Charles Stagg walked into the woods and decided to build something. There was a spot he liked in the pine forest about a quarter mile behind his parents’ house in the small Beaumont suburb of Vidor. Stagg chopped down the trees to make a field, then pulled bricks out of a landfill and hauled them out there, blazing a trail through shrubs and weeds along the way. Soon he was spending all day in the newly cleared patch, mixing concrete and laying the bricks. He only stopped when his mother came out to bring him meals.

A cluster of concrete buildings slowly rose up on the site, and Stagg began living in them full-time. The entryway was a room he called “The Church of the Swirl,” a concrete foyer topped-off with a narrow, swirling chimney that looked at home in between the pines. Beyond that was a small courtyard and then the centerpiece, a circular studio capped by a twenty-four-foot high hexagonal dome. There was a fireplace inside the studio along with a concrete chair and table that rose out of the floor. In almost all of these rooms—foyer and studio, but also bedroom, storage space, doghouse, even sauna—Stagg embedded glass bottles in the walls. When sunlight filtered through the trees and caught the glass, it produced gorgeous patterns of green, red, blue, and brown, but they were also functional. “The bottles collect warm air from the daylight and retain it through the night,” Stagg told Metropolitan Beaumont in 2004. “It is a little too hot in the summer but it is pretty comfortable to sleep here in the winter. I intend to have my ashes here one day.”

But why did he do all of this? Because Stagg, perhaps, knew something that most wouldn’t understand until years later—his home would become his masterpiece, one that wouldn’t be finished when he died in 2012.

Stagg’s interest in art started on this same piece of land in the 1940s, though he had a circuitous path back to it. While his father, Etienne, raised hogs, Stagg would go down to a riverbank and draw crude sketches, mostly of fish, in the sand with a pole. In high school he wanted to build things. He thought about sculpture, but the bulk of his exposure to the art was through magazines that fell into his hands from time to time. His first job after graduation was at Bethlehem Steel, which he told KVLU in 2009 was “a rude awakening to the real world,” one in which he toiled in 115-degree heat and tried to keep sweat from dripping in his eyes. It was not the type of building he had dreamt about, so he enlisted in the Army, where he was an engineer in the 23rd Battalion and a baritone in the 3rd Infantry Division Choir serving in Germany. In 1960, he returned home and married his first wife, Cecile, the following year. Looking back on Germany, his fondest memories were of the architecture he’d seen.

Stagg and Cecile divorced five years later. At the beginning of a new marriage, Stagg quit his job and went to art school. He started out at McLennan Community College in Waco, then transferred to Baylor. In 1974, he got an MFA from the Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia, where he studied with Italo Scanga, a veteran artist interested in using found objects. For the next few years, Stagg bounced around from place to place. He went back to Beaumont, then Washington, New York, and Philadelphia. In 1981 he returned to Vidor to care for his aging parents, and it was then that he started working on his home and pièce de résistance.

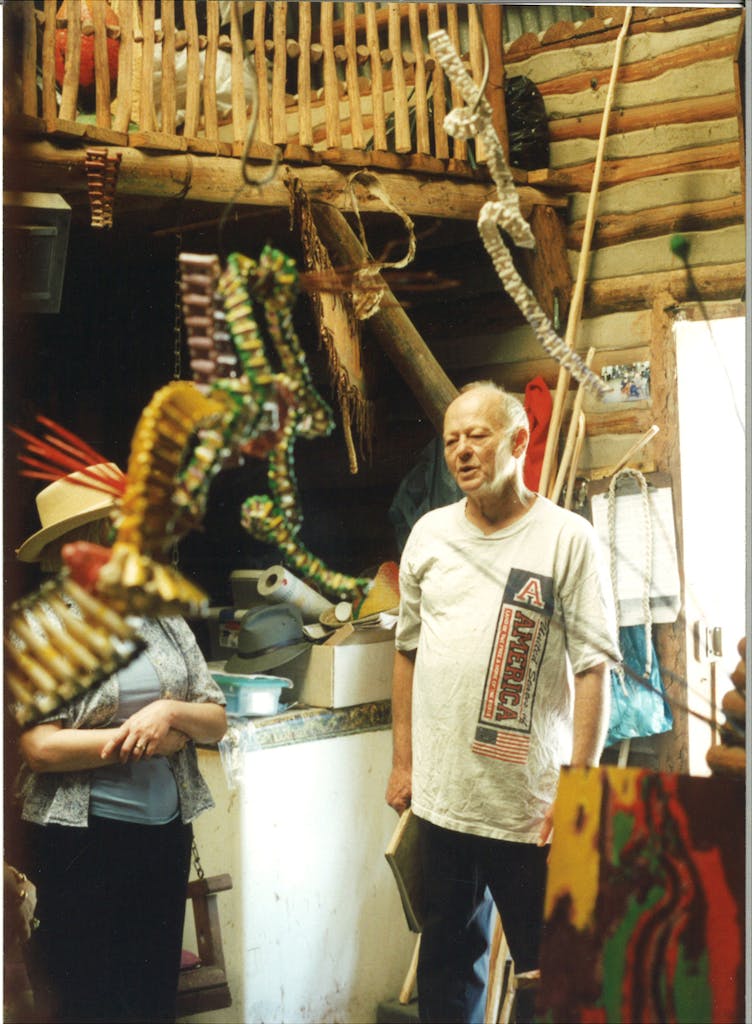

Stagg’s daughter Michele Woods, the only child he and Cecile had, inherited the property. Recently, I met Woods and her son, Kevin, for a tour of the site. Woods wasn’t sure if she wanted to go, but Kevin reassured her. “It can be a lot, going out there,” he said. “Seems like every time we do, things are a little more broken down than the last time.” But the more Kevin told me about Stagg’s work, the more Woods kept asking him to report back to her about specific pieces. Eventually, she decided to just go see for herself. When we reached the buildings, their faces fell. A mountain of broken bottles stood on the ground in front of his studio. Weeds and vines were crawling up the sides of most of the walls. Graffiti scribbles and initials adorned the concrete surrounding the bedroom and courtyard. At the entrance to the compound someone had spray-painted a red “X” over a “Beware of Dog” plaque Stagg had placed there back when his canine companion, Tsuze, called the place home.

Not all the changes at the site were for the worse, though. At one point, Woods ran her hand over a concrete wall spotted with yellow lichens. “He would have loved this,” she said. Later, we walked into Stagg’s bedroom, which was lit up by a wall of floor-to-ceiling green bottles. She noticed a bird’s nest peeking out between the necks of what might have been someone’s Sprite.

Woods was only two years old when Stagg and her mother divorced. From eight-years-old and on, she was raised by her mother and stepfather in Louisiana. But Stagg and Cecile remained lifelong friends, and Woods stayed in touch with her father. In the car on our way back from the cottages, Woods held in her hand a small piece Stagg built for her—a sculpture made from tiny pieces of wood painted pink and stacked in a helix. Starting in the late eighties he had made many similar objects by stripping the bark from the pine trees near his home, then stacking dowels at right angles to create towers. Some reached the top of his twenty-four-foot studio and resembled massive strands of DNA. “I think of them as life forms,” Charles told Beaumont Enterprise in 2005. “The shapes of the pieces are life dispersions.”

“He talked a lot about his art,” Woods says as she laughs, “But I didn’t pay attention.” As a child she often found his sermons to be too much. “It wasn’t that I didn’t listen to him,” she says, “but he would pump that information and I didn’t really know how to process it. I really couldn’t understand him. And there was not that personal interaction of ‘How was your day? What’s going on in your life?’ You know, that kind of stuff. I think as I got older that’s kind of what separated us.”

But despite that separation, Woods and her son have been working to protect his buildings. A few years ago, they considered forming a team of Stagg’s friends to clear space for a fence around the multi-acre property, but the cost of installing it was too much. Even if they had been able to secure funds, says Woods, there’s no guarantee that a fence would have kept anyone out of such a spot, which was buried deep in the woods away from roads and neighbors. The most promising solution might be to rely on an outside organization that specializes in these types of projects. They’ve have been in touch with the Kohler Foundation, a nonprofit that supports art preservation, but nothing has come of it yet.

Unlike his mother, Kevin was a little more curious about his grandfather’s projects during his childhood. When he asked Stagg to explain his pieces though, the artist refused. “He’d say, ‘It’s not a very good joke if I have to tell you the punchline.’” The response frustrated Woods. “I want to make relationships,” she says. “And so to make the relationship, the art should bring the people together and not separate them.”

“He wanted to build the relationship through the art,” Kevin says.

“And I wanted to build the relationship through the communication,” she replies.

“Right,” Kevin says. “Using the art as a tool. It’s a different way of trying to connect people.”

At Stagg’s funeral, Kevin played a hand drum and his sister sang. The audience was shocked—they had no idea the artist had grandchildren or even a daughter. Now, driving away from the compound, Woods thinks back on the time her father spent building. “I always felt like that was kind of my sibling out there,” she says. “And it was his favorite child.”

Towards the end of the summer in 2006, thirty years after Stagg had started working on the compound, it caught on fire. All of the pine sculptures in his studio, plus works he had collected from other artists, went up in flames. By this time, despite his seclusion on the compound, Stagg had fans. Students from Lamar University had been coming out to help him build for years, and artists, curators, and friends stopped by frequently to donate items that might become part of the walls. Sometimes people just showed up, which was fine with Stagg, he told the Beaumont Enterprise, “as long as they don’t come after dark.” In the aftermath of the fire, a number of these people reached out to offer help. When they did, Stagg was surprised. “I’m starting to realize how many people are involved in what I’m doing out here,” he told the Enterprise. “I’ve lived alone for so long I didn’t have a good barometer.”

Investigators never determined a cause for the fire, even though Stagg was convinced it was arson. Still, when the Enterprise reporter asked him how he was coping, he caught her off guard. “My emphasis was not on building something of permanence,” he said. “But something I could learn from. The only thing I feel bad about is losing my collection of other people’s work. My collection was built to be gone—and it is.”

Some pieces of the collection did survive. At the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, a few of Stagg’s life-form sculptures tower above your head when you enter the lobby, winding their way from up to the ceiling from a platform above the door. Lynn Castle, the executive director of the museum, remembers watching Charles in the summer of 1989 when he built an installation of sculptures in that same lobby. For three weeks he climbed around scaffolding, shirtless and barefoot at an altitude where air conditioning can’t help you. When he finished, she said, it was one of the best installations she had ever hosted.

Castle describes Stagg as a process artist, and though he never used the term himself, it’s helpful in distinguishing his style of building from that of an architect or construction worker. Typically, if someone wanted to build a house, they would probably picture it in their head first as a small, solid rectangle, then pick some material that could be used to achieve that form, like metal and concrete. When Stagg built his sculptures, however, he simply he cut pine limbs and started stacking. He didn’t hold onto any images of the final product. Instead, he let the characteristics of each twig determine how the next one would fit. “Each sculpture acts independently almost as if it has its own personality,” wrote Castle in her description of Stagg’s installation. The artist’s job was to let these personalities come alive, twisting and bending as they did. He employed the same philosophy with his ever-evolving domicile, and that’s where things got messy. “I’m the kind who would build a house and then pour a slab under it,” he told the Enterprise in 2007. “I engineer failure just to see what it takes to make it fail.” Woods and Kevin remember concrete walls collapsing before Charles reworked them to stand upright. But for Stagg, a failed creation could be just successful as a completed tower or a room with a door. That’s because his work was never about the products, but rather the process by which they emerged. As long as he got up every day and worked, he had done his job.

But this meant that there was little time for anything but work. During the decades that he spent on the compound, Stagg rarely took the time to step back and admire. In 2004, just before the fire when Stagg’s home was at its peak, the Metropolitan Beaumont sent out a writer to report on it. “These pieces are never really finished,” he said as they walked through the structures. “You can add on to them or take pieces away.” The writer saw Stagg’s bedroom, with his mattress lit up green by the wall of glass bottles, his studio full of helixes and other artists’ work, his doghouse where more than one animal kept him company over the years, and a sauna he built to relax in after working. “From the moment guests arrive and see Stagg in his natural environment,” she wrote, “it is apparent that his creations cannot be separated from the activities and objects of his life.”

“He was driven, you know?” says Woods. “But you need to balance that. That was a real lesson in itself for me and that made me want to smother my children.” It’s a good thing that she did. Because now, four years since Stagg passed away, it’s up to her and her own child to look after what he built.