Besides the Black Box that the starched and creased young military man carried, there were always two other items aboard President Lyndon Johnson’s Air Force One: Superior Dairies ice cream from Austin and Lady Bird’s Pedernales River Chili. Of the three, no one on the President’s staff doubted which was most important. If the fateful call came reporting that the sky above the Aleutian islands was darkened with ICBMs heading east, a man eating Hill Country chili might feel a slight advantage as he pulled the trigger.

Johnson took his chili every bit as seriously as the Box. Aside from Bobby Kennedy, nothing rated higher on the President’s Wrath Scale than greasy chili. Woe to White House Chef Henry Haller if he had not previously frozen Lady Bird’s chili and scraped the congealed grease from the top before placing the priceless stuff in the big jet’s compartments.

Like any sensible Texas president, Lyndon liked his chili without beans, accompanied with a glass of milk and saltine crackers. He had to have his bowl of red and glass of white at least thrice weekly.

Recently Haller, still White House chef, reported that the Jimmy Carters enjoy “simple American-Mexican food, such as tacos and enchiladas.” In the White House mess where senior staff officers eat, Thursday is Mexican food day. A recent menu included refried beans with Monterey Jack, chiles rellenos, and meat enchiladas, all prepared earlier and run through the microwave. Only the tacos with guacamole escaped the vibrations. Two-Alarm Chili, a celebrated legacy left by the late Texas Chili Mufti Wick Fowler, is also available. Mess maître d’ Ron Jackson reports, however, that Fowler’s creation is served without the enclosed red pepper, reducing the 2-Alarm to False Alarm. When Mexican food, however translated and microwaved, has permeated the bureaucracy, you may be sure it is loose in the land.

What hath Texas wrought? From the White House to probably your house, Mexican food, Texas style, Arizona style, New Mexico style, California style, sometimes even Mexican style, is being swallowed in record-number gulps. Of the nation’s eating and drinking places, which totaled $52.3 billion in sales last year, Mexican restaurants are the fastest-growing segment, up 10 per cent from 1975. Unfortunately most of them cater to the peculiar American eating habit of bolt and run, and their goods bear about as much similarity to properly prepared Mexican food as a capon does to a rooster. But if Texas is responsible for spawning these witless, trendy, dyspeptic eateries, it also contains within its borders restaurants serving entrees that celebrate the true flavors, sights, smells, and taste of the world’s zingiest cuisine. From the Yucatecan huevos a la motuleña at Houston’s Merida to the joyous New Mexi- can-style stacked enchiladas with chiles verdes at Tony’s Cafe in El Paso, Mexican food flourishes in Texas.

In discussing Mexican food in Texas, it will not astound anyone to learn that we shall be talking about two types, although to many people it doesn’t matter if their tacos originated in Guadalajara or Garland. The first is Northern Mexican, or Norteño-style Mexican food, which is eaten mainly by those the Census Bureau refers to as the Spanish-surname population: filetes, chicharrones, guisos, machacado, cabrito, chiles anchos (rather than jalapeños), agujas asadas, frijoles a la charra, alambres, to name a few (see “Words of Wisdom” for definitions). The second, which derives from Norteño-style cuisine, is Texas-Mexican food, naturally abbreviated Tex-Mex: tacos, tamales, chili con carne, nachos, rice, beans, guacamole, tostadas, chili con queso, enchiladas, etc.

In Texas, both Norteño-style Mexican food and Tex-Mex are predominantly influenced by the state’s 889-mile border with the four Northern Mexico states: Tamaulipas, Nuevo León, Coahuila, and Chihuahua. The astonishing variety of Mexico’s cuisine is explained not by the cohesiveness of ethnic groups, as it is in the United States, but by geography. The country’s great mountain ranges, intervening valleys, and climates ranging from Yucatan’s sultry tropical coast to the cool highlands around Mexico City to the semiarid deserts of Chihuahua have insured each region its individual cuisine.

This same geographical happenstance accounts for the startling number of foods that Spaniards, returning to Europe from Mexico in the sixteenth century, introduced to the Old World: corn, tomatoes, chocolate, peanuts, pumpkins, squashes, chile peppers, pineapples, avocados, turkeys, and tobacco. (The Spaniards in turn introduced to Mexico cattle, sheep, goats, wheat, and pigs.)

The many intricate dishes to be eaten in Mexico, and in a few restaurants in Texas, are based on a food system that began developing at least 8,000 years ago. The foundation of this complex cuisine is built on three things: corn, the bean, and 92 varieties of chiles.

First: Norteño

Northern Mexico, like South Texas, is semiarid cattle- and goat-raising country. But wheat and cheese are also chief products in the states of Sonora and Chihuahua, respectively. Norteño-style Mexican cuisine, which thrives in Monterrey, was born on the vast ranchos of the area. Visitors to Mexico will find that Monterrey is headquarters for cabrito, cabrito fritada (a stew that is thickened with kid’s blood), machacado, flour tortillas (rarely found south of San Luis Potosi), frijoles a la charra, agujas, and filetes.

Even Norteño tamales are different—smaller, thicker, resembling plump Vienna sausages. Laurence Miller, director of Laguna Gloria Art Museum in Austin, grew up on a large ranch south of Falfurrias and remembers such tamales, usually filled with pork, but often with javelina meat that had been cured in vinegar and salt. (They did not taste like Vienna sausages.)

Miller cheerfully shouldered the responsibility as family trencherman by clearing the table of carne guisada, calabacitas con crema (with cream), any number of caldos, usually de pollo or de res. There were also the omnipresent flour tortillas and the sidecars of frijoles a la charra or refried beans spiced with the pungent Mexican herb, epazote, and hot chile peppers. Miller remembers tacos, enchiladas, guacamole, and corn tortillas only from the family’s Friday-night outings to the Tex-Mex restaurant in Falfurrias.

From Trans-Pecos Texas comes an account of earlier Norteño-style eating habits. Since 1969, Marfa High School history students, under the wise tutelage of Mrs. Lee Bennett, have interviewed longtime residents of Presidio County, amassing recipes and cooking practices that date back to the 1870s. What emerges is the record of a diet based on pork, goat, game, flour, beans, chiles, and a few vegetables (such as the squash served on Laurence Miller’s table many years later).

The very poorest families, reported old-timer Adolfo Gonzales, lived on beans and flour tortillas for weeks until a goat was stolen or bartered in exchange for labor. Once obtained, none was wasted. The main dish was sangrita de chivo, a pioneer ancestor to the Norteño-style cabrito fritada, which is still served on Saturdays at Roger Flores’ Little Mitla Restaurant in San Antonio. Roger uses only the kid’s liver, heart, kidneys, and blood; the thriftier Gonzales used all that, plus the lungs, intestines, and fat. The head was also cooked for soup and the hide cured for winter blankets.

Bison, beef, or deer caldillo was a standard dish, because the dried jerky, which was a chief ingredient, would keep for days in saddlebags. Mrs. Lunitas, who moved to Marfa in 1913, gives another reason: “Indians would steal the cattle, horses, buffalo, and all the garden products. We saved the jerky by taking it with us.”

Hog-killing time came in late fall, and the pork, mixed with cornmeal, meant hogshead pudding for breakfast and hogshead cheese anytime. The Lenten season brought special bread puddings: the elaborate capirotada, made from toast, cheese, raisins, pecans, and brown sugar (nowadays made with French bread at Mario’s, Little Mitla, and El Mirador in San Antonio) and the simpler migas, made of stale bread, cinnamon, sugar, cheese, and raisins (and not to be confused with the scrambled-egg dish called migas served expertly at Cisco’s Bakery and Casita Jorge’s in Austin).

Words of Wisdom

A lexicon of Mexican food terms for those who already know their tacos from their enchiladas.

adobado: sour paste made with herbs, chiles, vinegar; thin strips of meat are marinated in the paste, then charcoaled.

agujas: ribs

ajo: garlic; according to Mexican folklore, it will cure any ailment of the digestive tract. alambre: shish kebab, often of beef and lamb; originally Spanish via the Moors

a la charra, a la ranchera: food prepared “cowboy” or ranch style; frijoles a la charra are whole pinto beans cooked and served like soup.

al carbón: charcoal-grilled

al horno: cooked in the oven

al pastor: cooked on a spit over a fire

antojito: appetizers; literally “little whim”

arroz: rice

asado: roasted or broiled

asadero: type of cheese with a distinct rubbery quality made typically in the states of Chihuahua and Michoacán

barbacoa: pit-barbecued meat

bolillo: Mexican hard roll; good ones taste like French bread

buñuelo: round wafer-thin crisp pastry

cabrito: kid, usually cooked al pastor

calabacita: Mexican zucchini squash

caldillo: thick, stewlike soup, usually with meat, potatoes, chiles.

caldo: broth or stock; also a clear soup

canela: cinnamon; whole sticks used to flavor everything from sauces to coffee

cena: supper

cilantro: leafy green herb with a strong, fresh taste, which goes well with onion and tomato, therefore used in most salsas crudas; also known as coriander or Chinese parsley

cochinito: suckling pig

comida: food; specifically, the main meal of the day, which in Mexico is lunch

comino: cumin; ground cumin seeds are used in various sauces; cumin powder is a dominant flavor in Tex-Mex sauces

chicharrón: crisp-fried pork skin (like crackling)

chilaquiles: any dish that makes use of old, refried tortillas; used often with eggs or chicken

chorizo: spicy pork sausage, usually seasoned with garlic, sweet red pepper, and hot paprika

chuletas: pork chops

desayuno: breakfast

empanada: a pastry turnover; in Mexico usually a dessert

epazote: strong, almost bitter herb used in cooking beans and other dishes

fajitas: grilled skirt steak

filete: steak filet

flan: dessert of baked caramel custard

flauta: long, tightly rolled fried enchilada; literally “flute.”

frijoles borrachos: ranch-style beans with beer added during cooking; popular around Monterrey, brewing capital of Mexico; literally “drunken beans.”

gordita: fat little corn cake

guiso, guisado: stew, stewed meat

helote: ear of fresh corn, sold from steam wagons on streets of most Mexican towns; served on a stick with lime, salt, and chile paste

hongos: mushrooms (also champiñones)

huachinango: red snapper, often prepared a la veracruzana (Veracruz style) with a chile, onions, tomato sauce

limón: lime

machacado: eggs scrambled with shredded dried meat

maíz: corn

masa: corn dough

manteca: lard

menudo: soup made from tripe, touted as a hangover cure

migas: eggs scrambled with chorizo

milanesa: breaded or floured, pounded, egg-battered, panfried meat

molcajete: mortar made of volcanic stone used to grind chiles and other ingredients for sauces

mole: dark, rich, chile-based sauce; apparently of Mayan origin, it may be Mexico’s oldest surviving, evolving recipe; made of many ingredients in varying combinations: chiles, ground nuts and seeds, garlic, chocolate, cinnamon, pepper, vinegar, various spices

nopalitos: cut, spiced, and cooked cactus pads, eaten as a separate vegetable or used in salad and egg dishes

olla: round earthenware pot

pan dulce: lightly sweetened bread, often flavored with anise

papa: potato

pepitas: pumpkin seeds; dried and salted, they are eaten as snacks

pescado: fish

picadillo: shredded beef and other ingredients, usually used as stuffing

picante: spicy hot (not temperature hot)

pico de gallo: a sauce or side dish hotter than a picante sauce, varying according to region or whim of the cook; literally “rooster’s peck”

piloncillo: unrefined sugar, usually shaped in a hard cone

pipián: sauce containing ground nuts or seeds and spices

pollo: chicken

pozole: thick soup of corn and meat

puerco: pork

quesadilla: tortilla turnover, toasted or fried, filled with cheese, sometimes with various other things from meat to beans to squash flowers

res: beef

salsa: sauce

salsa cruda: uncooked sauce made with fresh ingredients

sopa: soup

tomate verde or tomatillo: Mexican green tomato

torta: split bolillo with various fillings; sandwich

Hot Enough For You?

Chiles rank high on any roster of Mexico’s gifts to the world. Rich in vitamins A and C, they lend color and spice to hundreds of dishes and sauces. The thermal content ranges from the mild poblano to the hottest of all, Yucatan’s tiny chile habanero, whose bite feels like the sting of hundreds of giant army ants. Nothing but time eases the pain.

From earliest times, chiles, tomatoes, and fish have added nutritional elements to the Mexican diet, which is based on corn and beans. All the podlike chiles, except the habanero, are varieties of Capsicum annuum, a plant unrelated to the one that produces our own black peppercorns.

With beans (protein and carbohydrates) and corn (protein, carbohydrates, and calcium) the addition of chiles makes the Mexican diet one of the world’s healthiest. Chiles, if eaten fresh (not dried or canned), provide the highest vitamin C content, calorie for calorie, of any food. They also contain unusually large amounts of other vitamins (especially A) and of essential minerals (like chromium).

Fresh Chiles

Poblano—A mild, triangular-shaped green chile used mainly for chiles rellenos, about five by three inches. An acceptable substitute is the California or Anaheim chile. The use of bell peppers in making chiles rellenos is the mark of an amateur.

Serrano—A very hot green chile, usually one and a half inches long, especially good fresh in guacamole and salsa cruda.

Jalapeño—A hot to very hot, plump green chile, one to two inches long. It is used more in Tex-Mex than in Mexican cooking and more often from a can than fresh.

Cayenne—A green chile, three inches long, used as a substitute for jalapeño or serrano.

Dry Chiles

Ancho—The most common chile used in Mexican cooking, it is the ripened, dried chile poblano turned deep reddish brown and wrinkled. It ranges from mild to hot and is usually ground and used as a sauce base.

Chipotle—A light-brown chile, it is the jalapeño ripened, dried, and smoked with wrinkled skin. Mild to hot, it is used mainly to season soups. The smoking process gives it a very distinct taste and smell.

Pasilla—A very hot, six-inch-long, brownish-black chile, which is chile chilaca in its dried, ripened form. Toasted and ground, it is used for making sauces.

From Chiles to Sauce

To make your own fresh salsa cruda for the table, peel a fresh, ripe tomato (it helps to drop it into boiling water for about ten seconds), then grind it with a chile serrano on your molcajete and add minced onion, garlic, and cilantro. Salt to taste.

A fine cooked salsa for your enchiladas is almost as easy. Boil some chiles anchos until soft, remove skins, and puree in a blender. (If you want a mild sauce, open the chiles and scrape out the seeds.) Heat a small amount of flour and oil paste for thickener in a pot. To this add ground comino seeds and garlic, the liquefied chiles, and a dash of oregano. Simmer for about half an hour. ¡Rica!

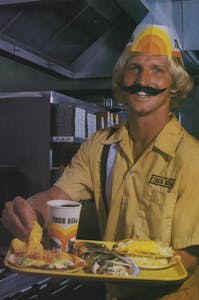

In the days before Taco Bell: chili from carts in turn-of-the-century San Antonio. Today Gebhardt’s chili con carne rolls off conveyor belts.

Then: Tex-Mex

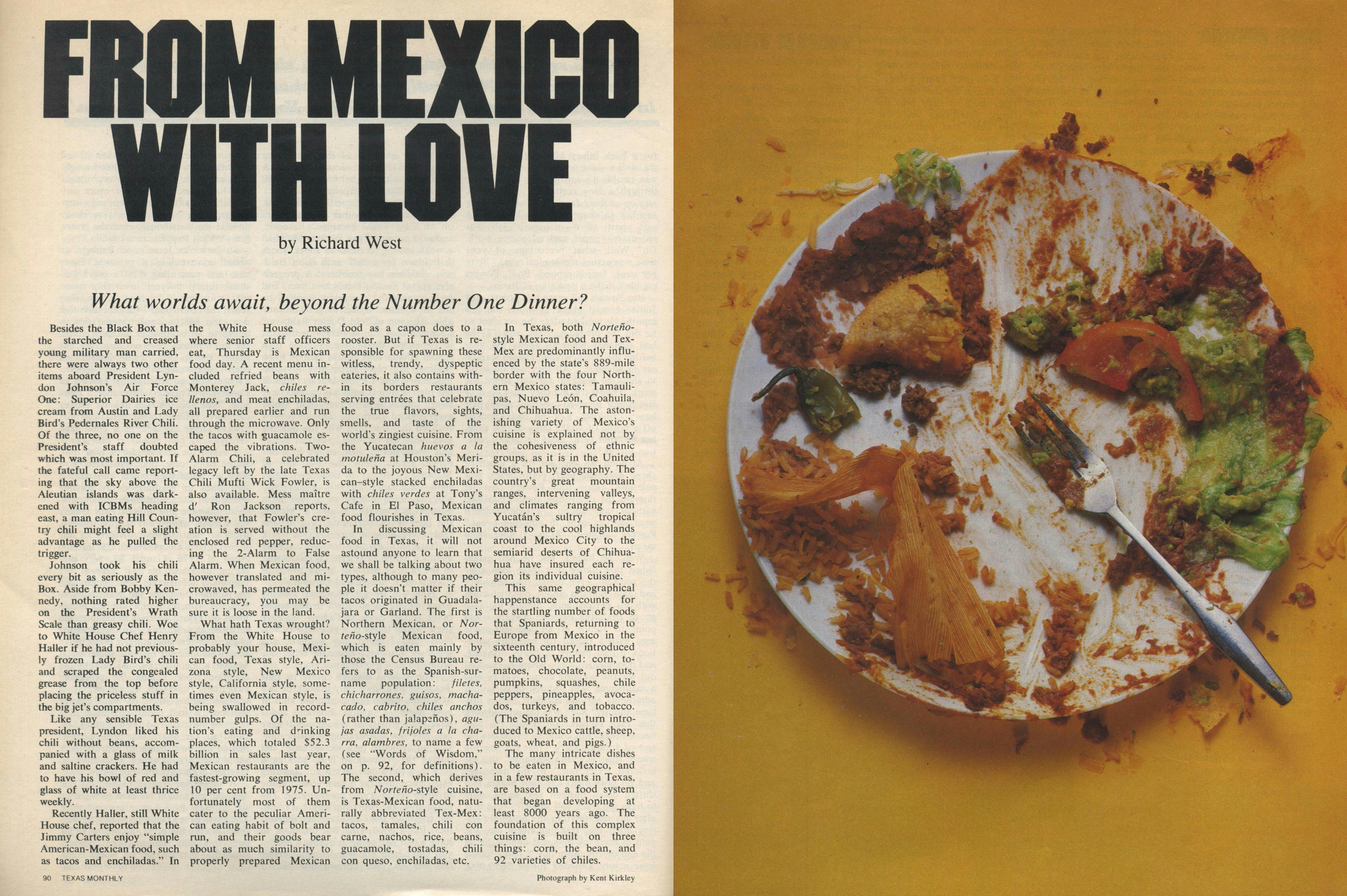

How Tex-Mex came to be is a question of debate. It varies from its progenitor by necessity, because a lot of the essential ingredients in Norteño-style food have not been available to Texas cooks, who have in turn ad-libbed. It has also evolved—and some would say declined—in restaurants in response to hungry, hurried gringos willing to settle for less authentic flavor.

The standard Tex-Mex foods (tacos, enchiladas, rice, refried beans, tamales)—and newer additions, like chiles rellenos, burritos, flautas, and chalupas—existed in Mexico before they came here. What Texas restaurant cooks did was to throw them together and label them Combination Dinner, Señorita Special, Regular Mexican Dinner, Extra Special Mexican Dinner, and the hallowed Number One. In so doing they took a few ethnic liberties and timesaving shortcuts. For example: Tex-Mex tacos as we know them contain ground, instead of shredded, meat. And chile gravy is most often out of the can, instead of being made fresh with chiles anchos and special spices. Fresh chile gravy, which is unmistakable from canned, is one cue that a restaurant is taking special care in the kitchen. Fortunately, a few Texas restaurants are taking the time.

Marfa’s Old Borunda Cafe, established in 1887, is the first Mexican restaurant in Texas and still sells semi-divine food. The present owner and kitchen supervisor, Carolina Borunda Humphries, now seventy, began making tortillas and enchilada sauces at her mother’s cafe in 1924 on a Sears and Roebuck wood stove, purchased in 1920 for $44. She is now cooking on the Old Borunda’s third wood burner, a $60 1961 vintage.

The mesquite wood brought in from Fort Davis has been slowly cooking the same items—including Carolina’s specialty, chicken tacos—for seventy years. Mrs. Humphries showed us a 1938 menu that featured the Special Dinner: two enchiladas, two tamales, one taco, chili con carne, guacamole salad, coffee or milk for $1. Today for $3.30 you get the same, except beans (fried the right way in pure lard) instead of guacamole, and you pay extra for your drink.

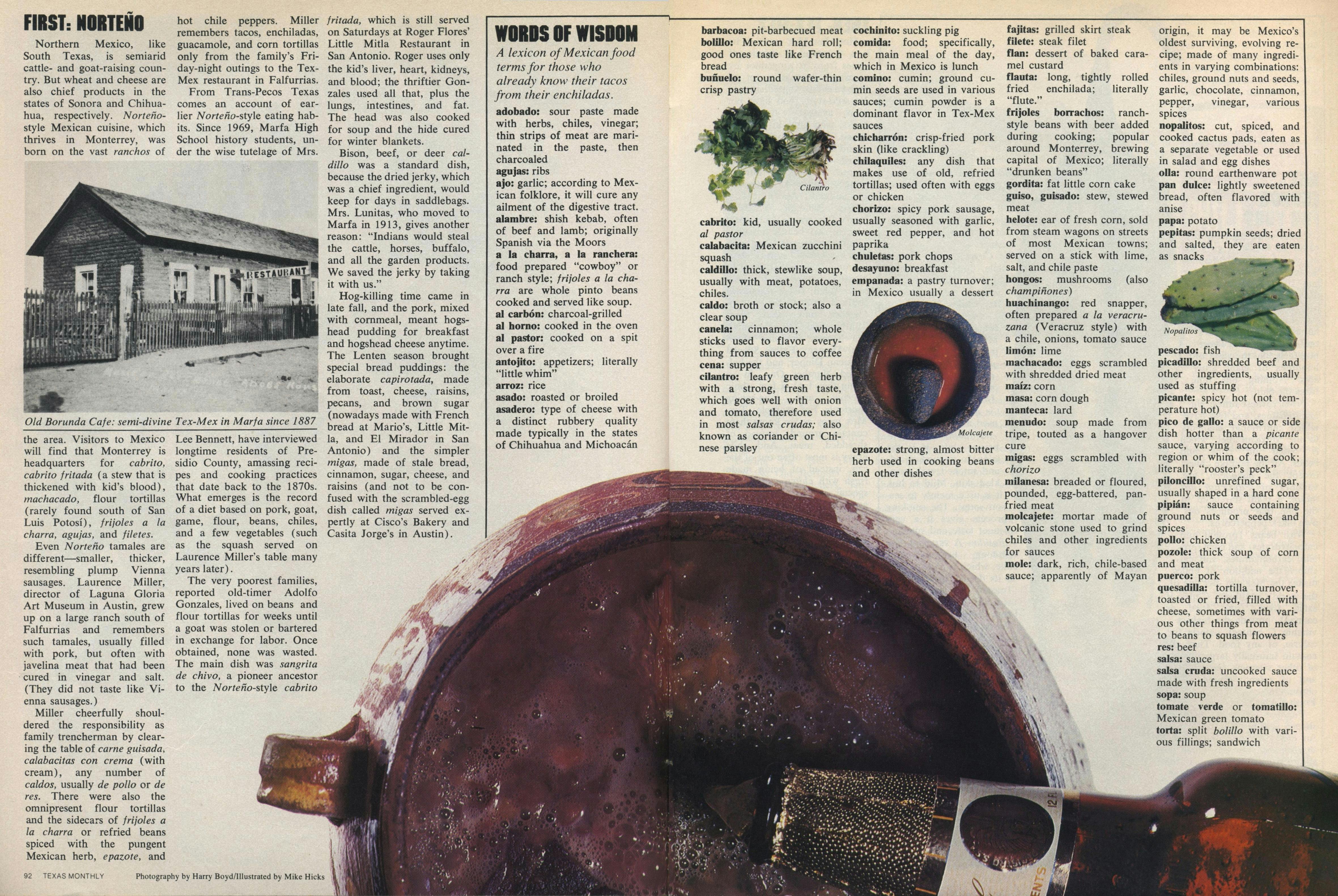

During the late 1880s when the Old Borunda was feeding Marfa ranchers, San Antonio’s famous “chili queens” were enthusiastically selling chili con came, tamales, enchiladas, chiles verdes, frijoles, menudo, and tortillas from their open-air booths in Military Plaza, site of the city’s first permanent Spanish settlement in 1722. The women arrived at dusk pushing handcarts loaded with paraphernalia. They set up chili stands consisting of three tables in a U-shape. The food, usually precooked, was warmed over a brazier and kerosene stove. The tabletops were about ten-feet-long planks on sawhorses, covered with red-and-white checkerboard oilcloths and set with lanterns, vases of paper flowers, and red clay bowls with oregano and chopped onions for menudo fanciers. Chili cost visitors like Sydney Porter (O. Henry), Robert Ingersoll, and William Jennings Bryan a dime and was served with bread and a glass of water. The ladies worked until dawn when the day-job vendors arrived to hawk everything from vegetables to songbirds in wicker cages.

The few remaining chili queens were finally ordered off the city’s plazas in 1939 for health reasons by Mayor Maury Maverick, Sr., but their influence had been great. At the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, there was a booth called the “San Antonio Chili Stand.” Three years later a San Antonio German, William Gebhardt, concocted the first commercially prepared chili powder, and in 1908 the first can of Gebhardt’s Eagle Chili Con Carne rolled off the conveyor belts.

In 1900, San Antonio strengthened its claim as the Mexican food capital of Texas when O. M. Farnsworth opened the state’s second Mexican food restaurant, the Original Mexican Restaurant at 117 Losoya (now Broadway). No flotsam drifted into the Original, for Farnsworth demanded his customers wear coats and ties before being served. The Original’s 1911 menu makes you cry. For 25 cents, you could pack away tamales, chili con carne, frijoles, corn tortillas, enchiladas, sopa de arroz, and coffee.

If eating Mexican food in a coat and tie meant needless discomfort, a few years later folks could hike a block down Losoya to Mitla (est. 1923), operated by Rogelio Flores, the father of Little Mitla’s Roger, or over to the Casa Blanca at the corner of Houston and Santa Rosa, or venture to Westside San Antonio to the Mexican Manhattan.

Meanwhile in small Texas towns a tradition was beginning in a few Mexican homes that still exists today, the fondita, or “small inn.” A Mexican woman, well known in the community for her breathtaking morsels, put several tables in the front room of her house and at Sunday noon cooked family-style Mexican food for Anglos.

Mrs. Felix Tijerina, owner of Houston’s oldest Mexican restaurant, Felix’s (est. 1928), remembers her mother setting up four tables in their home in Pleasanton to feed famished gringos in 1919. The four tables groaned under Sonoran-style beefsteaks rancheros, tamales, puerco en pipián, carne asada, handmade corn tortillas, menudo on weekends, and coffee. Next might come venison and arroz con pollo, then pan dulce and buñuelos.

Many of today’s established restaurants began as fonditas, examples including San Antonio’s La Fonda (on North Main), and Austin’s La Tapatia and El Gallo. A few continue in the noble tradition of serving from their homes: Z. Z. Zamora’s and The Last Concert in Houston and the Old Borunda Cafe. Unfortunately, Allie’s, a well-known fondita in Kingsville, recently closed its doors.

![From Mexico w Love - 0004]() Flat is Beautiful

Flat is Beautiful

Since some anonymous genius had the inspiration to cultivate a few rows of wheat south of the Caspian Sea some 10,000 years ago, the world has been “civilized.” Man’s grocery list shifted from mainly meat to cereal grains, and cultivation of a dependable foodstuff such as wheat or barley led quickly to irrigation, bread, beer, farms, soil-fertility rites, and finally villages.

Recent diggings suggest that rice was grown in Thailand as early as 4000 B.C. and spread north and west to China and India soon after. Meanwhile in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley, Indians had been raising corn since 6000 B.C. When Cortés and his band of Spaniards arrived in 1519, they were delighted to find this Indian “maize” and to carry it back to the Mediterranean, where it became a staple in Portugal, Italy, and Spain.

Mexican corn comes in rainbow colors—yellow, red, bluish green, purple—but it is the white kernel that makes Mexico’s daily bread, its pasta, its jack-of-all-foods, the tortilla.

Mexicans have always made tortillas from a corn dough called masa. The white kernels are scraped from the cob and boiled in water with a bit of charcoal or lime added to loosen the skins. The skinned, blanched kernels (nixtamal) were then mashed with a stone roller (mano or metlalpil) on a metate, a three-legged, sloping table made from volcanic rock. The resulting masa dough was kneaded into small (about two-inch) spheres, slapped into, thin round cakes, and dry-cooked on a hotplate-like stone called the comal for two minutes.

Current practitioners of hand-patted tortillas take about 40 to 45 pats to do the job. Unless you are a born tortilla patter, you will find this apparently easy task impossible. The pesky ball of dough sticks to your hands, falls on the floor, doesn’t flatten out, and generally acts ornery. Mexican cooks who make their own tortillas today usually buy packaged masa harina (dehydrated masa flour) and add water or buy fresh ready-made masa, sold by the kilo in Mexican markets. Most buy the finished product from the local tortillería.

If you want to make fresh tortillas, purchase Quaker brand masa harina, the best dehydrated masa available in the United States, and a tortilla press, preferably with a plate six and a half inches in diameter. In a bowl combine one cup masa harina with 2/3 cup warm water and ½ teaspoon salt and work the mixture until it forms a soft dough. Roll a piece of dough into a walnut-sized ball and flatten it on the tortilla press between two sheets of waxed paper to form a round cake about four inches in diameter. Carefully lift the tortillas from the paper. (If it sticks, the dough is too moist. Return it to the bowl and work in a little more masa harina.) Lightly grease a griddle, preferably cast iron, and heat each tortilla about a minute on each side. Yields twenty.

![From Mexico w Love - 0003]() The Mexican Can-Can

The Mexican Can-Can

What the folks in Peoria think is Mexican food is not even close.

A lot of Americans seem to think that eating is a waste of time. That being the case, franchisers were all too ready to combine that bent with a newly formed taste for the flavors (or in this case, is it flavor?) of Tex-Mex food. It all began with El Fenix (est. 1918), followed in 1940 by El Chico—both of Dallas. Now there’s a Taco Time in Eugene, Oregon, a Taco Tico in Wichita, Kansas, a Tippy’s Taco House in Philadelphia, and . . . you get the picture.

In January 1966 there were six Taco Bell outlets; eleven years later the largest Mexican food chain in the country grossed $170 million from 759 locations, and they are still growing. Monterey House, starting as a takeout operation in Houston in 1954, now has 62 units, an annual gross of $28.6 million, and ranks ahead of Stuckey’s and Nathan’s Famous Hot Dogs of New York.

Where restaurant proclivities go, can supermarket preferences be far behind? Quick Frozen Foods Newsletter reports that after pizza, Mexican food is the leading ethnic category in frozen-food sales, accounting for 37 per cent of the $234 million market last year.

The typical Tex-Mex menu has these eight items: tacos, tostadas, burritos (the new favorite, outselling tacos), tamales, enchiladas, taquitos, and, yes, chili burgers and chili dogs. I quote from a significant article in Fast Food magazine: “There is very little cooking done at the restaurants. They receive canned enchilada sauce, canned hot sauce, canned taco meat, and canned chili con came sauce. . . . El Burrito of Birmingham, Alabama, can put together an entire Mexican meal in sixty seconds, working from steam tables and steam cabinets. . . . No knowledge of Mexican food is needed by the franchisee.”

Where does this leave the small owner trying to retain a semblance of authenticity? “It’s the old story of independents versus the giant chains,” said Tom Gilliland of Austin’s San Miguel. “Pancho’s uses a cheese substitute costing them 70 cents a pound and we buy Muenster at $2.65 a pound.” Robert Vivion of Fort Worth’s Caro’s feels the bite with chile pods. “We buy 25-pound boxes of chile pods that we grind here in the kitchen—they’ve gone up to $94 a box.”

Despite all that, Mexican food restaurants have the highest profit return after steak houses. So the food will be around for awhile, whether your style is Heublein’s (Kentucky Fried Chicken) new chain of fast feeders called Zantigo, or the family-run fondita down the street that grows its squash and herbs in the garden behind the house.

![From Mexico w Love - 0002]() Behold the Bean

Behold the Bean

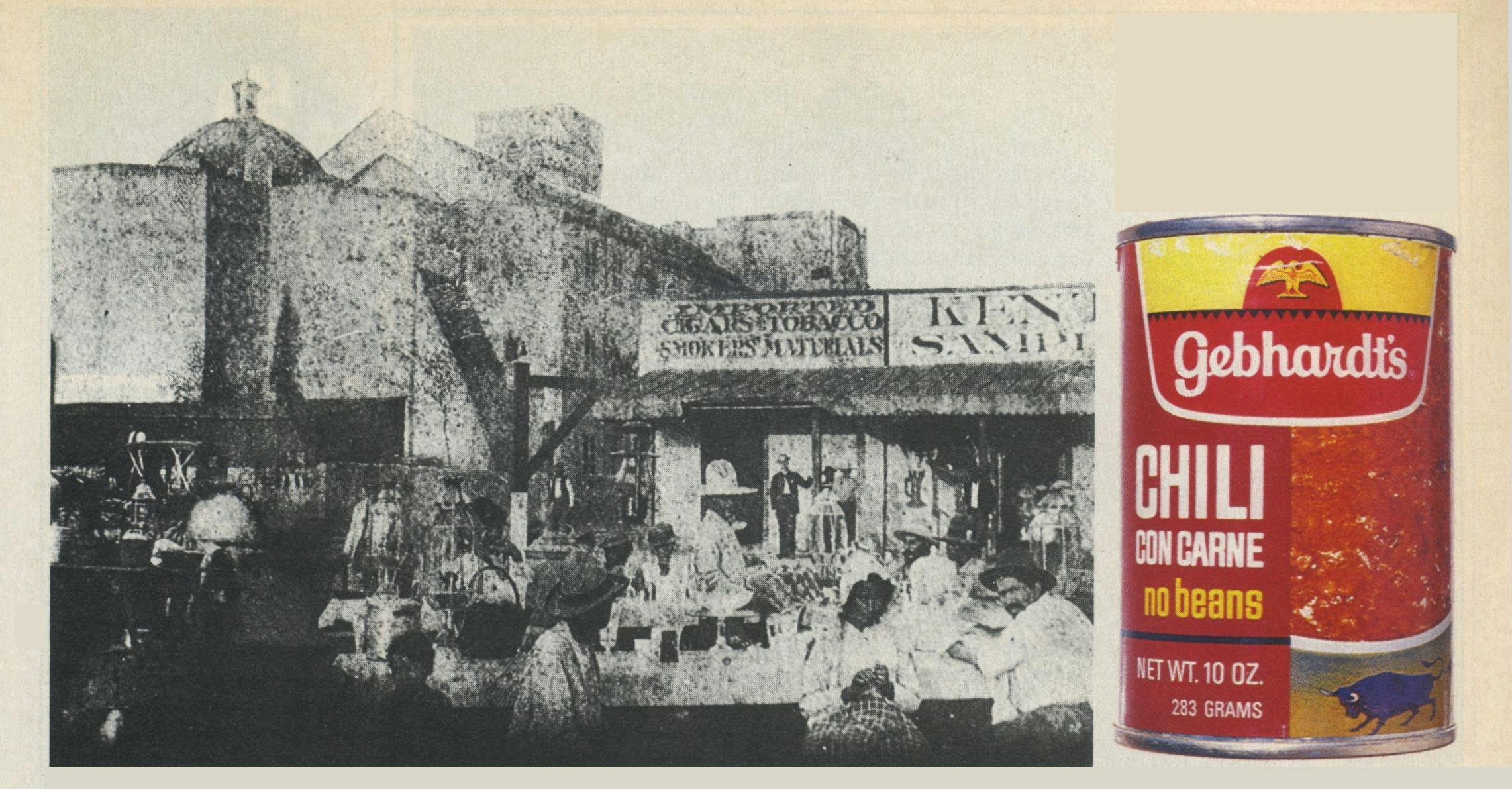

By the time the Spanish set foot in the New World, the Aztecs had already perfected the cultivation of beans. The beans that filled the baskets of Aztec merchants—red beans, green ones, pink, yellow, brown, black, ivory, and speckled beans—would have made an Aggie proud. They even had beans that the Spanish had never seen before, like lima beans (from Peru), string beans, and shell beans.

Beans have been cultivated in Mexico since at least 6000 B.C. The shrewd person who discovered you could dry and store the little legumes got a lot of generations of Mexicans through hard times.

Along with the corn tortilla, beans have been a constant staple of the native diet. Without the amino acids beans contain, corn could not provide the complete protein humans need. Eaten together, corn and beans compensate for the small amount of meat protein available to the general population.

The Aztecs prepared beans much as we make them today: boiled in clay pots for soup or mashed and flavored with chiles and spices. While the Aztecs taught the Spanish a thing or two about growing beans, it wasn’t until the conquistadors introduced the natives to lard that the subsequently cherished dish, frijoles refritos (refried beans), was invented.

If you are interested in sampling the authentic flavor of Mexican-style beans, let us suggest a simple recipe from J. Frank Dobie, who called himself “a kind of frijoles man”: Wash a pound of pinto beans; soak them overnight. Add water to cover beans generously. Also add a cube of salt pork. Cook until tender, adding water as necessary and salt to taste. The end result is a bean soup.

For refried beans: mash half or all of the leftover beans. Heat some lard until very hot in a skillet and add the beans. Stir until beans are dry and thick.

Now: The Restaurants

DALLAS

In Dallas, Mexican restaurant history began with the arrival of Miguel Martinez from Hacienda del Potrero, Mexico, in 1911. After being laid off the track-laying crew of the Dallas Street Railway Company, Martinez was a dishwasher in the Oriental Hotel (where the Baker Hotel is today). He studied the food business and in 1918 opened a one-room, one-man place called El Fenix at McKinney and Griffin. In 1975, with total sales of $15.6 million, the fourteen still-family-owned El Fenixes ranked eighty-ninth among the nation’s restaurant chains.

But a bigger Dallas success story began eight years later when an energetic, bustling lady named Adelaida Cuellar and five hungry sons opened a tamale stand at the 1926 Kaufman County Fair. With her sons hustling tamales and doubling as mariachis, Adelaida opened Cuellar’s Restaurant in Kaufman the following year, and a second soon after in nearby Terrell. Years later, after selling out their El Charro restaurants in Oklahoma City, the Cuellars opened the first El Chico Mexican Restaurant in Dallas in 1940. Although the Cuellars’ Els proved the biggest successes, connoisseurs of early Dallas Mexican food favored two other places, now gone: the Mexico City Cafe and, best of all, El Poblano.

El Chico’s influence can’t be measured just in terms of its own profits or proliferation. At last count, nine restaurant owners or influences of Dallas’ Mexican food at one time washed, waited, cooked, or managed branches in Mama Cuellar’s corporation, including the legendary chef, Gordon Montez, who is responsible for many Tex-Mex dishes he developed as chef at Austin’s El Charro (1940) and El Rancho (1950s) and at Casa Dominguez (1960s) in Dallas.

All these restaurateurs express gratitude to the Cuellars, but, in chorus, emphasize they learned as much what not to do as what to do. “I worked at El Chico in Longview for six weeks or so,” said Montez, “but quit when I discovered all I had to do was open cans and heat up already-prepared food.”

These same El Chico alumni and critics agree that the person most responsible for revitalizing Dallas’ interest in Mexican cuisine is an ex-dishwasher, shineboy, busboy, and waiter, Pete Dominguez. In 1963, when he opened Casa Dominguez on Cedar Springs, eating Mexican food in Dallas was about as exciting as having a date with Merv Griffin.

Dominguez borrowed $1500 and opened his restaurant with “Austin-style Mexican food,” based on chef Montez’ recipes and Dominguez’ own food memories from waiting tables at the Capital City’s El Patio and shining shoes on the sidewalks of Sixth Street. Casa Dominguez caught the eye of sportswriters, football team owners (Lamar Hunt, Clint Murchison), and UT fans—Pete has a well-known penchant for Darrell Royal and the Texas Longhorns. Soon his weekly use of 5 pounds of cheese had risen to 35 pounds daily. Now Pete Dominguez Enterprises runs a small gastronomic empire of four Dallas restaurants and one in Houston.

Dominguez says “Austin-style” Tex-Mex is milder and less greasy. I cannot agree, but it’s a good gimmick and it worked. In the early sixties his Tex-Mex was better than average but, more important, his restaurant became a place to be seen. The food remains best at the Cedar Springs location. Dominguez claims to have introduced beans and cheese nachos and guacamole nachos to Dallas. (One thing must be made clear at this point. Of the 70 or so Mexican food restaurant owners in Texas whom I interviewed—and whose food I ate—63 stated seriously without qualification or eye-twinkle that (1) “We have the best [fill in the blank] in town”; and (2) “The [fill in the blank] is our own creation. Until we opened, no one had [fill in the blank] on their menu.” “Mon Dieu!’’ became my stock reply.)

Now that Dominguez is established and rich, and Ojeda’s and Herrera’s are old hat, the Dallas Tex-Mex hubbub—much to the dismay of its faithful old customers—centers on the Escondido, owned by the Herrera brothers, Tomas and Juan (no relation to the Maple or Lemmon Herrera’s). It’s not so much the food at Escondido, but the shantytown ambiente that draws crowds of Dallas swells. Besides, any place that calls a dish “Sotelo’s,” after the air-conditioning man who did repairs during the lean years and told the Herreras they could pay later, deserves all the play it can handle. Chef Tomas, called “the Ben Franklin of the kitchen” by brother Juan, has done a good job of forgetting lessons learned earlier in his career in franchise kitchens. His special treat is the Herrera Brothers Special, two bean-and-meat-packed sour cream enchiladas, meat taco, and guacamole chalupa.

If Pete Dominguez started the renaissance in Dallas Tex-Mex restaurants, Mario Leal took a bigger gamble five years ago with Chiquita. Were Dallas diners ready to go Norteño? Would they jump at chicken en mole Puebla style or react like vapid titmice and fly back to familiar Tex-Mex nests? Leal gambled and it paid off not quite as handsomely as for Dominguez, but he was playing a tougher game.

The specialties at Chiquita reflect the culinary expertise of his now-departed chef, Barnie Gonzales, who is the resident Texas master of Norteño-style beef, chicken, and pork dishes. Sadly, Leal’s filetes milanesas, carnitas adobadas, and chuletas a la Mexicana need Gonzales. His fish dishes, however, are the best in North Texas, particularly the pescado blanco marinero (white fish with spinach stuffing topped with an oyster and shrimp sauce).

One question I asked almost all restaurant owners is, “Where do you eat Mexican food on your day off?” The undisputed winner in Dallas was Barnie Gonzales’ Guadalajara, which is in an even more disreputable part of town than the Escondido. One of life’s rare triumphs occurs when you can introduce friends to a great restaurant in an undiscovered part of town—in this case, near the corner of Ross and Hall streets. Here is your chance.

Gonzales’ magic, which worked wonders in Leal’s fancy Oak Lawn digs, performs just as well in this cavernous building next to the Smart Barber Shop. Like Chiquita’s, Gonzales’ specialties are Norteño-style meat dishes but at half the price. His most impressive offering, the carne asada a la Tampiqueha (steak seasoned and broiled by a recipe developed in Tampico), is the most expensive item at $2.95. His huge menu, the size of Moses’ stone tablets, offers the most authentic Mexican breakfasts in Texas north of Austin: machacado con huevos, nopalitos con huevos, nopalitos con chorizo, chilaquiles con queso. Sissies and the fainthearted will find predictably good Tex-Mex dishes under “Combination Dinners.”

I have not had a bad meal at the Guadalajara. If your mouth is lined with asbestos, an eye-watering thermal experience is the filete curado con piquín y ajo, a perfect choice ribeye cured with garlic and chiles piquines, the smallest and hottest of the capsicums. (Major Tom Armstrong of the King Ranch used to carry piquines around in a sterling silver snuffbox and eat them like popcorn.) Try the chiles rellenos, too; they are surpassed only by those at Adelante. The Guadalajara is open from noon until 3 a.m. and is a favorite after-hours gathering place.

Maxine Oesterling’s small elegant North Dallas restaurant and gift shop, Adelante, not yet two years old, presents the most carefully prepared Mexican food in town. If there were such a thing as Mexican haute cuisine, this would be it. Only San Miguel in Austin serves similar food. Adelante’s dishes, such as the green chile quiche and the Guadalajara (grilled beef strips simmered in white wine, onions, peppers, tomatoes) appeal to your aesthetic sensibilities as well as to your palate. Generous loads of Monterey Jack and fresh ingredients (there’s not a freezer in the kitchen, and only the jalapeños come from a can), combined with the skills Maxine learned from her mother’s Mexican family, insure the excellence that emanates from the kitchen.

It is typical for Mexican food restaurants to create minor sensations when they first open. They may continue to excel, or at least not to disappoint, in one or two offerings and usually they maintain a contingent of faithful customers, but more often than not they flash in the pan. Not true of Joe Navarro, Jr.’s El Taxco, which for thirty years has been worth going back to. The chicken enchiladas, guacamole salad, and tacos are excellent, and the usual Tex-Mex is always reliable. El Taxco remains a good port in a storm.

Raphael Carreon is Dallas’ latest Mexican food poor-boy-made-good. Crowds at Raphael’s are such that elbow room is down to a vanishing point and the decibel level registers as high as a Led Zeppelin concert. The reason for the claustrophobia and aural discomfort is that the food is excellent and moderately priced. The spicy enchilada en mole topped with Monterey Jack is an ideal blend of taste and savvy as is the carne Tampiqueña. Barely two years old, Raphael’s success has spawned his second business, Alamán’s, which opened in December.

HOUSTON

Even though Houston is just an overgrown East Texas town on the fringes of the Piney Woods it is the state’s largest city with the highest percentage of demanding food seekers. So it’s not too surprising that here one finds the widest spectrum of Mexican cuisine. Houston is the place to go with time and an appetite.

The first place Houstonians will tell you to go is Ninfa’s. At this particular point in time no other Texas restaurant dictates the dining-out habits of so many of its city’s inhabitants. Ninfa’s is also a favorite topic of conversation among Mexican food fanciers not just in Houston but all over the state. The Laurenzo family, led by Mama Ninfa, admits they are baffled why their original Ninfa’s, set in a woebegone neighborhood southeast of downtown in the warehouse district, averages 700 customers for supper and 400 for lunch; or why the new Ninfa’s on Westheimer brings in 1000 for supper, 600 for lunch. That’s seven days a week.

All the entrees at Ninfa’s, Tex-Mex and Norteño style, are well prepared, and the service is unflagging. Nine times out of ten, a mention of Ninfa’s is followed by “tacos al carbon,” the house specialty. That’s the hot product, but the Tex-Mex dishes make up 60 per cent of the sales, followed by tacos al carbon and the excellent flautas de pollo. Like Doneraki, the city’s other excellent Norteño-style restaurant, Ninfa’s selection of charbroiled meat dishes is cornucopian. Try the substantial agujas or the flamboyant chilpanzingas (deep-fried corn tortilla stuffed with ham, cheese, and pico de gallo, then covered with sour cream and cheese). Don’t be surprised if you detect an Italian influence—olive oil, parmesan and mozzarella, more garlic—in many of the recipes; this is due to the influence of Ninfa’s late husband.

For another gratifying Norteño-style Mexican food experience, plunge into the menu at Doneraki. Victor Rodriguez and his family studied and consumed Norteño cuisine in Monterrey. Like Ninfa’s, Doneraki features tacos al carbon, but Victor goes a step farther and also prepares meats al pastor. His tacos de carne deshebrada (shredded beef) are faithful to their counterpart in Chihuahua, steak capital of Mexico. At each table are small bowls filled with diced onions and cilantro. All dishes are accompanied by frijoles a la charra and pico de gallo. Victor has even improved on nachos. He fries the beans and cheese together, then tops the tostada with more cheese, usually asadero or Monterey Jack (either an acceptable substitute for Mexico’s finest cheese, queso Chihuahua, still made in the Mennonite colony near Chihuahua City). Now picture this: all these delicacies are served in large rooms around a patio and fountain furnished with dazzling white wrought-iron tables and chairs from Saltillo.

Two blocks down Navigation from Ninfa’s is the Merida, Texas’ best Yucatan-style Mexican food. The state of Yucatan, which is part of the peninsula that juts into the Gulf of Mexico 707 air miles south of Houston, has the most distinctive cuisine in Mexico. When you go to the Merida, first admire the wall-length mural of a Mayan sacred city. Then find the menu—Platillos Yucatecos—and pick out the familiar Spanish words. Most people start stumbling after “tacos,” “arroz,” and “frijoles.” What are cochinita and panuchos? The first is pork; the second, a soft puffed pastry. Try cochinita pibil for a taste of Yucatecan mastery; it is young pig spiced with herbs, wrapped in banana leaves, and barbecued in the traditional pib or Yucatan pit. Merida omits the pit and the traditional sour Seville oranges, but you will forgive them for these flaws in authenticity. Panuchos are a cousin of the tortilla stuffed with fried black beans, then topped with pork, onions, lettuce, tomato, and cheese. The Merida also serves a Yucatecan breakfast dish, huevos a la motuleña (ranchero-style eggs served with a delicious topping of ham, English peas, and cheese).

Houston has two old reliable Tex-Mex restaurants. Spanish Village has Christmas-tree lights, colorful ladder-back chairs, alfresco dining, and one of Texas’ best waiters, Larry Castellano, readily identifiable by his customary Hawaiian shirt. Try the Deluxe Dinner and while overindulging enjoy the street life. Bertha’s is a Houston legend. No one takes greater care in food preparation, or in the cleanliness of the kitchen, than the owner, Mrs. Bertha Robinson, and she will conduct a tour of the facilities in an instant. Three of the best things on the menu are tostadas compuestas, carne guisada, and entomatadas. Ask for her party specialties, which she will prepare given a day’s notice.

There are several obvious reasons why The Last Concert is the unique Mexican restaurant in Texas: there’s no sign; no advertising in 27 years of business; no menu; a locked door, which waiter Richard Gill or manager Tom Gonzales opens only after peeking at you through the curtain; an outdoor patio chronicled by Larry McMurtry in Terms of Endearment; and a beautiful smoked-glass Art Deco bar. It’s harder to find than a true love or a good auto mechanic. The original six-burner stove still turns out only three items: Small, Large, and A La Carte. Get the Large (one taco, two enchiladas, chili con queso, chalupa, rice, and beans), because the food is good. And don’t forget to thank the wonderful owner, “Mama” Elena Lopez, who lives next to the patio.

Zaul Z. Zamora, wife Norma, and new baby, Zelina Zena, live upstairs at Z. Z. Zamora’s, Houston’s newest fondita. The chief benefit is that Norma is never far from the stove. I’m sure you’ve heard a watched pot never boils; it also means the chicken enchiladas verdes topped with sour cream and cheese are never bad. It is one of Houston’s best dishes, helped along by Mrs. Zamora’s large supply of fresh-grown cilantro out back. Zaul (his sisters are named Zolia, Zulema, and Zeyla) has a nice vegetarian menu for noncarnivores and very respectable breakfast dishes on a third menu. As far as I know, he’s the only three-menu man in town. The Z’s are a family tradition and the next daughter’s name is already chosen: Zophia.

SAN ANTONIO

San Antonio is where Mexican food restaurants in Texas took hold and it is where good Mexican food still survives. According to the 1970 Census Bexar County is 68.5 per cent Mexican American. An obvious corollary to that fact is that San Antonio has more Mexican restaurants, although many are the takeout variety on the city’s west side, than any other Texas town. There is another factor in San Antonio’s favor: no other large Texas city can match its relaxed, peaceful rhythm, and nowhere else in the state combines this casual pace with good Mexican food quite like San Antonio’s famous Riverwalk.

Casa Rio, the only business on the river until fourteen years ago, is something of a patriarch among Mexican food restaurants. It has had its good times and bad. For years, San Antonians bemoaned the death of good food at this charming riverside restaurant with the same seriousness they would the collapse of the democratic ideal. The original owner, Alfred Beyer, who opened Casa Rio in 1946, had placed it in the hands of a man more interred in excursions and paddleboats than in the menu. When Beyer’s son-in-law, Bill Lyons, Sr., took over as owner he hired Franklin Hicks from La Fonda to make things right again. Hicks, now a partner in the enterprise, faced an overwhelming task, but he manfully persevered. These days Casa Rio is not only serving 48,000 to 50,000 people a month during June, July, and August (2200 to 2500 meals a day) but also has reinstated a hearty chicken-stock enchilada gravy; eliminated all American food items; continued making tortillas and tamales on the premises; and added a good sangria.

The bestseller—and the best dish is carne asada, well seasoned, generous tender. There are no exotic menu offerings, strictly Tex-Mex meals, served for moderate prices on land or for $8.75 per person on barges that cruise the river with musicians and bar.

Time was when strollers on the river passed La Paloma del Rio without a backward glance. But Marie Sherman arrived in November after living, cooking, studying food, and running restaurants for seven years in Mexico City. She makes San Antonio’s only serious attempt at classical interior Mexico cuisine. Her huachinango Veracruz, Mexico’s most famous fish dish, is perfect, the tomato sauce well seasoned but not ruthlessly picante. La Paloma del Rio also dishes up authentic Mexican sopas: pozole, tortilla, black bean, and tlalpeño (vegetable broth named after Tlálpan, a town on the outskirts of Mexico City). And one more thing: wonderful guacamole made with lime, cilantro, chopped serrano chiles, and tomatoes.

In 1951 a remarkable man, Pete Cortez, opened Mi Tierra, a 24-hour, popular postmidnight gorge palace near San Antonio’s produce market, and now owns most of the block. Mi Tierra and the market area have been spruced up, and the Cortez family plans outside dining to complement the fancy new esplanade.

Chicanos early in the evening enjoying hot chocolate and pan dulce, boisterous Anglo crowds later on, freelance mariachis, and year-round Christmas decorations (punctured beer cans with lights inside strung around the ceiling) have always been part of Mi Tierra’s mystique. The place is more of a Tex-Mex landmark than a model of fine cuisine. The food is filling, rather than exceptional, but you can’t miss with the better-than-the-average steak ranchero or chicken enchiladas en mole.

Mario’s, just west of Mi Tierra across Interstate 35, which divides Westside and downtown San Antonio, has the most interesting menu in town.

It is supervised by Mario Cantu, the city’s controversial Chicano activist whose energies overflow to his restaurant. What started as the small “M. Cantu Cafe” now seats 300 and features dishes from all parts of Mexico. Best is tenderloin of beef tips sautéed in chipotle chiles and topped with asadero from Michoacán. From Puebla comes a good chile relleno; from Oaxaca pechuga de pollo en mole and a great appetizer, hongos con chorizo.

El Mirador has captured the imagination of San Antonians much as have Ninfa’s in Houston and Escondido in Dallas, though on a smaller scale. It opens early—6:30—with good Mexican breakfasts. The tempo quickens about 11:30 a.m. when downtown businessmen begin lining up outside for San Antonio’s best cabrito on Tuesdays, the bestseller, steak ranchero, on Wednesdays, and the excellent paella on Thursdays. The place closes after lunch to recover from the noon onslaught.

Saturday is the day to try El Mirador’s most famous creation—an authentic version of the Aztec soup caldo xochitl. The ingredients would fill a page, and it takes hours for Mrs. Mary Treviño to prepare; it costs $1.25. Because of this one dish, this small ten-year-old restaurant should be added to San Antonio’s long list of historic shrines.

Far southside San Antonio’s best restaurant, the Pan American, opened in 1939 on a $1.50 grocery-list investment for masa, meat, and corn shucks and four tables in founder Lucinda Salazar’s home. Tamales remained her specialty through the forties, and the business was known as Pan American Tamale Headquarters in those days. Now the Salazars can seat 600 around the enclosed patio and fountain, and the tamales are still wonderful. The Salazars’ chicken enchiladas verdes and any item with mole sauce come highly recommended.

AUSTIN

For many people, Austin is more closely identified with Mexican food in Texas than San Antonio. When it comes to Mexican breakfasts, it is certainly the capital of the state. Here also is San Miguel, the state’s only restaurant with an entire menu devoted to Mexico City and other interior Mexico entrees; here is El Rancho, whose fanatical supporters and efficient service are legendary; and here are the haunts that have addicted thousands of UT students and Austin visitors to basic Tex-Mex: El Matamoros, La Tapatia, Spanish Village, El Gallo, El Patio.

Cisco’s Bakery in East Austin, open since 1949, is a hangout for neighborhood Chicanos as well as Anglo politicians and UT students and academics from west of Interstate 35, It is owned and operated by Rudy Cisneros, who has struck it rich not on pan dulce but on huevos rancheros, migas, and huevos con chorizo. Count on Cisco’s always being a little smoky and avoid the place on Sunday mornings after UT football games, when the pigskin crowd overwhelms the regulars. The other East Austin cafe, Joe’s Bakery, has recently remodeled and serves authentic Mexican breakfasts and a variety of pan dulce to a predominantly Mexican American crowd.

The other two good breakfast places are south of the Colorado River. La Reyna Bakery serves very good huevos rancheros and huevos con papas, but it and the other bakeries are outshined by Casita Jorge’s. Jorge Arredondo and his family serve standard huevos plates, but add a spine-tingling, eye-watering dish called huevos borrachos (drunken eggs), a grand mixture of sautéed onions, chiles verdes, and tomatoes mixed with scrambled eggs and cheese and served with refried beans and seven-inch-diameter flour tortillas. Jorge also has the best traditional hangover cure, menudo, which washes down nicely with a Tecate.

When Matt Martinez first opened El Rancho in 1952 he would run outside and give free meal tickets to pedestrians waiting for the light to change at the corner of East First and Trinity. It was his third restaurant try, and he is no longer handing out meal tickets to get customers. “Monroe Lopez [of El Matamoros] is the first man in Austin to make a million dollars in Mexican food and I am the second,” claims Martinez.

Matt is probably most renowned for his Mexican seafood. Redfish veracruzana is especially good these days, and the seafood enchiladas and barbecued shrimp a la Matt Martinez helped put El Rancho on the map. His Mexican pizzas are fair examples of this ethnic crossover, and the one with beans is Darrell Royal’s favorite dish. El Rancho’s Tex-Mex currently suffers from lackluster sauce and unmemorable guacamole, but it comes in almost endless combinations, and his chile relleno stuffed with pecans and raisins and topped with sour cream, is a must for many customers. Some old-time El Rancho regulars, if prodded, would confess El Rancho isn’t up to its old standards, but these loyalists continue to return out of a sense of tradition.

Austin’s first Mexican food millionaire, Monroe Lopez, has several other firsts to his credit: the crispy taco, air conditioning, tap beer, frosted beer mugs, takeout and delivery service, and an all-you-can-eat Tex-Mex dinner, which has kept countless UT students from starvation. Lopez has only the 325-seat El Matamoros these days, but at one time he owned four Austin restaurants. “I had eight hundred seats and I figured I could fill them up twice a day at $1.25 a meal for $500-a-day food costs. That was in 1966, and I made at least $2000 every day. The meal was rice, beans, enchiladas, and tacos. That’s how the all-you-can-eat idea got started.” Lopez’ Tex-Mex is pedestrian at best, his tortillas are fresh made, and his crispy tacos are still the best in Texas.

If you are pining for the regional foods of interior Mexico, and you can’t catch a flight to Mexico City, Austin’s San Miguel should appease you. After eating there, you might investigate Diana Kennedy’s Cuisines of Mexico to get an idea of the time and ingredients that go into their dishes. Ms. Kennedy served as a consultant when San Miguel opened in 1975, and the cooks have followed her culinary suggestions without deviation.

San Miguel’s beginnings have been precarious, which isn’t surprising considering that the vast bulk of Texans’ Mexican food allowance goes for Combination Plate Number One. But consider a few of San Miguel’s alternatives: splendid Cornish game hen en mole poblano or Tikin Xik, a filet of fish broiled Yucatan style (both cheaper than carne asada or shrimp a la Matt Martinez at El Rancho). A new menu is on the way that will emphasize Ms. Kennedy’s Norteño-style dishes. Besides the excellent food, there are San Miguel’s spacious, high-ceilinged rooms, alfresco dining, a snug bar, and strolling mariachis, all of which have caused some wistful diners to think they were in fact dining in México, D. F.

FORT WORTH

Cowtown is devoted to standard Tex-Mex offerings. No restaurant we visited from the legendary Joe T. Garcia’s to Betty Mendez’ superior takeout garage deviated from standard entrees, except Caro’s on Curzon. By request only, a whole cabrito over coals is yours for $60, or the famous Caro’s roast suckling pig for $150 is carved for twelve at table, apple in mouth included. This Tex-Mex domination is totally in character in the most Texan of Texas’ cities, but the variety of dishes that are available in other large urban areas is sorely missed.

Founded in 1928, The Original is Fort Worth’s oldest Mexican food restaurant. It serves good Tex-Mex dishes to the wealthier westside Cowtowners who aren’t taking a visiting New Yorker to Joe T. Garcia’s for adventure. It is owned and operated by a freight train conductor, Joe Holton (he rides the Frisco twice a week), and the most popular dish is the Roosevelt Special (named for Elliott, not Franklin or Grier, who lived in Fort Worth after he was first married).

An expansion last year hasn’t hurt the reliability of the food and it keeps people from winding around the block in waiting lines. Like a good pair of Levi’s, The Original is plain, dependable, wears well, and you develop an attachment for it.

The most famous out-of-the-way, bad-part-of-town restaurant in Texas is Joe T. Garcia’s Mexican Dishes, which is what this spot has served family style for forty years. The Garcias have carefully preserved an exterior image that coincides with the unpaved streets and tilting old building. But walk in and behind the funk you’ll find flamboyance like a Hollywood movie set: new dining rooms, bar, patio, swimming pool, and a stage—just the place for Fort Worth’s debs.

There are other things that belie the shanty-funk appearance. No longer do you have to walk through the kitchen. No longer do you fetch your beer from the refrigerator; waiters bring it to you, unheard of in the days gone by. The old pit is still there, where the late Mr. Garcia fixed barbecue (the restaurant’s first product, along with tamales). The food remains good but not great.

What a surprise to find that the three excellent Fort Worth-area Caro’s are direct descendants of the famous Caro’s in Rio Grande City, one of the border’s best. Sandra Vivion, wife of the Curzon Caro owner, Robert, grew up in the Caro family and brought her family’s expertise north. If there was justice, cheers would still be ringing in her ears from grateful Cowtowners.

My tour of the kitchen revealed an authentic molina on which corn is ground for Caro’s best offering: puffed tostados. One of the most economical deals in Tex-Mex food is an order of six puffed tostados filled with either guacamole, beef, or chicken. These huge numbers cost you $1.

Robert picks his ingredients wisely, choosing California Calavo avocados over the too-sweet Florida variety, and insisting his refried beans are prepared in pure lard. While I was in the kitchen I saw the cooks boiling chiles anchos and grinding comino seeds to make fresh gravy for enchiladas. The roast suckling pig spectacle is no joke; the place serves on average one a month. And Glen Rose farmer-writer John Graves has in the past supplied Caro’s an occasional kid for cabrito.

A year ago I noticed a yard sign, Mendez’ Mexican Food, in southside Fort Worth, but I foolishly passed it by. Not this time. Let the others have fun at Joe T. Garcia’s; here is where Texas-Mexican food is prepared the right way. Betty Mendez, retired two years ago from the drapery department of Stripling’s, converted her husband’s garage into the finest takeout Mexican food spot in Texas. Everything is done by hand, either hers or her daughter-in-law’s, including grinding corn to make masa for tortillas. Flour tortillas are unequaled, the dough mixed and rolled while you watch. Instead of ground meat, they use beef and pork roast from the Courthouse Market. And, as in millions of Mexican homes several hundred miles south of Fort Worth, every thing is cooked in pure lard. Two tacos, which will fill you up for six hours at least, cost 80 cents; a dozen perfect flour tortillas go for 70 cents. I swoon from time to time thinking about it.

EL PASO

Remember that El Paso is practically New Mexico, as close to Los Angeles as to Houston, and that things are different. New Mexico, much more than Juarez or Texas, dictates the Mexican food styles. The enchilada choice in El Paso is not between beef or cheese but between flat or rolled, red or green, with or without an egg. Chile sauces—red and green—play a large role in the cuisine and on the menus in almost all restaurants. Enchiladas, burritos, chilaquiles, and chili con carne are often designated red or green. New Mexico is outranked only by California in chile production, and one of the richest growing areas is the Mesilla Valley, thirty miles north of El Paso.

Casa Jurado near UT-El Paso is our favorite. Señora Estila Jurado began catering her famous miniature tamales to her friends from her home and, as often happens, received enough praise to try other things. Her tamales remain the house specialty, but we like the enchiladas norteñas, flat, stacked enchiladas with lettuce and asadero mixed between the tortillas. The quesadillas, also with asadero, are exceptional as are the enchiladas poblanas with mole and cheese.

La Hacienda is El Paso’s oldest (est. 1940) and most architecturally representative restaurant, with high ceilings, verandas, porches, and hacienda-like adjoining rooms. It used to be part of old Fort Bliss and dates back past the turn of the century. Nowhere is Mexican food cheaper—top price is $2 for the Mexican plate with a chile relleno. Although the La Hacienda Special, a flavorful beef caldillo, is generously meaty, other entrees can be disappointing. No matter. To get a feel for El Paso this is the place.

The most interesting and authentic Mexican menu (all in Spanish) we found was at Moe’s near Ascarate Park. All the offerings are excellent and unusual, like lengua en mole (tongue in mole, served with beans).

Whenever in an unfamiliar city, search out a good neighborhood bar, and if it has a restaurant, so much the better. It’s a rule I never break, and Tony’s is proof it works. Also it’s near the Chamizal area, which is the fastest entrance to Juarez, where more and better Mexican food awaits. Tony’s and Studs Terkel would get along. A little chatter, fights on the TV, and lots of good food. Tony’s unique caldillo (chile verde sauce this time) isn’t as good as La Hacienda’s, but the chiles rellenos are fine, crisp, and flavorful.

- More About:

- Tex-Mex

- Mexican Food

- Longreads

- Chili

Flat is Beautiful

Flat is Beautiful

The Mexican Can-Can

The Mexican Can-Can Behold the Bean

Behold the Bean