Erykah Badu, known variously over the past decade as the Queen of Neo-soul, the Nefertiti of Hip-hop, and the Woman Who Wears That Thing on Her Head, sat on her couch rubbing Blue Magic conditioner into her daughter’s hair, tying clumps together and wrapping them with rubber bands while she talked about the giant, red, mazelike circle painted on the floor at her feet. “Actually, it’s not a maze,” she said. “A maze is designed to puzzle. It’s a labyrinth—there’s one entrance and one way to the center. It kind of looks like a brain. It’s very meditative. The labyrinth is an ancient symbol; you find them all over Europe and Asia. I wanted to create a nourishing environment, a place I could retreat to when things got too busy for me.”

I couldn’t tell if Puma, who is two and a half years old, with light skin and puffed cheeks, was more unhappy about what was being done to her hair or sharing her mother’s attention with a stranger. She squirmed and fussed, stretching her head out of reach, then climbed down and stood on the floor, glaring. The 35-year-old Badu asked Ysheka, one of her assistants, to bring a bottle, and when it came, the toddler climbed back into her mother’s lap and drank quietly.

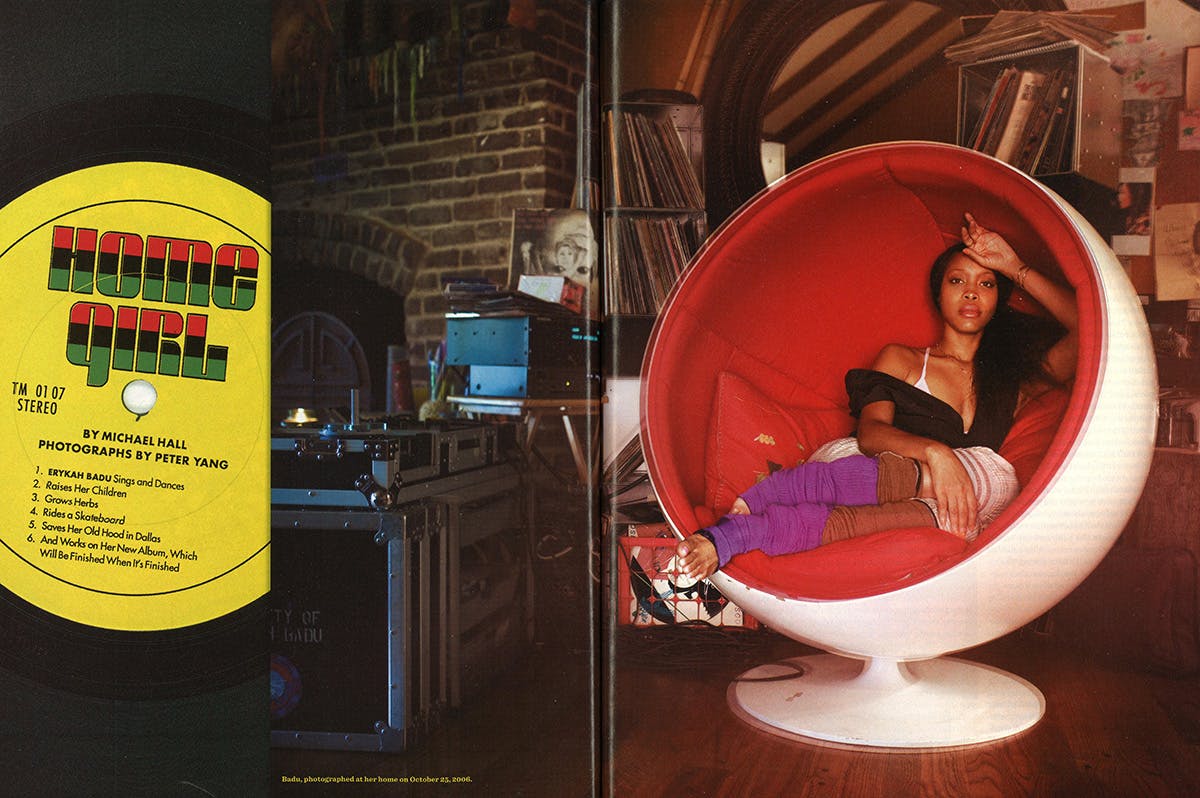

Badu’s three other assistants—Denise, Sharlene, and Alfredo—hustled around in their bare feet, cleaning, making phone calls, getting things ready for the afternoon. It was just after eleven on an October morning at Badu’s house on the shores of White Rock Lake, in East Dallas. I was there to spend a day with her, to find out just what a Dallas R&B star does with her time, especially one approaching her ten-year anniversary in the pop music limelight, a year that by all rights should see her finishing up her fifth album, the one that her record label and her fans have been expecting since 2005.

I had already learned something that morning about waiting for Badu. She had been in her home studio until five in the morning, so we had started our interview almost two hours late. Badu admits that her own conception of the temporal rarely coincides with the one used by people who wear watches. Now, holding her daughter, she talked, again in her own way, about time. “The last ten years have been like a circle,” she said, “going back to Chinese astrology. I got my record deal in 1996, which was the Year of the Pig, and my first album came out in 1997. I was born in 1971, which was also the Year of the Pig. And 2007 will be the Year of the Pig again. I know this year will be special.”

The smell of peppermint incense mixed with the music of seventies Motown songwriter Willie Hutch, which was playing on the turntable in the next room (Hutch was raised in Dallas and later composed the music for the blaxploitation flick Foxy Brown). “I am creative” and “I love myself” proclaimed signs on the wall. “Love Animals Don’t Eat Them” and “Be Green” announced bumper stickers on a nearby stove. A box of art supplies sat on a cluttered table next to a couple of palettes of dried orange and purple paint; on the wall were paintings of and by mom and her other child, nine-year-old son Seven. A piano and guitar sat next to the fireplace, and a hundred thin stalactites of colored candle wax descended from the mantel. A sign near the front door read “God Bless Our Pad.”

The labyrinth lay in the center of the large downstairs room of Badu’s house, what you might call the music-and-art room, though every room there is a music-and-art room. Next to the couch was the study area, with posters (“Emotions,” “Numbers,” “Days of the Week”) and a whiteboard, where Badu teaches Puma, as she did Seven before. Across the room were a child’s keyboard and drums and a large photo of Seven—who looks a lot like his father, André Benjamin, of OutKast—banging on them. On the other side was a collection of some of the magazine covers Badu has been on—Hits, Vibe, plus a huge reproduction of a September 2003 Ebony cover, with Badu in a giant Afro. Next to the covers was a cabinet that held some twenty trophies, including her four Grammys.

A decade ago Badu became one of the biggest R&B stars in the world when she released her debut album, Baduizm, a minimalist soul masterpiece that reached number two on the Billboard pop charts and eventually sold three million copies. Baduizm helped usher in a new movement that some people called “neo-soul”—Afrocentric music with a seventies vibe but a nineties hip-hop edge. It helped that Badu cloaked herself in her heritage, wearing a Yoruba headdress called a gele on her album cover as well as on tour. She would spend the next ten years being a rarity in pop music, a bona fide iconoclast, doing basically what she wanted. She made two more studio albums, each completely different from the one before. Her sound was influenced by Lauryn Hill, of the Fugees, but also Chaka Khan and Joni Mitchell, and she was as likely to draw on Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue as Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. She appeared in movies such as The Cider House Rules. She toured when she felt like it and acted in local Dallas theater. She had two children by two men. She bought a house in Dallas and lived in it.

I noted to Badu that most musicians from Dallas who make it big, from T-Bone Walker to Edie Brickell, get out of town as soon as they can. “That’s what celebrities do,” she responded. “I never wanted to be a celebrity. My first job is not music. I love it; I especially love to perform, especially here. I’m an artist by religion. I paint, draw, sew, design clothes, sculpt, build, and raise children. Music is a great way to make money. But I don’t want to be a celebrity. I want to be able to go to the store and buy some milk. And my heart feels whole in Dallas. I feel connected to my ancestors here. I know who my great-great-great-grandmother was. My son and I did a family tree a few years ago, and it was phenomenal. I found all these photographs. I look like them. I got my eyes from my father. His mother was from Waco. Her mother was from Plano.”

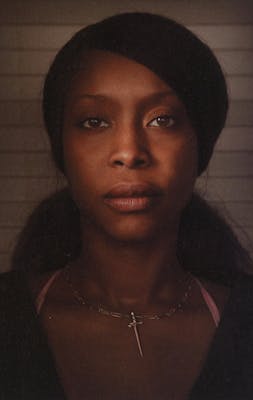

On most of those magazine covers, Badu is elegant and graceful, defiant and iconic, like a sixties “Black Is Beautiful” poster. In person she’s just another five-foot-two, black, thin, pretty, vegan artist with light greenish-brown eyes. For our interview and photo shoot she wore her hair long; her jewelry consisted of a gold bracelet on her left wrist and a silver ring around her left forefinger. She looked as if she’d just come from a morning cruising thrift shops, wearing a black shirt, white plaid pants, purple leggings, and an apron because she’d forgotten to put on a belt. She walked around her house barefoot and began and ended conversations with the word “peace.” There’s no escaping it: The Nefertiti of Hip-hop is a hippie. “I’m into crystals and herbs,” she said, laughing. “I plant herbs, grow them, pick them, dry them, deliver them to people. You would not believe how boring my life is.”

Puma had wandered off during our interview, but now she returned and crawled up into her mother’s lap, hugging her belly. She wasn’t fussy anymore, and Badu held her close. “I got you,” she said. “I got you.”

“You got me?”

“I’ll always have you.”

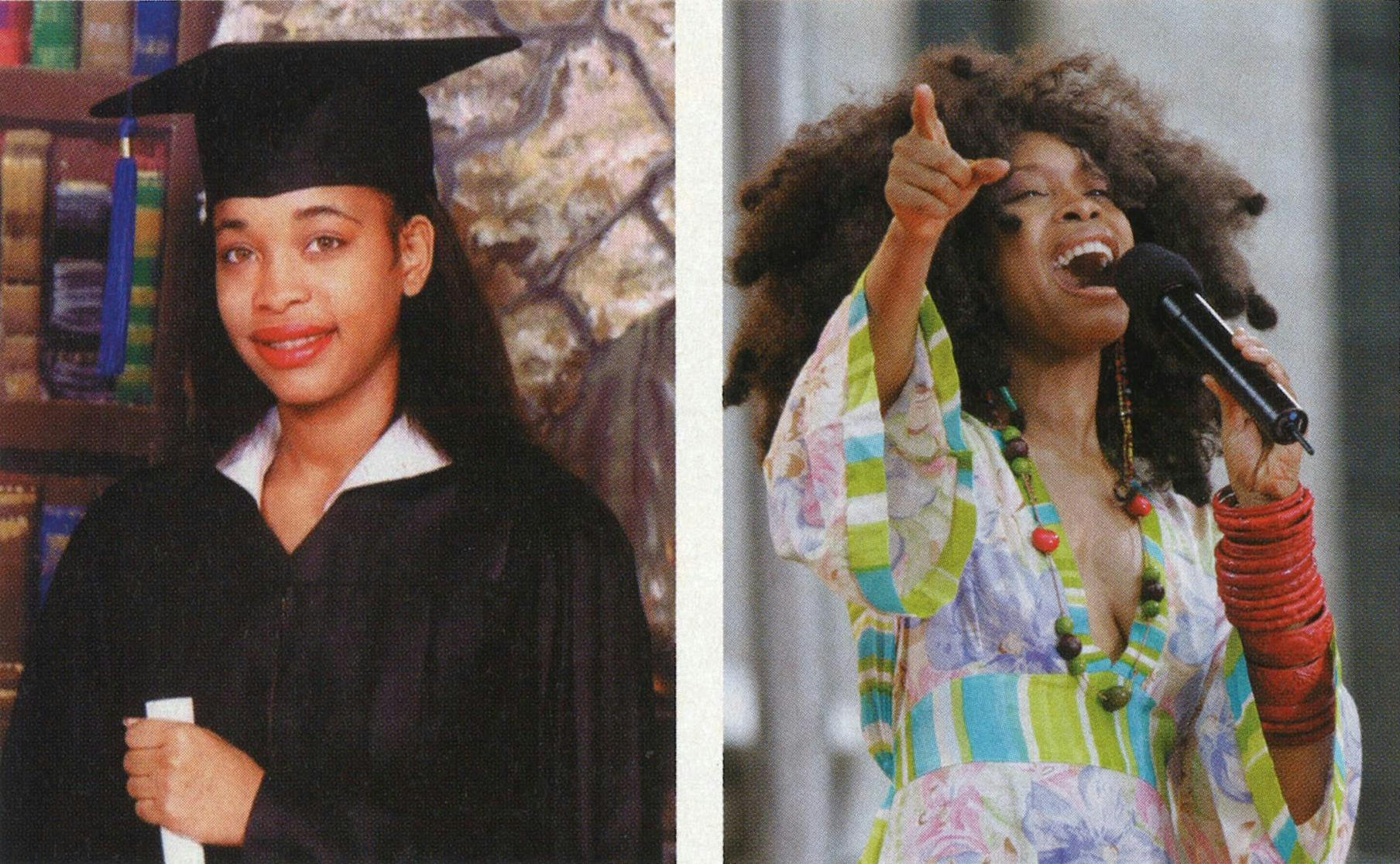

There are artists whose lives are clean and whose art is precise. Then there are artists like Badu. “Sharlene,” she called out calmly to one of her assistants. “Can you do me a favor and put some toothpaste on my toothbrush?” We were late for our next appointment: Badu was going to dance with a class at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts, the former all-black campus that became an arts magnet school in 1976 and that Badu—then known as Erica Wright—graduated from in 1989. Until Norah Jones sold six million albums in 2003, Badu was the school’s most famous alum, beating out childhood friend and jazz trumpeter Roy Hargrove and pop singer Brickell. Badu has gone back to the school many times to speak, but this was the first time she would go to dance.

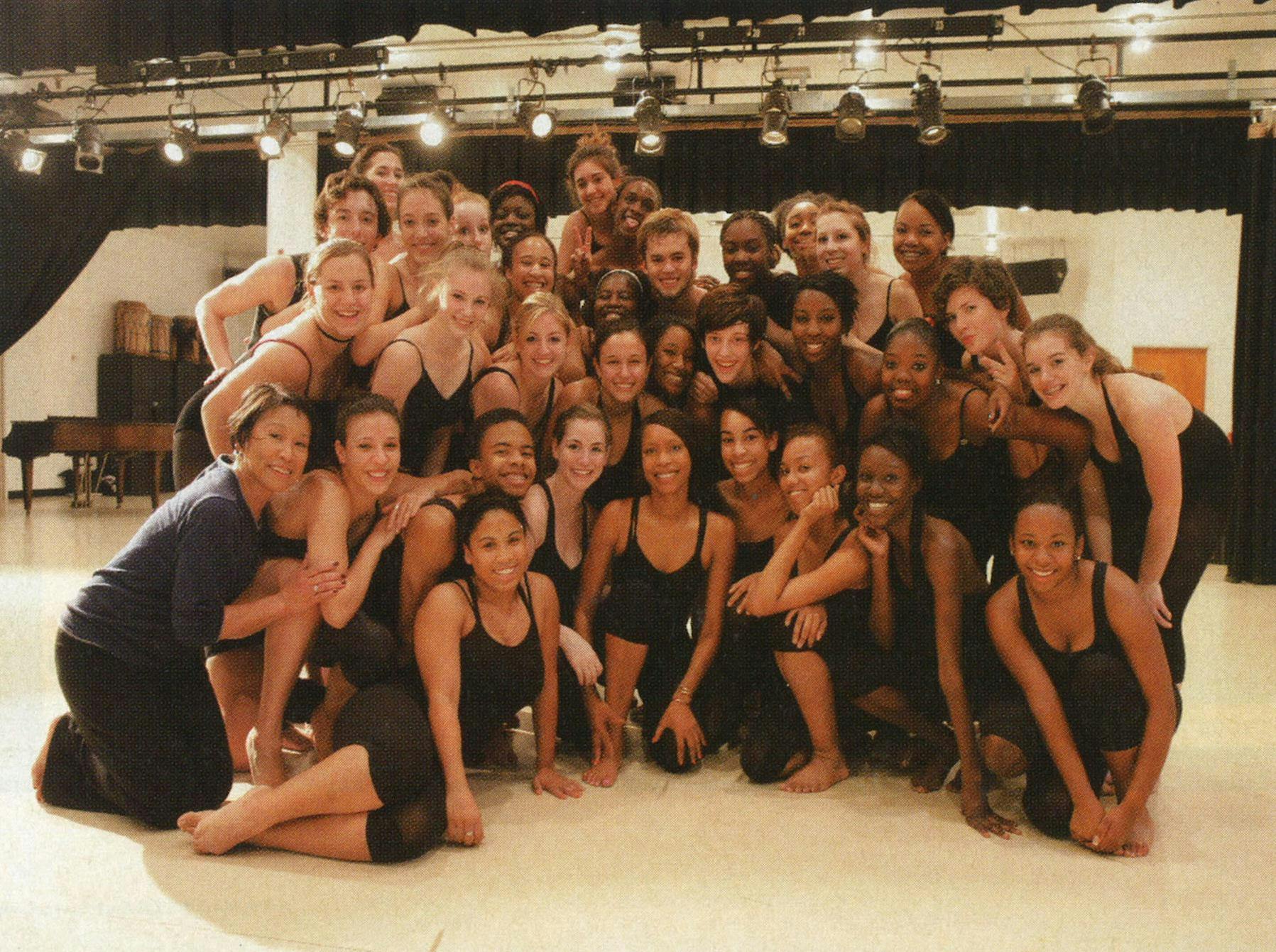

Denise drove, and we sped along U.S. 75 in a drizzling rain to east Oak Cliff, the site of the school’s temporary quarters while the actual campus undergoes a $47 million renovation. Teacher Sharon Cornell was waiting out front. “How you doing?” Badu called out, and walked over and hugged her. She was hustled inside, hailing a couple of former teachers along the way, and then into a dance studio where three dozen teenagers in black leotards sat on the floor waiting. Badu was primarily a dance student here seventeen years ago, though she also did theater and music. The kids—half black and half white, mostly girls—grinned when they saw her and started slapping their hands on the floor and cheering. Badu smiled and waved, walked to the front of the room and hugged her former teacher Lily Cabatu Weiss, then went and changed into a leotard.

When she returned, the students were aligned in rows for warm-up exercises, and Badu slipped into the second one, three kids in. Weiss, a short Filipino American woman who has won several distinguished teaching awards, started the music and energetically clapped her hands, calling out cadences as the students went through a litany of the various exercises—“One and two and circle your arm!”—modern-dance students have been doing forever. Badu had done the same ones two decades earlier and followed along as if she had done them yesterday. When the group started prancing across the hardwood floor, leaping and high-stepping to drills, Badu followed along. By now several teachers had come in to sit and watch. Rosann McLaughlin Cox, a white-haired woman who is the founder of the school’s dance program, said to no one in particular, “See her back there? She looks like one of the babies!”

Weiss kept up the clapping and the banter. “Come on, you guys,” she called. “Life is good! You’ve got Erykah Badu dancing with you!” Badu was clearly as eager to please Weiss and prove herself as the students were. At one point Weiss called out, “You guys, she looks just like you! She is!” As the dancers would gather on the side waiting for the others to cross, Badu acted like a teenager, joking and fidgeting. When a girl fell, Badu hugged her. At one point I heard her say to one of the boys, “How’s your mom?” The boy, named Jabril Johnson, answered quietly, and Badu nodded.

His mother, it turned out, had had a part to play in Badu’s leaving dance behind and becoming a recording artist. After she graduated from high school, she did various things—rapped in local clubs and on a radio station, studied theater at Louisiana’s Grambling State University, taught dance and theater to kids in South Dallas, and worked at Steve Harvey’s Comedy House, in Oak Cliff, selling tickets, waitressing, and sometimes getting onstage to perform. One night Jabril’s mother happened to see her there and called her brother, talent agent Tim Grace. He was impressed enough with Badu’s improv—and then with her rapping and singing—to become her manager. Badu had been performing with her cousin Robert Bradford and they had made a tape; with Grace’s help she shopped it to some labels and landed a deal with Universal. In 1995 she moved to Brooklyn with, she told me, “a backpack and my Daisy Dukes.” She was a hippie girl from Dallas, wearing a T-shirt and jeans, eating no meat or dairy, studying African history, and reading Angela Davis. But now she changed her name to Erykah Badu (for the scat syllables, ba-du, ba-du, ba-du) and began in earnest putting together her sound, philosophy, and image.

They came together on Baduizm, where she used jazz guys like Hargrove and Ron Carter and hip-hop guys like the Roots to fashion something fresh; soon artists like Maxwell and Macy Gray were following her lead. People in Dallas knew that Badu could rap, but on Baduizm she showed she could also sing: vulnerable like Billie Holiday, pop-sexy like Diana Ross, just plain sexy like Chaka Khan. And songs such as “Appletree” were the kind a Natural Black Woman would write:

I don’t walk ’round trying to

be what I’m not

I don’t waste my time trying

to get what you got

I work at pleasin’ me ’cause

I can’t please you

And that’s why I do what I do

My soul flies free like a willow tree

Doo wee doo wee doo wee.

The single “On & On” had the memorable line “My cipher keeps moving like a rolling stone,” which was puzzled over by millions when the song became a number one R&B hit. Universal rushed out a live follow-up that had another hit, “Tyrone,” a novelty song about a bad boyfriend that Badu had improvised onstage in London; it would become a crowd-pleasing feminist put-down anthem.

Her next studio album, Mama’s Gun, was almost four years coming, delayed by writer’s block and Badu being Badu. She began using a line she would pull out when needed: “I don’t go by the deadlines,” she’d say. “I go by the lifelines.” Mama’s Gun, which she produced herself, was harder and funkier than Baduizm and yielded another hit, “Bag Lady,” an advice song to women about cutting loose their emotional pain (“Girl, I know sometimes it’s hard and we can’t let go . . . Let it go”). By then Badu had tired of the gele and surprised audiences on tour with a shaved head. Her fourth album, Worldwide Underground, took another three years, much of it written on the road, improvised during sound checks and performances. The result was weirder than anything she’d done before, with riffs and syllables repeating for minutes at a time, more Laurie Anderson than Lauryn Hill. The album had nothing on it approaching a hit, and on the cover Badu wore a giant Afro, Angela Davis—style. Next to her head were the words “Neo-Soul Is Dead.”

After thirty minutes the class was done, and everyone stood around sweating and smiling. Badu and the kids got together for a group photo; then she, with Weiss at her side, gave a brief speech. “You guys,” she said, “I was not the best dancer—”

“But,” Weiss interrupted, “she had more than that. She had heart, which is what every artist has to have.” Everyone clapped. Someone in the group began singing “Tyrone” and others joined in: “I think you better call Tyrone. And tell him, come on, help you get your shit . . .”

Everyone looked at one another and laughed; they knew they would get a pass because Badu had written it. By now there were two dozen other students and teachers in the room watching. Someone called, “Sing!” and someone else added, “‘Tyrone’!” Badu laughed, sat down, and made everyone else sit in front of her. “I’m gonna sing,” she said, “but not ‘Tyrone.’” She started snapping her fingers slowly, and everyone followed. Then she began singing softly, and again they followed: “Ohh, oh-ohh, oh-ohh, oh-ohh, oh-oh-oh-ohh.” It was “Bag Lady,” and the students knew every word. Badu was completely relaxed, doing what she loves to do more than anything: perform.

Afterward, she hugged teachers and talked with students, many of whom took her picture with their cell phones. She said about her alma mater, “I still go there when I want to think.” Then she added with a laugh, “Before I went to New York, I went to Pegasus [a campus sculpture of the school mascot] to ask permission: ‘Oh, Great One.’” A young, dark-skinned girl approached her. “I heard you’re from South Dallas,” she said. Badu smiled and nodded. “That’s my hood. I just want to look at you,” the girl continued, talking fast. “You’re a superstar. Maybe I can take a picture with you?” Someone said, “She can sing too,” and after a little prompting from her friends, the girl asked Badu if it was okay if she sang something. Sure, said Badu. The girl shut her eyes and opened her mouth; her voice was big and powerful, from the church. “I keep on falling in and out of looooooove”—here she employed the gospel melisma that is inescapable in R&B and pop music these days—“with you. Sometimes—” and she stopped abruptly. “Thank you so much for listening,” she chattered. “So, like, when you see me in a few years—I want fame just like yours. I don’t know if you can hear it in my voice . . .” Badu kept a smile on her face, and the girl eventually stopped and ran off with her friends, whooping.

“Now that,” Denise said, “was a first.”

“This used to be one of the most beautiful neighborhoods ever,” Badu said as we drove along Pennsylvania Avenue in South Dallas. “Families were active, lawns were beautiful, trees looked nice, people put up Christmas lights at Christmastime. It was a neighborhood. Now I feel like I’m in New Orleans after Katrina.” We turned onto some of the cross streets. Many houses were abandoned, while most just looked worn-out. Plenty had their windows boarded up. Yards were muddy, and stray dogs walked slowly down the street. “South Dallas dogs are so slow,” said Badu with a chuckle. We drove some more. “South Dallas used to be called Sunny South Dallas,” Badu said, sighing. “It’s not called that anymore.”

It was the usual suspects, she said: “Time, drugs, lack of money, lack of education, lack of willpower.” So how, then, did you get out of here? “My family. I was raised by strong women. My mother made me this way.” Badu’s late father, William “Toosie” Wright, spent most of her life in prison, so she and her sister and brother were raised by her mother, Kolleen, while spending a lot of time with her two grandmothers, Thelma Gipson and Viola Wilson. “I had a progressive-thinking family. My mother had a lot of friends who would introduce us to things, give us tickets to go places. My mother gave me my sense of style and wit and sophistication, but she also wanted us to stay in South Dallas—she wanted us to know who we are. I got my manners and morality from Thelma and my spirituality from Viola. There was also my godmother, Gwen Hargrove [Roy’s mother], who was my mom’s best friend. She ran the MLK rec center and gave me my sense of art.”

Badu spent a lot of her time at the center, dancing, acting, learning about African culture. She picked up her mother’s love of sixties soul like Motown and seventies soul like Earth, Wind & Fire—funky yet mystical, sexy as well as socially responsible. She began writing songs at six on a family piano; soon she was rapping too. “My nickname from elementary school was Apples,” she told me, “because my cheeks were so big they said I squirreled away apples in there. My rap name was Apples.”

We passed the rec center and St. Philip’s, an all-black school where Seven is enrolled. “I wanted him to know his heritage,” Badu said. We passed the elementary school her mother went to, then a nursing home. “My great-grandfather was there. I’d walk there every day to visit him.” We drove by two older men sitting on a front porch, and Badu honked; they looked and waved. We drove by the house she was raised in, where Thelma lives now.

Badu lives in a big house on White Rock Lake, but she spends a lot of time on the streets where she grew up. She teaches math, science, and art at the Africa-Care Academy, where both her children have gone, and talks about starting her own fine-arts school in the same neighborhood. She’s done things like cut the ribbon for the opening of a new playground at a public housing development and sing a song she wrote for the opening of the Freedman’s Memorial Cemetery. “Make some noise for our ancestors,” she said to the crowd, and that could be her call to arms in the community. In 2003 she started an umbrella organization called Beautiful Love Incorporated Non-profit Development (BLIND), which raises money, holds coat drives, and organizes seminars at high schools to talk about things like AIDS and drugs.

Her biggest project is right in the middle of the neighborhood, on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, near the intersection of Interstate 45 and U.S. 175: the Forest Theater, a giant old movie house from the late forties. Badu used to see Pam Grier and Bruce Lee movies there, and in 2003 she began leasing it and fixing it up. “This theater is really the only thing left in this neighborhood,” she said. She renamed it the Black Forest Theater and has played benefits there, while other artists, such as Prince, George Clinton, and Snoop Dogg, have also performed. Badu allows people in the community to use the theater free for church services, quinceañeras, and dance classes, and it is also the headquarters for BLIND.

We walked around the inside—the huge main room with high ceilings, the black-and-white-checkered floor, the winding art-deco lobby—then went out front. Giant Afro combs with black fists as handles were painted on the doors. Words on the marquee read “Brothers fighting over who got the fattest chains like slaves on a slave ship.” A Muslim man in a coat and tie hawked issues of The Final Call to drivers waiting at the light, and Badu stopped and chatted. A bus driver opened his door and yelled, “Hey, Erykah!” She yelled back, “What’s up?” A steady stream of cars honked, and she waved.

Next door was a strip of six ragged stores including a barbershop that’d been there since 1961; Elaine’s Kitchen, a Jamaican restaurant; Sankofa Arts Kafé, which used to be the Green Parrot, a club run by Badu’s grandfather and his brothers; and Dread-N-Irie’s, a men’s clothing shop run by a Nigerian man named Sonny Otutu, who used to manage a club in Deep Ellum that Badu freestyled at in the early nineties. Badu would like to buy and renovate the whole lot, theater and stores, but right now she can’t afford it. “Maybe we can use it to generate some kind of rebirth,” she said. “So people can see who we are.”

We drove to St. Philip’s to pick up Seven—who wore the school uniform of blue slacks and white shirt and sported a mohawk—and drove back to Badu’s house, where she took me upstairs to her home studio to play me some songs she’d been working on. She has a large mixing board, a rack of effects, some keyboards, a guitar, and a very expensive microphone specially made for her, as she puts it, “nasally” voice. She records everything on hard drives with computer programs such as Pro Tools and GarageBand, sometimes with an engineer, sometimes on her own. She might use what she does there as a blueprint, or it might make it to the final album. In a house of artistic playthings, this is her sandbox.

Badu sat with a Mac on her lap and called up a menu of song files. “I’m still listening to the music on a lot of these, trying to come up with the words,” she said. “When I work on a vocal, I put the drums, bass, and keyboards on one track, then do as many vocal tracks as I need to come up with the lyrical idea.” She clicked on a song she had been working on the night before, and a snaky, jazzy guitar riff over bass and drums came out of the speakers, her voice hovering over it in a melody full of words you would find in the dictionary and syllables you might not. “The music is ninety percent of the song. Lyrics are five percent and melody is five percent—they live in the music. After I do the music, I find the melody and use it to create a phrase.”

“Do you ever hear the words first?” I asked.

“That,” she insisted, “would be poetry. I’ll sing a phrase; there are lots of things floating around unclaimed in my brain. But there are periods where nothing comes to me, months and months. If it’s not coming to me, that means I have to go out and find it—maybe in a painting, maybe within certain sound frequencies. I’ve been reading a lot about Quetzalcoatl and Nikola Tesla; maybe that’ll make its way into these songs.”

Once again, Badu is taking her time; the new album was supposed to come out in 2005, then 2006, and now later this year. In fact, though, she’s already completed one record—and discarded it. “It was a theme album about Loretta Brown, this fabulous space chick, a young woman from 2060, but in her mind she lives in 2040. Twenty-sixty is like the 1960’s, but she dresses in the fashion of the 1940’s. I recorded fifteen songs, did a photo shoot, made a video, but then changed my mind. I didn’t feel it anymore.”

She started over and now has, by her count, about eighty pieces. Some are complete, and some are just riffs or bass and drum loops. She has culled these down by half, splitting them into two batches for possible albums. One she recorded with an actual band, Funk Sway, which includes Doyle Bramhall II and Wendy and Lisa from Prince’s old group, the Revolution. The other album has, in her words, “more of a street edge.” She played me a song from it with dramatic, ascending synthesizer strings that sounded like something from Foxy Brown; on another she sang, “To be a dancer, don’t nobody know,” in a voice that sounded like Diana Ross. “I’ll put horns on that tomorrow night. I think it needs sax, trumpet, and trombone.” I told her that what I was hearing didn’t sound much like anything she’d done before. “I don’t know,” she answered. She clicked on a song called “Black Girl Lips,” a slow, careening, singsongy tune with Badu playing rudimentary guitar and singing, “Everybody wants some big fat black-girl lips.” She’d gotten the idea, she said, a few nights earlier after she and her mother had watched a Dateline episode about plastic surgery. “I thought, ‘Everybody wants some big fat black-girl lips, but they don’t want to hear nothing we have to say.’”

I asked if she worried that she was starting too many songs without finishing enough. “There’s a method,” she insisted. “It will be finished when it’s finished. That’s pretty mean to the record label, but what can I do? I want to tell a cohesive story, show what I’ve seen, how my imagination has developed between Worldwide Underground and now.”

I told her about a comparison I found irresistible: Beyoncé versus Badu. Houston versus Dallas. Heavily marketed pop star versus relentlessly free spirit. Badu deflected any invitation to dis Beyoncé. But why not, I asked, at least aim to write a huge radio hit that would pay for everything: the theater, the fine-arts school, a new house for your mother? I even suggested a title: “Groovylicious.” Badu ignored me. “I don’t listen to the radio,” she said. “I should, to see what’s going on. Maybe someday I’ll be smart enough to figure it all out—how to get this money. Right now I don’t want to. I believe in what I’m doing so much I don’t want to compromise anything. I don’t feel like I have to right now. I know what you’re saying—it would make sense. I mean, I have a brand. If I really worked hard, I could make fifty million dollars by the end of next year. But I want to do it the right way. I always see my grandmothers’ faces. They wouldn’t be happy if I wasn’t happy.”

It was dinnertime and getting late, but Badu burned me a couple of CDs’ worth of music she’d been listening to lately, each one full of obscure seventies soul and funk by musicians like the Sylvers, Parliament, and Gary Bartz, whose “Music Is My Sanctuary,” from 1977, with its unpredictable jazz-soul sound and mystical lyrics, is clearly a great-uncle of some of Badu’s own creations. We went downstairs, and Puma, who had been playing with Ysheka, squealed when she saw her mother and ran into her arms. It was almost time for Seven’s tae kwon do lesson just around the corner, and Badu was set to take him there. They would ride on skateboards. She would come back to the studio later that night, write and demo three new songs, and quit at about five in the morning.