This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Well, looky here now. Ol’ Bill Clinton, the pride of Hope, Arkansas—Watermelon Capital of the World—done got himself elected president of the entire United States, including Texas. On top of that, the boy beat not one but two Texans in the process. Both major kinds of Texas Republican, in fact: your white wine and Brie, Daddy’s money, carpetbag, and art museum type, and your more authentic know-it-all temperamental tycoon bidnessman variety. One who pronounced the word “Arkansas” like it was a rodent nibbling his pork rinds; the other who announced during the presidential debates that the place was “insignificant.” Or was it “irrelevant”?

Don’t guess it matters much anymore, does it? Chances are we’ve seen the last of both of those men on the national political scene. But gloating aside—and there’s not an Arkansan worth his hog hat who isn’t gloating, including the ones who loathe Bill Clinton—the truth is that most of us feel a genuine sense of redemption. Even as an adoptive Arkansan who married the place 25 years ago and who has spent enough time living and working in Texas to qualify as an expert witness, I found it real hard not to take the campaign rhetoric personally. Local patriotism runs very strong here, and it tends to be highly contagious.

Every bit as much as Texas does, you see, Arkansas comprises a world unto itself—“Not quite a nation within a nation, but the next thing to it,” as journalist W. J. Cash wrote of the entire South of 52 years ago. Indeed, schoolchildren here have been taught for decades the myth that Arkansas alone among the states has the natural resources—water, timber, oil, natural gas, and vast stretches of fertile alluvial soil—to build a wall around itself and nevertheless thrive. Also like Texans, we’ve often been tempted to give it a try.

Before Clinton’s candidacy, however, Arkansas rarely attracted Texas-size attention in the national press unless something appalling or embarrassing had happened: floods, tornadoes, mass murders, or preposterous legislation, such as the 1981 Creation Science Law, which mandated the inclusion of biblical fundamentalism in class discussions of evolution. Yankees who couldn’t locate the Ozark Mountains on a map to save their lives knew all about the Little Rock Central High integration crisis of 1957—and therefore all they needed to know about Arkansas.

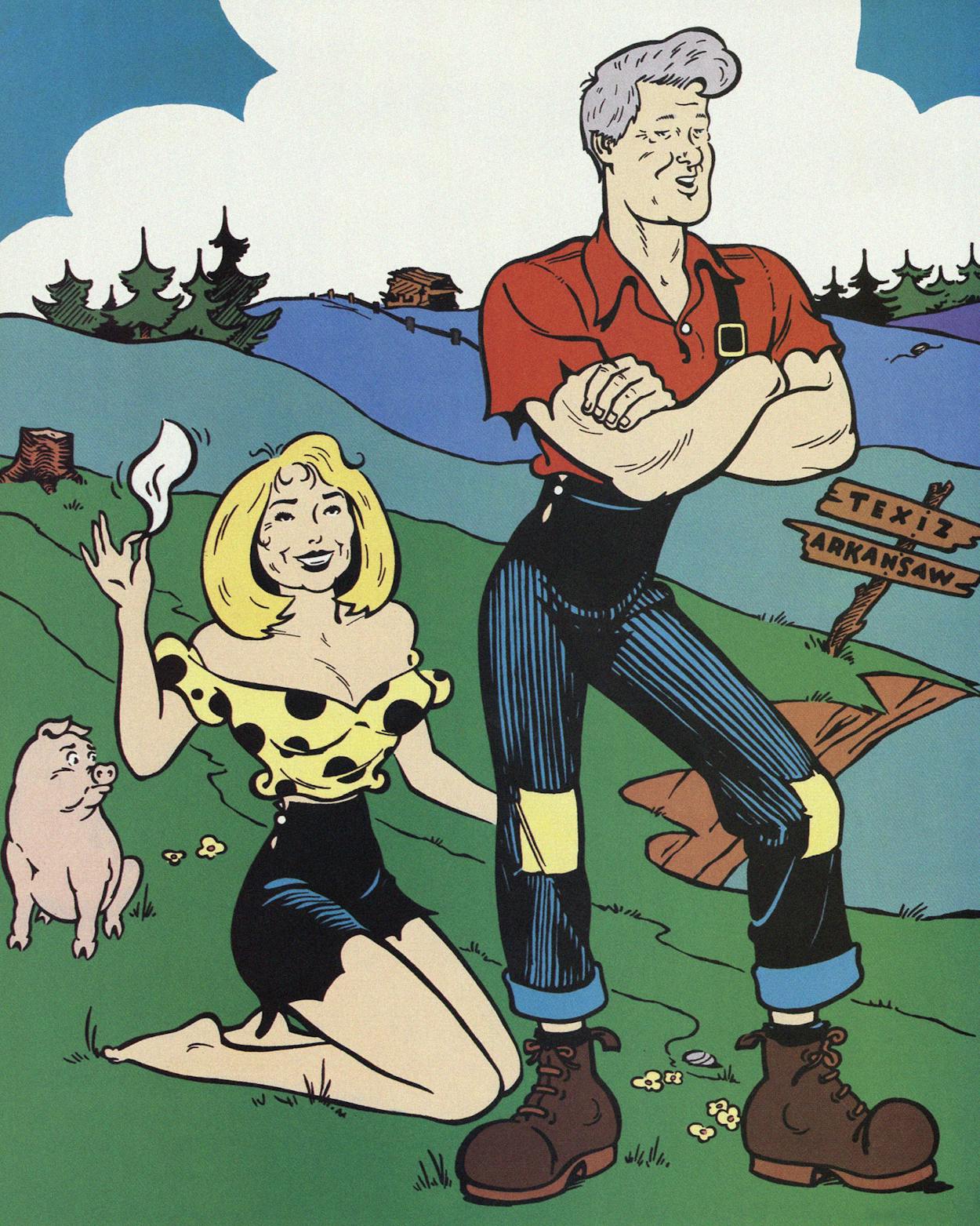

Actually, this tradition of mockery and scorn dates all the way back to territorial days. A book of hillbilly jokes called On a Slow Train Through Arkansaw was a huge best-seller around the turn of the century. Mark Twain mercilessly satirized the state’s backwoods squalor in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Al Capp’s yokel comic strip character Li’l Abner was understood to live in Arkansas. (In fact, there is still a Dogpatch theme park in the town of Harrison.) When Lou Holtz was the head football coach at the University of Arkansas, he told Johnny Carson on the Tonight show that Fayetteville wasn’t the end of the earth, but you could see it from there.

Even today, well-meaning commentators can’t help but pile on. Back during the primaries, for example, Time’s Margaret Carlson identified the perennial boy wonder of Arkansas politics as the Doogie Howser of his hometown and one of the first from the area to go to college. Had Time never heard of the Fulbright fellowships? Senator J. William Fulbright was a Rhodes scholar and president of the University of Arkansas (not to mention a Razorback football hero) before Clinton was born. While Clinton was wowing them in grammar school, Fulbright was standing up to Joe McCarthy’s red-baiting on the Senate floor. By the time Clinton sought his advice on the draft in 1968, Fulbright was the chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, fighting Lyndon Baines Johnson over Vietnam.

Probably the best way for you Texans to understand how we Arkansans feel about this stuff is to recall how you reacted when LBJ was mistreated by segments of the press and the eastern establishment after he ascended to the presidency in 1963. For those of you too young to remember, it was similar to the way Texas sportswriters greeted the news that a rube from Little Rock had bought the Dallas Cowboys.

The assumption, at least for now, is that Clinton’s win has changed everything. Thanks to him, we’re suddenly respectable. How much credit the president-elect has taken for this—as Prince Hal to our Falstaff—is hard to say. Quite a lot, one suspects; that’s pretty much the way most fervid local supporters have always seen him. On the other hand, Clinton’s credentials as a local patriot have rarely been questioned. Witness the now-famous story of how Hillary first met him in the Yale law library bragging on those Hope watermelons. He could, after all, have begun his lifelong quest for the presidency as George Bush did—by moving to a state with more electoral votes—but he came back home instead. On election night the euphoric throng in downtown Little Rock was celebrating a whole lot more than a Democratic victory. The feeling was almost palpable: At last we belong.

Paradoxical Politics

If you’re wondering what kind of president Bill Clinton may turn out to be, the Arkansas political tradition offers much to ponder. The state’s political history is a rich parade of demagogues, buffoons, and statesmen. As the example of Fulbright shows, Arkansas has long been a bit of a paradox, electing strong iconoclastic leaders often seemingly at odds with the state’s backward image. Congressman Wilbur Mills was another such case. Though Mills’s ignominious plunge into the Washington, D.C., tidal basin with a stripper tended to obscure his accomplishments, he was, for much of his career, Congress’ acknowledged expert on fiscal policy and taxation.

In statewide elections, for a whole bunch of historical reasons that Republicans have been slow to grasp, Arkansas remains essentially a one-party state of yellow-dog Democrats, almost a museum exhibit of the Solid South of yore. Bruising Democratic primaries tend to occur only when there’s no incumbent in a major constitutional office. Bill Clinton’s last well-financed primary challenge, for instance, came in 1982, after his anomalous defeat by Republican businessman Frank White. Partly due to Clinton’s formidable political talent, he has faced token primary opposition ever since.

Undeniably conservative in the social sense, Arkansas also elects extremely liberal politicians. The Americans for Democratic action, a liberal lobbying group, gave Arkansas senators Dale Bumpers and David Pryor ratings of 90 percent last year.

Perhaps the best way to get a fix on Arkansas’ disjointed political history is to scrutinize the election results of 1968. That year the nation went stark raving mad, and Arkansas voters did their bit, awarding Independent candidate George Wallace their presidential vote, reelecting anti-war Democrat Fulbright to the Senate, and returning to office reform-minded governor Winthrop Rockefeller—Arkansas’ first Republican governor since Reconstruction. How strange was it? Rockefeller was precisely the sort of person you would have expected to lose: a divorced New York billionaire who drank heavily and opposed the death penalty.

Just beneath the surface, however, the results were more easily understood. Wallace’s 235,627 votes isolated the sorehead segregationist vote in the 35 to 40 percent range, where it remains to this day. Richard Nixon and Hubert Humphrey split 374,000 votes almost in half. Fulbright was, well, Fulbright, an internationally respected figure with whom many simply agreed to disagree. Rockefeller, meanwhile, completed the state’s liberation from the corrupt and aging machine of segregationist former governor Orval Faubus, helped by 105,000 black voters newly enfranchised by the repeal of state poll taxes in 1964. All three winners were perceived as their own men—independent voices in a place where politics tend to be extremely personal and where gritty underdogs are much admired.

Since 1968, no overtly racist candidate has come close to winning a statewide campaign. All successful gubernatorial candidates have stressed the same issues that Bill Clinton made his own: jobs and schools. Just as important, the suburban Republicans who make up the swing vote across much of the South have had relatively little impact here. Little Rock, you see, is the only Arkansas city big enough to have suburbs worthy of the name—and it has only about 300,000 citizens (counting North Little Rock and surrounding communities). Apart from a few Republican counties along the Oklahoma and Missouri borders, the GOP scarcely exists in rural Arkansas. In the 1990 primaries, 86,000 Republicans voted, compared with 491,000 Democrats.

Moreover, every Republican candidate for statewide office in recent years has made the same mistake George Bush made early in the 1992 presidential campaign. By allying themselves to the same Pat Robertson-style family values package that Bush embraced at the Republican convention in Houston, they’ve written off the state’s 15.9 percent black vote and run sectarian campaigns that alienate everybody but the true believers. Talking in code and mainly to each other, they are astonished and infuriated when the votes come in and a Dale Bumpers has once again beaten them like a yard dog.

Last year a Baptist preacher running for Bumpers’ Senate seat provided almost a textbook example of the phenomenon. Copying national Republican attack strategies, Mike Huckabee opened his campaign with a series of TV ads accusing Bumpers of voting to fund pornography four times. (Translation: Bumpers voted to fund the National Endowment for the Arts.) Hardly anybody believed the charge to begin with, and once Bumpers responded with apparently sincere anger, the contest was over.

The voters didn’t reject Huckabee’s accusation because they had been studying the Congressional Record. They simply felt they knew Bumpers better than that. In a small state full of country towns, the sheer intimacy of Arkansas politics is hard to overemphasize. Not everybody here knows everybody else, but it often feels as if they do. But even if they have only “shook and howdied” at campaign appearances, Arkansans tend to refer to politicians like Bumpers, Pryor, and Clinton by their first names. Their likes and dislikes tend to be personal rather than ideological and for that reason very hard to change. Knowing Dale or David or Bill as they do, they just don’t believe people on TV who paint them as anti-God, anti-family, and all the rest of it.

The point is that canny Arkansas Democrats who watched the GOP in Houston this year had to be astonished. George Bush was setting up to run exactly the same campaign against Clinton that his most recently vanquished Republican opponent, a former gas utility executive named Sheffield Nelson, had used to capture 42.49 percent of the vote in the 1990 gubernatorial election. If it didn’t play in Arkansas, how in the world did Bush and his advisers expect it to play in New Jersey and California?

Clinton’s Legacy

Predicting Clinton’s success based on his performance as Arkansas’ governor is a far trickier proposition. When it comes to character issues relevant to governing, Clinton has been difficult to fault. Never in his dozen years in office has there been a hint of financial wrongdoing—not even a questionable expense voucher. And if anything, Hillary Clinton’s law firm—one of Little Rock’s most prosperous corporate partnerships long before she came to town—has received a good deal less state business than it might otherwise have done without her.

As to Clinton’s personal morality: The man lives, breathes, eats, and sleeps politics. Anybody who agrees with Molly Ivins in not trusting politicians who haven’t got a weakness for whiskey and women ought to be extremely wary of the president-elect. Nobody has ever seen Bill Clinton drunk, and the reason behind his famous “I didn’t inhale” gaffe is simple: He probably didn’t. The boy has charm and personality to spare, but while others of his generation were running around barefoot, rolling joints, and listening to the Grateful Dead, Clinton was studying in the library and still into Elvis.

As governor, Clinton’s one all-but-universally admired action was his overhaul of the state education system, but it took a while for him to pull it off. After a first term spent aggravating powerful interests like the timber industry, he lost a 1980 reelection bid. The hot-button issues were the Carter Administration’s placing of thousands of Cuban immigrants at Fort Chaffee and Clinton’s increase of auto-licensing fees. But Clinton also caught flak for Hillary’s decision to keep her maiden name—a decision that contributed to his image as an overeducated pup who thought he was better than most Arkansans.

After wandering the state asking advice and forgiveness, Clinton returned to office in 1982, persuaded never again to offend a vested interest capable of making a large campaign contribution. He made education his issue and appointed Hillary the chair of a panel to revise accreditation standards for public schools. As significant as what the Clintons accomplished was the politically astute way they went about it. Hillary’s committee called for a carrot-and-stick approach: smaller classes in all grades and the introduction of classes in foreign languages, advanced math, and science in all districts. Many small rural districts had none.

Another feature of the Clinton program was accountability. All students would be regularly tested, and the results for each school district would be published. The committee also recommended higher teacher salaries. To justify the increase, Hillary recommended and Bill embraced a onetime teacher competency test to weed out manifest illiteracy—a bitter pill that won Clinton the enmity of the professional teachers organizations and cheers from everybody else.

To pay for his program, Clinton proposed a 1 cent increase in the state sales tax. With the slogan “No More Excuses,” the governor and his wife sold the package to a public willing, even in the midst of the Reagan Revolution, to tax themselves to pay for services they believed in. Even the insulted teachers weren’t permanently alienated: Clinton returned to the legislature in 1991 for another half-cent sales tax increase specifically targeted to teachers’ salaries. The long-term results have been clear if unspectacular. In the 1979–1980 school year, Arkansas teachers earned an average of $12,596, compared with $23,878 in 1990–1991. Test scores and high school graduation rates are up; remediation rates are down.

But even a masterful consensus builder like Clinton was unable to do very much about another issue: taxes. In his first term, the governor eliminated the sales tax on prescription medicines, but by and large, his efforts to reform the state’s arcane, inequitable tax structure have been stymied. A constitutional edict enacted in 1934 requires a three-fourths vote by both of Arkansas’ legislative houses to raise taxes other than the sales tax. Clinton tried to change that requirement, but his last effort, in 1988, failed by a wide margin. The result? Arkansans get next to nothing for the natural gas exported from the state each year while they still pay sales tax on groceries.

Cutting or eliminating taxes for businesses willing to relocate in Arkansas proved a far easier sell with the legislature, of course, as did the creation of an innovative state financing authority to issue tax-exempt bonds for the same purpose. The funding of a bond issue for a plastics manufacturer involved in a longterm labor dispute gave Clinton a chance to display ideological flexibility. He infuriated the state chapter of the AFL-CIO, but labor still voted for him for president. The alternative was George Bush.

Perhaps the most impressive characteristic of Clinton’s four and a half terms in office, however, was his political realism—his ability to work with Arkansas’ notoriously cranky one-party legislature. The clearest example of this came during the 1985 legislative session, when the Arkansas Highway Commission, composed mostly of Clinton’s own appointees, proposed a 4-cent-a-gallon gasoline tax for highway improvements. Tied to a quite specific list of projects, the plan could hardly have been made without the governor’s say-so. Sensing the public’s opposition, however, Clinton vetoed the bill and then allowed his supporters in the legislature to see to it that his veto was overridden, thus having it both ways on the tax issue while taking credit for the highways. No aloof hands-off leader, Clinton was around the Capitol constantly during the legislative session—wheedling, manipulating, horse-trading, and cajoling.

Sound familiar? It should: The politician whose name comes up most often when Arkansans speculate about what sort of president Bill Clinton might be is Lyndon Baines Johnson. There are differences, of course. Clinton is a nineties version of Johnson, more the Georgetown-, Yale-, and Oxford-educated smoothy than the larger-than-life Texan with his larger-than-life appetite for power. And Clinton is nowhere near as mean as LBJ—although some recipients of his angry late-night phone calls might disagree.

High Hopes

Ultimately, Bill Clinton’s success or failure will come down to his political character in the deepest sense. His most bitter detractors, right wing and left, assert that the president-elect has none, that he has no heart, no soul, and no conscience, that he is a perfectly functioning political reflex machine. Arkansas Republicans insist somewhat enigmatically that Clinton (a) has no principles of any kind but (b) is secretly a programmatic liberal who will bankrupt the country and ruin its moral fiber. Not surprisingly, Arkansas’ tiny Austin-style anti-gravity left has come to an equal and opposite conclusion: He is a programmatic conservative with no principles. All the same, the majority of Arkansans believe that Bill Clinton is simply the most gifted politician this state has ever produced, at a time when—conventional wisdom to the contrary—the nation has never needed a politician so badly.

But even Clinton’s most passionate admirers confess to a feeling of unreality about the whole thing. Our shiny new reputation is tied to his, yet the vastly impersonal nature of the presidency makes us wonder whether the Arkansas experience is transferable. Next to our down-home, lovable, crazy little old state, the world of the White House—and of Boris Yeltsin, John Major, and nuclear weapons codes, not to mention all those billions of strangers to whom the president of the United States is an abstract symbol to be hated or revered—seems remote and beyond comprehension. For those of us accustomed to running into Bill or Hillary at social events, movie theaters, or ball games and chatting about politics, detective novels, the Razorbacks, or what have you, it’s like one of those stories in classical literature in which Zeus seizes some ordinary mortal by the neck, flings him into the sky, and turns him into a constellation.

Sure, compared with some of the scoundrels and nonentities who have occupied the Oval Office in our lifetime, Bill Clinton certainly seems up to the job. Still, for his sake—and ours—we’re praying that he is. Real hard.

Gene Lyons, a former associate editor of Texas Monthly, lives in Little Rock.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Bill Clinton