Here’s Robert Jeffress, talking to the hundreds of thousands of people watching conservative cable news on a typical Friday evening, and he’s defending President Donald Trump against the latest array of accusations in the news this week. And he isn’t simply defending Trump—he’s defending him with one carefully crafted Bible-wrapped barb after another, and with more passion, more preparation, more devotion than anyone else on television.

As Lou Dobbs finishes his opening remarks, Jeffress laughs and nods. It’s early January, about two weeks into what will prove to be the longest government shutdown in U.S. history. Across the country, hundreds of thousands of federal workers are missing paychecks, worrying about mortgages, car payments, utility bills. Some have started going to food banks. But Dobbs waves his hand up and down and tells Jeffress that he hasn’t heard anyone—“literally no one!”—say they miss the government. The jowly host revels in Trump’s threats that the shutdown could continue “for months, if not years,” if that’s what it takes to get more wall built on America’s border with Mexico.

Jeffress, speaking from a remote studio in downtown Dallas, agrees completely. “Well, he’s doing exactly the right thing in keeping this government shut down until he gets that wall,” he says.

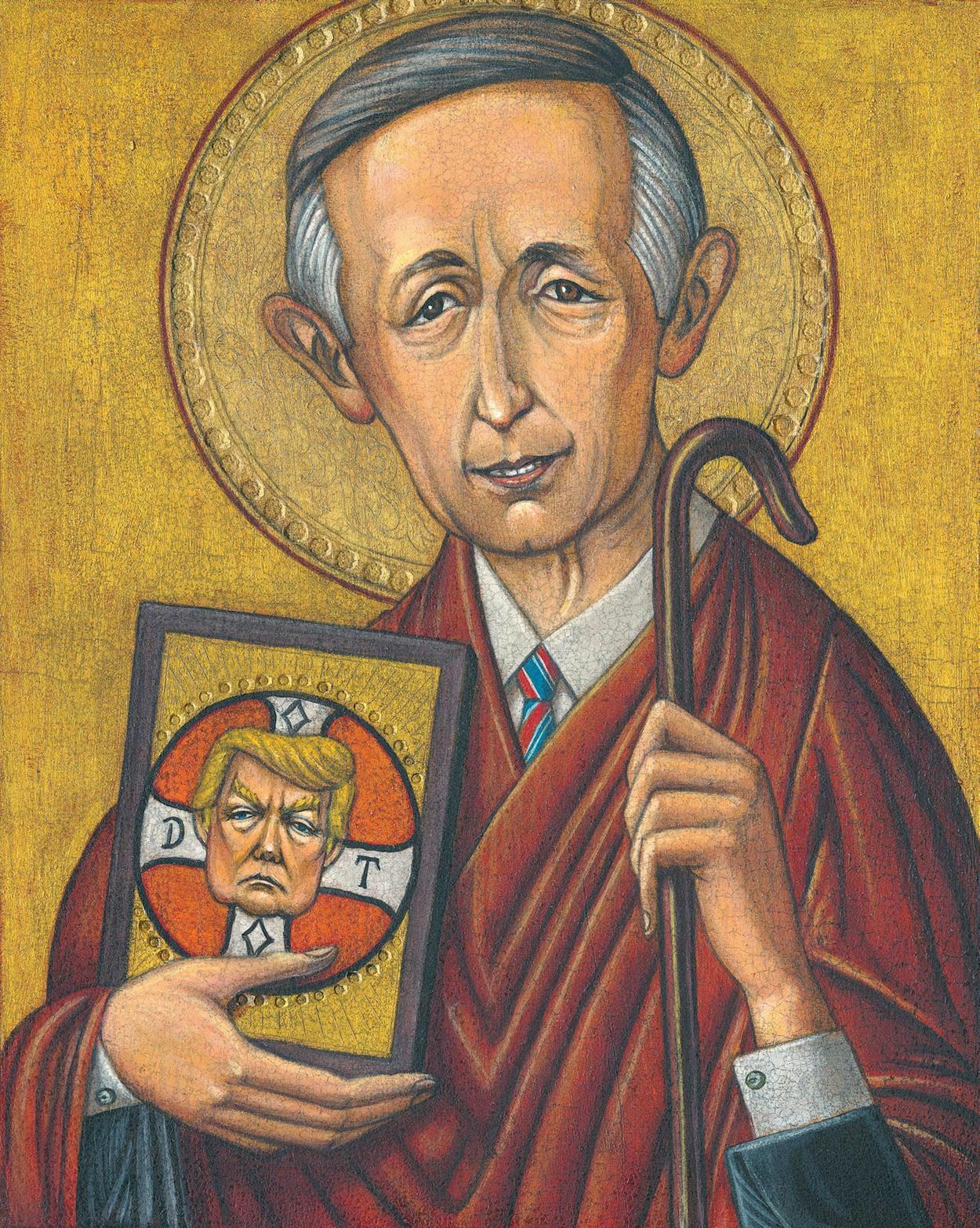

Jeffress is the senior pastor at First Baptist Dallas, a 13,000-member megachurch that’s one of the most influential in the country, but he’s known best for appearances like this one: he’s often on Fox & Friends or Hannity or any number of sound-bitey segments on Fox News or Fox Business. His own religious show airs six days a week on the Trinity Broadcasting Network. He has a daily radio program too, broadcast on more than nine hundred Christian stations across the country, though it’s TV he loves best. Dobbs invites Jeffress onto his show nearly every week.

Jeffress continues. He cites the Old Testament tale of Nehemiah, who was inspired by God to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem. “The Bible says even heaven itself is gonna have a wall around it,” Jeffress adds. “Not everyone is gonna be allowed in.”

It’s not clear whether Dobbs buys this theological reasoning, but he’s at least amused by it. “What would be the point of those pearly gates if there weren’t a wall, right?” the host says with a Cheshire grin.

The pastor keeps going. “What is immoral,” he says, “is for Democrats to continue to try to block this president from performing his God-given task of protecting this nation.”

The 63-year-old Jeffress is trim and winsome, with a natural smile and a syrupy demeanor. Tonight he’s wearing a charcoal suit and a gleaming magenta tie with matching pocket square. As he speaks, the screen behind him shows generic patriotic imagery. He has the syntax and enunciation of a champion debater and the certitude of someone who believes he gets his instructions directly from God.

He is known for leaning into controversy, whether it’s declaring that Mormonism is “a heresy from the pit of hell” (which resulted in an extended public beef with Mitt Romney) or preaching a sermon titled “Why Gay Is Not Okay” (which resulted in a protest outside his church) or having two hundred or so members of his choir and orchestra perform a rendition of a hymn called “Make America Great Again” at a concert in Washington, D.C. (which resulted in not one but two approving tweets from President Trump).

He is also known, of course, as one of the president’s most avid and outspoken advocates. While other evangelical leaders were slow to get behind Trump—James Dobson, for example, wondered about Trump’s religiosity—Jeffress campaigned with him before the 2016 primaries even started, before Ted Cruz and Jeb Bush and Marco Rubio flamed out. If some evangelicals who now back Trump fret that they’ve entered into a Faustian bargain, for Jeffress it’s a wholehearted embrace. It’s become one of the most fascinating symbiotic relationships in modern politics: the pastor gets a national platform for his message and a leader who appoints conservative judges who will in turn restrict access to abortion; the president gets the support of evangelical voters he needs to win reelection, along with an energetic and effective promoter who can explain or excuse all manner of polarizing behavior.

When the Access Hollywood tape leaked before the election and America heard Trump brag about grabbing women, Jeffress went on Fox News to say that the candidate’s words were “crude, offensive, and indefensible, but they’re not enough to make me vote for Hillary Clinton.”

After the president said there were “some very fine people on both sides” of the deadly clash between white nationalists and counterprotesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, Jeffress appeared on the Christian Broadcasting Network to say that Democrats were falsely painting Trump as a racist. “Racism comes in all shapes, all sizes, and, yes, all colors,” explained the pastor. “And if we’re going to denounce some racism, we ought to denounce all racism.”

When the adult-film actress Stormy Daniels announced that she’d had a sexual encounter with Trump and was paid to keep quiet before the election, Jeffress explained in a Fox News debate with Juan Williams that evangelicals “knew they weren’t voting for an altar boy.”

Jeffress defended Trump when the president referred to a kneeling NFL player as a “son of a bitch.” He justified the administration’s separating children from their parents at the border. When Trump questioned why America would accept immigrants from “shithole countries,” Jeffress responded this way: “Apart from the vocabulary attributed to him, President Trump is right on target in his sentiment.”

Ten days before tonight’s appearance with Dobbs, Jeffress was on a different Fox show, scoffing at a Christmas tweet from Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a New York Democrat, suggesting that Jesus was a refugee. “There’s nothing in the Biblical text to suggest that Mary, Joseph, and Jesus came to Egypt to flee Herod illegally,” Jeffress said, laughing and shaking his head. “And they certainly didn’t come in a caravan of five thousand, threatening Egyptian sovereignty.”

No doubt Jeffress knows that a lot of the people waiting at the border are there precisely because they want to enter legally, as asylum seekers, but that didn’t come up on air. These television exchanges, usually over in five minutes, don’t allow for such distinctions.

During this evening’s three-minute discussion with Dobbs, Jeffress sounds more like a fiery Old Testament prophet than a turn-the-other-cheek Christian: he decries Democrats for supporting sanctuary cities laws he believes led to the death of a police officer in California. He says Michigan representative Rashida Tlaib is “despicable” for using “gutter language to curse our president.” He declares, “The Democrats are the party of immorality.” He calls Romney a “self-righteous snake.”

His animated ranting earns a belly laugh from Dobbs. Finally, the host tells him, “Pastor, good to have you with us!”

With that, the camera’s off. After wiping away his TV makeup, Jeffress will walk out of the studio, drive to his home in North Dallas, and spend the rest of the evening watching TV with his wife, Amy. He may even watch a replay of tonight’s show.

TV reaches people, and reaching people is important to Jeffress. And to reach people, he knows, you must understand who they are and how they will hear you. You must be, as the Apostle Paul once put it, all things to all people.

Here’s Robert Jeffress as a boy in the sixties, well-mannered and bright, so infatuated with the power of television that he dreams of one day becoming—of all things—an executive producer on a TV show. He’s so dedicated to this dream, so enthralled by show business, that he wakes up early some days to play his accordion before school on a children’s morning show in Dallas called Mr. Peppermint.

His family lives in Richardson, but they spend plenty of time at First Baptist, downtown. It’s a turbulent time for Dallas, where the president has just been assassinated, and for the church, which is reckoning with desegregation. First Baptist has always been enmeshed in politics: George Truett, who became pastor in 1897, gave his most famous sermon, about the separation of church and state, on the steps of the U.S. Capitol, in Washington, D.C. His successor, W. A. Criswell, is not shy either: He has decried the Supreme Court decision to desegregate schools as “idiocy” and suggested that Catholics do not make good presidents. In 1968 Criswell reverses his position on desegregation and is soon thereafter voted in as president of the Southern Baptist Convention. The move puts North Texas at the center of a massive conservative movement.

His ninth-grade speech teacher tells him, “Jeffress, you’re going to be a preacher one day, and it scares the bejeebers out of me because you can sell anybody anything!”

Young Robert absorbs all this. His parents campaign for Barry Goldwater in 1964. When he is fourteen, Roe v. Wade goes to court, just a short walk from First Baptist; he’s seventeen when the Supreme Court legalizes access to abortion. In 1976 Criswell endorses Gerald Ford from the pulpit, but Jeffress casts his ballot—his first—for a Democrat, a born-again Christian from Georgia named Jimmy Carter.

Although Jeffress is just a boy, people around him are already taking notice of his power to influence others. His ninth grade speech teacher tells him, “Jeffress, you’re going to be a preacher one day, and it scares the bejeebers out of me because you can sell anybody anything!” Criswell becomes his mentor, and in fact, when he’s a freshman in high school, Jeffress hears God tell him to abandon his executive producer dreams.

For the first fifteen years of his career as a pastor, at a small church in Eastland and then a larger First Baptist in Wichita Falls, Jeffress doesn’t get political. He rarely mentions abortion or homosexuality. But he learns the power of controversy in 1998, when a member of his church shows him two children’s books from the local library: Heather Has Two Mommies and Daddy’s Roommate. Jeffress announces that he will not allow the books to be returned. The city council takes his side, the American Civil Liberties Union sues the city, and the story makes national headlines. Eventually a court decides the library can keep the titles in the children’s section, but by then Jeffress has received letters and donations from all over the country. Church attendance goes up, and soon comes an expensive new sanctuary.

Jeffress will remember these lessons when he is invited, in 2007, to return to First Baptist Dallas as senior pastor. In his first few years back, he gives sermons with attention-grabbing titles on the marquee and makes controversial statements about, in no particular order, Mormons, Muslims, Jews, Catholics, gays, lesbians, and Oprah Winfrey. Almost a decade later, he embraces one of the most controversial presidential candidates of all time, and in 2018 the church reports the highest giving levels in its 150-year history. Now, like Criswell and Billy Graham, who was himself a longtime member of First Baptist Dallas, Jeffress has the ear of the president.

Through all this, he retains his affinity for television. In 2018 his entire family is featured on a TLC reality show centered on his oldest daughter’s newborn triplets. At First Baptist, the main sanctuary gets outfitted with six or seven high-definition screens that can be made into a long LED scroll that ribbons across the back of the proscenium. Sunday services are broadcast live on the church website, an operation that includes seven cameras, a team of grips and technicians, and a control room that rivals studios at CNN and Fox. The church posts his cable news clips on YouTube. Jeffress says TV accounts for a small percentage of his work but that Fox News—where he becomes a paid contributor under contract—is a “gateway to bring people into our ministry.”

And television, it turns out, is how he connects to the president, a man with his own affinity for reality shows. In mid-2015, after seeing Jeffress compliment him on Fox News, Trump tweets out the clip and has someone from his office—Jeffress doesn’t remember who—reach out so he can thank the pastor for the kind words.

When Jeffress recounts the story, he lowers his voice an octave to repeat the way he’s heard Trump describe it: “ ‘You know, I was watching TV one night, and I’ll never forget, I saw Pastor Jeffress saying, ‘Trump’s a lousy Christian, but he’s a good leader. ’ ”

The pastor interrupts himself to clarify. “Of course, I didn’t quite say it that way,” he explains, lest anyone think he called the president lousy. “I said, ‘He’s not a perfect person, but he’s a tremendous leader.’ ”

Jeffress has also heard Trump tell it this way: “I was watching television with Melania, and I saw Pastor Jeffress, and I said, ‘Look at his mouth move! Look at how quickly that mouth moves. It’s like a machine gun! I would never want to see that used against me someday!’ ”

Trump’s campaign asks Jeffress to pray at a rally in Dallas that fall, and soon the two forge what they describe as a friendship. The candidate sends nice notes or has his assistant email, and in early 2016, Trump invites Jeffress to join him on the campaign trail. The pastor spends a weekend with Trump in Iowa, where, both men understand, evangelical support can make or break a Republican presidential run. Jeffress says things like “I don’t want some meek and mild leader or somebody who’s going to turn the other cheek. I’ve said I want the meanest, toughest SOB I can find to protect this nation.”

Then Jeffress is at Trump Tower on the day of the election. The mood is not optimistic. Jeffress tells Trump he hopes they’ll stay friends, no matter the outcome. Trump asks him if he thinks evangelical voters will show up for him. The pastor says he does. Later that night, Jeffress and his wife go to the Hilton to watch the results come in. For a while, it’s slow and quiet, and the couple debate leaving early.

But as the evening wears on, the feeling in the room starts to change.

“I will never forget when the spotlight was thrown on the balcony of the ballroom,” he recalls later, his voice slowing for dramatic effect. “The president and the first lady and their family entered to the soundtrack of the movie Air Force One. It was a chill-bumps moment.”

After a speech, Trump comes down from the stage to shake a few hands. Spotting Jeffress, he walks over and puts his arm around the pastor. The boy who used to play his accordion on Mr. Peppermint is now standing next to the future president. “Did you see it?” Trump says. “Largest evangelical turnout in history!”

“Yes, sir, I saw it,” Jeffress tells him. “I just wanted to be sure you saw it.”

Here’s Robert Jeffress in his office, a year or so into Trump’s first term, speaking to a reporter: me. We have a bit of history. In late 2011, around the time Jeffress was first upsetting conservatives by criticizing Republican presidential front-runner Mitt Romney, I wrote a profile of Jeffress for D Magazine. In the story, I explained that despite the fact that I disagreed with him on virtually every issue—at the time, he was supporting a presidential run by Texas governor Rick Perry—I found Jeffress charming and personable. Yes, he insists that the vast majority of humanity will spend eternity in a pit of fire. But he’s also self-deprecating and disarming. I was curious about his political advocacy and how he squares it with the teachings of Jesus.

After the story ran, we continued to have lunch every couple of months, usually in his office. It’s on the sixth floor of one of the church’s eight buildings, with towering shelves of scholarly journals, framed covers of his books (he has written more than twenty), and floor-to-ceiling windows that look out over the Nasher Sculpture Center. We ask each other about family and work. We discuss news and politics and whatever’s happening in the world that week.

He’s completely engaged, attentive. With or without the TV makeup, he’s the same man. Same rapid-fire delivery. Same polite, saccharine manner. Same unapologetic born-again Baptist view of the world. He says he genuinely wants me to dedicate myself to Jesus Christ, and he prays for me and my wife. His goal is to save as many souls as possible before the end times. He knows journalism is important to me, and he reminds me that some of the greatest writers in history were Christians. I joke that I know he’d love to brag that he helped shape some sort of present-day C. S. Lewis.

Jeffress often tells his flock that God sends us tests and trials. I want to ask Jeffress if he thinks there’s any chance Donald Trump is a test from God—and if maybe he’s failing.

I’m also forthright: about my curiosity, about my dismay at the many things he says and does that have the potential to hurt so many people. He knows what I’m talking about, and he laughs and nods. We discuss my writing something about him and his friendship with the president. He likes the idea. Then he jokes, “Now, don’t pull a Michael Cohen on me!”

So for months, I attend Sunday services, hang out at church events, spend hours talking politics with religious conservatives, and meet over and over with Jeffress himself. The unlikelihood of the Trump presidency has occasioned much ink and froth about the many purported reasons that white evangelicals supported him: economic and racial fears, Supreme Court picks, abortion, the fact that he wasn’t Hillary Clinton, and so on. It’s also provoked condemnation of Jeffress and his fellow Trump-supporting religious leaders for seemingly abandoning Christian principles in exchange for power—for becoming “court evangelicals,” as historian John Fea, the author of Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump, puts it. Fresh-faced 2020 presidential hopeful Pete Buttigieg, a gay military veteran and a Christian, likes to say that support for Trump is in tension with much of the New Testament, including, for example, the way Jesus condemns those who truckle to the strong while neglecting the poor. Closer to home, Eric Folkerth, the senior pastor at the much more liberal Woods United Methodist Church, in Grand Prairie, writes an open letter to Jeffress in May, calling him “a Pharisee of our time.”

And so I press Jeffress to explain the choices he makes, to explain the things he says in front of the cameras. Jeffress has told me he was drawn to Trump’s leadership and intellect. “He’s a very smart person,” he’s said. “You don’t become a billionaire and president of the United States by being an idiot.” But none of that quite explains why a pastor goes out of his way to publicly defend the president’s every indiscretion. He could easily vote according to his views on the Supreme Court or according to his conscience on abortion without also going on TV, over and over, in front of hundreds of thousands of viewers, to explain away things like Trump’s adultery and language that inflames foreign policy. He could be in favor of immigration reform, for example, and not feel compelled to rationalize the separation of families. He could believe that God has put someone in power and still hold that person to a high moral standard.

Jeffress often tells his flock that God sends us tests and trials. I want to ask Jeffress if he thinks there’s any chance Donald Trump is a test from God—and if maybe he’s failing.

Here’s Robert Jeffress on a Sunday morning, surrounded by lights and cameras and flat screens the size of school buses, taking the stage with the confident stride of a talk show host. He’s looking out on an audience of roughly 1,600, with thousands more watching and listening in, delivering a sermon that’s at turns funny and thoughtful and ripe with references to pop culture and historic events and scholarly interpretations of biblical passages. Jeffress is wearing a dark suit with faint pinstripes, a red tie that glimmers under the lights, and a nearly imperceptible wireless microphone over his right cheek, and he’s nailing the timing of every joke and pausing for laughs and modulating his voice in just the right way to create connection.

Today’s sermon is about “the antidote to worry,” and it unfolds like a forty-minute brimstone-scented TED talk. In the first few minutes alone, he mixes in quotes from obscure authors, anecdotes from World War II, and the etymology of the word “worry.” Sprinkled throughout are also copious references to supporting Scripture; there are more than ten, from the Old Testament and New, in the first twenty minutes. After each citation, he pauses to let his words linger. His reasoning is based on the fact that every word of the Bible is literally true.

Jeffress agrees with the popular comparison evangelicals draw between President Trump and Cyrus the Great, the ancient Persian king who, according to Jewish tradition, allowed the exiled Hebrews to return to Jerusalem. Cyrus is thought of as a secular agent of God’s divine plan, and this oft-cited parallel is useful to Trump’s most enthusiastic backers as a way of explaining their support: they can champion him, they say, because there is a difference between the earthly realm and the heavenly one, between government and church. In an interview with the Washington Post, Jerry Falwell Jr. put it this way: “In the heavenly kingdom, the responsibility is to treat others as you’d like to be treated. In the earthly kingdom, the responsibility is to choose leaders who will do what’s best for your country.”

But keeping your realms separate is not so clear-cut when you’re both a pundit and a pastor. Jeffress, unlike his peers, is the full-time shepherd of a flock. In the lustrous sanctuary of First Baptist—the church has multiple six-story garages and crowded escalators and feels a little like one of the theaters or music halls a few blocks away in the Arts District—Jeffress preaches two sermons nearly every Sunday. He attends luncheons and prayer meetings and Bible studies. He visits people in the hospital and performs weddings and funerals. He helped raise more than $135 million for a renovation that included a new children’s building, sky bridges, and a dancing, LED-loaded fountain. At special events, visitors are given not a Bible but a copy of one of his books. “He is so right,” one of his members, a black mother in her thirties, tells me. “It is time to stop being wimpy about Christianity. I wish more Christians had the heart for the Lord that he does.”

Jeffress studiously insists that his politics and his pastorate are separate. “We don’t check green cards or passports at First Baptist Dallas,” he’s fond of saying. When he’s at the podium in church, he seldom utters a word about the president. And while some of the older men in the pews are wearing American flag and Israeli flag pins on their suits—and there’s at least one bumper sticker in the parking garage for QAnon, a far-right conspiracy theory alleging a “deep state” plot against Trump—it’s not like members are debating legislative policy in the halls. It’s more that there’s a general celebration and commingling of patriotism and piety. I recently attended services on and off for five months and never heard Jeffress mention politics explicitly in a sermon. I heard him talk about how heaven is a real place and what people do there: enjoy the relief of a job well done, share fellowship with loved ones, get to better know their Lord.

Though First Baptist doesn’t keep records on its racial demographics, the congregation seems as diverse as that of any megachurch in North Texas. Affluent older white people dressed in stiff suits and flowery dresses with matching hats. Young couples, the men in jeans and tucked-in button-downs, the women in cotton dresses. A black family spanning four generations. Immigrants from Latin America and Africa and Eastern Europe and East Asia. At the other end of the building, in a separate sanctuary, hundreds more people—mostly younger—watch Jeffress on a live broadcast.

About twenty minutes into his sermon about worry, Jeffress says something that makes me perk up a bit. He’s hoisting an open Bible in his left hand when his tone changes for just a moment, and he stares into the camera, his right hand gesturing to the breast of his pinstriped suit. “I can tell you from personal experience: God’s discipline is never pleasant,” he says. “There are times in my life—don’t ask for details, I’m not gonna give ’em to you—but I can tell you, there are times that I have not been doing the right thing, and God put his heavy hand upon me. And I can tell you for sure, I never want to experience that again.”

He explains that we don’t have to experience God’s discipline if we live our lives the right way. He makes another emphatic gesture with his right hand, this time with his thumb out in a way that evokes Bill Clinton.

“Today,” he says, we can “start walking in a new direction.”

As he always does, Jeffress invites anyone who wants to be saved to come forward and dedicate their life to Jesus Christ. His voice is soft. Even in a crowd of some 1,600 people, for a split second it can feel as if he’s talking to you personally.

“It’s no coincidence that you’re hearing my voice today,” he says.

When he’s done this morning, there are at least a dozen people walking down the aisles, ready to be born again.

Here’s Robert Jeffress in his office again, on a weekday afternoon in early fall. He’s sitting flat-footed in a blue leather chair, wearing one of his usual dark suits and satiny ties, like he’s ready to appear on camera at a moment’s notice, should the need arise. I’m sitting at the end of a big leather couch, a few feet away, with my recorder between us.

We’re talking about the distinction he makes between what he considers spiritual and political. I want to know if it’s really tenable, if it’s really honest. On Twitter, he promotes his sermons and events at the church right next to his appearances on Fox News. When his choir performed “Make America Great Again” in D.C., it was a de facto Trump rally—and now the song is in the church hymn database. He doesn’t just invite Fox personalities like Sean Hannity and politicians like Ted Cruz and Greg Abbott into his sanctuary; the church often uses their appearances as bring-a-friend promotions.

Our conversations over the months often return to this topic, and he agrees it’s an important one.

“If someone asks me to talk on a subject,” he says, “I ask myself the first question: Does the Bible have a particular point of view on this?”

The Bible has a point of view on many things, he explains. Some things, like capital punishment or whether a country’s leader has a right to defend its borders, he thinks, are clear. Other issues, like marginal tax rates and public health-care policy, are less clear. And besides, when Hannity was there to promote a Christian movie, they didn’t say much about politics at all.

What about when you call Democrats the “party of immorality”? I ask. Isn’t that crossing the line into politics?

“I think, in a lot of ways, the Republican party is just as spiritually bankrupt as the Democratic party, but at least at this point in time they are championing some moral principles like the right to life and the right of religious liberty.”

It’s an interesting equivocation, and I’m reminded how, in our exchanges, he has emphatically insisted that he’s not a Republican or a Democrat. He has also told me his congregation has plenty of Democrats, though I haven’t met one. When I ask him if he’d ever invite a Democrat or someone from CNN to speak at his church, he laughs.

“You know, I would have to think about it,” he says. Then he adds, “But if we haven’t, it’s not because they are Democrats. It’s because of the point of view they would articulate on these basic core spiritual issues. I mean, try to find me a pro-life Democrat leader. You can’t find one.”

“Basic core spiritual issues” is usually his answer when I press him on why he goes out of his way, again and again, to defend Trump. He cares about religious liberty—which for him essentially boils down to whether churches and businesses should be required to provide birth control for employees and whether businesses can deny service to gay or trans people. And nearly every policy discussion eventually comes back to what he sees as the national battle that started in Dallas when he was a teenager. He believes Roe v. Wade, not the issue of sexual assault or of judicial temperament, was at the heart of the fight over the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. The Democrats were worried that Kavanaugh’s rulings would “somehow lessen the number of babies being murdered every year in the womb through abortion.”

Gun rights is one of the two main issues on which he disagrees with the Republican party. The other is health care. He has been a vocal critic of Obamacare, but Jeffress does tell me, “The GOP is on the wrong side of this.”

This is why Trump is the sort of warrior evangelicals have long craved, a warrior who will fight for their beliefs regardless of whether he holds those beliefs himself. This is why Jeffress doesn’t worry about Trump’s personal behavior. “When you’re in a war, you don’t worry about style,” he explains. “Nobody would have criticized General Patton because of his language. We’re in a war here between good and evil. And to me, the president’s tone, his demeanor, just aren’t issues I choose to get involved with.” (When I look this up later, I learn that some top commanders and many members of Congress did criticize—and discipline—General Patton for verbally abusing and slapping two soldiers. He was suspended from his command and made to apologize.)

I ask Jeffress why, since he believes all sin is equal, abortion is more important than every other issue. Criswell, his mentor, and other past religious leaders didn’t feel nearly as strongly about the topic. Criswell stated publicly that life begins at birth and didn’t change his stance until after the widespread use of ultrasound technology. “Criswell and other evangelicals were just ignorant of the science,” he says. “We didn’t have the ability to view a life inside the womb as we do today and understand that that’s a real, live human being.”

What about children at the border and the administration’s policy of separating families? Doesn’t he think we should protect babies at our borders too?

“Look,” he tells me, “if you have a woman who is convicted of a bank robbery and she has an infant child and she’s sent to prison, I mean, her baby is going to be ripped from her.”

But of course, we have gradations of crimes in this country, and crossing a border—even if it’s illegal—is a far different thing than robbing a bank. This policy was instituted as a deterrent. I remind him that many people, including some Baptists, believe it’s a callous way to treat children.

“If we don’t secure our borders, we’re enticing the needy people, the persecuted people, to make a dangerous journey to come to this country or try to enter illegally, and I think, in part, we are morally responsible for doing that,” he tells me. He compares it to laws that hold homeowners responsible when a child strays into an unfenced pool and drowns. “We’ve got to figure out a way to secure our borders and at the same time deal equitably and justly with people who want to enter this country for legitimate reasons.”

I bring up some other children: the survivors of mass shootings. After the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, in Parkland, Florida, when students organized marches across the country to protest U.S. gun laws, Jeffress told Fox News viewers that changing the laws would not help because laws couldn’t change the evil in someone’s heart—though maybe displaying the Ten Commandments in schools could. Talking with me, though, he admits that mass shootings weigh on him heavily. He points out that, in Genesis, the primary reason God floods the earth is violence. “God hates those who harm others,” he says. “I don’t believe that the Bible or even the Constitution gives a unilateral, unconditional, unrestrained right for guns. The government has a right and responsibility to control that.”

Gun rights, in fact, is one of the two main issues on which he disagrees with the Republican party. The other is health care. He has been a vocal critic of Obamacare, but Jeffress does tell me, “The GOP is on the wrong side of this.” He says, “There ought to be a safety net” and “Americans want coverage for preexisting conditions” and that “before we dismantle something, we ought to have something better ready in its place.”

I ask Jeffress if he’d be critical of, say, someone like Democratic senator Cory Booker, if the public learned he’d had an affair with a porn star.

“I have to be consistent,” he tells me. “And consistent would say that my objection to Cory Booker would not be his personal life but his public policies.”

Here’s Robert Jeffress in January 2016, sitting on Trump’s plane between campaign stops in Iowa, and the pastor and the presidential candidate are finishing their lunch of Wendy’s cheeseburgers when Jeffress says, “Mr. Trump, I believe you’re going to be the next president of the United States. And if that happens, it’s because God has a great purpose for you and for our nation.” Jeffress quotes from the book of Daniel, chapter two, and explains, “God is the one who establishes kings and removes kings.”

Trump looks at the pastor and says, “Do you really believe that?”

“Yes, sir, I do,” Jeffress says.

Trump asks, “Do you believe God ordained Obama to be president?”

“I do,” Jeffress tells Trump. “God has a purpose for every leader.”

This is certainly not the way Jeffress talked about Barack Obama when he was president. Jeffress wasn’t a fan. Shortly before Mitt Romney secured the Republican nomination in 2012, Jeffress said he’d “hold [his] nose” and vote for him instead of Obama, despite believing that Mormonism is a cult and Romney is going to hell. (He’s also said that Jews, Hindus, Muslims, and nonbelievers are destined for hell.) He criticized both Obamacare and National Security Agency surveillance as violations of Americans’ freedom. In 2014, citing Obama’s support for same-sex marriage, Jeffress declared that the president was “paving the way for the Antichrist.”

Jeffress very much believes that an Antichrist will rise to power one day—possibly soon—before Jesus returns to earth. This isn’t entirely surprising. After graduating from Baylor, he attended Dallas Theological Seminary, a hub of twentieth-century dispensational theology, where he was taught, and embraced, the idea that God reveals himself progressively through different dispensations, or ages, and that these would culminate in an epic showdown between Christ and a fearsome enemy. Key events of this apocalypse would occur in Israel, went the thinking, and it was common for dispensationalists to publicly identify people they thought might be the Antichrist. Henry Kissinger was a popular pick; so was Mikhail Gorbachev, whose prominent birthmark looked suspiciously, to some, like the mark of the beast. Eventually most religious figures stopped trying to identify the Antichrist and the exact date of Christ’s return, but they didn’t stop believing that the supernatural confrontation was imminent.

At one point, not long after Trump meets with Kim Jong-un and it feels like we might be closer to nuclear annihilation than we have been in half a century, I ask Jeffress, mostly as a joke, whether evangelicals support this president because they secretly think he’s hastening the end times and the return of Jesus.

Jeffress lets out a quick chirp of a laugh. Actually, he explains, a lot of evangelicals view Trump as a brief reprieve from a downward moral spiral: everything from the removal of Ten Commandments monuments to restrictions on prayer in schools to the ways our culture flaunts sex and corrupts minds. He’s under no illusion that the Democrats won’t return to power again one day. Trump, he says, is a way to push in the other direction, if only temporarily.

He anticipates my follow-up.

“Why would Christians want to put off the return of Christ?” he asks. “To give us more time to save people.”

The truth for him personally, though, is that he also just likes Trump. Jeffress insists that theirs isn’t just a quid-pro-quo sort of friendship, a calculated, cynical partnership. He says he genuinely enjoys Trump’s company. He’d like to think they’d be friends regardless of the presidency.

Jeffress says Trump isn’t as impulsive as he might seem. He says the president has told him how he workshops insulting nicknames he plans to call opponents on Twitter. He says he watched as Trump agonized at the White House over what to do about DACA recipients. He’s seen the president demonstrate diligence and control, unlike the raging character often depicted in the press.

Several times in our conversation, Jeffress plays it a little safer and parses his words, saying that he and the president “aren’t bosom buddies.” Is he protecting himself in case one day his association with Trump becomes toxic?

“Not at all,” he says. “I just want to be as accurate as possible.”

A few months after his inauguration, Trump boasts about issuing an executive order instructing the Department of the Treasury not to pursue religious organizations when they violate the Johnson Amendment, which prohibits nonprofits from making partisan political statements, a restriction Jeffress has spoken out against for more than a decade. Then, in May 2018, the Trump administration does something even more important for evangelicals: it officially relocates the American embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, much of which is regarded under international law as occupied territory.

Jeffress, the lifelong dispensationalist, is invited to give the opening prayer at the new embassy’s dedication. He’s there, in Jerusalem, standing at the lectern with his eyes closed. He’s just feet from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Ivanka Trump, and Jared Kushner—all Jewish, all going to hell in Jeffress’s view, all sitting together in the front row.

After thanking God for the blessing and protection of Israel, and for the work of both Netanyahu and the U.S. ambassador to Israel, Jeffress thanks God for the “tremendous leadership” of Donald Trump. “Without President Trump’s determination, resolve, and courage, we would not be here today,” Jeffress says. “We thank you every day that you have given us a president who boldly stands on the right side of history but, more importantly, stands on the right side of you, O God, when it comes to Israel.”

A few months after that, in August, the White House hosts an elaborate dinner for a hundred or so evangelical leaders from across the country. Franklin Graham is there. So are James Dobson and Paula White, a TV host and pastor of a Florida megachurch. Jeffress is one of the preachers Trump thanks by name.

Reading prepared remarks, the president lists his evangelical-friendly accomplishments: issuing orders limiting government funding for groups that provide abortions, helping to free an American pastor being held in Turkey, moving the embassy to Jerusalem. Of course, there’s no record of him mentioning any of these issues before campaigning for president and meeting people like Jeffress.

At the end of his short speech, Trump thanks the religious leaders. He calls them “special people.” Then he looks up from his script.

“The support you’ve given me has been incredible,” the president says. “But I really don’t feel guilty, because I have given you a lot back.”

Here’s Robert Jeffress at a Maggiano’s in North Dallas, standing in front of two hundred or so people at an event called Dinner With the Pastor. Every few months, prospective church members are invited to have a meal and conversation in a private room, all on First Baptist’s tab. The massive serving plates on each table are full of ravioli slathered in cream, balsamic-glazed chicken, and meaty lasagna. There are Frisbee-size crème brûlées and gallons of iced tea. The highlight of the evening, though, is when attendees are invited to ask the pastor anything they want.

One woman says she campaigned for Trump and wants to know if Jeffress really told him he knew he would be president. Jeffress recounts the conversation they had over Wendy’s cheeseburgers. But he adds that he doesn’t consider himself a Republican. First Baptist, he says, has “plenty of people who love President Trump and people who don’t love President Trump.”

To watch him find new ways to justify his support is as impressive as it is exasperating.

Someone wants to know when Jeffress finds time to read the Bible. Someone has a specific question about a verse in the book of Isaiah. Then a woman with an Australian accent asks Jeffress if Trump is saved. The room gets quiet.

Jeffress explains that early on in his relationship with Trump, he asked, “Mr. Trump, what do I say when people ask me about your faith?” He says Trump responded, “Tell people that my faith is very important to me but that it’s also very personal.”

Then someone asks if he agrees with the president about the news media. Jeffress looks right at me and smiles. He tells the audience that his mother was a high school journalism teacher. Her former students went on to work for some of the best newspapers in the country. “I honestly believe that most of the media tries their hardest to get it right,” he says, adding that the freedom of religion and freedom of the press are inextricably linked by the First Amendment.

Over the following weeks, Jeffress and I discuss Russia and the forthcoming Mueller report, the joys of raising children (he has two daughters), the #MeToo movement and the church’s relationship with women. Every time we talk—no matter the headlines, no matter the president’s latest inflammatory remarks—Jeffress is steadfast in his defense of Trump. When the Mueller report is released in April and shows ample evidence of obstruction of justice, Jeffress says he still believes the entire investigation has been a political ploy to damage the president.

To watch him find new ways to justify his support is as impressive as it is exasperating. I ask him if he’s bothered when the president tells easily disprovable lies—like when he claims, contrary to the evidence, that special prosecutor Robert Mueller is a Democrat.

“I operate under the assumption that the president knows more than we do,” he says. “I think he probably has insight into that investigation that I don’t have.”

Not once, in all the months we’ve met, has Jeffress criticized Trump. I want to know if he is at all concerned by the cost of this allegiance. I ask if he worries about turning off seekers with what they might perceive as his hypocrisy. Even Billy Graham ultimately regretted his involvement with Richard Nixon.

He tells me he isn’t concerned. He endorses the president’s policies and not necessarily his behavior, he says, and most people are smart enough to know the difference. I ask if he worries that Trump is driving deeper the wedges in our society or stoking dangerous ideologies and emboldening nefarious actors. He tells me he believes the president has merely exposed the division in our country and that a public figure isn’t responsible when someone misinterprets a message as a call for violence. “There have been screwballs and zealots throughout history who have taken the truth and twisted it,” he says.

I ask if he at least holds Trump accountable. Does he ever criticize the president in their private meetings? “If it had happened, I wouldn’t tell you about it,” he replies, “because I just feel like friends don’t do that to one another.”

I ask him whether Trump might be a test from God, a test of whether Jeffress’s devotion is to the Bible’s teachings and requirements or whether it’s to a powerful leader whose policies he finds agreeable.

“You have to operate on the best information that you have, and what we had in 2016 was the choice between two diametrically opposed candidates,” he says. “One was pro-life, pro–religious liberty, pro–conservative judiciary. His name was Donald Trump. One was a pro-choice candidate who would not stop an abortion or limit an abortion for any reason at all. It could not have been a more clear choice at that point.”

Did he consider any of the sixteen other Republican candidates, most of whom would have appointed pro-life judges?

“I don’t think any of them could have won,” Jeffress says.

Jeffress is often asked what it would take for evangelicals to walk away from the president. If the economy collapses, he tells me, people will probably want a change. And if the president were caught being unfaithful to his wife while in office, he could see people having a problem with that. But more than anything, it would take a change in policies.

“If he said, ‘You know, I think we’ve got enough conservatives on the Supreme Court. It’s time for us to have some more moderate views and balance things out.’ Or if he suddenly decided, ‘You know what, I used to be pro-choice, and then I turned pro-life. I’m gonna go back to pro-choice again.’ I mean, those would certainly be deal-breakers, I think.”

Then he clarifies. He knows his audience. What he meant was that these changes would be deal-breakers for evangelicals politically, not for his own relationship with Trump.

“I’m his friend,” he says. “I’ll never walk away.”

This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “The Pastor and the President.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads

- Donald Trump

- Dallas