This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

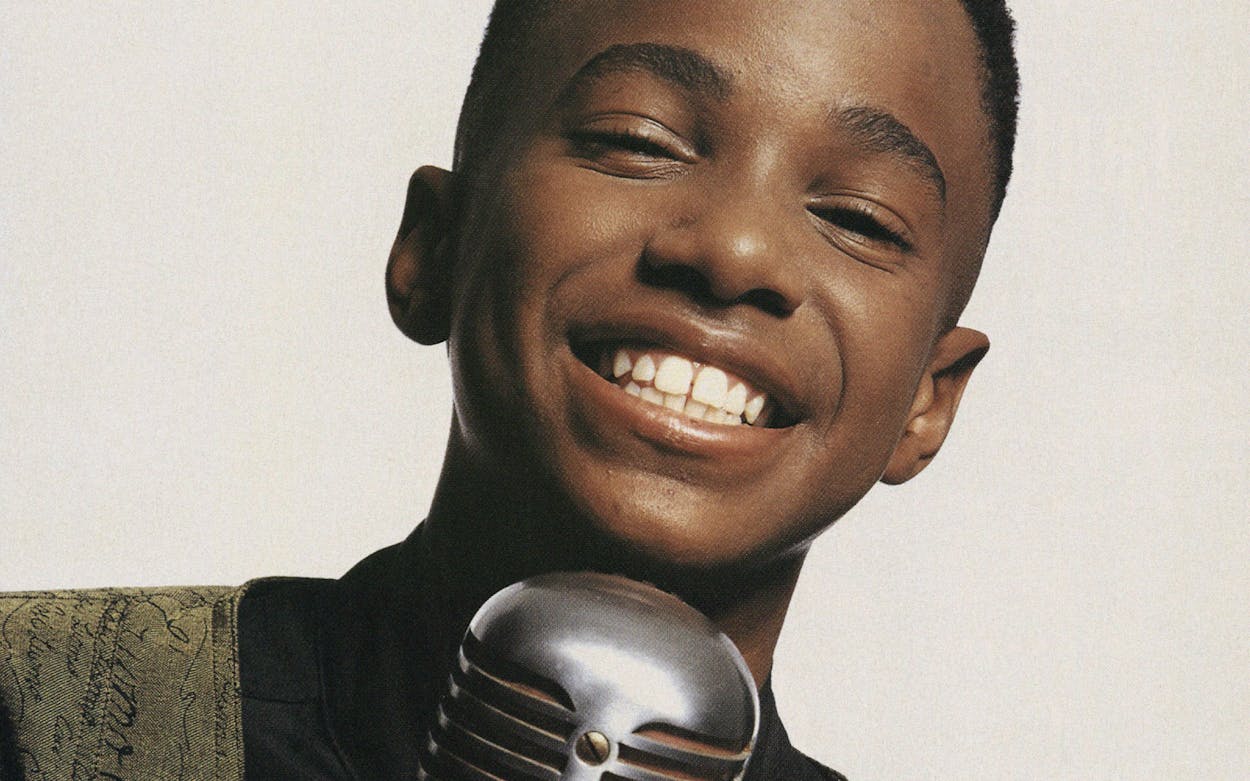

The first thing you notice about Tevin Campbell is the smile. One flash of his pearly whites and it becomes obvious: The kid’s got It. This is not some forced clenched-teeth expression you typically see affixed to the face of a superstar, but an engaging grin that breaks out spontaneously and frequently. Coming from a thirteen-year-old kid whose first record shot straight to the top of the charts, such unaffected behavior is nothing short of amazing. Then again, Tevin Campbell is not your run-of-the-mill teenage singing sensation.

Perhaps his refreshing attitude has something to do with the speed with which he achieved stardom. It came so quickly that his mother, Rhonda Byrd, hasn’t yet tired of the constant ringing of the telephone in their modestly furnished apartment in the South Dallas suburb of Lancaster. An annoyance to most people, the phone calls just confirm what she knew all along: She has three talented children.

“I always felt like one of them would get it,” Byrd says proudly from one end of the living-room sofa, while the object of her affection sits at the opposite end, keeping one eye peeled for the music videos on television. Tevin, the middle sibling (brother Damorio is eleven, and sister Marché is eighteen), first showed his potential while singing along to the radio at the age of three. He was encouraged to sing at weddings, at church, and at family gatherings. Then, two years ago, producer and musician Bobbi Humphrey received a tape of Tevin from one of her relatives, who was a friend of Tevin’s mother. Humphrey was sufficiently impressed by Tevin’s exuberant adolescent soprano that she organized a showcase in a New York City nightclub, made a home video of the event, and distributed it to music-industry talent scouts.

Tevin’s sweet vocals and cool composure under the bright lights persuaded Warner Brothers to sign him to a record contract. That coincided neatly with his successful audition for a role on Wally and the Valentines, a children’s television program that Lorimar Productions had in the works. In a matter of weeks, Tevin was on the fast track to the big time.

Tevin says he realized he was on his way when he got to meet his hero Michael Jackson—to whom he has been frequently compared—backstage at the 1989 Soul Train Music Awards. After some small talk, Tevin did what he does best—he sang for Jackson. “I was real nervous because he was a big star,” Tevin remembers. “He said I sang good and invited me to his office. I sang again, and he taped me. Then he asked me to come out to his ranch. It had a lake out front, a beach, a castle on a hill, a movie theater, a zoo, and a roomful of video games.” But rather than being dazzled by the fantasy of Michael Jackson’s world, Tevin instead took to heart Jackson’s sage advice. “He told me to be levelheaded and to take lessons to control my voice,” says Tevin.

The same night that he met Jackson, Tevin was also introduced to Quincy Jones, the producer, arranger, and performer credited with launching Jackson’s solo career. Jones, who was in the midst of making Back on the Block, his first album in ten years, had already heard a lot about Tevin from his protégé, Siedah Garrett, another promising newcomer who also had a role on Wally and the Valentines. Tevin, Jones thought, would be perfect to sing the lead on “Tomorrow (A Better You, a Better Me),” an uplifting anthem that resembles another Jones hit, “We Are the World.” When the time came to record, Tevin, ever the trouper, says, “I just walked in and did the best I could.”

Tevin’s best was pretty good. Jones’s album has been on the Top 200 album charts for almost a year. Tevin’s single was released last spring and reached number one on the black singles charts. He hasn’t had time to look back.

Since the start of summer, the pace has quickened. Tevin finished filming in the new Prince movie, Graffiti Bridge, in which he raps in “Round and Round.” (“I play myself, a kid named Tevin. Mavis Staples plays my mother. She’s staying out all night, and I’m staying out all night, following her around and being nosy. It was easy because that’s how I am.”) He also performed at a Dionne Warwick benefit for AIDS in Hollywood and was a guest twice on the Arsenio Hall Show and once on Saturday Night Live. He had a few weeks off, which allowed him to see his pals in Lancaster again, play Nintendo games, and read anything with Marilyn Monroe’s image or name attached to it. Then it was on to Los Angeles in August, where he took voice, dancing, and acting lessons from the best teachers in the business. Somewhere in the midst of all that madness, he managed to finish seventh grade at Lancaster Junior High School, earning A’s and B’s. Soon he will begin preproduction on his own album, and Quincy Jones will be the producer.

Surprisingly, Tevin feels that show business hasn’t changed his life that much. The biggest difference, he says, is that “before the record came out, I wouldn’t feel so confident about performing. Now I’m much more confident.” Friends are always asking what stars like Prince, Stevie Wonder, and George Clinton are really like. His standard reply: “They’re human beings. They all tell me to stay away from drugs and dangerous people.” Otherwise, friends treat him the same, which would be just fine with Tevin, if only he had more time. “I don’t get to hang out as much, because there’s too much happening with my career. I go out of town a lot.” At least until his voice changes, he’s going to be out of town a whole lot more.

- More About:

- Music

- TM Classics

- Dallas