A massive globular green head, outraged about something, scowling and bellowing. It’s puzzling to me why this is my first memory, since I would have been only a year old when The Wizard of Oz was re-released in 1949. It seems highly unlikely anybody would have taken me to see it at that age, and almost impossible that I would remember it if they had. But there it is anyway, lodged somewhere deep in my brain, a nearly precognitive visual jolt.

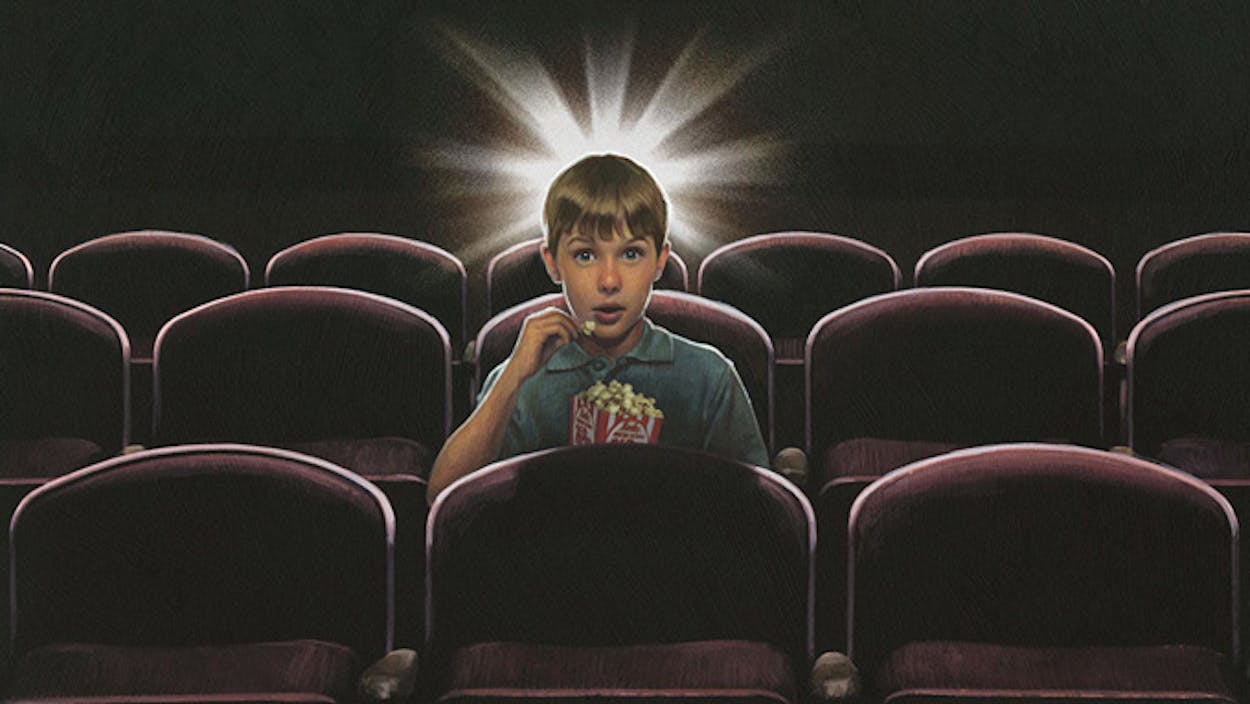

Whether my encounter with the Great and Powerful Oz really happened at such an early age or is some free-floating memory fragment from a later viewing of the movie, it still feels like the beginning of my life, a life that at times could be mistaken for an uninterrupted, unquestioning, non-curated private film festival. Since that first mysterious glimpse of an angry green head, I’ve liked going to movies better than almost anything. Even though the exurban multiplexes of today are strikingly different from the downtown picture palaces of my youth, they still carry the same anticipatory charge: the smell—no, the fragrance—of popcorn, the tribal nearness of others, the lights going down, the previews giving you a glimpse of what is to come in your future life.

In mid-century Texas, at least as I remember it, you didn’t go to the movies, you went to “the Show.” That singular noun was resonant. One week you might be watching Journey to the Center of the Earth, the next week Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, but you were always watching the Show. The movie would end, but the Show went on. It was a seamless pageant, constantly renewing itself with coming attractions that featured the words “Filmed in Glorious Technicolor!” or “Produced on Location Where It Actually Happened!” in letters that were rugged and massive, made to look as if they had been hewn from an ancient quarry. The theater might have been vast and ornate or it might have been a repurposed Quonset hut like the old Metro Theater on Butternut Street in Abilene, in whose perpetual darkness I spent so many of my boyhood hours and which sometimes during Saturday matinees would be suddenly full of frantic mothers in search of their children as the tornado warning sirens wailed outside.

There must have been ads in the newspapers with starting times for the features, but I’m not the first baby boomer to register memories of an era when movies weren’t watched from beginning to end. When you walked into the theater, Victor Mature was already fighting the gladiators in the arena. The Incredible Shrinking Man was already living in a dollhouse. You watched the movie until it was over, watched the previews and cartoons and then a whole other movie if it was a double feature, and then finally saw the first half of the movie, which explained why the Incredible Shrinking Man was shrinking in the first place.

The out-of-sequence storytelling never troubled me, probably because I didn’t understand what I was seeing anyway. I watched these movies unfold through a perfectly satisfying fog of incomprehension that, as I grew older, gradually lifted without my noticing. Until then, the logic that propelled the story and motivated the characters was invisible and unnecessary to me. Movies were moments: the steam hilariously erupting out of Bob Hope’s ears in Alias Jesse James, Alec Guinness falling on the detonator in The Bridge on the River Kwai, Tony Curtis getting his hand cut off in The Vikings. Nowadays, when I can’t stop myself from examining the structural flaws of every movie I see, annoying my friends with my merciless forensics, it’s hard for me to remember that there was a time when I just didn’t care, when I accepted everything I saw without expecting to understand it.

In Abilene and Corpus Christi, where I grew up, there was a sense of living on the outermost planet in the cultural solar system. I read about museums, concerts, art exhibitions, and Broadway plays in magazines like Time and Saturday Review, but they were abstract phenomenas, solar flares on a distant sun. Movies were real. You could actually see them, though they arrived with agonizing tardiness. It might be a full year or more after I had read about them that they would finally make their way to the Texas provinces, the prints already scratched from their multiple showings in bigger cities along the way.

Once every year or two, however, a movie would roll into town with its glamour uncompromised. These special events would be advertised as “the original roadshow attraction.” Roadshow movies had to be seen from beginning to end. They were too classy for anyone to be allowed into the theater after the feature had started. Gloriously bloated epics, they lasted as long as four hours, often starred Charlton Heston, and featured that ultimate signifier of high art, an intermission. The Ten Commandments, Lawrence of Arabia, Ben-Hur, El Cid, The Fall of the Roman Empire, How the West Was Won: these movies stamped into my consciousness an impression, lasting to this day, that length equals quality. They erased the possibility that I would ever evolve from a moviegoer into a cineast. Years later, in college, dutifully watching Italian neorealist cinema in sterile classrooms with no popcorn, I might nod my head in agreement with everyone else that The Bicycle Thief was the greatest movie ever made, but I would be privately thinking it was no 55 Days at Peking.

During my childhood, on the day a movie left town, it was gone from your life, most likely forever. When my children were young, I was fascinated by the way they would watch VHS copies of their favorite movies over and over, each viewing of Adventures in Babysitting etching it deeper into their memory slates. But when I was their age, movies were as ephemeral as shooting stars. They were made of light, and it followed without discussion that that light had to disappear. Old films were shown erratically on TV, but you couldn’t count on seeing any particular movie ever again. There was no way I knew of to possess them, unless you were a studio executive with a screening room and a film library. The epoch before the arrival of video recording had something in common with the centuries between the invention of the camera obscura and the discovery of photography, that tantalizing time when an image could be captured but not fixed, when it lived only in the direct sight or the recollection of the observer.

Maybe that helps to account for the urgency I still feel at the prospect of seeing a new movie in a theater, of catching that fleeting light. I’ve long recognized that I’m a shockingly undiscriminating moviegoer and have sort of a problem (low point, circa 1997: “One for 8 Heads in a Duffel Bag, please”), but the idea that watching a movie could be anything less than a special occasion, a potential life-changing event, never quite sank in.

Caught in the grip of that illusion, I went into the movie business myself. I’ve worked as a screenwriter for almost three decades, but I regard whatever success I’ve had in that field with a slightly crestfallen air, since all my produced work has appeared on television and not in the hallowed darkness of a movie theater.

One of the benefits of being a member of the Writers Guild of America, the screenwriters’ union, is the cascade of DVDs that arrives toward the end of the year so that we can vote for our favorite screenplays in the annual WGA awards. It’s an extravagant convenience, a great perk, but every year I find myself sorting through these DVDs with ambivalence, even a twinge of sadness. Watching these movies on my own TV means I won’t be watching them in a theater. For me, seeing a movie at home has a gnawing incompleteness about it, the feel of an empty ritual.

Only about four in ten Americans now go out to the movies regularly, but the falloff in theater attendance is not as large as you might expect it to be in an age of economic distress, digital streaming, and vigorous competition from television during its new golden age. The culture of moviegoing may be dying, but if so, it’s dying a nobly slow death. Something in the American identity resists its extinction.

I was fifteen and living in Corpus Christi when President Kennedy was assassinated. Lyndon Johnson proclaimed the day of Kennedy’s funeral, November 25, to be a national day of mourning, urging his fellow citizens “to assemble on that day in their respective places of divine worship, there to bow down in submission to the will of Almighty God.” On that day I went to a movie. I think I knew at the time that it was a shameful thing to do, but I was frightened and stir-crazy and feeling entrapped by the strangeness and hollowness that had suddenly descended upon the world. I wanted to go to the Show. There was nothing playing that I hadn’t seen except for The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm, which I would have had no interest in seeing had it not been made in Cinerama, an immersive technology like today’s IMAX in which a huge curved screen was filled with an image created by three side-by-side projectors.

The streets of downtown Corpus were empty. The theater was empty too, except for me and the friend I had talked into going with me and a scattering of other misplaced souls who had also chosen for whatever reasons to spend America’s national day of mourning watching The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm. The theater was not outfitted with Cinerama equipment, so the overlarge image on the screen was queasily distorted. The movie itself was antic and creepy, the colors muted (a bad print maybe), the actors’ voices sounding faintly dubbed. In the mood I was in, it was indistinguishable from a nightmare. I fidgeted in my seat, desperate for it to be over, ashamed of myself for watching it. Of all the places I could have been on that day, this nearly empty movie theater was the unseemliest, the ungodliest. But it was a place that was in its own way as familiar and comforting as home, the place where my shell-shocked mind had urged me to go.