“Let’s pretend that a certain magazine writer believes that this season is UT’s best chance to win the national championship in more than thirty years,” a certain magazine writer says to Mack Brown. “How would you answer that?”

“First, I’d say that the writer probably doesn’t know enough about football,” Brown replies, with all the humor of an undertaker. “Since I don’t know how good the team is going to be, I know that no one outside of this business can know. I also know that’s the kind of hype that sells magazines.” The coach and the writer consider each other for a moment, then a slight grin creeps across Brown’s face. “Second, I’d say that we’ve got more experienced depth than we’ve ever had since I’ve been here.”

For the head coach of the University of Texas football team, winning the national championship is a bit like studying the sun. It’s always burning down on you, but you can’t look directly at it. During Brown’s hiring process, in December 1997, UT regent Tom Hicks said he was looking for the guy who could bring home the national title. That frankness makes sense at a university that began paying its head football coach more than its president way back in 1937, and the search committee unanimously agreed that Brown was the man to do it.

After four seasons in Austin, he has rewarded the school by winning 38 games and losing only 13. That marks the program’s most productive stretch since the period between 1969 and 1972, which just happens to include the school’s last two national championship teams. Brown is coming off a season in which the Longhorns won eleven games and finished with a top-five ranking for the first time since 1983. He enjoyed another recruiting period in which he won his second unofficial national recruiting title, and when the preseason polls are announced, UT is sure to be in the top three. ESPN’s Ron Franklin—a former broadcaster of Longhorns games—picked the team to be number one.

But Brown is at the point in his career where being known as one of the best coaches in the country is less important than proving that he is the best. Fairly or not, at the University of Texas, you are not thanked for winning eleven games. You are criticized for losing the two that kept you out of the national championship. “Some of the alumni and former players want to win so bad that it’s a little unfair,” says James Street, who was the starting quarterback for the Longhorns’ 1969 national championship team. “But Mack knew that when he came in. Nine wins a season just isn’t going to cut it.”

Well, those alumni and former players should take heart. When the Longhorns hit the field on August 31 against the University of North Texas to open the season, Brown will be coaching the team that has the best shot at winning it all in 2002. “I think Mack has the chance to have the best team that he’s had,” says Darrell Royal, who coached UT to its three national titles, in 1963, 1969, and 1970. “It’s not a done deal, but we’re a contender. The program is up, and we’re jellyrolling.” Translation? This could be the year. Here are five reasons why.

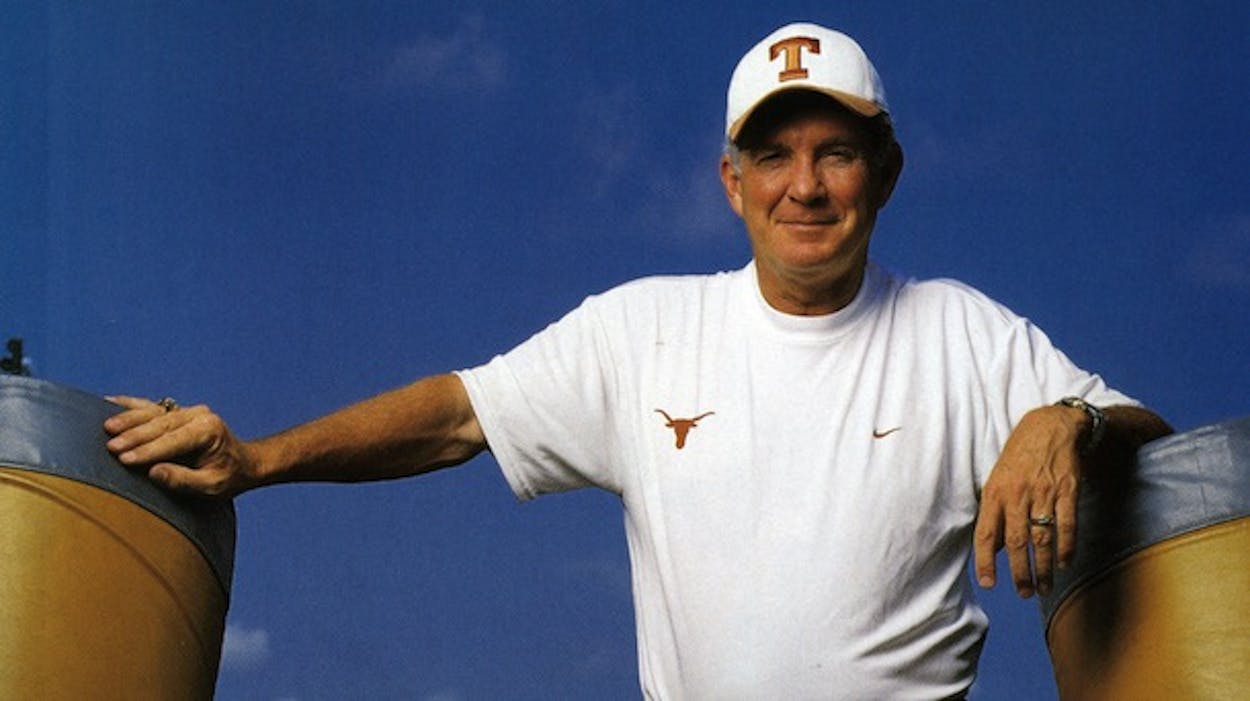

The Coach

ON A STEAMY JUNE MORNING, Brown is cooling off in his office overlooking the south end zone of the Darrell K. Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium. The room is large enough to seat 75 of his closest friends, and with its dark-wood blinds and paneling, it would assume the air of Vito Corleone’s office if it weren’t for the decor: Longhorn heads and Longhorn sculptures and Longhorn-hide pillows and Longhorn-hide chairs and Longhorn-hide rugs and burnt-orange leather couches. The fifty-year-old has just returned from running his football camp for elementary through high school kids, his cheeks are flush, and he’s wearing the distinctive smell of sweat. His graying hair, which is normally parted from left to right, is running in the opposite direction. The more he tries to smooth it with his hand, the more unruly it becomes.

“The national championship is the goal for every program in America at this level, so I’m not ashamed for us to talk about it,” he says. “We talk about it in the off-season, but we talk about it as an end-of-season goal. We do not mention the national championship with our team after the season starts.” As for winning it, he takes the pragmatic approach. “Our goal is to win the opener, and that’s the hardest game of the year because you haven’t played,” he says. “Then our goal is to win the Big Twelve South Championship. Then our goal is to win the Big Twelve Championship. Then our goal is to win a bowl game. If you win the Big Twelve and you win your bowl game, the national championship takes care of itself. So what we’ve said to our players is, ’Don’t be afraid to talk about it, but understand that you’ve got a lot of steps on that ladder.’”

Brown has been climbing that ladder for most of his life. He grew up in Cookeville, Tennessee, where his grandfather, Eddie “Jelly” Watson, was one of the most successful high school football coaches in the state. Brown played baseball, basketball, and football at Putnam County High School, and he was a good enough running back to have been recruited by Paul “Bear” Bryant at Alabama. But he chose to go to Vanderbilt, then transferred to Florida State, where he earned two letters. He moved his way up the coaches’ pecking order at various programs, working as a receivers coach, a quarterback coach, and an offensive coordinator. He took his first head coaching job, at Appalachian State, at the age of 32, guided the team to its first winning season in four years, and promptly left to become Barry Switzer’s offensive coordinator at Oklahoma. Once again he left after just one year. He returned to head coaching at Tulane University, in New Orleans, but shortly after he started, in the spring of 1985, a scandal involving the basketball team devastated the athletics department. That winter, a group of consultants evaluated the program’s situation, and Royal happened to be a member of that committee. According to Brown, Royal gave him some candid advice about the school: “I’d get the hell out of here as fast as I could because you’ve got no chance,” he said. “And I would go to a university that has ’the’ in front of it, because that’s the only way you’re going to make it.”

The University of North Carolina came calling not long afterward, and Brown gained national attention for turning around the struggling program. He went 1-10 in his first season, 1988, and finished 10-1 with a final ranking of sixth in the country in his last, 1997. That same year, UT football went into a tailspin. Head coach John Mackovic led the Horns to a record of 4-7, the worst finish for UT since 1988. The Mack Brown era began in Austin that December, and he immediately did something that Mackovic had never bothered to do: reach out to prominent former players and, most important, Darrell Royal. His goal was to reinvigorate the program by recalling its glory years and positioning himself as the heir to Royal’s throne. “When he did that, he brought in more than Coach Royal,” says Street. “He also brought in all of the supporters, all of the alumni. He brought back the feelings of a special era.” Brown, though, was not content just to revel in UT’s traditions. He wasn’t afraid to say what he thought was wrong with the program, including a lack of vision, a failure to promote the team, and inconsistent recruiting. He even addressed the touchiest of all subjects, saying that the school wasn’t working hard enough to bring inner-city athletes to the school. Street was impressed. “After I first met him, at a breakfast, I called a couple of guys and said, ’If I were starting a business, this is who I’d hire,’” he recalls. “He’s a marketer, a coach, a politician, and a CEO. He’s all of them. When he speaks to groups, he doesn’t miss a constituency. He hits the men’s sports, the women’s sports, the former athletes, the alumni.”

Despite Brown’s success, he has struggled with one thing: winning the games that matter most. After eighteen seasons as a head coach, he has never won a conference title. That inability to win the big one has hounded him since his days at North Carolina, where, in six tries, he never once came within even a touchdown of beating powerhouse Florida State. During his tenure at UT he is 7-10 against top 25 teams and 3-7 against top ten teams. In 2000, when the Horns were ranked eleventh, he lost to number ten (and eventual national champion) Oklahoma 63-14. That kind of blowout can happen at schools like North Texas, but it should never happen with a program as rich as UT’s. Last year, when Texas was ranked fifth, Brown lost to number three Oklahoma 14-3. The Horns suffered from a conservative game plan that netted just 27 yards rushing.

So what’s different about this year? For one, Brown has always believed—until now—that the preseason rankings of the Horns in previous years were based more on reputation than talent. In 2000 he started two freshmen wide receivers, and last year he started a freshman running back in seven games. “We weren’t as good as the expectations, and as a coach you know that,” he says. This year marks his first team without any players who were recruited by Mackovic, and the depth chart is loaded with playmakers. The team should also be more stable—and more focused—because it no longer has to deal with the distraction of a quarterback controversy. Last year Brown picked Chris Simms as the starter over fan-favorite Major Applewhite, a decision that caused more debate than Florida’s election returns. Though Brown insists that the issue didn’t create any problems for the team, it certainly led the media and his critics to question his coaching once again, complaints that he brushes aside. “We’ve gotten too much credit in recruiting and not enough in coaching,” he says. “Recruits are not going to come here unless they’re going to be well coached, and gosh, we’ve won a lot of football games over the past couple of years. People get labeled for stuff, and we’re the ’good recruiting bunch.’ But if you’re fifth in the country, you must have coached someone decently.”

Darrell Royal is a bit more direct in his assessment of Brown’s ability. “What’s the bottom line?” he asks. “Three words: Mack’s good.” He then thinks intently for a moment. “Or is it two words with the apostrophe? Well, it doesn’t matter. Mack’s good.”

The Quarterback

MAKE NO MISTAKE ABOUT IT: Chris Simms can win the national championship. He has the talent, the work ethic, and the brains to make it happen. Most important, after last season he now has the experience. That doesn’t mean it will be easy for him to forget December 1, 2001, a date when the stars in the national championship universe seemed to be smiling on the Burnt Orange. Many fans had given up hope for a national title at the Cotton Bowl in Dallas two months earlier, when the Longhorns lost to Oklahoma. But OU lost twice after that, first to Nebraska, then to intrastate cream puff Oklahoma State. UT unexpectedly found itself back in the Metroplex to play in the Big XII Championship against Colorado, a team the Longhorns had dismantled earlier in the year. When the players roared onto the field at Texas Stadium, they also unexpectedly found themselves playing for a place in the Rose Bowl, the site of the national championship game. Tennessee had tripped up undefeated Florida just moments before, and suddenly UT’s loss to Oklahoma was irrelevant.

The implosion began about eleven minutes into the game. Texas led 7-0 and was driving for a second score when Simms, throwing on first down, took a three-step drop and telegraphed his throw to tight end Bo Scaife. Interception number one, followed three plays later by Colorado touchdown number one. During Texas’ first drive of the second quarter, Simms looked right, then threw left as Roy Williams broke toward the middle. But Simms didn’t pick up a linebacker lurking in zone coverage. Interception number two. Colorado touchdown number two. A few minutes later, Simms ran a play-action pass, and the pressure forced him to scramble to his left. He failed to tuck the ball away, and Colorado knocked it loose and fell on it. Another Simms turnover. Another Colorado touchdown. On Texas’ next drive, a linebacker blitzed up the middle. Simms sidestepped the rush only to throw a bullet into double coverage. Interception number three. Colorado touchdown number four. With the score Colorado 29, Texas 10, Simms would last only one more play before clutching the ring finger on his throwing hand and making his way to the sidelines. Colorado knocked him out with 2:03 left in the first half.

Texas fans would add insult to injury. It didn’t matter that Simms had passed for a school-record 22 touchdowns during the season and won ten games, the most for Texas since 1995. It only mattered that he had ruined a shot at the national title. The crowd booed Simms unmercifully, and after the game someone posted his cell phone number on the Internet. More than fifty irate fans were all too happy to call and offer their opinion of his performance. And, of course, the quarterback controversy reignited. Applewhite came in, fired up the Horns, and passed for 2 touchdowns and 240 yards. Texas still lost 39-37, but Applewhite earned the starting job in the Culligan Holiday Bowl against Washington, and Simms took a seat on the bench. Though Applewhite himself started shakily in the bowl game—throwing three interceptions in the first half—he rallied UT to a masterful, come-from-behind win 47-43, passing for 473 yards and 4 touchdowns, both school records for a bowl game.

Now the biggest question mark for 2002 is whether or not Simms has the confidence to bounce back. The answer is yes. His coaches praise the work that he did during spring drills: mastering the offense, honing his throwing technique, and working on spotting an open receiver. “The spring was a good chance for me to start over since the season didn’t end quite the way I wanted it to,” he says. “It was a letdown to have such a great year and have a chance to go to the national championship and not come through. But I wanted to establish myself as the leader of the offense.”

Simms understands the criticism, but that doesn’t mean he thinks it’s fair. “I know that certain things are going to happen when you’re the quarterback of a major program,” he says. “At the same time, I was a little disappointed with some of the fans. You’ve got to put yourself in my shoes. I picked this university because I really loved it, and here I am busting my butt every day, and you know, I basically had a bad quarter, and they boo you. It hurts you. It really does.” Simms will certainly have a mental hurdle to get over when he takes the field this year, but the disappointments from the 2001 season will only make him a better quarterback: The experience taught him how to deal with the pressure.

Last year the expectations for Simms were unrealistic. Before the 2001 season, he made the cover of ESPN The Magazine and The Sporting News, and he was touted as a Heisman trophy candidate after starting just seven games in two years. This time around he didn’t even make the first-team quarterback for all Texas schools in Dave Campbell’s 2002 Texas Football. (Kliff Kingsbury of Texas Tech got the nod instead.) As if to try to encourage a lower profile, he has even changed his jersey number: During his senior year he’ll be wearing number two instead of number one. Even better, he doesn’t have to compete with Major Applewhite, the man who holds UT’s career records for completions, attempts, yardage, and touchdowns. The offense belongs to Simms.

As for his physical skills, he has struggled at times to read defenses or master the finer points of his position, such as looking at all of his receivers instead of staring at the one he wants to throw to. Royal scoffs at that, saying that Simms is as talented as anyone in the country, even if he did make some poor decisions. “Why are people saying he doesn’t know how to pick up a second or third receiver?” asks Royal. “Those are the folks who couldn’t even draw up a second or third receiver route for you.” Another vote of confidence comes from James Street. He believes that Simms has all of the tools to take the team to the next level. “Has he won the big game yet? No. Can he get the job done? Yes,” he says. “But I don’t give a damn who you are, you’ve got to get lucky. He’s on the right track to win a national title. His career at Texas hasn’t been defined yet.” And Simms is more than eager to address the most stinging criticism of him: that it takes more than good looks to win it all. Does he think he can get the job done? “There is no doubt in my mind,” says Simms. “I just have to go out and prove my critics wrong.”

The Talent

UT CAN COUNT ITSELF LUCKY that its biggest worry is the performance of a senior quarterback who could be the best player in the country. Mack Brown’s team will feature the most explosive offense in the Big XII, boasting more weapons than a Harris County gun show. Last year UT led the Big XII in points per game (39.2), and Simms will guide an offense that returns eight starters. Texas has the deepest corps of receivers in the country, featuring juniors Roy Williams and B.J. Johnson, who have both started twenty straight games. In 2001 Williams caught 67 passes, the second-best total in UT history, and he’s on track to break UT’s all-time record for receptions. He did all of that last year while playing with a nagging ankle injury, and he’s happy to show off the one-inch scar that was a result of a successful off-season surgery. He knows that he will be even better this time around. “I’m not saying I’m the best receiver in the country,” he says. “I know there’s somebody out there who’s better than me, because that’s what my mom says.” The ground game is just as strong, with heralded sophomore Cedric Benson returning at halfback and senior Matt Trissel at fullback. Benson started just seven games last year but rushed for 1,053 yards, a UT freshman record. Aside from injury, the only thing that stopped him was the Midland police department, which arrested the hometown hero in a friend’s apartment in late April and charged him with possession of marijuana that was found on the premises. The charge was later dropped as a result of insufficient evidence, and Benson passed a drug test to help clear his name. With a season of college ball under his belt (and some much-needed work on his pass blocking), he looks to be an even more dominating force in 2002 and could be the difference against great defensive teams like Oklahoma and Nebraska, when he should be getting 25 to 30 carries a game.

The other side of the ball is almost as strong. Last year the defense ranked number one in the country, and though it returns only five starters, it will be one of the best again. The defensive line includes one of the best ends in college football, senior Cory Redding, and he’s confident about leading the charge. “This year we’ll refuse to lose,” says Redding. “We will keep the dream and keep the hunger, and we’ll make it.” Despite the loss of cornerback Quentin Jammer, who was the fifth pick in this year’s NFL draft, the secondary is sharp, with junior Nathan Vasher switching from safety to corner to help fill that spot. Last year Vasher tied the UT record for the most interceptions in a season with seven.

Depth—an inexhaustible supply of talent to protect against injuries—is one of the most important aspects of the program, and it is the direct result of Brown’s passion and talent for recruiting. Unlike Mackovic, whose sometimes-frosty personality could turn off recruits, Brown bursts with enthusiasm.

Brown has been able to stockpile talent through relentless pursuit. He mails nine hundred handwritten notes to prospective players each year, and the recruits he wants the most grow accustomed to finding FedEx packages with letters of encouragement every Friday before their high school games. Even their parents can come to expect mail from the coach. And though he downplays the importance of his own role in recruiting (he tries to chalk it up to the work of his staff and, among other things, Texas and Austin being trendy places because of George W. Bush’s popularity), the search for new Longhorns is never far from his mind.

Just minutes after the magazine writer stepped out of Brown’s office, the coach reappeared in the doorway wearing a fresh change of clothes. He had traded his burnt-orange Nikes for leather loafers, his hair was perfect, and the smell of sweat was gone. He was already running a little late for a business lunch, but before he could get away, a staff member asked him to look at one of three possible covers for the new media guide. Each one featured Bevo, the stadium, and the Tower. The only difference was the image below the title: a football, a photo of the team coming out of the tunnel, and a close-up of the eyes of a player from an era long ago. Brown solicited opinions from his colleagues, but they preferred to let the head honcho go first. He then chose, hands down, the dullest of the three, the one with the football. Heads nodded in agreement, except for one staffer who was pulling for the team picture. It was “active,” he said, and gave the fans what they really wanted to see. “But why does that go against everything we preach around here?” Brown asked, seemingly enjoying having so many eyes on him. He pointed out that one player was clearly the most prominent. “Because everything we do is about the team, not the individual. Now, we have to have something that’s going to catch the eye of our recruits. We have to know what’s going to appeal to eighteen-year-old kids. But if we use Chris, people are going to say, why isn’t it [backup quarterback Chance] Mock? If we don’t use Cedric, people will say, ’Well, they didn’t use Cedric because he got into some trouble over the summer, and they’re mad at him.’” More nods of approval, then the lightbulb went off in Brown’s head. “What we could do is put our two Heisman trophy winners [Earl Campbell and Ricky Williams] in the front, and that would solve the problem. Maybe we should do that.” Universal nods of approval. “Okay, problem solved,” Brown said as he slapped some of his colleagues on the back. “I’m off to lunch.”

In the end, the problem wasn’t solved. Brown decided to let the team vote—and they chose the picture with the eyes. But it was a classic Brown moment: The CEO of Texas football is always selling the program, always considering his future recruits, and always thinking about the last detail that will one day put him over the top.

The Schedule

LAST YEAR, TALK ABOUT UT’S schedule centered on how easy it was. But could it have been too easy? In the Longhorns’ eleven wins last year, the team won by an average of 29.4 points a game. In its two losses, UT fell by 11 points to Oklahoma and 2 points to Colorado. Both games were decided in the final minutes, and when it came down to the big plays, the other team made them. This year the nonconference schedule has no tough opponents, but the talk about the conference schedule is that it’s too hard—Oklahoma in Dallas, as usual, and two top teams UT didn’t play last year, Nebraska and Kansas State, both on the road. Throw in Texas Tech on the road and archrival A&M, and that makes for a lot of hurdles just to get back to the Big XII title game. Yet playing tougher teams is just the thing this program needs to prepare itself for a title run. “I definitely think it makes us a better team to play a tougher schedule,” says Simms. “It’s all about being battle-tested. You look at OU two years ago—when they got to the national championship game, they had already played four national championship caliber games. When they finally played for the title, it was just another game for them, and that’s the way they handled it.”

It doesn’t hurt that UT’s most important opponents on the road don’t look as strong as usual. Kansas State suffered through a 6-6 season last year and returns only four starters on offense. And though no one in college football wants to play in Lincoln, Nebraska, the Cornhuskers have problems of their own. For one, the defense must prove that giving up 34 points in the first half against Miami in last year’s national championship game was an aberration. Second, the offense must get on track while returning only five starters. With Heisman trophy winner Eric Crouch gone, the leader of the offense will be a quarterback named Jammal Lord, a junior who has never started a game. And what of that vaunted magic in Lincoln, where the Huskers haven’t lost since October 31, 1998? Well, it doesn’t frighten Brown. He was the last coach to win there.

The Destiny

EVEN WITH ALL OF THE talent and the momentum built up over the past year, the Longhorns still need some luck to win the title. But if the success of the rest of the athletics department in 2002 is any indication, the football team may lead a charmed season. This year the men’s and women’s basketball teams both made it to the Sweet 16 of the NCAA tournament. The men’s swimming and diving team won the national championship. The women’s golf team came in second in the country, and the men finished third. Then in June the men’s baseball team won its first national championship since 1983. This success sets the stage for the perfect story. UT has the coach, the talent, and the depth, and Brown’s squad now needs only to believe one thing: They are destined to win the national championship.

“What we’ve learned is that we’re now good enough to have national rankings,” Brown says. “It’s hard when you’re not good enough, and you’re getting ranked anyway because of your traditions and your recruiting. We were plays away last year from going to the national championship. That’s where we want our program to be, and if you’re there enough, then you’ll win it.”