This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Vultures rode silent currents of wind, oblivious to the pickup that humped and rattled across the Circle C Ranch. The truck crossed the dry bed of Slaughter Creek and passed through a gate into a pasture where more than a hundred head of garden-variety cattle grazed beside a pond. Ira Yates, who owned the ranch and whose partner was developer Gary Bradley, was now directly over the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone. “How many nitrates do you think’s in all that cow shit?” Yates asked. “There have been cows here for a hundred years, right over the aquifer recharge.” Nitrates were among the pollutants with which Gary Bradley was said to be plotting the demise of Austin’s quality of life.

That scrubland pasture didn’t look like a battle zone, but it was. Late in 1983 a nasty and complex exercise in power politics erupted in Austin, and that pasture, along with the rest of the 4600 acres that made up the Circle C, was its epicenter. Gary Bradley wanted to develop the land into residential property. He and his partners stood to make as much as $50 million, and they did not want the project stopped.

But the Circle C was one of a cluster of old-time ranches that stretched nearly 100,000 acres south of the city, blanketing the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone. Environmentalists were worried that the aquifer was being polluted, which in turn would pollute Barton Springs, the pristine natural pool in the center of Austin. Austin’s voracious land boom was threatening to gobble the goose that laid the golden egg, for there was really nothing that distinguished Austin from most other cities except the natural beauty of the springs and its setting at the edge of the Hill Country. Local politicians were caught between pressure for growth and the need to protect the resources that had brought developers to Austin in the first place.

Yates and Bradley knew that before they could get the city of Austin to approve their development—a time-consuming and tricky task in itself—they would have to weather an attack from environmentalists. What they didn’t know was that they had a quieter, more powerful enemy. Austin had entered the age of big land deals, big problems, big money. Gary Bradley’s opponents in this new game were not just environmentalists and politicians but other developers. The development of the Circle C property might slow down growth north of town, where at least two of Bradley’s biggest competitors, Bill Milburn and the Nash Phillips–Copus Company (NPC), had major holdings. Bradley was in for a tough fight.

The region of the aquifer that had the environmentalists up in arms, the region that recharged Barton Springs, started near the town of Kyle, about fourteen miles south of the pasture where Yates was standing, and ended about seven miles north of it, at the edge of the Colorado River as it entered downtown Austin. Barton Springs was just south of the river and a little upstream from the city’s central business district. The Edwards Aquifer itself covered a much larger area. Curving gently from south to north, it ran from about Brackettville through Uvalde, San Antonio, Austin, and as far north as Temple. It poured 32 million gallons a day into Barton Springs, and a small percentage of it ended up in Austin’s drinking water. Small as aquifers go, the Edwards was also exceptionally fragile because of the limestone terrain: there was hardly any topsoil to filter runoff water before it returned through cracks and crevices to the aquifer. The water was sweeter and purer than that of most aquifers, and it supported a variety of exotic aquatic life, including the Texas blind salamander and the toothless catfish.

The aquifer was of enormous symbolic importance because it fed Barton Springs, Austin’s most cherished landmark. If a city could be said to have a soul, Barton Springs was Austin’s. Citizens who had not submerged themselves in its bracing waters for years remembered the experience as clearly as they remembered their first love affair. Barton’s was a symbol of what Austinites liked to call “quality of life.”

If you attended the University of Texas in the last ten years or so, as did Gary Bradley and almost all of the new breed of developers who have made millions from Austin’s land boom, you know about that old dream called quality of life. You wouldn’t recognize the place now, but back then Austin was a sleepy college town with a bohemian style and an economy disproportionately dependent on the university, the Capitol, and the number of royalty checks in the mail. Lured by green hills and spring-fed waterways, artists, writers, musicians, and assorted freethinkers settled here among the transient politicians and academics. In that old dream, at least, Austin was an idyllic chain of tumbledown mansions, porch swings, and tomorrow-is-soon-enough attitudes. Everyone seemed to have plenty of time to revive himself in the icy, clear waters of Barton Springs, or to picnic under the giant elms and pecans on the Capitol grounds, or to drink beer at Scholz Garten. The beloved Capitol building was man-made and could be replaced, but once the springs were fouled, the old dream would disappear.

Yates drove the pickup to a stand of oaks and walked toward a cave he remembered from childhood. The land was flat and semiarid, stubbled with grass and marked with limestone outcroppings; this prairie was a buffer between East and West Texas, between cotton and corn fields and rock-strewn hills with topsoil so thin and fragile you could scrape it away with the heel of your boot. Along the bed of Slaughter Creek, which ran through the property, you could actually see the start of the aquifer recharge zone, see where the water disappeared beneath the rocks, reappearing a few miles east.

“I’ve been an environmentalist all my life,” Yates said as he reached the mouth of the cave—a sinkhole, really, opening into the earth like a porous gray morning glory. Yates could hear the aquifer gurgling. He tossed a small rock into the cave’s mouth and heard the splash. “Ranch people know enough not to pollute the water or contaminate the land,” he said. “We’re not stupid.”

Dividing the Spoils

In the seventies small-town attitudes caused Austin to ignore the growth on its outskirts. Now the city finds itself ringed by residential developments, called municipal utility districts (MUDs), over which it has little or no control. A lot of the trouble started when Gary Bradley put together the Rob Roy development in the hills above Lake Austin. He almost lost his shirt but was saved when a busing scare turned the property into a white-flight mecca. Bradley took the money and headed south to the Circle C Ranch, which was perched atop the Edwards aquifer. He hired power broker Ed Wendler, Sr., to put together a MUD, and Wendlerville, as it came to be known, was born. Then Bradley became embroiled in a fight with environmentalists, who thought they could control growth by stopping it, and with Austin’s old-line developers, who had staked their fortunes on a huge MUD north of town.

The $100 Million Circle

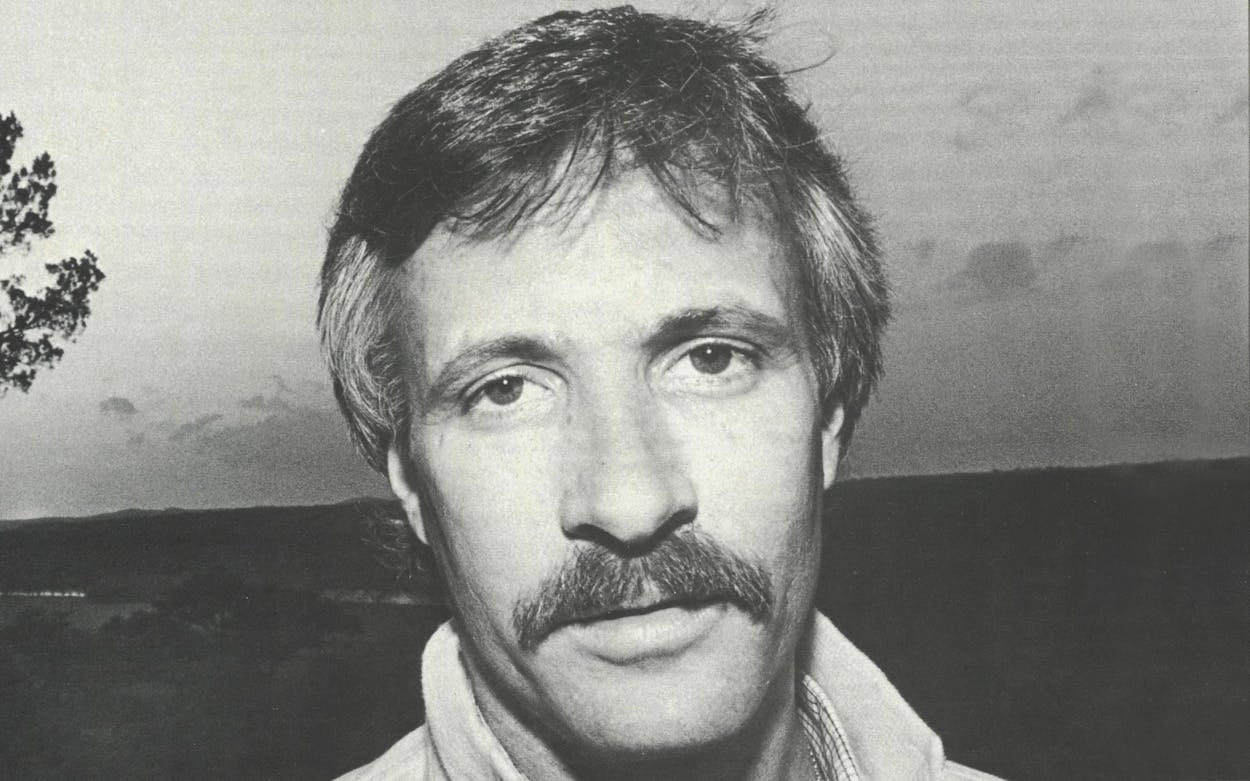

Calling Gary Bradley stubborn and strong-willed is like calling the Pacific wet. By the time he was seven he was working the family farm near the West Texas hamlet of Amherst, and by the time he was fifteen he was managing it while his daddy, Wild Bill Bradley, took off to New Mexico to drink and trade horses with the Mescalero Apache. Gary was the smallest kid in his class and one of the toughest, brightest, and most popular. He was one of those rare children who are possessed by a sense of destiny long before they understand the word.

For three years running, his cotton and maize crops were destroyed by hail. “It was a maturing experience,” he remembered. “You work your butt off with that crop, you’re with it all day every day, then one night about three o’clock you hear the hail hitting the roof. You sit there the rest of the night, trying to imagine what’s happening to the fields. There is no feeling like it. It’s the end. When it does the same thing three years in a row, it’s time to park the tractor.” He remembered one black morning sitting on high ground watching a banker from town cruise by in his Lincoln. He remembered his sense of rage. “I had done the best I could, and I had failed,” he said. “One day soon I’d be standing before that banker, groveling. I’ve thought a lot about where I am today, and I know it started with that experience. I strive to be in a controlled posture.”

Bradley’s mother was a pillar of the Baptist church, as pious and long-suffering as Wild Bill was lovable and roguish. Wild Bill’s brother—Gary’s Uncle Jack—had inherited their father’s business acumen and made a fortune. Gary worshiped his dad and was fascinated by his uncle. He later liked to regale his pals in the real estate business with a story of how his uncle supposedly cornered the funeral-home market in one West Texas town. Torn between the best and the worst of these family traits, between the macho and hard-living outdoorsman who never cared for material wealth and the hard-nosed financier who measured everything by it, Gary Bradley’s life was a complex balance of conflicting forces. “He had a James Dean image,” said John Wooley, Bradley’s partner in Rob Roy, a successful development just west of Austin. “It was a dominating theme in his life—fast cars, women, flash.” One night at a Mexican drive-in movie, when he was still in high school, Bradley made a promise to his best friend, John Norwood, that he would make $1 million by the time he was thirty, and then Bradley and Norwood would fly to Los Angeles, where Bradley would buy a Ferrari. The Ferrari became Bradley’s vision of attainment, like Gatsby’s green light.

When he got out of the University of Texas, Bradley wasn’t really sure whether he wanted to be an investment banker or a rock star. He had majored in finance with the notion that he would probably end up wearing three-piece suits and living near Wall Street with an aspiring actress who looked like Olivia Hussey (who starred in the 1968 film version of Romeo and Juliet). The only two things he knew for certain were that he wasn’t going back to the family farm and that he was going to get rich. He finally took a job as a researcher for a syndicate of real estate dealers in Austin who specialized in buying and selling undeveloped, raw land.

By the mid-seventies Austin’s real estate market was about to take off, though from all appearances the opposite was true. The generation of developers who taught Bradley and other young hotbloods how to deal land had built small empires on what they called Chinese paper—a big promise, a little down, a quick sale. Most went under with the oil embargo and recession of 1974, when interest rates climbed past 12 per cent and bankers got tight with money.

The situation had improved by 1977, when Bradley and John Wooley teamed up to develop Rob Roy, but there was still no indication of what was to come. Located in the hills overlooking a scenic bend in Lake Austin, Rob Roy is considered by many developers to be the seminal land deal in Austin real estate history—financially, environmentally, and politically—but according to John Wooley, it was “just a series of comical accidents.”

The two men, by then in their late twenties, bought the first small piece of the Rob Roy Ranch hoping to make a quick sale so they could pay back a bank loan. The bulk of the ranch was owned by two brothers-in-law who lived in New York and Philadelphia. They had purchased it from LBJ’s old crony Ed Clark of Austin. “There was a big environmental movement in Austin at the time,” Bradley recalled. “Everyone was getting cold feet.” Bradley and Wooley decided to take the big plunge. They traveled east with a standard house contract and $100 earnest money and came back owning the option to the entire ranch. Ed Clark agreed not to foreclose if they could get current on the debt of about $1.2 million. They had some credit with local banks, and Wooley’s stepfather gave them a $1 million unsecured loan to satisfy creditors while they went through the long process of planning the development and trying to get it approved by the city.

By the spring of 1979, however, the Rob Roy development was on the verge of collapse. City manager Dan Davidson (who later took an executive job with competing developer NPC) fought Rob Roy at every turn. The city staff insisted that the development conform to Austin’s standard code for wide streets with curbs and gutters. “This was the Hill Country,” Bradley argued. “Wide streets would have ruined the natural beauty of the land and caused pollutants to collect and run off into Lake Austin.” The developers presented an alternative plan that had paved country lanes and curbs set flush with the pavement so the runoff would water lawns. Their plan got the support of many environmentalists, but the city staff was unyielding.

Because of the enormous cost of preparing plans for the development, Bradley and Wooley were nearly $8 million in debt. The banks were threatening to call in their notes, and on top of everything else, Bradley was laid up in Brackenridge Hospital, throwing up blood and contemplating a question that had been bothering him lately: did that promise to John Norwood mean he had to make a million before his thirtieth birthday, or did it include the months leading up to his thirty-first?

What Bradley did next went unnoticed, but it was entirely in character: he borrowed $15,000 and gave it to the University Baptist Church. Dr. Gerald Mann, who was the church’s pastor at the time, recalled, “He said he’d promised the Lord that if he became successful, he wouldn’t forget Him. Then he handed me an envelope.” Years later Mann learned that Bradley, far from being successful, was hanging by his fingernails. “When you’re getting whipped,” Mann said, “do something different, so Bradley borrowed enough to stay afloat, then borrowed an extra fifteen thousand dollars for the church. He wasn’t trying to buy God off, but he had changed his attitude toward faith.”

If Bradley was hoping for a miracle, he got it. A few weeks later, after he had escorted each council member to the development, the city council overruled its staff and approved Rob Roy, country lanes and all.

But Bradley and Wooley weren’t out of the woods. Over the next several months only a few lots sold. Then, while the two developers were spending the Christmas holidays in Hawaii, a second miracle occurred. Rumors swept Austin that busing was imminent in the Austin school district. The only escape was the West Lake Hills school district, and Rob Roy was far and away the largest available development in it. “We had the only game in town,” Wooley said. “When we got back from Hawaii, it was like we had just opened a new Baskin Robbins across from the playground.”

Over the next thirty days, Bradley and Wooley sold more than 100 of their 247 lots. By the time they sold the next-to-last lot, in 1982, the remaining one was worth the $1.2 million they had paid for the entire ranch. They ended up making a profit of nearly $15 million.

Bradley remembers 1979 as the year he kept his promise: he pocketed his first million before he turned 31. “I went from puking blood in 1979 to fifty million dollars in 1983,” Bradley recalled. That was when he called John Norwood and said, “It’s time.” The next day they flew to Los Angeles and drove home in a jet-black Ferrari.

It is a chicken-or-egg question whether the developers caused Austin’s uncontrolled growth or merely responded to it. But there is no question about the boom itself and the resource that spawned it. It wasn’t computers or high tech or even all that “money talks” talk about making the University of Texas world-class, though those factors contributed. It was raw land. The hundreds of millions of dollars that have been made in Austin in the last few years have been made by selling dirt.

“A dozen developers in this town will make a hundred million each in the five-year period we’re in right now,” said Dick Benson, a former University of Texas student body president who made it big as a developer. “Dozens of others will make a paltry five to ten million. I’m talking authentic, national-level big bucks.”

Stories of new fortunes appear with the morning paper. There is an Austin dentist who is said to have made $20 million on raw land deals (including a bird sanctuary). Austin developer Walter Vackar put up $200,000 earnest money to secure a $6 million deal on the undeveloped balance of a huge shopping center called Barton Creek Square. When his proposed expansion was approved by the city council, less than six months later, the land value rocketed to $16 million. With the announcement in the early part of 1984 that 3M Corporation planned to build a major office and research and development center near Lake Travis, west of Austin, two novice developers who were about to abandon a land deal suddenly had a $6 million profit.

Charles Marsh, a developer who moved to Austin after the Houston land boom played out and whose grandfather once owned the Austin American-Statesman, said, “The real play has been flipping land deals. People borrow money to make a small down payment on raw land, then sell it for double or triple what they paid before the ink is even dry on the contract. People have made one, five, even twenty million dollars.” Marsh didn’t say how much he has made, but it is ten times what he projected. “It’s like the Klondike—that same fever pitch,” he said. One of Marsh’s deals involved a piece of land he bought for $1 million and sold two months later for $4 million. He learned a few days after selling that it was worth $6 million. “I tried to buy it back, but the people I had sold to refused,” he said.

The key, of course, is knowing what a piece of land is worth. Like gold and silver, land has no intrinsic value except the value the market puts on it at the moment. “There are two ways to make money on real estate,” said architect-developer John Lloyd, another veteran of Houston’s boom who is rumored to be in Austin’s $100 million circle. “Buy when the price is right, or sell for more than it’s worth.” Old-line developers like Bill Milburn were primarily homebuilders who bought land because that was the only way they could get lots on which to build, but hotshots like Gary Bradley changed the dynamics of the game. Bradley had never built a house—he didn’t even own one. But he recognized the alchemy by which a few basic services, such as water and sewer lines, greatly increased the worth of raw land, and he refined the necessary political skills to see deals through the various government channels. Until Bradley came along, few had considered the enormous profits in buying huge tracts of land for the explicit purpose of resale. Bradley carved a place for himself in a market that the old-liners had once monopolized. Needless to say, that did not make him popular with the old guard.

The speculation was fueled by easy money. According to one developer, “Bankers in this town were chasing us down the street trying to loan money. You could flip a deal in Austin with little or no money. Some people didn’t even have enough to pay their lawyers, but they knew they could flip a deal before the first payment came due.” It wasn’t just the banks; the savings and loans were also in the play with a lot of ready cash. There were other factors in Austin’s boom too, like the election of pro-growth mayor Ron Mullen, a moderately pro-growth city council, and Governor Mark White, who led the raid that captured Austin’s big prize in the high-tech industry, the Microelectronics and Computer Technology Corporation. Finally, there was a watershed in the environmental movement. As one developer said, “The best and brightest members of the movement all turned thirty-five and went to work for us.”

The City Loses Control

In the midst of the frenzy, the old Austin dream died. The city started growing faster than it ever had. Many of the old politicians didn’t recognize it, but there was a new electorate in Austin, and the newcomers didn’t share the dream of first love at Barton Springs, cold beer at Scholz’s, and picnics under the pecans. One recent immigrant had been heard to suggest semi-seriously that if the city gave up on Barton Springs, the developers could give the city eleven comparable swimming pools—and fill them with Perrier if necessary.

It wasn’t only the size and dimensions of the city that had changed in ten years: its heart and texture had changed too. The center of town used to be Sixth and Congress; now it was FM 2222, four miles north of downtown. Ten years ago FM 2222 was where the boondocks began, and the only people anyone knew living north of it were dope dealers. Now it was Main Street for high-tech migrants who had moved to Austin to work for IBM, Tracor, and Texas Instruments. According to one estimate, nearly 40 per cent of the newcomers were from out of state, and 5 per cent were from another country.

Theirs was a new culture, with a new lifestyle. They didn’t care if a skyscraper blocked their view of the Capitol building. Some probably weren’t aware that Austin had a Capitol building. Their center of orientation was the new suburban shopping centers with theme restaurants, computer stores, and aerobic dance studios. Their lifestyle was given to hot tubs, not Barton Springs. They had no feel for local politics and no interest in it except when they were directly affected. Ben Barnes, at his most recent Christmas party, took an informal poll of his guests, who were residents of Estates Above Lost Creek, a ritzy new subdivision in the hills west of Austin that he and John Connally had built. Half of the guests were surprised to learn that Barnes had once been the lieutenant governor of Texas.

If the old dream lingered among hardcore environmentalists, the new reality prevailed. Many wouldn’t acknowledge it, but Austin’s quality of life had improved in the last ten years. That sleepy little college town had turned into a state-of-the-art living experience. Rather than becoming a classic Sociology 301 slum, Austin’s inner city had prospered. There were delis and fresh fish markets, flower shops and great bakeries. Sixth Street’s skid row was now a colorful promenade of stylish bars and eating places. The shores of Town Lake were landscaped and manicured; hike-and-bike trails laced the riverbanks and the creekbanks of the inner city, and there was an excellent parks system with free neighborhood swimming pools and warm springs. There were free concerts in the parks, a symphony orchestra, a first-rate concert hall, and a lot more.

True, Austin had serious problems—there was a shortage of low-cost housing, integration problems in the schools, and regular disasters with overloaded sewage-treatment plants. But most noticeable to longtime Austinites was the traffic congestion. The construction of the MoPac expressway on the city’s west side destroyed some of the old neighborhoods, but at least it provided a way to get from South to North Austin without traveling the interstate. You still couldn’t go east and west: the environmentalists and no-growthers had blocked those attempts and now they were caught in the grid with everyone else.

For years Austin had been controlled by a small group of downtown businessmen and old-money patriarchs, mostly homebuilders and car dealers, who handpicked politicians and ruled from the back rooms of bars like the Headliners and the Forty Acres Club. Back then, there wasn’t a whole lot of money—few families were spectacularly rich—but most were comfortable in a small-town sort of way. There was trouble in paradise though. The economy was stagnant, and more than 50 per cent of the land in the city was tax-exempt, which shifted the burden to homeowners and small businesses. The city needed to broaden its tax base. So the old guard decided to try to attract the kind of industry that best fit their image of Austin: clean, smokeless, campus-style industry. There was no such word as “high tech” back then, but that’s what it was.

Through most of the fifties, sixties, and early seventies, the old guard prevailed. But in 1975 a former UT antiwar leader named Jeff Friedman put together a coalition of students, liberals, and minorities, and the establishment fell. As mayor, Friedman got after big business. Giants like IBM, Tracor, and Glastron, who at the invitation of the establishment had settled outside the city and thus avoided paying their share of taxes, were annexed. The council nullified an outdated World War II agreement that gave developers rebates on the cost of water and sewer lines. Zoning restrictions were tightened, forcing developers to work with neighborhood groups. If Austin had to grow —and this coalition of freethinkers still wasn’t convinced that it did—it would at least grow right.

In 1975 the coalition began to assemble the city’s first master plan. It was supposed to direct growth, maybe even inhibit it, but in fact it did neither. Rather than limiting Austin’s growth, the plan limited its vision. The master plan was finally unveiled two years later, but it lacked the force of law—a key mistake. It recommended a linear north-south growth corridor along Interstate 35, which would protect both the rich farmland to the east and the environmentally sensitive hills and watersheds to the west. When the plan was announced, land values along the growth corridor skyrocketed, and developers naturally started looking for better opportunities. The hills were irresistible—did the master planners really believe all those prima donnas of the high-tech trade wanted to live along the interstate? Apparently nobody had told the planners about supply and demand.

The city’s loss of control was hurried along in no small way by the emergence of a full-blown, articulate, and politically powerful environmental movement—the only one of any significance in Texas. It had gotten started during the 1971 political campaigns and had been a major force in the election of the Friedman council. The focus of the movement shifted away from the city during the mid-seventies with the building of the South Texas Nuclear Project 150 miles southeast of Austin in Matagorda County, which the city was helping to finance. But what brought the movement back home were two blatant violations of the master plan: the approval of Barton Creek Square, southwest of Barton Springs, and the approval of the Motorola plant in Oak Hill, just over the ridge from Barton Creek.

The mall was a remarkably ugly and featureless shopping center located on what used to be one of the most scenic hillsides in Central Texas. By the time it opened in the summer of 1981, the hillside had been turned into an oily sea of concrete over which gentle Hill Country rain spilled on its lonely way back home. The developer had promised that the runoff would be cleaned by filtration ponds before it entered the aquifer, but to this day no one has been able to prove that the filtration system does the job.

Outraged, the environmentalists boycotted the mall, but that was ineffective. A group that included environmental lawyers Ken Manning and Wayne Gronquist organized the Save Barton Creek Association. Together with the Sierra Club and a local environmental group called the Zilker Park Posse, they pressured city hall for a moratorium on building within the Barton Creek watershed. A citizens’ task force dominated by environmentalists subsequently drafted a Barton Creek watershed ordinance, far and away the most restrictive in Texas. It set density limits for residential development (generally one unit per three acres) and limits on the amount of land covered by material that causes runoff (impervious cover limits) for commercial development. About a year later, a second task force—this one dominated by developers—drafted additional ordinances to regulate the lower five creeks in the aquifer recharge zone (from north to south, Williamson, Slaughter, Bear, Little Bear, and Onion). The ordinances were far tougher than any others in the state, but none limited density, which environmentalists believed was the key to protecting the aquifer.

The environmentalists weren’t satisfied. What they really wanted was to stop all development near the aquifer. They got a chance in the spring of 1981 when a lame duck city council approved the proposed Motorola plant in Oak Hill, an unincorporated town south of the Austin city limits. As it happened, Gary Bradley played a part in the Motorola fight. Not long after Rob Roy was approved, Bradley was appointed to the city planning commission. He perplexed a number of people, especially his fellow developers, by adamantly opposing the development’s utility plan. But one person who was not surprised was Ken Manning, who had gone to work for Bradley and Wooley a year earlier. Since only about 15 per cent of Manning’s time was devoted to the two developers, Bradley and Wooley were in effect subsidizing Austin’s environmental movement.

Bradley’s opposition to Motorola strained his relationship with Wooley, who didn’t trust his partner’s motives. “He didn’t like the fact that the developers were outsiders —they were Canadians,” Wooley said. “I kept telling him, ‘Look, this is a great opportunity; we have a lot of land out there,’ but Bradley liked the fact that the Motorola people had come to him on their knees. Plus it made him a hero with the environmentalists.”

In retrospect, there was never any doubt that the outgoing city council would approve Motorola. Except for its location, on the old Patton Ranch, well outside the growth corridor, the plant was the sort of clean industry the master plan had envisioned. Frustrated by their defeat on Motorola, the environmentalists made a grave tactical error: instead of compromising and attempting to cut their losses, they opposed the development of the remaining parts of the Patton Ranch. By pressuring the city to limit water and sewer lines, they inadvertently forced the city into an arrangement that paved the way for the development of thousands of additional acres, including the land over the Edwards Aquifer.

The environmentalists were refusing to face a critical point: cities in the Sunbelt were growing inexorably, and someone had to pay for costly capital improvements such as sewer and water systems. While most taxpayers agreed that growth outside the city limits should pay for itself, the mechanics were not that simple. Growth could be paid for in three ways. The traditional method was for developers to take out loans to build sewer and water lines and recover their expenses either by getting a rebate from the city or by passing the added costs along to the people who bought the new homes. In the past few years, soaring interest rates had made that option economically unattractive. A second way was for the city to annex the development and pay for the services through the sale of low-interest, tax-exempt bonds. But that required voter approval—not a sure thing in Austin. The third option, which had become popular in recent years, was for the developers to form municipal utility districts (MUDs). Legal subdivisions of the state, like cities and counties, MUDs were authorized to levy taxes and sell bonds to pay for water and sewer systems. People who bought homes in new MUD developments paid for the retirement of those bonds. From the point of view of a city government, MUDs were not a desirable option because they caused cities to lose taxes and they vastly complicated utility planning.

Legally, however, cities could do little to stop MUDs. Under state law, if a city refused to annex a development, the developer had the right to request a MUD. If the city refused to approve it, the developer could go to the state to get approval. Austin’s policy was to negotiate benefits that a developer might not otherwise find agreeable in return for speedy approval of a MUD. With that kind of leverage, developers were usually willing to donate parkland, give the city some zoning approval, or pay their share for oversize lines to fit into the city’s system. That was what happened with the Patton Ranch.

The developers of the Patton Ranch asked for city services. The new city council refused. The developers then asked for a MUD. Again the city refused. But Austin was in a box. The city was broke, and it was apparent that the environmentally concerned voters would turn down additional bonds, as they had been doing for the last several years. Afraid that the developers would go to the state, the city made a deal. The developers got the city’s blessing, and Austin got a big enough sewer line to grow even farther south—and farther outside the growth corridor.

The day that the Patton Ranch deal was struck, the door was opened for Bill Milburn and NPC and anybody else with property along Williamson Creek to start development over the Edwards Aquifer. An uncompromising environmental movement linked with a toothless master plan created a lethal paradox for Austin: citizens with the best intentions had started out to block what they perceived as bad and had ended up making it worse. Within a few years, Austin was ringed by MUDs, hardly any of them corresponding to the master plan, none of them paying city taxes. The master plan created a vacuum at exactly the same time that Austin began to attract high-tech industry. Into this vacuum poured young developers and skillful lobbyists. Within those short years they all became rich beyond their wildest dreams.

The Power Broker

Bradley wasn’t the only one who got a leg up in 1979. That was also the year when business took off for Ed Wendler, Sr.

Ed Wendler didn’t look or act like a power broker. Tall and gangling, with a shock of brown hair that he was constantly tousling, he spoke in a good ol’ boy drawl that spilled out so slowly he seemed to be napping between words. He wore jeans and boots and a faded shirt whose origin appeared to be some hospital scrub closet. He claimed to have ESP, and it was true that nothing happened at the courthouse or at city hall that he didn’t know about in advance. “You know how to get something done in this town?” said one developer. “Go to Ed Wendler, Senior, and pay his fee.”

An old-line liberal who was active in the statewide campaigns of George McGovern and Ralph Yarborough, Wendler started a law firm in December 1978 with two old friends and political cronies, Ben Sarrett and Garry Mauro. Wendler and Sarrett had extensive backgrounds in municipal affairs: in the early sixties they had drafted and lobbied into existence the state’s municipal annexation law, which gave cities control of a five-mile-wide border around the city limits, called extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ). Wendler had also served as lobbyist for the Texas Municipal League. Mauro had just been appointed executive director of the state Democratic committee.

Shortly after the firm started, a group of developers and financiers hired Wendler to write an amendment to the state law on MUDs that would permit cities to levy a surcharge on the districts. It was a way to protect the ratepayers of a city from having to absorb the debt of a development; the surcharges would continue to be paid by homeowners in the MUD even after the city annexed the district.

At the same time, the group asked him to draft a new MUD policy for the city of Austin, one that would allow Austin to ask for refinements in return for quick action on MUD requests. “We wrote a wish list as long as a whore’s dream of things the city could start negotiating with,” Wendler said, “things it could require developers to do—land-use planning, environmental aspects, all that stuff.”

In the minds of some, having Wendler write a MUD policy for the city was like asking the fox to install a new security system on the henhouse. Wendler represented some of the biggest developers in town, including NPC and his boyhood chum Bill Milburn. Both Milburn and Wendler had grown up dirt poor in Austin. Milburn had made a fortune, but Wendler had been up and down for years and was just beginning to emerge as Austin’s premier power broker.

His rise as a behind-the-scenes force in Austin politics could be traced to one of the low points in his career. In 1976 Wendler lost a nasty campaign for county tax assessor-collector. Richard Goodman, who had been a popular news anchor at Channel 24, handled Wendler’s media campaign, and they became close friends. When Goodman decided to run for city council the next year, Wendler was at his side. Goodman’s election gave Wendler an inside at the exact moment when the environmentalists and no-growthers were making life hell for developers.

From 1977 until his retirement in 1983, Richard Goodman carried almost all of Ed Wendler’s proposals. Goodman was a liberal, but he believed that the city had to grow. Goodman recalled, “Wendler saw Austin as anti-growth, so we needed a policy to use the MUD mechanism as a way to grow without voter approval. I got the policy passed. I don’t apologize. Without the mechanism our tax base would have been hurt badly. Towns like Round Rock [ten miles north of Austin] would have a population of two hundred thousand. The Austin boom would have happened anyway, but the development pattern would have been different.”

Goodman truly had a gift for compromise. He was able to pull together opposing sides and maneuver a majority vote on almost any issue he championed. Wendler’s son, Ed Junior, became Goodman’s aide and was later appointed to the planning commission. Before long every board and commission was controlled, or at least strategically populated, by people beholden to Senior, as Wendler was called in the inner circles.

Wendler’s power at city hall was derived from his fundamental understanding that council members in Austin’s city manager form of government are basically puppets. The city manager can control their access to the city staff. Part-time rulers elected at large rather than by a single constituency, they must depend on outside experts in making their decisions. When the experts are people like Wendler, who know the rules better than anyone else and who handpick staff aides and commission members, the result is a city council that rubber-stamps whatever is put before it.

Over the next five years Wendler passed seven MUDs, worth hundreds of millions of dollars; his law firm collected its standard fee of $45,000 and 1.2 per cent of the bonds issued by each MUD.

At that time Wendler was one of the few people in Texas who fully understood the MUD mechanism and how it could be used to turn dirt into gold. Raw land in and around MUDs greatly increased in value whenever a development was formed, and Wendler wanted some of the action for himself. Massive land deals were happening under his nose every day, and there was every reason to believe that the law firm could ride the coattails of one of them and make a major score of its own. “We’re going to get rich,” Wendler told his two law partners. At least Wendler was.

Bradley’s Slick Trade

Gary Bradley made no bones about it: he liked being popular. He liked it in high school when they made him class favorite, and he liked it when people talked about what a fine development Rob Roy had turned out to be. He liked making money too, but the money was more like a badge, testimony that here was a man who could do things and do them right.

He also liked projecting the playboy image—the jet-black Ferrari (other young developers drove Mercedes), a swinging singles apartment with a huge marble tub at one end of the master bedroom, trips to Vegas. He wore the uniform of all young developers in Austin—western shirt, leather jacket, starched jeans, and cowboy boots.

But Bradley’s image was starting to cause problems. He liked being glorified by the press, but his remarks put a strain on his already deteriorating relationship with his partner, John Wooley. He sometimes told reporters, “Look, Wooley is the brains and the money. I’m just for show.” He knew he would get credit anyway; he always had. When invitations from political bigwigs and celebrities arrived in the mail, they were addressed to Gary Bradley, not to John Wooley. Wooley had assumed that once he and Bradley got rich, girls would start calling—they did, but they always asked for Bradley. The two partners would walk down a corridor at city hall, and people would smile and wave at Bradley and, likely as not, ask Wooley, “Do you work for Gary?”

Bradley had a way of making people love him and hate him all at once. He was temperamental and impatient, and he had been known to threaten those whom he perceived to be enemies. Friends told of an incident at a party when Bradley pulled a .357 magnum on a chap to whom he had taken a strong dislike. “Some people think he comes on like a prima donna,” said Bradley’s friend and spiritual adviser, Dr. Gerald Mann. “Two things get him in a lot of trouble. First, he’s a perfectionist. The other thing is, he’s very bright. He’s like a chess master, always thinking about four moves ahead. He gets impatient when others don’t see things as quickly.” His self-righteousness came from honest conviction, but it didn’t win him many friends—especially among older, more established developers.

There was another Bradley, though. He worked fifteen hours a day, and for relaxation he drank beer with a close-knit group of mostly male companions—Doyle Wilson, a carpenter from Amarillo who had made millions in the Austin development game; Mitchell Sharp, the Bradley development lawyer who had met Gary their first year in college; and James Gressett, the firm’s devoutly religious accountant, who had also known Gary since college. They were old and trusted friends, good and decent people who shared a pride in what they had accomplished and were awed by their own success.

Early in 1981, while Bradley and Wooley were still partners, Bradley came up with a scheme that was at once a challenge to his manipulative skills and a masterstroke of public relations that he hoped would silence his critics. Bradley knew the city was looking for parkland along the shores of Lake Austin, and he also knew that a perfect site was about to go on the market. It was part of the old Resaca Ranch, owned by the family of University of Texas regent Robert Baldwin. Most of the 315 acres looked like a park—two hilltops spilled down to a manicured pasture with giant pecans and then to 3500 feet of shoreline. Baldwin wanted $3 million cash for the land, a fair price but one that the city could not immediately afford. Bradley and Wooley planned to use their company’s credit to buy the property, then cut a deal for the city to take the choice 215 acres along the lakefront. After a bond election called for that purpose, the city would repay Bradley and Wooley the $3 million, and the developers would get to keep the other hundred acres free, for the short-term use of their credit.

Wooley loved the deal, and so did the city. But the Baldwins had planned to build a compound on an adjacent thirty-acre hilltop, and they weren’t wild about having a public park next door. They began to pressure city hall to kill the deal. Wooley remembered, “When Gary heard Baldwin was lobbying against us, he went crazy. How dare they try beating Gary Bradley at city hall! Things got so heated between Bradley and Baldwin that the whole deal nearly fell apart. Actually, we could have made a lot more money if Baldwin had torpedoed our deal with the city, but Bradley was dead set on getting even with Baldwin. Getting even was a big thing with Bradley.”

By the time the city finally approved Resaca in the fall of 1982, the relationship between Bradley and Wooley was strained to the breaking point. It finally snapped in October, and the partnership was dissolved. Bradley felt beaten down. He was tired of battling the city bureaucracy, and he complained that the ordeal of city politics was driving him to an early grave. He was at odds with a number of people who were convinced that he had ulterior motives. And he still hadn’t made any inroads with established developers, who were turned off by his style.

But just as Wooley moved out, a new player, Ira Yates, moved in. Yates had decided it was time to develop the Circle C Ranch, which his mother had bought in 1946. He had been impressed by Bradley’s handling of Rob Roy, the way Bradley maneuvered it through city hall and the way the development turned out.

Yates teamed up with Bradley, and they agreed to hire Ed Wendler to lobby for them. The Circle C project was on its way.

A Conflict of Interest

In the fall of 1982, Ed Wendler, Sr., was already considering which candidates to back in the city council election the following spring. His clients hadn’t thought about it yet, but Wendler knew that when he announced the massive project he was planning for the land over the Edwards Aquifer, all hell would break loose.

It was hard to dispute Wendler’s view of himself: he did good for Ed Wendler by doing good for Austin. He loved the city and laughed when he admitted he hadn’t been to Barton Springs since he was a kid. He gave every appearance of being a card-carrying liberal, but like other liberals in their fifties, he was tired of being poor. He had watched young developers like Bradley and Wooley become something the liberals had never dreamed of becoming—filthy rich.

Wendler’s meal ticket on the council, Richard Goodman, had fallen on hard times. He had been arrested the previous summer after a bizarre drug-induced shoot-out with a garden hose, and he was now a lame duck, frequently absent from council meetings. The incumbent council was not necessarily anti-growth, but it was so wishy-washy that it amounted to the same thing. Former council member Lowell Lebermann, a symbol of old Austin politics, was running for mayor, but Wendler was backing Ron Mullen, and so were most of the developers, including Gary Bradley, who was a good friend of Mullen’s.

Wendler had formed an informal club of developers, each of whom paid him $1500 a month to monitor city hall and publish a newsletter that he circulated at their monthly meetings at Steak and Ale. “He advised all of us which candidates to back, and almost without fail they got elected,” John Wooley recalled. But this was a new day in Austin, and Wendler was going for new stakes. This time he intended to elect all seven council members. He knew that he couldn’t count on all seven to vote his line every time, but all he needed was a majority. He needed a steady flow of information and small favors, and he needed to know that when he spoke, every member of the council would listen.

One of Wendler’s candidates, Roger Duncan, took some selling. Duncan was regarded as a rabid environmentalist, though Wendler had always found him agreeable to pet projects. “I like Roger,” Wendler said. “I disagree with him a lot, but Austin needs a Roger Duncan.” Duncan gave the council the sort of liberal-conservative balance that Richard Goodman had once provided. Duncan could compromise, especially on Wendler-backed projects.

In the mayor’s race, Mullen was openly pro-growth, but he had a problem: an agent working for his insurance company had sold a $4.5 million policy to Bradley and Wooley, and Lebermann was certain to dog him with the issue.

Lebermann had put together what many regarded as an unbeatable coalition of students, minorities, neighborhood associations, old West Austin money, and downtown business interests—the factions that ten years before could easily have captured city hall. But Wendler recognized something that traditional politicians had not accepted: it wasn’t ten years ago. Wendler’s seven candidates were swept into office in the spring.

That was also when Wendler became involved in a $100 million project for Bill Milburn. It was called the North Austin MUD No. 1, and it was probably the most complex municipal utility district in state history. At almost a thousand acres, it was certainly one of the largest near Austin. Milburn and NPC had fairly well dominated the land market north of Austin and into Williamson County almost as far as Cedar Park. But one weekend, as Wendler was showing his brother, Kenneth, the boundaries of Milburn’s North Austin MUD, he spotted a piece of land that other investors had overlooked. “The second I saw it I knew it flowed naturally into Bill Milburn’s MUD,” he said. Wendler had been waiting to find a bird’s nest on the ground, and that was it. He quickly and quietly found a group of investors among his friends and took a thirty-day option on the land. The 112-acre tract was in a package being submitted as a proposed service area for Milburn’s MUD, and Wendler got it approved by the city. He neglected to mention to the council (or to his law partners) that this time he owned a piece of the action. Ed Wendler, Sr., and his brother each made more than $2 million on the deal.

Gary Bradley didn’t learn about Wendler’s big score until the fall of 1983. If he had known about it sooner, he might have realized that hiring Wendler wasn’t necessarily in his best interest.

Wendlerville

In February 1983, Wendler began putting together a package southwest of Austin that came to be known as Wendlerville. At one time it was two 700-acre pieces of land owned by Bill Milburn and NPC. Then Gary Bradley came up with the Circle C, an adjoining piece of property three times the size of the two original pieces combined. Wendler, seeing a chance to collect three fees for what was essentially a single lobbying effort, took on the Circle C.

Though Bradley doesn’t remember it this way, Wendler said he warned the three developers from the beginning that the only way he could represent them simultaneously was if they agreed to ask the city for the same considerations. MUD approval was tricky business in Austin, and Wendlerville was particularly tricky because all three developments were over the Edwards Aquifer.

From the outset, the environmentalists were more opposed to Bradley than to the other two developers, mainly because all of Bradley’s MUD was on Slaughter Creek, while the other two were primarily on Williamson Creek. Both creeks were far outside the master plan’s much-abused growth corridor, but Slaughter Creek, which was farther south, was in the most restricted area of the master plan. Bradley knew that his development had to conform to the lower watershed ordinance requirements: he was limited to five dwellings per acre and had to provide filtering systems to control runoff. But he was taking no chances. He and Yates had their engineers make special plans for recharge enhancement dams that would collect the runoff in ponds, giving it time to be filtered before the water reentered the aquifer. They also agreed to donate seven hundred of the three thousand acres to the city parks department, which would help protect the recharge zone and pacify the council and environmentalists at the same time.

Wendler had assigned each of the developments specific parts of a large-scale utility plan. The utilities would tie into the system that the city had created back in 1979 for the Motorola–Patton Ranch package. In effect, Wendler’s plan gave each developer a way to justify his MUD to the city council. A major justification for the Circle C was a giant sewer line—an interceptor, it was called—that followed the natural slopes of Slaughter Creek.

Until the summer of 1983, everything seemed to go according to plan. Then Bradley fulfilled another boyhood promise and took his dad on an African safari. While he was out of the country, the Circle C ran into trouble. There had been some bickering among the developers before Bradley departed, but it was nothing Wendler couldn’t handle. When Bradley returned, just about the time the NPC and Milburn MUDs were getting final approval, he learned that a wastewater commissioner named Kent Butler had transferred the interceptor from Bradley’s MUD to Bill Milburn’s. That, of course, eliminated much of the rationale for the Circle C MUD. Bradley was outraged. “Milburn didn’t even want it,” he said. Bradley had hired Wendler, for $50,000, to protect his interests and shepherd his MUD safely through the bureaucracy. Wendler assured Bradley that the loss of the interceptor wouldn’t hurt the Circle C’s chances with the city council, but Bradley believed otherwise and redoubled his efforts to ensure its approval.

All through September, October, and early November he lobbied the various boards and commissions that were part of Austin’s complicated process for development approval. At night Bradley and Yates spoke to neighborhood associations and environmental groups, answering questions and reassuring them that neither the aquifer nor Barton Springs would be spoiled.

But as the November 17 date for the public hearing approached, Bradley realized he hadn’t heard a word about how the votes were lining up at city hall. On November 16, Ed Wendler, Sr., telephoned Bradley and announced that he was resigning. “We had been working on Circle C for eighteen months,” Bradley said, “Twenty-four hours before it was time to go before the city council, I realized I’d have to walk in there buck naked.”

Wendler was quitting, he told Bradley, because Bradley was planning to ask the city council for special considerations, and Milburn and NPC had pressured him to ditch Bradley’s project. True, Bradley wanted the city to share the $8 million cost of the recharge dams; he planned to ask for extras to cover drainage costs; he wanted to expand his sewer and water service to include 1400 acres next to the Circle C; and he wanted the city to delay annexation for fifteen years. But he’d also spent months lobbying city commissions to get the requests passed. As far as Bradley was concerned, the city owed him special consideration because he had taken extra steps to protect the aquifer; even the boards and commissions had commended him for a well-planned project.

The environmentalists were already upset by the location of Bradley’s project, but when they learned that he was now asking for special consideration, they were outraged. Ken Manning stayed out of the fray in deference to his friendship with Bradley, but he said privately, “He’s asking for things you couldn’t even get in the growth corridor itself. He’s asking for the sun and the moon.”

Wendler’s resignation was a signal that he was no longer supporting Bradley. With the most powerful lobbyist at city hall openly leaving Bradley’s team, Milburn and NPC lobbying against him, and the environmentalists out to stop him, the city council was sure to resist the formation of his MUD. He didn’t even know if he could count on his friend and supporter Ron Mullen to salvage the deal.

Bradley felt double-crossed. Wendler had timed it perfectly, leaving him hanging on the eve of battle. His motives seemed clear enough to Bradley: “If you take the Circle C out of the Austin real estate market, the only approved projects offering ten to fifteen years’ worth of inventory are those owned by Wendler’s clients—Milburn and NPC.”

Bradley had learned from his network of contacts about Wendler’s land deal in North Austin, and now he realized just how dependent Wendler was on Bill Milburn. What was good for Milburn was good for Wendler, and nothing could have suited Milburn better than stopping a young upstart like Gary Bradley. If the Circle C was blocked, not only would the Milburn and NPC properties in Southwest Austin become more valuable but more development would be forced to the north of town, where Wendler and his clients, especially Bill Milburn, already owned most of the land.

The following afternoon Bradley talked to the council for almost four hours. He left the chamber feeling that he had struck an uneasy truce. The council wasn’t going to help finance the recharge enhancement dams, but it seemed agreeable to some of Bradley’s less costly requests.

Wendler denied lobbying against Bradley, but his next move certainly looked that way. He later admitted, “Well, in Bradley’s mind, I can see how he would call it that.” When the council met on December 8 to vote on Bradley’s MUD, Wendler asked to speak. In what was surely a ploy to intimidate the council, he argued that if it gave Bradley special favors he—Wendler—would be back the following week to demand the same favors on behalf of his clients. He asserted that Milburn and NPC were due as much consideration as Bradley because they were building the city a sewer system essential to the Motorola–Patton Ranch deal. Bradley was only giving the city a park. In executive session Roger Duncan picked up the argument. Since Milburn was building the interceptor, there was no justification at all for a three-thousand-acre MUD so far from the growth corridor.

Bradley had argued that he shouldn’t be penalized because two other developers had failed to ask for something. He’d done the legwork of getting his requests approved by the boards and commissions, and he had been given their support. He was giving the city a free park. Everyone knew Bradley would sue if his MUD wasn’t passed. The mayor backed Bradley, and Duncan dropped his argument. The council voted to approve the Circle C MUD.

Bradley had won the fight, but the feeling of betrayal stayed with him. Maybe it was a premonition: five days before Christmas he learned that the battle wasn’t over. Roger Duncan submitted a totally new Edwards Aquifer ordinance that would make any development economically prohibitive. The Circle C had been limited to five units per acre. The ordinance that Duncan proposed was ten times more restrictive, allowing only one unit per three acres, just like Barton Creek. They were trying to change the rules in the middle of the game.

Bradley Goes to War

The last-ditch effort to stop Bradley was led by the environmentalists. They really thought they could win the fight, even though Ed Wendler, Sr., warned them they didn’t have a prayer. The politicians didn’t seem to understand; the environmentalists were talking about the aquifer—the very word blossomed like an incantation from their lips. “I really do believe we’ve got the mayor behind us on this one,” said lawyer-lobbyist Wayne Gronquist, who had drafted the new ordinance. “I think Mullen would really like to go down in history as the man who saved the aquifer.” The environmentalists had argued among themselves about how far they dared take it. One of them, Joe Riddell, who had served on the task force that drafted the existing ordinance, thought the density limit should be one unit for each forty acres. Should they include all five creeks in the lower watershed, or compromise? Ed Wendler had given them some good free advice: “What you’ve got to do is get ahead of the developers. They’ve already got Williamson Creek, and there’s no way you can stop them from getting Slaughter Creek too. What you’ve got to do is fall back to Bear Creek and take your stand. That way you’ll still save eighty per cent of the aquifer.”

The environmentalists had already discussed compromising on Williamson Creek, where the Milburn and NPC MUDs were located. They had even talked about sacrificing Slaughter Creek, and they might have if the developer had been anyone except Gary Bradley. They had talked, too, about the threat of lawsuits against the city. If the ordinance grandfathered the Circle C, everyone else affected by the ordinance would sue. If the city didn’t exempt Bradley’s MUD, he would sue. In the end, they compromised on an ordinance ten times more restrictive than the ones on the books, but they wouldn’t give up any of the five creeks.

As the battle lines were being drawn, Wendler played the role of the cool, detached professional, conspicuous only by his absence. “I told Milburn and NPC the day the ordinance was submitted that the vote was five to two against it,” he said later. “Why get in a bitter fight, especially when you’ve already won it?”

But neither Wendler nor the environmentalists anticipated the ferocity of Gary Bradley’s response. By the time the council was ready to consider the new ordinance, Bradley had assembled an army of about twenty experts in urban planning and environmental control. Several days before the hearing, Bradley met with the mayor to work out the logistics of the session. It was agreed that the environmentalists would speak first. Bradley calculated that that wouldn’t take long.

On Sunday night Bradley ran his army through an intensive invasion briefing with charts, graphs, and slides. “How many Ph.D.’s do we have?” he asked, and four or five hands went up. As each expert gave his or her spiel, Bradley nodded and made notes. He was psyching himself for his own flamethrower speech, and the words were already boiling in his belly.

It went something like this: It wasn’t Bradley who was the elitist, it was the environmentalists. They said they represented the people of Austin, but what they were proposing for the entire southwest section of Austin was a subdivision of mobile homes. The Circle C was prairie, not hills. Nobody was going to build a $300,000 home on Slaughter Creek. The Circle C was no Rob Roy, and that was what made it a natural. It was estimated that by 1990 the average new home in Austin would cost $277,000, but the homes that Bradley envisioned for the Circle C were in the $100,000 range. One member of Bradley’s staff referred to the development as Bubbaville. The whole aquifer issue was a red herring—it wasn’t water quality, it was aesthetics. It was Barton Springs. Hadn’t he done what he promised with Rob Roy? Hadn’t he established that the structural controls at Circle C would protect the aquifer? When had he failed to show good faith? When had he failed to keep a promise? It really came down to one essential question: who should pay to protect Austin’s most treasured landmark? Should the people who owned land over the aquifer pay the full cost or should we all share it? How much was Austin willing to spend to protect Barton Springs? “They’re not spending a damn penny right now,” Bradley said, his voice rising. “Okay, people, I want you to go in there tomorrow and give them your gorilla dunk!”

As the army was leaving Bradley’s office, council member Mark Rose arrived. He told Bradley that one council member would probably abstain and that it looked as if the vote would be 4–2 against the new restrictions. Roger Duncan was sure to be in a minority. Duncan was ready to compromise, but it was too late as far as Bradley was concerned. Duncan had made himself the enemy, and enemies were to be annihilated. Bradley knew he was going to win, but that was no longer the point. He wanted them on their knees. He wanted them to admit he was right.

The following morning Ira Yates met an environmental engineer named John Mancini at the airport and drove him to a helicopter that was waiting to fly them over Barton Springs and the aquifer watersheds. Mancini had flown in from Omaha at Bradley’s expense and was probably the key witness for both sides, though the environmentalists hadn’t yet realized it. The environmentalists’ main piece of technical data was a study called the Nationwide Urban Runoff Project. From their reading of the study, the environmentalists concluded that density requirements were the only proven method of controlling pollution from urban runoff. That was a serious misreading, as Mancini knew only too well. He had supervised the NURP study.

The council chambers were packed on February 13, the day the fight finally came to a head. The environmentalists knew from the first moment that they were in for a rough time. For one thing, they had expected a large turnout for their stand-up-and-be-counted crusade, but fewer than a dozen supporters showed up. And with the appearance of Mancini in the opponents’ camp, the environmentalists’ one piece of technical evidence, the NURP study, became worse than useless. Bradley’s backers all but filled the council chamber, and they included not only his staff and paid witnesses but also landholders who owned small ranches near the Circle C. Bradley was ecstatic as a white-haired rancher in a worn jacket extended his hand and said, “Young man, I couldn’t say all those things the way you said them, but I want to thank you for what you done.” Wayne Gronquist realized that the environmentalists’ cause was in trouble.

As Bradley had anticipated, the environmentalists needed only about an hour to complete their presentation. Bradley’s side took about four hours, though he had to spread his presentation over three nights.

In his talk before the council, Mancini committed what, in the eyes of the environmentalists, was the ultimate blasphemy: he told them to trust technology. “Urban runoff doesn’t hurt water quality,” he said, “and in some cases, when it is treated properly, it can even help.”

“Depends on the quality of the prostitute you buy,” whispered Bert Cromack, the current president of the Save Barton Creek Association.

Bradley knew that Wendler was working behind the scenes to try to save the reputation of his council insider, Roger Duncan. The night before the final vote, Wendler visited one of the council members to ask him to persuade Bradley to call off the attack. “He knows he has won,” Wendler said. “All he’s trying to do now is destroy Roger Duncan.” Bradley didn’t deny it.

That same night Bradley met with a group of politicians, including Ed Wendler, Jr., who came to his apartment to speak to him about his “attitude.” Bradley had been determined to go into the council chamber kicking and scratching, but the next morning he changed his mind. The council promptly voted 4–2 to remove the more restrictive density requirement from the ordinance. From Bradley’s point of view, the ordinance was effectively dead.

A few weeks later Bradley signed a contract to sell the Circle C to a group from Dallas, who agreed to pay $60 million cash, $50 million of which was profit. That night he and his pals got falling-down drunk on Sixth Street. A day or so later Bradley and his girlfriend left for a vacation in Hawaii. When he returned, Bradley made one more promise. He was never going to fight city hall again.

When the environmentalists assessed the damage, they realized that they had not only lost the battle, they had lost the war too. Wendler had been right. They should have retreated to Bear Creek. That way they would have saved most of the aquifer. If the ordinance had exempted Williamson and Slaughter creeks, Bradley wouldn’t have come at them and they probably would have won. “It’s too late now,” Ken Manning said. “Bradley put on such an overwhelming presentation that he shifted the burden of proof. As it stands now, the city council won’t change that vote until someone can prove the structural controls don’t work. That’s five or ten years down the road.”

By that time, all the land over the aquifer recharge zone will be swarming with developers, many of them no doubt considerably less environmentally sensitive than Gary Bradley. Who knows, in ten years they may devour the entire aquifer, toothless catfish and all. And that will be the end of any dreams—old or new—for Austin.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Austin