This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The wine scene in Texas is a Jekyll and Hyde affair. The refined, sedate, and well-mannered side of the personality turns up in settings like the recent wine tasting held in the cool, oak-raftered vaults tucked away beneath Tony’s posh Houston restaurant. Present are some twenty oenophiles, including such notables as Bordeaux vineyard owner Alain Querre; Henry Kucharzyk, a consultant with Richard’s wine stores in Houston; and a young lawyer who has amassed what may be one of the country’s finest private cellars at his home in River Oaks. Across the candlelit table, with banks of orchids and mums, strawberries and artichokes, Monsieur Querre rolls a 1961 Chateau Ausone appreciatively over his tongue. He pauses. “You Texans must have seventy per cent of the great wines in the world, of the old bottles that have disappeared from France. My impression of these vintages,” he says, “is absolutely fabulous.”

The Mr. Hyde half of the personality makes itself known by the sheer weight of statistics: labels like Lancers rosé, Gallo Hearty Burgundy, Yago sangria, and Blue Nun liebfraumilch account for up to 90 per cent of the wine sold in Texas, according to some reckonings. Part of the problem behind this preference for the mundane has been that wine—like art, literature, and music—requires leisure to be appreciated. We Texans have been so busy drilling oil wells, punching cows, and helping put a man on the moon that we’ve hardly taken a minute to enjoy some of the finer things of life. Now, though, with our position in industry and high finance presumably established, we are relaxing enough to taste the fruits of our labors. Wine—fine vintages, good bottles, cheap jugs—is being bought up in ever increasing quantities as Texans try to make up for lost time by diligent consumption.

Texas ranks as the eighth-highest state in the U.S. for wine sales, which have been growing at about twice the national average, according to some calculations. Wine is edging up on beer and mixed drinks as the beverage of choice at restaurants and private gatherings. This is especially true among people under 35, whose reasons for drinking wine are disarmingly broad. Among other things, wine is thought to be less fattening than beer and more healthful than hard liquor. One Austin retailer reported a customer renouncing beer in favor of wine and tennis, and a young Houston executive declares it is good for the digestion. Besides, she adds, “it’s cosmopolitan.”

Cosmopolitan it may be, but the taste of most Texans who drink it isn’t—at least not yet. Most of us prefer something a little sweet, although we would never admit it. Only a dry wine is thought to have real class. “If a customer thinks liebfraumilch is dry, I don’t tell him otherwise,” says one merchant. “I’ll call it ‘soft’ maybe, or ‘feminine,’ but never ‘sweet.’ ” Wine is rather like coffee, he adds. “You prefer the first cup of coffee you ever drink to have a lot of cream and sugar.” He adds that he expects the statewide palate to mature—eventually.

And well it may. Although for the moment the brothers Gallo and their cohorts account for the majority of sales, the small remainder of purchases is at the top of the sophistication scale, a hopeful sign. Centennial Liquor Stores, a 23-branch Dallas chain, is one of the largest wine importers in the country, which suggests that a coterie of connoisseurs there is prepared to spend freely on good imports. Many in the wine trade in Houston say their city will soon catch up with such traditional markets for fine imports as New York, Los Angeles, and Washington.

Houston and Dallas aren’t the only centers of budding connoisseurship. Other major cities, particularly Austin, have their share of wine imbibers. There are enough oenophiles in the state to have formed six chapters of Les Amis du Vin and one (in Fort Worth) of Confrérie St. Étienne d’Alsace. Even in the hinterlands, the word is out that wine is something to reckon with. Nowhere, in fact, is the schizoid nature of Texas wine appreciation (or lack of it) more strikingly revealed than in the twin cities of the western oil patch, Midland-Odessa. This is the headquarters for “West Texas No. 1 Wine Merchant,” as the package store chain with the improbable name of Pinkie’s announces itself in red lights on a highway billboard. As at most liquor outfits in the state, Pinkie’s wine sales are booming—up maybe 300 per cent in the past ten years. The stores—21 of them altogether—dot towns as small as Post (population 4010) or as large as Lubbock, but the flagship of them all is in Midland. Located in a mall near the manicured suburbia around the Racquet Club, the Midland Pinkie’s comes as quite a surprise to anyone who expects shelves lined with jug wines. One Houston connoisseur who visited it was amazed to find, in a hushed, shag-carpeted section of the store, such vintages as 1952 burgundies and 1937 sauternes and a 1935 Simi Sonoma Zinfandel.

Don McCown, the spare-framed wine sales manager for the group, says the selection isn’t just for show; his customers buy, and buy, and buy. They’ve cleaned him out of Dom Pérignon for the moment, and he has had to order fifteen cases of Lafite-Rothschild for an oilman. Another customer, an interior decorator, “bought a hundred cases of German wine for her new home.” In fancy neighborhoods in Midland, the joke is that anyone who’s anyone has an empty magnum in the garbage—every week.

Odessa is a different story. The epitome of Texas drinkers can be found at the Pinkie’s here: an unshaven man in a “Let’s Boogie” T-shirt hugging a half gallon of whiskey to his beer gut, and his wife, with penciled eyebrows and hair curlers, pricing the Popov and bourbon. Another customer is deciding whether to splurge $1.49 for a domestic rosé. In Odessa, as throughout Texas, low-priced domestic wine, especially jug wine, moves fast. So do innocuous, inexpensive imports, like the 1975 Schloss Kobold liebfraumilch, which Pinkie’s has displayed in a large green tub just below the Original Texas Half-Pint Smirnoff and the rows of Clorets. The liebfraumilch is specially featured at $2.69 a magnum and the stores in the chain will sell perhaps a hundred cases among them in two weeks. This will be encouraged by some pretty unsubtle hard-sell techniques: the liebfraumilch will flash on thousands of West Texas TV screens as the Wine of the Week.

The quality of advice about wine that one is likely to get in a Texas wine store reveals pretty much the same split-screen picture as the general habits of consumption. On the one hand there is Henry Kucharzyk, with Richard’s in Houston, who looks every inch the elegant connoisseur and is, in fact, just that. His knowledge of grapes and growers and vintages is as complete as you’re likely to find, in Texas or out. On the other hand there is the fast-talking 24-year-old salesman at one of the Pinkie’s stores, who sounds extremely erudite on the subject of “this big David Bruce Chardonnay” he is storing at home until he happens to let slip that “I get a lot of my information from the labels on the backs of the bottles.”

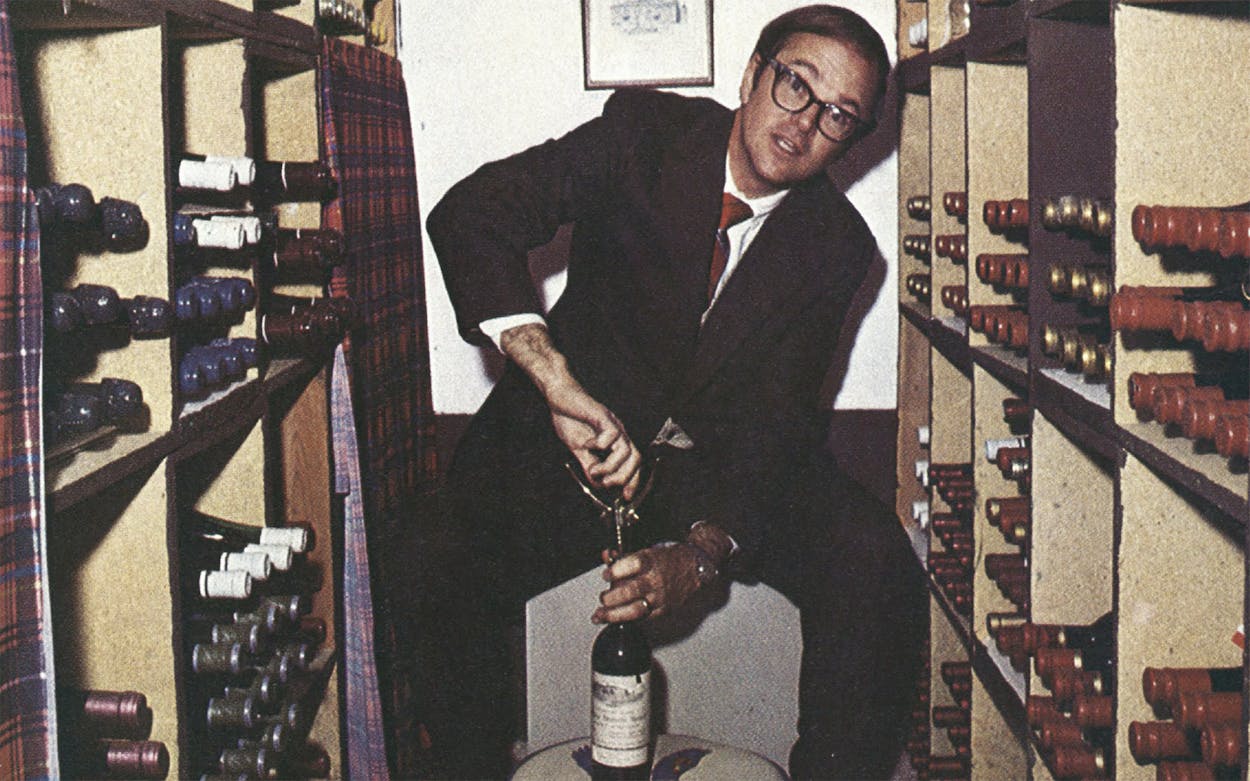

Outside the wine trade, Texas cognoscenti tend to be very private people—and more than a little iconoclastic. The 35-year-old River Oaks lawyer who was at the tasting at Tony’s, and whose collection is one of the finest in the country—possibly the world—declines to have his name used, his cellar is so valuable. Actually, it is a converted garage, not a cellar, although it does have a brick floor. He admits that gravel would control Houston’s notorious humidity better, but brick is preferable for maintaining the temperature at the classic 53 to 55 degrees in case his air-conditioning unit goes out. In the room, a staggering 5000 bottles are crowded into plywood racks and tagged with ceramic labels, a practice copied from the French. The range of vintages is impressive: he has drunk the 1887 Margaux that came from Scotland’s Glamis Castle; he has yet to decant the 1947 Cheval-Blanc. Recalling the 1867 Chateau Montrose, he pauses: “Let me think. Was it from the Earl of Rosebery’s or the Gladstone family’s cellars?”

Among those collectors who don’t shun the spotlight are San Antonio investment banker Hobby Abshier and his wife Nancy. Going against the practice of many of their colleagues, the Abshiers scorn the squirreling away of Victorian vintages. “That’s foolish. Wines peak out,” Abshier says. Instead, he favors relatively young Bordeaux (no older than twelve years), which he packs into the styrofoam-insulated Hill Country room that serves as a cellar.

James DeGeorge of Houston also prefers to buy more recent vintages. He has about 1200 bottles in a large tile-floored, refrigerated room that he uses as a cellar. The real estate developer, who acted as a consultant for several Houston restaurants, drawing up their initial wine lists, does not have an overly reverential attitude about his hobby. “Wine is fun,” he says.

The burr haircut and primrose-colored jumpsuit of wine collector Jim Albright, a fifty-year-old Austin psychiatrist, suggest a certain eccentricity, and sure enough, his 1000 bottles are lodged at his home in a separately air-conditioned basement room which, with its deep red walls and silver candelabra, looks like nothing so much as a set from Rosemary’s Baby.

The antithesis of this is the prefab “wine vault” that 32-year-old Howard Rachofsky has installed in a bedroom of his ultramodern Dallas duplex. Looking like a sauna bath, though at 58 degrees it feels a lot chillier, the $2850 vault stores about 850 bottles. The curly-haired Rachofsky, by profession a stock trader, says he gets pleasure out of buying as well as drinking. “I don’t play the wine market like I play the stock market, though,” he adds, “because I don’t sell my wines.”

Not all Texas oenophiles have separate cellars; some simply keep their cherished bottles around the house. These aficionados split into two camps—those who pamper their wine by turning up the air conditioning and those who don’t. Bill English, a robust Austin restaurateur, falls into the first category. He sleeps under blankets year-round because “I share the bedroom with part of my personal wine collection.”

Those who fall into the second category exhibit a typical Texan trait: a profound distrust for the conventional etiquette. One female Houston collector keeps her apartment at a comfortable 72 degrees and says her wines will just have to live with it. Gary Macklin, another Houston connoisseur and the editor of a magazine called Refrigerated Transporter, is aware that French vaults maintain 55 degrees through natural earth temperature and dampness but, rebelliously, he doesn’t agree that 55 is essential. “My house stays about 70, and the bottles are in the living room. It’s one of those old wives’ tales to insist on 55. What wine does need, though, is a constant temperature.”

The Texas climate poses problems not just for the private oenophile but the wine wholesaler, the retailer, and the club or restaurant owner as well. Lacking the facilities, not to mention the inclination, for properly handling large quantities of wine, some wholesalers stack costly and delicate imports in tin-roofed, un-air-conditioned sheds designed for hard liquor, a sturdier commodity. If the wine begins to go “off” or cooks completely to vinegar in the summer, and some inevitably does, they unload it at drastically reduced prices in what some angry retailers call a Texas Bake Sale. Other retailers, and some restaurants, see the bake sales as an ace in the hole. They snap up the stuff, then proceed to sell it at a discount or pawn it off as the house wine. After all, they rationalize, it’s not them but the public who may get gypped.

Ordering wine in a restaurant can thus become an occasionally tricky proposition, and not just because some of the bottles have gone bad. Unless he wants to burn out his checkbook, a novice who is selecting a wine should keep several things in mind. First it is advisable to size up the decor; the more expensive the place looks, the bigger (normally) the markup. One hundred per cent is the bare minimum to expect. Max Porch, a goateed salesman for accent Wine & Spirits in Houston, says, “I suggest they [the restaurant owners] double their money plus five per cent on a bottle. But that’s within a minimum and a maximum. You wouldn’t want a $4.50 price on the list in a restaurant with thick carpets and chandeliers. And in a nice place, you’d want to have a maximum over $25.” With markups tending to exceed 300 per cent in most places any more plush than a greasy spoon, the house wine often seems the logical alternative. But if this didn’t originate in a bake sale, it is probably a jug wine from California—at a cost of 3 to 7 cents a glass to the restaurant and $.75 to $ 1.25 to you.

Another potential snake pit is the verbal wine list. In some fancy restaurants, the printed list mentions a mere fraction of the bottles on hand, the rest being available upon request. Of course, this does not always signal that something funny is going on. Tony’s, in Houston, lists 66 “more popular” varieties, which owner Tony Vallone finds adequate for the majority of his customers. Patrons who want something rarer are invited to walk downstairs to the cellar and browse among more than 160 other labels, which are in boldly priced bins. About the only snag a customer will hit is Tony’s possessiveness. He refused to take $950 for one old Lafite he particularly treasures and he has hiked the price of a 1929 jeroboam of Mouton-Rothschild to an amazing $9500.

The occasions you have to beware are when you’re dining at restaurants which, instead of giving you a list to size up, size you up. Some say they do this for the noblest of motives. Austin restaurateur Bill English, proprietor of English’s, claims that wine lists bristling with complicated and obscure foreign names confuse the average Texan. “So I keep my wine list in my head. I size up what you want and what you want to spend and generally, if you don’t appear knowledgeable, I’ll recommend something medium-priced and not too dry,” he explains. “A really dry wine might put you off. You might think it was vinegary.” English adds that he doesn’t play games with his customers. Some of the 200 labels he carries are marked up as little as 50 per cent and he says he keeps a master price list for the sake of “consistency.”

Unfortunately, consistency isn’t always the case with restaurants using a verbal list. At Maxim’s, which claims the Southwest’s largest cellar, only 32 wines are named on the printed list; the other illustrious labels, some 400 of them, are stored in a murkily lit, warmish room opening straight off the parking lot in the adjacent Foley’s garage. If the bottles in the cellar bins have marked prices, it certainly isn’t obvious, which may be why three parties of customers have recently been quoted three different prices for the same Cotes du Rhone: “$10.50,” “about $12.50,“ and “about $14.50.” Ronnie Bermann, the 32-year-old owner’s son who gave each estimate, says, “A lot of places have a long list, but we’d rather explain and recommend our wines. We have a set price. Well, not a set price, but basically a set price.”

Strangely enough, it is not illegal for a restaurant to vary its verbal pricing according to its customers, although printed pricing must be consistent. This is one reason that wine buffs are less than happy with the Texas Liquor Control Act (LCA)—a 180-page (not counting the inserts) tangle of dicta that were obviously written with hard liquor and beer, not wine, in mind. Among the less endearing rules in the act is one that prevents a customer from taking his own bottle of wine into a restaurant that has a mixed-drink permit (which means, in effect, any large restaurant). Thanks to this rule, you have to pay $10 or $12 for a moderate wine that you could have picked up for $4 at a local package store on the way out to eat—assuming, of course, that the restaurant even has in stock the wine you wish to order. “You wouldn’t take your own steak in,” a Texas Restaurant Association representative said defensively when questioned about this practice. On the positive side, the LCA does allow any wine left in a bottle bought with a meal to be doggy-bagged home. Before this was permitted, the wine had to be either drunk or left. “Some people in Houston were extremely upset to be told they couldn’t take their wine out,” recalls the TRA spokesman. “One customer emptied the rest of his bottle on the table.”

What lies ahead for wine aficionados in Texas? Even allowing that the average Texan may drink more wine and know more about it than, say, the average Idahoan, we’ve got a long way to go. You have only to eavesdrop in Texas restaurants to hear such comments as “We’ll have a dry wine—a sauterne” or “We’ll have a Schloss.” Hopefully, though, it’s only once in a lifetime that you’ll have the luck (as I did) to see a customer, intent on impressing his friends with his knowledge of tasting rituals, take the cork that was offered to smell and feel—and pop it into his mouth.

Hope for improvement any time before the next century might logically be expected to come via those most American of enterprises—advertising and marketing. Consider this: Ray Hankamer, a savvy Houston businessman, has teamed up with a San Antonio fruit juice exporter to bring in inexpensive wine from Europe and deliver it in twelve-bottle cases directly to Texans’ front doors. “I saw what six packs did for beer sales and I expect twelve packs to do the same for wine,” he says in all seriousness. “I know what Texans’ wine tastes are.” Perhaps he does. Perhaps he’s hit on the magic key that will bring the joys of the grape to the masses. As one Odessa beer drinker said about wine, “I’d like it real good in cans.”

Sharon Churcher has written for the Wall Street Journal and Maclean’s, a Canadian national news magazine.

- More About:

- Libations

- Wine

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston