter in the air, admired her chocolate-brown eyes, and called her Twinkle, the nickname stuck. Her father’s strong arms and money, however, did not immediately toss Twinkle to the heights of her present stardom. Instead, she didn’t get a family dime. If you listen to Twinkle, her ascent was something akin to climbing the Matterhorn in one of her delicately beaded Fabrice evening gowns. The story starts, as many rich young women’s stories do, with Daddy.

“Daddy was a postwar builder, and he had tremendous success in creating suburbs, speculating in land, and building shopping centers. He was on the city council when I was five. He would be good for that new show The Start of Something Big. He started with five thousand dollars borrowed from my grandfather and turned it into his fortune.”

She takes a sip of tea from a bone-china cup that features a pack of hounds chasing a fox around the brim. “I look back at home movies, and he’s got these suburbs of houses, and all the people are lining up to look at them. He got great press in his time. He’s even got a trash can with his press glued around it that Mother made for him.”

Twinkle’s own notoriety began when she was a sheltered Hockaday girl and Bradley was a student at St. Mark’s School for Boys. “Twinkle always had this ability to create this aura about her,” says Bradley. “She was like Edie Sedgwick. She has that same kind of personality—everybody just has to be around her.”

Each evening kids crowded into Twinkle’s parents’ Highland Park house as if it were the corner drugstore. Of all the boys who showed up at Twinkle’s door, Bradley Bayoud the intellectual would win her heart. “Bradley came walking up one day, and I remember he looked so interesting to me,” Twinkle says. “I just saw right through to his soul. I remember exactly what I wore. I don’t know who designed it or anything, but it was this pink dress. I slapped him on the second date. He was too forward—a little mover. I wouldn’t do anything but kiss him for two years.”

Her early romance revealed, Twinkle suddenly seems to awaken from her high school memories. “This is so boring!” she says. “This is like taking out the high school annual.” She looks at the tape recorder. “Have you got enough stuff for a story?”

Well . . .

She nods her head knowingly. “You need more stuff, right?”

She offers another revelation. “I was really kind of a spoiled brat. I came so late that I was the baby of the family. It was almost like having five adults to pamper me and take care of me. It was the time when my parents came into their greatest affluence, so it was easy to buy me toys. That really attached love with possessions. I was getting so many things. I got a 350 SL when I was fifteen and had my license that let me drive only when somebody else was in the car. I used to drive around with my houseman to the record store. And I’d go in and buy every record you ever heard of. I’d write a check, signing ‘Twinkle Underwood.’ They’d ask for a license, and I’d go, ‘No, I can’t drive yet.’ ”

Her bank account, however, supplied all the credentials that Twinkle needed. It was flush with an average of $10,000—the windfall from an early investment in Hereford and Charolais cattle. “My father tried to teach me the value of money by getting me into the cattle business. And it did real well. He took me to the bank, taught me how to get a loan, and we went out and bought some cows. I really had no concept of money. I think I borrowed two thousand dollars. So when the cows started making money, I went in to pay off my note. And the checks kept coming.”

The turning point came when Twinkle was sixteen. “What set it off was that we were going to the ranch, so I couldn’t go out unless somebody brought me back to Dallas that night. Bradley was having a party, and I knew I would have to miss it. I was really angry. Of course, I couldn’t stay at home by myself, so I went to the airport with a friend and her boyfriend and took off. We went to Hawaii. It would have been London, but I didn’t have a passport with me.

“The whole thing was really quite horrible. We took the family Wagoneer because I didn’t want anything to happen to my Mercedes. On the way to the airport my friend reached into her purse to get something and cut her finger on a razor blade and wiped it on her purse. Some of it got on the car, so when they found the car in the parking lot at Love Field they discovered blood in it. It was really horrible, really horrible. Everybody thought that we had been kidnapped.”

But for Twinkle Hawaii was fun and sun. “We went island-hopping. It was really neat to go over and see where the locals lived. It was like going to the jungle. I had pulled three thousand dollars out of my account. I didn’t tell anybody where I was going, because I knew if one person knew, the pressure would be on them.”

Driving through the jungles and sunning on the shores, Twinkle tasted her first freedom outside the confines of Highland Park. After a few weeks, however, when she was running low on cash, the sun set on her vacation. “It was something out of Miami Vice. Oh, God, it was just the worst! I got robbed and was out of money; I couldn’t work because I wasn’t seventeen. And you know, I’m just not the type to go and sell my body on the streets. And I can’t live without money. So I called home, which took a lot of guts, and when I got home I was a completely different person.”

“But the robbery,” I say. “Tell about the robbery.”

“Oh,” she moans. “Oh, God. We moved into a place where you pay by the week, but it was still pretty nice. But we had all of these scumbuckets following us around. Anyway, this guy knew where I would be walking, and I got jumped. These two kids my own age—Hawaiians—had a knife, no gun. If they’d had a gun, I would have been killed. They pushed me into a car, and we were driving way far away from Waikiki, and I started crying and tried everything to get their pity. I mean, I was sincere! It was like, ‘Please, please, please! I don’t have any money to live on!’ Knowing I had some money in my back pocket. I could see this big rape scene. Here I was sixteen. I was still a virgin, still naive. And I mean, these guys were real scummy. I mean, we’re talking serious trash! But when we went around a turn, I opened the door and bailed out. One of the hoods ran after me, stabbing me in the stomach and the leg. . . . I kicked him in the balls and paralyzed him for a second. I started screaming, and the guy’s friend got scared and called for him to come back to the car. Nobody in the neighborhood came out of their home. I walked to a gas station and called a taxi. I came home soon after that. I saw what the rest of the world was like and decided I didn’t like it.

“Then Hockaday wouldn’t let me back in,” Twinkle says. “I’d messed up all my hours, and they were real concerned. And I’d kind of started this thing. You know, I’ve always been a leader. After I ran away everybody at Hockaday started running away. And all of the parents were real freaked out. They all started to blame me because everybody else started doing it. They would go to Colorado, boring places. Some of these kids who ran never made it back. I mean, they made it back, but not mentally. They fried their minds.”

Students of Celebrity

As Twinkle speaks, her household hums quietly in the background. This is the way of all proper Dallas homes, where, when visitors are present, the sounds of rush, worry, or crisis are seldom heard above the white noise of a well-functioning dishwasher. The Bayoud home seems to echo constantly with the sound of things going well. The key is proper staffing, of course. The Bayouds’ staff includes a maid and a nanny from Denver’s prestigious N.A.N.I. school. The nanny is the children’s social secretary, sorting out the party invitations and routing the two girls in the proper direction. Mommy, however, is constantly on call: driving Alexis and Natalie from Hockaday to dance lessons while keeping in touch with the office via the telephone in her Mercedes. Daddy is the artist with the children, playing the piano and telling them a never-ending series of stories, which he calls “The Continuing Story of Alexis and Natalie.” The Bayouds take their daughters to McDonald’s, to Showbiz Pizza, to the bowling alley, and, with nanny in tow, on their jet-set escapades.

Bradley Bayoud moves in and out of his wife’s conversation, just as he moves in and out of the living room on this interview afternoon. On the surface the Bayouds seem to be a perfect team—combining Twinkle’s excitable brashness with Bradley’s calm and cool. “We saw qualities in each other that the other was lacking,” says Bradley. “We were like two pieces of a puzzle.”

The son of a surgeon who invested in real estate, Bradley knew from the beginning that he was going to be something—an actor, an opera singer, or an artist. He evolved into what he calls a reading-writing type of hippie, and attended Andover, then the University of Texas and Southern Methodist.

Bradley and Twinkle showed a marked interest in celebrity at an early age. Throughout their college years, they each carefully studied the fine art of celebrity. When they were students at SMU, before they knew Andy Warhol, they sneaked up beside the artist at an exhibition. Bradley posed next to Warhol while Twinkle snapped a photo.

What first attracted Twinkle to Bradley was that he had something that she didn’t: an intellect. “After high school I went to Pine Manor for a year. Or Pine Mattress,” she says and laughs. “Bradley’s sister had gone there, and I thought it would be neat to have an East Coast experience and not have to work hard. I hated the school. I couldn’t go anywhere. It just had the worst reputation, and I didn’t realize that. It was ’75 and the curriculum was so weak, so easy. You know, it was your typical rich, dumb girls’ school. And I thought it was terrible.”

Twinkle left to attend UT, then followed Bradley to SMU. In 1977 the teenage sweethearts married and set out to become famous artists, Bradley as a painter, Twinkle as a photographer. After Bradley’s graduation in 1978 they drove to Maine in a graduation present—a BMW. Bradley enrolled in art school at Skowhegan, but art soon surrendered to business because of a lack of money. The Bayouds returned to Dallas to find jobs in the business world. Then business surrendered to boredom, and they moved to Washington, D.C., where Bradley got a job as an aide in the Texas State Federal Relations Office.

“I was pregnant with Alexis,” says Twinkle. “And my father, being a typical Texas father, was not at all pleased to have me go off with my first child up to Washington. Well, then we communicated, and my parents came up when the baby was born and everything was fine. They were under a lot of stress. Mother had cancer, and I didn’t know it. So all of their behavior I took real personally. Then Bradley’s position was up, and we were out of money, so we moved back down here. He was really trying to make it as an artist. He had been working as an artist at the time. And the baby. It was your typical story.

“Since we were kind of stuck, what do we do? I was twenty-two. Bradley wanted to get his M.B.A. We had a little money we had saved up, and with help from Bradley’s parents we put a down payment on a house. We immediately kind of gravitated to real estate. And my father was just livid. ‘You don’t even have a job,’ he said to me. ‘How can you buy a house?’ He didn’t talk to me for a year.”

To help with the mortgage payment, Twinkle applied for the mundane job of bank teller at Richardson Bank and Trust and was promptly hired. Of course, it didn’t hurt that her father owned the bank and that she was a stockholder. “I didn’t want to ask my father for money to finish my education at SMU, so I went to UT-Arlington. That way I could work at the bank at the same time, which really got to be fatiguing.”

The Bayouds were down but far from out. Nine months after buying the house, they sold it for $200,000—reaping a $90,000 profit. But the best was still to come. Bradley would find his Medici in the form of a Hunt, and Twinkle would be inspired by her dying mother.

Hating her job as a bank teller, Twinkle cast her eyes toward her sister Helena’s real estate firm. “I talked to my sister,” Twinkle says. “I asked her, ‘How much money does a real estate agent make?’ She said, ‘If you’re good, about twelve thousand dollars a year.’ I thought, ‘That’s just a little bit more than what I’m making as a bank teller.’ I was taking home about six thousand after taxes. So I went in, my first year, and I made sixty thousand dollars.”

With the income came the pride and support of her family. But Twinkle’s father wasn’t alone in his pride. Her chief ally in her early years was her mother, Nancy. “When I first started selling with Helena, Mother took me out and bought me two businesslike suits at Lou Lattimore. And I was just barely pregnant for the second time. It was 1980. I remember they were seven hundred dollars together. Mother got the bill; she was buying it for me. She wanted me to have the right look, a good presentation. Later she was kind of out of it. But she was the motivating force in my leaving Helena and starting my own company.

“Helena’s eight years older than I am. She got married briefly when she was twenty. Got a divorce when she was twenty-one. And Mother and Dad were no doubt behind her going into real estate. They really never thought she would get married again. So Helena gets married when she’s thirty-two, and Helena gets pregnant, and I’m starting to come off as this super whiz kid. And Mother and Daddy are thinking that the best thing for Helena would be to stay at home with her husband and her kids. They’re trying to get Helena out of real estate, and they’re trying to help me buy her out. And Helena didn’t want that. She didn’t want to give it up.

“But everything was pretty amicable. Mother was on her deathbed, and this was something that she wanted. We were really close. And I felt like if I kept her on a positive note, she was gonna fight this. It really was dramatic. I mean, she was in her robe. She had no hair. She was in this little hat thing. I’m in her library, and she’s in Daddy’s big easy chair because she’s tired of being in bed all the time. I’m sitting on the floor and she’s holding my hand, telling me I’ve got to do this. She was being so insistent, because she felt that she didn’t have very much time.

“And she led me to believe things like: ‘He who has the gold makes the rules, and I’m going to leave you all the gold.’ When she died she didn’t leave me a penny! She was always saying, ‘You have to go out and do it on your own.’ Everything, for tax purposes, went to Daddy.”

The Magic Dress

Twinkle made sure that they had that necessary ingredient to success—money. The company that Twinkle created with $50,000 borrowed from her father—Bayoud and Bayoud—ushered in the socialite era of Dallas real estate. Twinkle’s agents wore diamonds and silk just as Century 21 agents wore the trademark yellow jackets. But the company was different in other aspects. First, there was the name. The double Bayoud name was a sign of respectability, a law firm–style name for another novice real estate company.

Twinkle proved to be an inspiration to her sales force, much as she had been to her fellow students at Hockaday. She was a role model, an arbiter of fashion. When she voiced intentions to move up from her small 380 SL, big Mercedes became the rage among Bayoud realtors. When the agents would come to the Bayouds’ house for morning sales meetings, Mercedes, Cadillacs, and other expensive imports would glide to a halt in the circular drive. The women—the sort with Louis Vuitton bags, Porsche sunglasses, gold-nugget Rolexes, David Webb knockoffs, and real stones from Mama’s lockbox—would parade into the house, their designer shoes tripping over the oak floors. Twinkle, in only a few moments, could pump the women with passion for the trappings of their trade: closings, escrow accounts, home tours, cute condos, and haughty haciendas.

Twinkle was a real estate natural, but something was missing, and that was publicity, fanfare—the sound of gold dropping on the marble floor. “To have a competitive edge, you have to have tenacity, honesty, integrity,” Twinkle says. “And then the press gives you that extra added fizz.” Several months before Twinkle’s business opened in September 1983, she had a stroke of blind luck—being at the right place at the right time in the perfect dazzling dress.

“That dress,” says Twinkle.

“The magical dress,” Bradley says and laughs at the memory.

They tell the story of the dress with relish. The dress achieved its own celebrity on June 13, 1983, when the eyes of Dallas–Fort Worth society swept across Fort Worth’s Ridglea Country Club at an amazing spectacle: an outrageous debutante party along a recreation of Route 66. On this evening, as 1500 black-tied guests sipped Moët Chandon and walked on the raised, lighted highway through sets depicting the highway’s trail from Chicago to Los Angeles, the photographers caught Twinkle in mid-party pose, peeking over her shoulder to reveal a back covered only slightly by a beaded electric guitar, the crowning piece of a Karl Lagerfeld original.

Twinkle Bayoud had arrived.

The dress was a birthday gift from Bradley, selected on a trip to the Lou Lattimore boutique and given to Twinkle earlier that summer as they flew from Dallas to Kerrville on her father’s plane. The guitar dress played an important part in introducing the Bayouds to the spotlight. The first wearing—at the Cowboy Art Museum in Kerrville—caused quite a stir. “I wore it to that Route 66 party, and I wore it later at a party in California where I met Hollywood Reporter columnist George Christy. Bradley gave it to me. We’re flying . . . now, my mother had cancer, and I’m successful and everything’s, well. . . . So we’re flying to my father’s club in Kerrville. It’s my birthday, and I hadn’t even thought about my birthday because I’m working all the time. On the plane Bradley gives me this dress, the guitar dress. So here we are, in Kerrville, Texas. I put it on, and it’s a little bit too tight. Or I feel like it’s really kind of revealing. I go, ‘Mother, this dress is too tight. What should I do? Bradley really wants me to wear it, and I think it’s kind of risqué.’ Mother was president of the Dallas Woman’s Club, most conservative, the perfect lady. Anyway, she says, “Bradley gave you that dress for your birthday, and you wear it.” She loved Bradley. At this point she is just goo-goo over him. She thinks he’s a Renaissance man and hung the moon.

“So I wear this dress, and every time I walk it kind of edges up my hips. It’s so tight. And it was so funny. I’d walk, and everybody would follow me. It really had an impact. Gerald Hines was there, everybody in Texas was there. Then I took it back to Lou Lattimore’s and had it let out so it wouldn’t be so tight. It was one of a kind. Jann Kelso, the society editor at the Dallas Morning News, saw it at the Route 66 party, and she saw us out in California. That’s when she wrote, ‘Twinkle wore the now-famous guitar dress.’ ”

Twinkle wore the dress to the Texas Meets Hollywood party in Los Angeles, where budding Texas film industry leaders met their Hollywood counterparts at Caroline Hunt Schoellkopf’s newly refurbished Hotel Bel-Air. At the party the Bayouds caught up with Roger and Julie Corman, friends the Bayouds made while serving on the board for the Dallas Film Festival. The Cormans introduced the couple to George Christy, telling him that they wanted him to “meet somebody who’s really Dallas, really Texas.” Twinkle didn’t realize the columnist’s power in the movie trade. But when she asked him to join her and some friends for a late dinner one night at Spago, Christy accepted. A few days later, on August 3, 1983, in his column “The Great Life,” Christy wrote: “Twinkle Bayoud’s sparkle-plenty dress by Karl Lagerfeld was the talk of the evening.”

“Later, when we were going out to California for Alexis’ birthday, to take her to Disneyland, we told Christy we were coming, and he said, ‘Great, I’m going to throw a party for you that you’re not going to believe,’ ” Twinkle recalls. “He was going to do this party anyway. I thought it was really neat. Everybody was there. Brandon Tartikoff of NBC and his wife, Lilly. They’re wonderful, so sweet. Allan Carr, Robert and Rosemarie Stack, John James. Even Joan Collins showed up. I wore a pink Bernard Perris. Bradley was sitting next to Jackie Bisset. You know. He got a good giggle out of it; she was really funny. And Alexander Godunov. You get to a point where—I don’t know—you talk on two different levels. There they are, and there’s the movie star you’re used to seeing on the screen. After a while you just forget all that.”

But when the party was over, it was the new kids who got the ink. Back in Dallas the social drums were pounding for the opening of the new real estate firm, Bayoud and Bayoud. Twinkle had hired Julia Sweeney of the public relations firm Callas, Foster, and Sweeney. Press releases were written. Columnists were advised. Media were alerted. Julia did her job well. When reporters called her for possible subjects for an upcoming story on working mothers, Julia referred them to Twinkle. If the story was about businesswomen on the rise, Twinkle was recommended. If the story concerned a husband-wife business team, Julia sent them Twinkle and Bradley. The press attention had its four-color climax just before the star-studded opening for Bayoud and Bayoud at the Mansion on Turtle Creek. The new “Unique” section of the Sunday Dallas Times Herald devoted its first cover to “Twinkle Bayoud: The Life of a Rising Social Star.”

Bayoud and Bayoud represented Real Estate as Theater, with its two dozen Ewing-style women on the real estate run. Bayoud and Bayoud advertisements were placed in the society section, not the classifieds. Oversize pictures of Twinkle’s agents ran in the ads. Even the aluminum For Sale signs were different, with two B’s meshing in blue and pink, “like the cracking of an egg, the breaking of a new idea,” Twinkle says. And the Bayoud and Bayoud parking lot was so upscale that one newspaper reported that it “looked like it gave birth to little two-seater Mercedes.” Another noisemaking center of attention was Bayoud and Bayoud’s International Division, which was born with the listing of a lone Swiss residential development and quickly amassed a $200 million European portfolio. “Once the word got out, people started bringing me properties from all over the world,” says Twinkle.

When Nancy Underwood died on September 9, 1983, Twinkle Bayoud was on her way to becoming a real estate phenomenon.

To Revolt and Shock

“It comes as a shock, doesn’t it?” asks Bradley, standing in a back room of the headquarters of Bayoud Interests, his downtown Dallas development office. Outside are the normal trappings of a business office, but the back room is totally devoted to Bayoud’s art.

Bayoud the artist is not at all unlike Bayoud the Developer. He exudes a convincing sincerity, a feeling of doing everything with great pride and passion.

“Usually I don’t let anybody back here,” he says, showing his work: giant oil paintings of wild-eyed, surrealistic characters, shapes, and messages. One features a woman with hands raised toward the heavens, raving beside a lifeless couple sitting at a table in a bar. It is called They Lived Until They Died. Another, entitled A Singing Group, features a canvas covered with a doll’s head, a 45-rpm record, lollipops, plastic oranges, and the cryptic message “Give Us Our Breakfast Juice!” A third, Catshow, pictures a cat having an art exhibition. Another is a portrait of producer David King, who prepared a profile of the Bayouds for Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

“A lot of people look at it and say it’s neo-expressionism,” says Bradley. “I call it a cross between fauvism and German expressionism. My stuff used to be more fauvist. Now, it’s more expressionist. It’s like giant doodling. Most people doodle while they talk on the telephone. I put on the speaker phone and paint away.” He motions to his suit. “And I wear this while doing it.”

Bradley talks in a steady stream of anecdotes, stories, facts, and soliloquies. Central to all of that is his view that a building is no less an art form than Warhol’s photo silk screens, Spielberg’s films, or Jean Michel Basquiat’s paintings. Not only has art been an inspiration in business, but it has also opened doors to a rather racy social life in New York. Bradley and Twinkle made an important connection when they met Andy Warhol in 1984. They had gone to an opening of his prints at the Delahunty gallery in Dallas. At a dinner afterward, gallery owner Laura Carpenter seated the Bayouds next to Fred Hughes, Warhol’s business manager and the president of Interview magazine. During the next six months, Hughes called Bradley and took the aspiring artist under his wing, introducing him to Warhol. Through Warhol, Bradley became reacquainted with gallery owner Mary Boone and met graffiti artist Keith Haring and other luminaries of the New York art scene.

“Andy Warhol is one of the most important artists of the twentieth century,” Bradley says. “It’s something I can tell my children. ‘I knew Andy Warhol.’ It’s like I knew Picasso. I would love to sit down with Steven Spielberg. He’s changed film. That’s what I’d like to do with development. Advance it. Make it better. Make buildings better. It’s been the same for fifty years. Any great artist in history has always shocked and revolted!” he says, leaning forward in his chair.

Bradley was a rebel from his beginning in the development business, but he was a rebel with power. While studying for his M.B.A. at SMU, he went to work in the small Bedrock Development office of his brother-in-law Ward Hunt. Bradley started as an intern for Hunt, and within three months he was named president of the two-man, one-secretary company. Hunt owned 450 acres in a gravel pit in barren Grand Prairie on the Trinity River flood plain that he planned to cut up into parcels and sell for warehouse use and garden offices.

Bradley persuaded Hunt to conduct a market study on the property, and the study indicated that the site had potential for a major mixed-use development similar to the urban center at Las Colinas. They looked at the numbers and agreed. That was about all Ward Hunt and Bradley Bayoud agreed on. Bayoud wanted an architectural sculpture garden. Hunt wanted a nice, conservative development, nothing too tired, but nothing that would appear flaky before the business and financial community.

Riverside was planned to be a colossal billion-dollar complex of 16 million square feet, including office space, two hotels, a country club, a golf course, more than 100,000 square feet of retail space, and one thousand condos. Its first two buildings were compromises of both Hunt’s and Bayoud’s architectural standards. After a master plan was developed, Bradley played a large role in the design and construction of an art deco office tower at the development. The building was a financial success—50 per cent leased six months after opening—but the Hunt-Bayoud era of Dallas development was short-lived. The breakup began when Bayoud started plotting Riverside’s retail center. Again, Hunt envisioned a traditional center, like Highland Park Village. Bayoud saw the project as a chance to redefine the American shopping center. To commit his vision to paper Bayoud called upon one of America’s most avant-garde architectural firms, Arquitectonica, a young Miami-based firm known for its brash designs. What the architects created was an eclectic collection of architectural forms. Bayoud named the twelve-building retail plan Planets, but the project never got off the ground. In 1984 the Bayoud-Hunt relationship dissolved, and Bradley established a new development firm, Bayoud Interests.

Immediately, he found a new project, a triangular corner across the street from another Hunt project—Caroline Hunt Schoellkopf’s mammoth Crescent, a multiuse development of Texas romanticism designed by Philip Johnson with Dallas’ Phillip Shepherd and Partners. Bayoud’s site was significant because of the buildings that would share its skyline: Trammell Crow’s mammoth LTV Center, the new InterFirst building, which commands nocturnal attention by lighting up the sky with miles of green neon, and the miscellaneous glass boxes, trapezoids, and spheres that fight for attention in downtown Dallas. After purchasing the land, Bradley looked to the most famous triangle-shaped building, Manhattan’s historical Flatiron. Bayoud had his name: the Bayoud Flatiron. For the design he turned to Arquitectonica’s Bernardo Fort-Breschia. The building Fort-Breschia created was a rectangular mass intersected by a tapered vertical mass, both of which sat on a triangular base supported by a giant rock and a pillar. It looked a bit like The Flintstones meets 2001. “I saw the Flatiron as being a sculptural element to break the monotony and to really sort of give a focal point to the area,” Bradley says. It took several months to finish the plans, prepare the brochures, and complete the market studies. Then it was time to announce the project to the press.

The press that announced the project, however, soon denounced it. The decisive Flatiron piece appeared March 2, 1985, when David Dillon, architecture critic of the Dallas Morning News, wrote a commentary on the architecture-as-art rage, with Bayoud and his Flatiron as examples of the self-absorption of Dallas’ Young Turks. Titled “Where Is Dallas Architecture Going?”, the article said that the unbuilt Flatiron raised ominous questions for the future. “Beneath the brashness and hype lurk some alarming ideas about architecture: that buildings are pieces of flashy sculpture, that standing out is better than fitting in, and that blowing the competition away is the biggest high of all.”

A few weeks later Bradley was in the newspaper again. In a cover story for the “Unique” section of the Dallas Times Herald, he did some criticizing of his own. The story said: “Dallas is losing a golden opportunity to make history with its colossal building boom. Consider the Egyptians, who left behind the awesome pyramids. Or the power of Rome that lives on in the Coliseum. So what is Dallas leaving for generations yet unborn? ‘Boring, uninspired, ugly glass boxes,’ says Bayoud. ‘It’s downright pathetic.’ ”

“Unique” also quoted Bradley as saying that developer Trammell Crow had built a bunch of schlock, a breach that outraged the Dallas development community. In two months Bradley Bayoud had unwittingly established himself as the enfante terrible of Dallas development.

Today he groans at the memory. “When I read it, I went, ‘Gulp. My God.’ I wanted to call Crow and the others, but I thought that might make it worse. When I run into the Crows here and there, I feel really guilty because I think they may have misunderstood. What I was talking about was his early work and the warehouses. I kept saying that I thought his new stuff was the best in the city.

“Controversy works in two ways. In art, it’s great, because when you have controversy, people want to read more about you and find out what you’re about. In business it gets you a lot of attention. But in a lot of ways it’s a negative, and it does you more harm than good.”

At one time, the Bayoud Flatiron was 29 per cent preleased, but it’s doubtful that the building will ever go up. “I probably lost the chance to lease it quickly,” Bradley says. “After that article came out, nobody would touch it. People would say, ‘That’s the weird building we read about.’ So, yeah, criticism can hurt. If you get a pan of your work in the New York Times, forget about a gallery picking you up or anybody trying to buy your pieces. Critics have power. It’s never been part of development before, but it will be.”

The market in the Crescent area softened, and Bayoud put his land up for sale. Several projects were pending for Bayoud Interests. The firm was gathering enough land in North Dallas to create a new-style residential neighborhood, and Bradley was interviewing “Texas’ best architects” to fill the neighborhood with a collection of “New Texas residences.” He was also merging art and architecture by developing a group of buildings for a functional exhibition with the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. But for the moment, Bradley Bayoud is reducing his staff and shifting most of his energies from the construction crane to the paintbrush. “The market is down, and I’m dedicating myself to art,” he says.

Connections Are Everything

Twinkle and Bradley are lunching at Brook Hollow, Dallas’ most exclusive country club, whose shady oaks and Old South gentility seem out of place in a seedy neighborhood near downtown. Twinkle is immaculately costumed in a boldly striped emerald-green and black dress. Vivid green triangular earrings dangle from her earlobes, and her hair is pulled back tightly from her brow. The look is pure Alexis from Dynasty. Bradley is in a double-breasted suit—slate-gray, of course, his trademark color. Since I last saw them, Twinkle has made her acting debut. Her acting career began much like her real estate career: with a seated dinner party for twenty at Dallas’ Mansion on Turtle Creek—the sound of money dropping on the marble floor. For the occasion—a dinner in honor of her acting coach Stanley Zareff—Twinkle served salmon mousse and veal chops, punctuated by chile ancho sorbet, two good California wines, and numerous bottles of Louis Roederer Cristal Brut. Her debut had been less upscale than the dinner: an acting workshop for twenty at the Bathhouse Cultural Center at White Rock Lake, instructed by Zareff. Twinkle, however, handled herself like a star.

Her two scenes, one from Murder at the Howard Johnson’s and one from Beyond Therapy, required a costume change each, and for the curtain call she wore a showstopping Zandra Rhodes covered in tiny appliqued stars. Between scenes Twinkle and the other actors stated their lifetime goals via a prerecorded video shown on a bank of TV monitors onstage. Twinkle’s was simple: “To be discovered by Aaron Spelling. To be a major star, very powerful, and I’ll come to any charity event you want me to.” But her final appearance onstage was perhaps her most dramatic. After the rest of the cast had appeared, Twinkle emerged—the star—carrying a dozen red roses for instructor Zareff.

Connections are everything in the world in which Twinkle and Bradley revolve, and the Bayouds rarely miss an opportunity to connect. Consider the constellation: Stanley Zareff had been a drama instructor for Dynasty’s Catherine Oxenberg. Twinkle had met Oxenberg through English Tatler magazine’s Izzie Taylor. The Zareff acquaintance, coupled with Twinkle’s fierce determination, landed her a coveted spot in the three-week Dallas seminar, which is closely scrutinized by casting directors looking for new faces. After the showcase most of the others returned to their apartments, but Twinkle and Bradley hosted the dinner party for Zareff, a casting director, and a few other actors. The next week Twinkle flew to New York for another acting class.

Then Bradley and Twinkle were off to the Bahamas, where 75 private jets delivered guests for the wedding of Houston socialite Joanne Herring. From there they returned to New York, then they flew to Los Angeles, where they celebrated their eighth wedding anniversary, went to a number of parties and chic restaurants, and were seen with superagent Swifty Lazar, Dyan Cannon, Donna Mills, and George Hamilton. But the trip wasn’t all flash. In New York Bradley had rented a studio loft and hired an assistant to start stretching canvases for his official return to art last fall. Already the New York art world was buzzing. “I think Bradley will do very well in New York,” says Andy Warhol, “because Twinkle has such a funny name.”

And Twinkle? Out on the coast in late August a low-budget film titled Club Sandwich was shot. It’s the story of a couple’s desperate escape from Chicago to the bawdy beaches of a Club Med vacation. In one scene Twinkle, in a chic business suit, walks demurely in an office setting; in another she flits about in T-shirt and short shorts on the beach—an important young actress making a brief, nonetheless historic, film debut. She landed the part through the efforts of Roger and Julie Corman.

“She wants fast results,” Bradley says of his wife’s determination. “She finishes one acting class and wants Aaron Spelling to call her up. And he probably will.”

The food they are eating at the country club is light and fashionable—Cobb salads with iced tea—and so is the conversation. It quickly turns to a statement Bradley made in Texas Homes that he and Twinkle represent the New Texas.

“We are part of a new youth in Texas, that’s part of art and culture.”

Twinkle snickers. “That’s Bradley’s quote,” she says. “Don’t put me in it.”

“Well, it’s kind of a heavy thought,” says Bradley.

When the salads are finished, Twinkle puts on a pair of jet-black Hollywood shades as the waiter pours more iced tea. “She’s going to be on Dynasty,” Bradley predicts, “the new sex symbol.”

The Newest Dream

The epilogue is that everything has changed in the Bayoud household except the furniture. The furniture always stays the same, a stationary set for a changing play—until someone comes along and offers the right price. On a wintry afternoon Twinkle descends from the staircase and plays hostess over her silver tea service in the living room. She wears an unidentified lavender suit, with her hair long and swept back over her ears, giving her face a more severe and angular look than usual. She’s all eyes and smiles, but she nervously clenches her fists as her conversation revs into high gear. Bradley emerges from the kitchen in his usual suit, tie, and sunny disposition. The changes? The Bayouds have sold quite a bit recently, making way for the new. For Bradley, it was trading development for art. For Twinkle, it was giving up real estate for acting. She’s serious about it.

“Fulton Murray’s [of Murray Properties] right-hand man called and asked me to come to his office,” Twinkle reports. “We talked all the terms out and settled on the money in a week and a half. It’s kind of the American dream: to build something up and then have somebody come along and buy it out. When I called my sales troops together and told them the news, there were tears. Crying. They were all boo-hooing in unison. Mass hysteria. I didn’t realize I could have been a cult leader.” The mourning didn’t last long. The women moved on to new employers. Twinkle began working her three coasts. “It’s hard to live on three coasts,” she says. “Dallas is in the middle, and it’s so much easier to commute from here.”

To keep up with old and new friends Bayoud and Bayoud took out an ad in the December Interview to wish everyone happy holidays. Twinkle, missing the thrill of sales, has taken on fundraising for everything from the preservation of Galveston to the grand opening of the Crescent (she is selling $5000-per-couple tickets). Bradley has started taking acting lessons in New York and creating computer art on the Macintosh in his loft.

“I guess we’re a little more bohemian now,” Twinkle says. “A little more artistic, not so business-aggressive.”

“Bohemian!” says Bradley. “I don’t think that’s true. We’re in the mainstream. Bohemians aren’t in the mainstream.”

“Well, we’re still pretty crazy,” says Twinkle. “Maybe it’s being twenty-eight on the verge of thirty.”

For a moment they stop to consider their goals.

“Mine is to do significant work, to be appreciated by the public as an actor or a painter,” says Bradley.

Twinkle laughs. “Mine,” she says, “is not to become thirty.”

Mark Seal is a freelance writer who lives in Dallas.

Twinkle’s Tips

How to have that rich and famous life.

Try to develop your own style in dressing, business, and entertaining. When I went to work, I didn’t go out and buy Adolphos. I combined my youth and my professionalism.

Don’t be seen at the trendiest places. Make the places you go the places where everybody wants to be.

Let your subconscious work for you. Give it goals and problems to solve while you sleep. Your subconscious may be more brilliant than you are.

Make sure your secretary doesn’t gossip! Your correspondence with politicians, businessmen, or celebrities can’t fall into the wrong hands, i.e., an enemy or the National Enquirer. This is death to a friendship or a business relationship.

Treat the press with respect. If you are inaccurately quoted, slit your wrists—no, try to keep your cool and remember that reporters are merely human.

Charities use social interaction to raise money. Donate time as well as money.

When dealing with a married couple, never team up with the wife or the husband. Always treat them equally.

Remain poised and confident at all times. If you are negotiating, don’t be the one who slams the book shut and throws the coffee mug at the wall. If you do, you’re the loser.

When you’re young, you really don’t have to spend a lot of money on clothes and jewels. Your youth is your beauty. Save it for when you’re old and need that expensive wardrobe.

Mind your manners. Always return phone calls and correspondence.

Work as hard on friendships as you do at your profession. It’s lonely at the top.

Twinkle Bayoud

Bayoud Ink

The young kids get the hot press.

Twinkle Bayoud’s sparkle-plenty dress by Karl Lagerfeld was the talk of the evening with its unique design of the bugle-beaded guitar aglitter in black and white on her back (reminding one of the piano keyboard that artist Andre Miripolsky created for Elton John).

—George Christy, Hollywood Reporter, August 3, 1983

Twenty-seven-year-old realtor Twinkle Bayoud owns a company that deals in exclusive real estate. With Dallas in her pocket, she has synthesized a flair for publicity, a high-fashion sense, and poise derived from an early modeling career into a formula for success already making international waves.

—Australian Vogue, September 1983

Gorgeous Twinkle and her handsome husband, Bradley, flew in from Texas for the evening. Wearing a tulip-collar pink satin gown by Bernard Perris, Twinkle was dinner-partnered with Dudley Moore. . . . Shera Danese Falk sat on Dudley’s left, pulling at her strapless dress, but Shera’s ooh-la-la boobs did pop out at one point.

—George Christy, Hollywood Reporter, March 14, 1984

Andy Warhol and Fred Hughes were joined by Texas’ dynamo realtor Twinkle Bayoud and her master developer husband, Bradley Bayoud. All went on to Raymond Lee’s elegant Palette restaurant for a dinner of a dozen delights.

—George Christy, Hollywood Reporter, July 19, 1984

Catherine Oxenberg joined her tricoastal chums Twinkle and Bradley Bayoud of Texas and Interview‘s president, Fred Hughes (one of our best-dressed American gents), at their soirée in the Garden Room of the Bel-Air Hotel.

—George Christy, Hollywood Reporter, July 27, 1984

“How can they have all this and be just twenty-nine?” asked one delegate as she stuck a cracker into the caviar at the Bayouds’ party for the Delaware delegation to the Republican National Convention.

—Dallas Times Herald, August 10, 1984

In Manhattan, Twinkle was toasted by New York fashion matriarch Diana Vreeland with a dinner. Twinkle also took in a party in Los Angeles given by Bob Finkel, who produced the Olympic spectacle. Said his wife, Jane, “You should have married my husband. You’d be Twinkle Finkel.”

—Nancy Smith, Dallas Times Herald, August 17, 1984

Life is like a canvas on which I can paint anything I want.

—Twinkle Bayoud, as quoted in Park Cities News, June 13, 1985

More astonishing than the scenarios of Dallas, here is the true story of a rich little girl. . . . She eclipses Sue Ellen, Pam, Jenna, and the others. The new little queen has a crazy charm, dollars by the bundle, and insolent luck. As imaginative as the scriptwriters of the celebrated series are, they couldn’t have come up with a better name.

—Madame Figaro, July 1985

Shirlee Fonda arrived with Dallas’ tip-top realtor Twinkle Bayoud and her master developer husband, Bradley, who are celebrating their eighth wedding anniversary. “I’ve survived the seven-year itch,” winked Twinkle, who’s taking acting lessons.

—George Christy, Hollywood Reporter, August 22, 1985

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas