This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

They say you stuck your hand over the mouths of your children and suffocated them,” I tell Tanya Reid. “Then you brought them back to life with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. Then you waited a few days and did it again.”

“Oh, dear God, no, it just isn’t true,” she says quietly, brushing tears out other eyes, which are as soft and brown as a cocker spaniel’s.

We are in a small, locked visitors’ room at the state prison for women in Amarillo. Every two or three minutes, a heavyset female guard peers through the window to make sure I’m okay. But the guard is not really concerned. Thirty-seven-year-old Tanya seems timid. She wears oversized glasses that make her look like a fifties-era librarian, and her thick black hair is flecked with gray. When I ask if a photographer might take her picture, she apologetically refuses. She tells me that she has gained weight in prison and is embarrassed about her appearance.

“And if the other inmates recognize me in your magazine,” she says, leaning forward in her chair, “they’ll know I’m in here for child murder.” She catches her bottom lip between her teeth. “That’s the worst crime to be known for in a women’s prison, you know.”

It is one of the most curious murder cases in Texas legal history. On February 7, 1984, after suffering at least twenty episodes of infant apnea—a cessation of breathing that usually required resuscitation—Tanya’s eight-month-old daughter, Morgan, died in an Amarillo hospital, 48 miles from the tiny town of Hereford, where Tanya and her husband, Ray, were living. According to the autopsy, a contributing factor in Morgan’s death may have been sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), a catchall designation assigned to cases in which otherwise healthy infants mysteriously stop breathing, usually during sleep, and die. But nearly a decade later, an investigator with the district attorney’s office in Hereford reexamined Morgan’s death after learning that Tanya had been accused by authorities in Des Moines, Iowa, of inducing similar apneic episodes in her new baby, Peter (his name has been changed to protect his privacy).

Although no one saw Tanya do anything harmful to Peter, five Iowa doctors testified that they believed she had to have been smothering her son because he stopped breathing only when the two were alone together. In 1989, following a trial before an Iowa judge, Tanya was convicted of endangerment to a child and given the maximum sentence of 10 years. Then, in August 1993, she was brought back to Hereford to be tried before a jury on charges that she had murdered Morgan. Although there were no eyewitnesses and no clear medical conclusion about the cause of Morgan’s death, Tanya was found guilty and sentenced to another 62 years.

Even in a nation that has grown accustomed to brutal crimes, there remains something horrific about a mother who murders her children. After Susan Smith went on national TV last year with a tearful plea to the “carjacker” who kidnapped her boys and then confessed that she had drowned them in a South Carolina lake, public shock lasted for weeks. Surely, we told ourselves, she was a freak of nature. But now some experts are beginning to believe that far more mothers are driven to infanticide than we know. Many children may die as a result of Munchausen syndrome by proxy, in which a parent, almost always a mother, induces an illness in a child that requires medical tests and treatment. Although little is known about the syndrome, doctors believe that some of the parents hope to receive attention from concerned doctors, nurses, neighbors, and family members. They are said to get a bizarre sense of satisfaction from the attention—and if not stopped, they could end up committing murder.

“Although we have no hard statistics, this might be a problem of truly outstanding proportions,” says Linda Norton, a Dallas forensic pathologist with a national reputation as an expert in infant abuse and death. While Norton can cite instances in which mothers have given their children laxatives to cause diarrhea or injected feces under their skin to cause boils and abscesses, she says the most common manifestation of Munchausen by proxy is respiratory arrest. “I am convinced that doctors are attributing some deaths to SIDS when in fact the mother is deliberately inducing respiratory arrest in her child,” she says. “And the mother knows she can get away with it because it is almost impossible for a doctor to tell the difference between a child who has been suffocated and one who has accidentally had his airway obstructed.”

Without such evidence as a confession, a videotape of the act, or an eyewitness, how can doctors say for sure that a mother is suffering from Munchausen by proxy? Indeed, earlier this year, a Texas appeals court overturned Tanya’s murder conviction, saying in part that there was no proof she had used her hands as a deadly weapon to kill her daughter. The case may be sent back to Hereford for a new trial, and all the old questions are being asked again. Is Morgan’s death a murder mystery or is it a medical mystery? Is Tanya truly a monster or is she a victim of bad doctors and overzealous prosecutors?

Hoping to find out, I visited Tanya on several occasions earlier this year—the first interviews she has granted since her conviction. “It’s as if I’m the victim of a witch-hunt,” she told me. “Just ask yourself, Why would I want to kill my own babies? They were my babies. Is it right that I’m now called a murderer just because those doctors couldn’t figure out why my children stopped breathing?”

“I have to admit, Tanya’s case haunts me,” says Charles Rittenberry, a distinguished Amarillo lawyer who defended her in the Hereford trial. “Usually, if you’ve got a client who knows he’s guilty, he’ll eventually ask you what kind of plea-bargain he can get. But we came to Tanya three times with different plea-bargains from the district attorney. She was given a chance to serve only four or five years before getting out on parole. And she said, ‘No, I’m innocent! I’m not going to plead guilty to something I didn’t do.’ ”

For someone accused of being a deranged killer, Tanya Reid seems to have had a perfectly ordinary childhood. Gene Gerringer, an investigator for the Deaf Smith County district attorney’s office, spent months talking to people who knew her. “She was the typical small-town girl,” he says. “Her parents were good people. What can I say? There was nothing strange about her at all.”

Born in a middle-class neighborhood of the Panhandle town of Dumas, Tanya was the youngest of four daughters. Her father, John Thaxton, who died in 1990, was part owner of a medical supply company. Her mother, Wanda, worked in his office for fifteen years. In a brief but apt description of herself that she once gave in court, Tanya said, “I was raised as a Baptist. I was in the youth choir, and I sang in the church there. I played in the high school band. I played clarinet. Went to all the football games and basketball games. Just a normal growing up.”

“I’m not saying this just to impress you, but we were a genuinely close, loving family,” says Wanda, a slim, gracious woman who lives in the same modest home where she raised her children. None of the Thaxton girls was considered a troublemaker, and their parents kept it that way. On weekend nights, John and Wanda would drive around town to make sure the girls were exactly where they said they would be. The chief of police, who was John’s good friend, would call him if he saw any of the girls hanging around with the wrong crowd. “We were all afraid of getting in trouble because we knew somebody would tell my parents,” Tanya remembers.

On the wall of her den, Wanda prominently displays pictures of her daughters taken when they were high school seniors. She does not deny that the three older girls were prettier than Tanya. Leslie was named Miss Demon at Dumas High School, an honor similar to homecoming queen. Rodena was a twirler in the school band, one of the most glamorous positions a teenage girl can achieve in a small town. Beverly Kay entered the Miss Moore County beauty pageant.

Tanya, by contrast, was more reserved. She had her share of high school dates—she says she saw Jaws four times at the movie theater with four different boys—but she didn’t have as many close friends. She worked after school as a bookkeeper at a truck stop. She was a candy striper at the sixty-bed Dumas Memorial Hospital, and at night, she baby-sat for many families around town. Still, she says she never felt a sense of inadequacy. “If anything,” Tanya says, “I was the baby of the family. I was the one who was spoiled by everyone else. I was always paid a lot of attention.”

If Tanya was not as well known around Dumas as her sisters, all that changed in December 1974, when the Moore County News printed her photograph along with a story headlined TANYA THAXTON, BABYSITTER, RECEIVES GOOD NEIGHBOR AWARD. According to the article, Tanya won the award, which was handed out each month by the women’s division of the Dumas Chamber of Commerce, “when her calm thinking and quick reaction to an emergency resulted in a Dumas police patrolman saving the life of four-month-old Scott Simmons with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.”

Tanya, who had been Scott’s regular baby-sitter for about two months, says she was watching him one evening when he awoke from a nap and began having trouble breathing. She called her mother to ask if that was normal in such a small infant, and Wanda told her to call Scott’s parents. But when Tanya returned to the couch, she saw that Scott had stopped breathing. She quickly dialed the Dumas telephone operator, who in turn contacted the police. A patrolman arrived and gave the child mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The baby was kept in the hospital for three weeks before being released. “We feel [Tanya] was just superb,” Scott’s mother, Judy Simmons, told the News reporter.

Like a lot of people who have followed Tanya Reid’s trials, I have studied that article over and over. Did Tanya learn that by saving a dying baby, she could become as famous as her sisters? Or did she have the impulse to do harm at age seventeen? “i’ll be real honest with you,” Wanda Thaxton told me in her friendly way, patting my arm with her hand as if I were a lifelong neighbor. “Even though i’m Tanya’s mother, I have spent days wondering if Tanya, deep down, wanted to hurt babies. I’ve tried to think of some way she might have acted around children that would have tipped us off. But I cannot even recall a time when she got impatient with little children. And there’s another thing: If she wanted to hurt children, then why didn’t she try to harm any of the dozens of other children she babysat all over Dumas?”

“So you don’t think she would have put her hand over her children’s noses and mouths?” I asked.

“Well, she might have put her hand over their mouths,” Wanda replied, “but it would never have been done maliciously. I know there were times when one of my children was little and was acting up too much that i’d just real quickly put my hand over her mouth and tell her to quiet down.”

Wanda leaned over and softly put her hand over my mouth. After a couple of seconds, she pulled it away. It was, I have to admit, a benign gesture. “Just like that,” she said. “Just to get their attention. Most parents have done something like that at some point or another.”

“So Tanya would have seen you do that?”

“Oh, yes,” said Wanda. “But I never covered the nose—just the lips.”

What Tanya says about the Scott Simmons incident is that it was a turning point in her life, but not for the reason people think. “It just amazes me that people are now saying that the Good Neighbor award made me want to kill my own children,” she says. “It helped persuade me to get into medical care. At the time, I couldn’t help that baby. I didn’t know how to do CPR. I just sat there, helpless, until the police came. And from then on, I wanted to be prepared.”

After graduating from Dumas High School in 1976, Tanya entered the vocational nursing program at Dumas Memorial Hospital, where as part of her duties she helped care for the babies in the nursery. Around the same time, she became friendly with her family’s thin, sandy-haired next-door neighbor, Ray Reid, who had moved from New Mexico to work for Swift Independent Packing Company, a meat-packing plant. Ray was a rarity in Dumas: an eligible bachelor with an MBA making his way up the corporate ladder. Seven years older than Tanya, he was quiet, somewhat withdrawn, driven to make something of himself. “ou should have seen him,” Wanda says. “When he focused on that job, he thought of little else.” although at first Ray was friends with her parents, in February 1977 he asked Tanya out to see a horror movie. A few months later, while they were sitting in his pickup in her driveway, he proposed.

According to some people, Tanya and Ray made a good couple: Tanya, who had a way of chitchatting at length with people she liked, complemented the more subdued Ray. But according to others, Tanya and Ray had little in common other than the fact that they both thought it was time to get married. It is said that Ray was a demanding and unloving husband, that he refused to buy pretty clothes for Tanya but bought expensive suits for himself. (Ray would not be interviewed for this story.) Tanya says that when she tried to talk to Ray about their marital conflicts, he clammed up. “If there was a problem,” she recalls, “he had the ability to shut everyone else out.”

In October 1980 Tanya gave birth to their first child, Leslie (her name has also been changed). For the first two or three months, Leslie had a bad case of colic and cried most of the day and night. “It was a terrible burden on the marriage,” Tanya says. “Neither Ray nor I slept. We listened to her scream all the time.” Occasionally, when Tanya was too exhausted to walk the baby in the middle of the night, she would call her mother and ask her to come over.

For those people who have tried to portray Tanya as a psychopath, Leslie’s life poses a problem, because there are no documented instances of any serious medical maladies in her childhood. She was never taken to a hospital because she had stopped breathing. She was never hospitalized for any undiagnosed illness. And nothing unusual happened to her in the spring of 1981, when, according to Tanya, Ray and Tanya’s marriage began to fray. By then, Ray had been promoted to a position at Swift’s corporate headquarters in Chicago and moved Tanya and Leslie to a suburb of the city. Far from her family in Texas, alone throughout the day with a crying baby, Tanya told Ray she wanted to go home. Although they talked briefly about a divorce, they decided to stay together. They also decided to have another child.

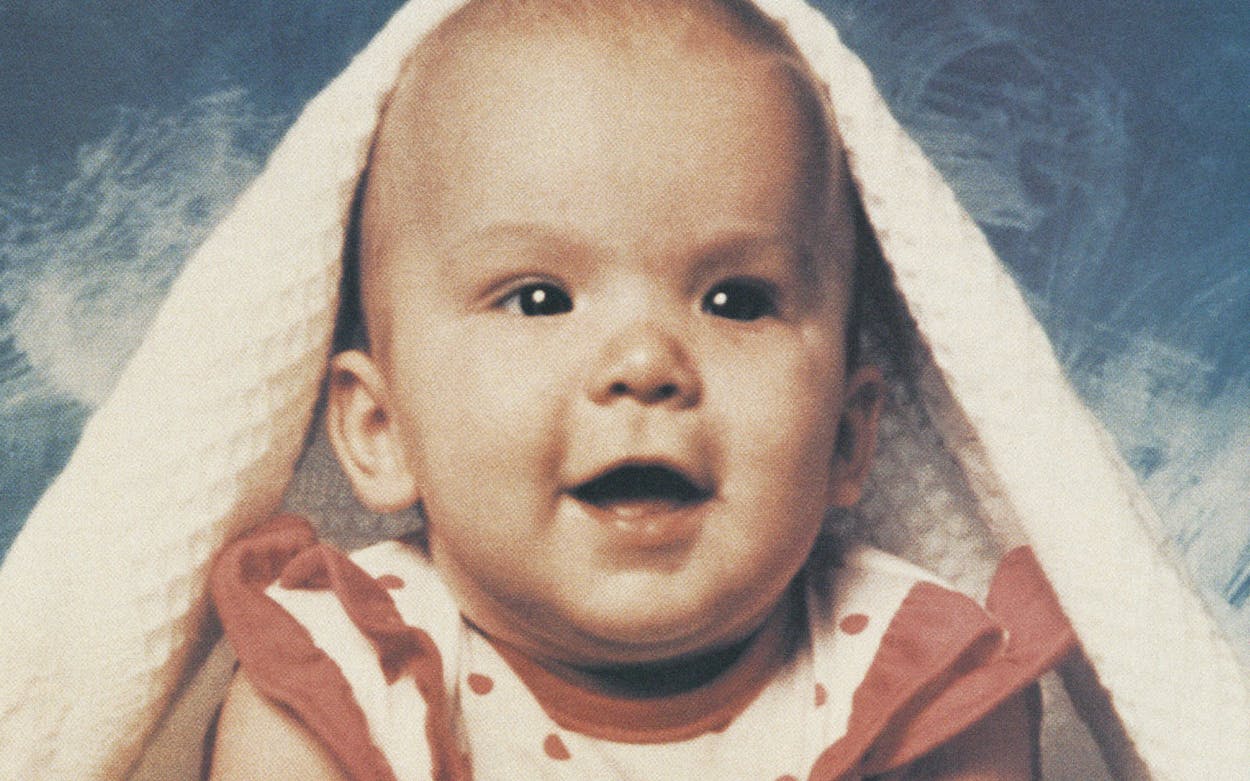

On May 17, 1983, Tanya gave birth to Morgan—“a very sweet, loving baby,” she says, “who loved to coo and curl almost into a ball every time you cuddled her.” But all was not well for long. Ten weeks later, Tanya says, after Morgan awoke from a nap, she fed her, laid her on her stomach, and walked out to get the mail. When she returned thirty seconds later, Morgan was “limp and blue and not breathing at all.” She called the paramedics and began to perform mouth-to-mouth. Within minutes, the paramedics arrived and took over the resuscitation until Morgan was breathing on her own.

Just as a precaution, a concerned pediatrician strapped an apnea monitor to Morgan’s chest, so a loud alarm would sound if she stopped breathing for more than twenty seconds. Less than two weeks later, the alarm went off. Morgan had stopped breathing again. Tanya called the paramedics and performed mouth-to-mouth until they arrived and rushed her to the hospital. After another two weeks, Tanya was back on the phone with paramedics, telling them that this time she had found Morgan lying on the floor, blue around the face, trembling slightly, and not breathing. The paramedics arrived and began working on the baby, and she sputtered back to life.

“It was more horrible than you could imagine, the kind of thing you would not wish on your worst enemy,” Tanya told me in the amarillo prison.

“But many people testified that you acted so cool and calm throughout these episodes,” I said.

“That’s what I had been trained to do from my nursing,” Tanya replied. “If you panic, how can you help your own child?” She shot me a confused look. “What are you thinking? That this didn’t bother me? My God! It caused Leslie to have nightmares. I couldn’t sleep at night because I kept thinking that apnea alarm was about to go off. Ray and I felt like this great weight was always hanging over us.”

At the Chicago-area hospitals where Morgan was taken, doctors checked for everything known to stop a baby’s breathing: extremely low blood sugar, an obstruction in the airway, a neurological problem, a heart problem. They conducted a variety of tests: an electrocardiogram, an electroencephalogram, chest xrays, brain scans, even 24-hour sleep studies to see if the baby stopped breathing at any point during the day. Specialists examined her esophageal reflux to see if she was choking on food that was regurgitated because of her weak stomach muscles. Time after time, they found nothing.

Bet the breathing troubles continued. In November 1983 Morgan had two apneic episodes in one day. Tanya and Morgan became the subject of constant talk. Some doctors were supportive and sympathetic, but one, a pediatrician named Jerry Skurka, began to ask out loud why Morgan’s episodes began only in the presence of Tanya, while Ray was at work or in a different part of the house. The one time Morgan suffered an apneic episode at a hospital occurred when she was alone with Tanya and the curtains were drawn around the bed. And why, asked Skurka, did Tanya always take Morgan home from the emergency room after the spells ended? If it were his child, he later said, “I probably wouldn’t let her out of the hospital until they figured out what was wrong.”

It just so happened that Tanya had been referred to Skurka by a clerk in his clinic, Lynn Jachimek, who lived directly behind the Reids. When Skurka took Jachimek aside one day and privately expressed his fear that Tanya might be inducing apnea in Morgan, she did not jump to Tanya’s defense. As she would later testify, she noticed Tanya was the kind of mother who got upset whenever the children became fussy. She also said that Tanya had once told her about a time back in Texas when Leslie would not stop crying: Tanya had locked herself in a room, called Ray at work, and begged him to come home because she felt she might harm the girl.

The more Jachimek talked with Skurka, the more upset she became. She had never seen Tanya cry about Morgan’s condition. She remembered babysitting Leslie one afternoon and seeing bruises on her back that didn’t look like the kind kids get from a fall. She recalled that Morgan’s first apneic episode occurred the very day that Ray was headed out of state for a training seminar that was going to interfere with their vacation. When Ray told Tanya she couldn’t come with him, Jachimek said, Tanya grew distraught at the thought that she was going to be left alone. (Both Tanya and Ray have denied this story, saying Ray was already back from the seminar when Morgan’s first episode occurred.)

After her talk with Skurka, an anxious Jachimek invited the Reids over for Thanksgiving dinner. Her teenage son got the family’s video camera and took plenty of shots of Morgan because, as Jachimek later testified, “We were afraid we would not see her again.” at one point, the video shows the Reid family on a couch. When Leslie, then three years old, starts crying and squirming, Tanya tells her to be quiet—but Leslie gets louder. Then, Tanya puts her hand over Leslie’s mouth, holding it there for only a few seconds, to get her to calm down. “I have never seen a parent do that,” Jachimek later testified.

But if Jachimek or Skurka had plans to keep an eye on Tanya, they didn’t get the chance. In December Ray was transferred to Swift’s office in Herefordsoon after the Reids arrived in Texas, Morgan suffered her eleventh apneic episode. When paramedics arrived at the Reids’ home, they found the same scene that had played out over and over in Illinois: Tanya on the floor giving mouth-tomouth resuscitation to the baby. Doctors at Dumas Memorial Hospital had Morgan flown by air ambulance to the prestigious Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston—but once again, after a battery of tests, the specialists found nothing.

One of the specialists who saw Morgan was Carol Rosen, an expert on children’s respiratory problems and the author of an article published the previous year in the journal Pediatrics about a rare affliction called Munchausen syndrome by proxy. In 1951 a doctor writing in the British medical journal Lancet coined the term “Munchausen syndrome” (referring to the eighteenth-century adventurer Baron Von Munchausen, who told tall tales about his exploits in war) to describe patients who faked illnesses to receive unnecessary medical care and, more important, attention and sympathy. It wasn’t until 1977, however, that another doctor wrote in Lancet about two mothers who had inflicted illnesses on their children and received the same attention “by proxy.”

Few doctors gave the syndrome credence. Usually, if a pediatrician dared suggest Munchausen syndrome by proxy as a possible answer to an unexplained illness, his colleagues were skeptical. But in her article, Rosen warned that doctors should be suspicious of mothers who bring their children to the hospital with a strange illness that occurs only when they are alone together. Rosen wrote about a case a few years earlier at Texas Children’s in which doctors could not understand why an infant girl kept suffering from apnea. Finally, a video camera was secretly placed in the girl’s room—and it captured the mother, a sweet-natured minister’s wife, placing her hand over the baby’s face until the baby stopped breathing, then resuscitating her until hospital personnel arrived.

To Rosen, Tanya Reid had all the characteristics of a Munchausen mother: She was a seemingly model parent with a background in medicine who acted overly calm when her child suffered. Then there was the story that nurses had told. While Morgan had been kept on an apnea monitor during her six-day stay at Texas Children’s, she had never suffered a single episode. But one afternoon, the nurses agreed to unhook the monitor from Morgan and allow Tanya to walk her down the hall. A few minutes later, Tanya rushed back into the room, telling the nurses that Morgan had suddenly stopped breathing.

Rosen asked the attending physician to allow a hidden camera to be set up in Morgan’s room to try to catch Tanya, but the plan never got a chance to work. According to Rosen, when she asked Tanya to keep Morgan admitted for a few days longer so that more tests could be run on her, Tanya refused, saying she needed to go home.

On February 7, 1984, back at the Reids’ home in Hereford and far from Carol Rosen’s prying eyes, Tanya called the paramedics to say that Morgan had stopped breathing. This time, no one could revive her. After doctors worked on her at the Hereford hospital, she was rushed to a hospital in amarillo. Although she was put on a respirator, a doctor told the Reids that Morgan was brain dead.

Tanya and Ray let Leslie come up and say good-bye to Morgan and then the respirator was turned off. Yet for the next fifteen hours, Morgan held on, her eyes half closed, her breath coming in tiny gasps. Family members took turns holding her throughout the night. Finally, on February 8, at 11:22 a.m., she stopped breathing. The pathologist who performed her autopsy found a subdural hematomableeding around the brain—which years later led some doctors and investigators to speculate that Tanya had panicked when trying to revive her unconscious daughter, that she had shaken Morgan so hard she killed her. But another pathologist would suggest that the hematoma could just as easily have come from the paramedics’ and doctors’ desperate attempts to revive her. In the end, no one could say for sure what caused Morgan’s death.

A few months after Morgan’s burial, Ray was transferred back to Chicago, and the family moved again. Not long after that, Tanya became pregnant. On May 2, 1985, she gave birth to a ten-pound boy, Peter. “a happy, happy baby,” she says. “He slept through the night, never bothering us a bit.”

Yet when Peter was just 26 days old, Tanya called the paramedics: She had found him unconscious and was performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to keep him alive. After Peter was admitted to the hospital, doctors performed every sort of test on him. But they never witnessed an apneic episode. Once, Tanya took Peter to see Shashikant Kudchadker, a kindly pediatrician who had treated Morgan when the Reids first lived in Chicago. When Kudchadker came into the examination room, he found Tanya bent over Peter, giving him mouth-to-mouth. Supposedly, he had lapsed into unconsciousness. “Help me, Dr. Kudchadker,” Tanya said. Kudchadker told her to take her mouth off Peter’s mouth. As soon as she did, Peter started coughing and his color came back.

Right away, doctors began asking the same questions about Peter that they had once asked about Morgan. But in July 1986, before anyone could do anything, the Reids left Illinois. Ray was transferred again by Swift, this time to amarillo—and for reasons that no one has ever been able to explain, Peter stopped having breathing problems as soon as the family returned to Texas. As a precaution, Tanya took him to see a respected pediatric neurologist in Dallas, Steven Linder, who was convinced that Peter was growing out of his condition. After also studying Morgan’s hospital records, Linder decided there was an organic problem in their brains. “These babies are abnormal,” he said. He did not believe, he would later insist, that Tanya had smothered either child.

By July 1987, when Ray was transferred to Des Moines, Iowa, it had been a year since Peter’s last seizure. t three months after the family’s arrival in Iowa, he stopped breathing again and was taken to Blank Children’s Hospital. He recovered quickly, but eleven days later he was readmitted after another seizure.

Once more, the Reids became the topic of conversation among a hospital staff. A pediatric nurse found it odd that Tanya took the time to smile at her while a suffering Peter was on his way to the intensive care unit. A paramedic who was called to the family’s home during one of Peter’s episodes said he arrived to find Tanya giving mouth-to-mouth to the limp, blue baby—but as soon as she moved away, he began breathing. “I mean, a split second and he was breathing at that instant,” the paramedic later said.

In February 1988, when paramedics rushed Peter to the emergency room yet again, a nurse, Callie Jo Sandquist, noticed four fresh scratches cutting across his right cheek. While the baby wailed, Tanya talked calmly to Sandquist, using her large medical vocabulary to describe his symptoms. Tanya said that Peter had torn at his own face during his seizure and that she had even gotten a scratch on her own finger trying to control him. Sandquist had never before heard of a child scratching himself at the onset of a seizure. Usually, a child stiffens up and clenches his fists. “My God,” she thought, “what if Peter got those scratches trying to push his own mother’s hand off his face?”

Unsure of how to proceed, doctors at the hospital called a child protective investigator for the Iowa Department of Human Resources, who interviewed Tanya and Ray. Both denied that Tanya had done anything wrong. With no conclusive evidence to the contrary, the investigator let them take Peter home.

If Tanya had been abusing Peter, perhaps she would have been smart enough to stop—at least until Ray got transferred again. She had to have known that doctors and law enforcement officials were monitoring her every move. But less than a month later, she called the paramedics to her house. This time, as they lifted Peter into the ambulance, Tanya told them to take him to a different Des Moines hospital than the one he had previously been to. When the admitting physician, who knew nothing about the case, asked for the boy’s name, Tanya didn’t use “Peter.” She called him by his middle name.

Tipped off by a policeman familiar with the case, juvenile authorities learned of Peter’s latest relapse and they became convinced that they had to intervene. They persuaded a judge to remove Peter from his parents’ custody and place him in foster care, and immediately things improved. For the first three years of his life, Peter had been hospitalized at least fifteen times and subjected to hundreds of tests, but after he was taken away from Tanya, he never had a seizure or breathing difficulties again.

Peter’s case was referred to the Polk County attorney’s office in Des Moines, where it was assigned to prosecutor Melodee Hanes. A specialist in child abuse, Hanes had learned about Munchausen syndrome by proxy from articles given to her by her investigators. Though she had read that it was nearly impossible to prove that a mother suffered from the syndrome, she set her sights on Tanya. She spent months hunting down nearly every doctor who had seen Tanya and her children over the years. She decided to expand her inquiry to include not just Peter’s apneic episodes but also her suspicion that Tanya had murdered Morgan.

In February 1989 Tanya was tried on charges of endangerment to a child. Unmoved by Hanes’s case, Ray testified for his wife. “How could she dupe me for that long a period of time, for four or five years?” he asked, looking genuinely baffled. Their eldest daughter, eight-yearold Leslie, testified that she had never seen Tanya hurt Peter and that Tanya had never tried to hurt her. And the one doctor who seemed to believe Tanya was innocent, Steven Linder of Dallas, told the judge that the other doctors accusing her had downplayed the possibility that the children’s breathing problems were neurologically oriented. Linder seemed astounded that the other doctors could diagnose Munchausen syndrome by proxy without conclusive criminal evidence, such as a videotape of Tanya smothering Peter. But Thomas Kelly, a pediatric neurologist from Des Moines, said that even if Peter had a malformed brain, it would not have caused his breathing trouble—so the apneic episodes had to be coming from another source.

The judge ultimately considered it too much of a coincidence that Tanya was present at the beginning of each of Peter’s episodes and that they ended almost immediately after Tanya was separated from him. At the end of the trial, he pronounced Tanya guilty and sentenced her to ten years—which, according to Iowa’s early release provision, really meant only five years behind bars. Tanya bowed her head and wept. Before being led away, she hugged Ray and told him she would be back home soon.

But Tanya’s troubles were far from over. In March 1993 the Deaf Smith County district attorney’s office indicted Tanya for murdering Morgan in 1984. With no concrete answer about the cause of Morgan’s death, prosecutors used much of the evidence presented at the Iowa trial, and they relied on testimony from Tanya’s former Illinois neighbor, Lynn Jachimek, and from Morgan’s former doctors—everyone from Jerry Skurka, who had seen her in Illinois, to Carol Rosen, who had seen her in Houston.

Tanya’s attorneys, led by Charles Rittenberry, attacked the doctors, claiming that they were blaming her because they could not figure out why Morgan had died. “This case reminds me of every mom’s nightmare,” Rittenberry told the jury. “The Munchausen by proxy just simply doesn’t fit anything except that it does what it’s designed to do: to get you to convict on insufficient evidence.” Tanya again tearfully testified that she was innocent, and Ray also took the stand. By this point, he and Tanya were divorced. (Tanya says they had agreed to divorce to make sure that Ray, rather than the state, got custody of Leslie and Peter.) He had remarried and was living outside Texas. He acknowledged that Peter continued to live apnea-free in the time he had been kept from his mother. Still, he firmly told the jury that Tanya would have done nothing to hurt her children. It wasn’t clear if Ray, by some accounts an aloof husband, had ever considered the possibility that Tanya used the seizures as a way to bring them closer together, though he did admit, “Well, when it was just her and I together, there was many nights that she cried most of the night because she didn’t know what was happening.”

But the most powerful testimony for the prosecution had come from a new witness: Judy Simmons, the mother of Scott Simmons, the Dumas boy Tanya baby-sat back in 1974. Simmons told the jury that the now nineteen-year-old Scott was physically handicapped because oxygen to his brain had been cut off that night—the first and last time such an incident occurred. “He will always have problems from this episode,” she said. “Children are cruel anyway in school . . . but to a child with a handicap, they are more so.” Simmons looked at Tanya and began to sob.

After only three hours of deliberation, the jurors found Tanya guilty and sentenced her to 62 years. A few days after the trial, in the Hereford jail, she was allowed to see Peter, who was then eight. He had been out of her custody for five years. According to doctors, he had caught up with other children emotionally, but he was still developmentally delayed because of his past seizures. Peter and Tanya held hands through an opening in a screen. “are you not coming home with me, Mommy?” asked Peter, who had been told that Tanya was out of the state studying at a college.

“No, Peter,” said Tanya. “i’m going to have to stay in prison because of false things other people have said.”

“Mommy,” he said, “why do you have water in your eyes?”

“Because it might be a long time before I get to hug you again.”

As I listen to Tanya tell me this story more than a year later, I am not certain how to react. When I suggest that she’s guilty, she seems dazed with disbelief. When I suggest to her that perhaps she never meant to kill Morgan, that she just went too far on that one occasion, she looks at me as if her heart is about to break. “Never would I do something like that to my baby,” she whispers in her soft, flat voice. When I ask her why Peter hasn’t had a seizure since they’ve been separated, she says, “Why doesn’t anyone believe Dr. Linder, who said it’s possible a child can grow out of his seizures?”

As I talk to Tanya, I keep expecting to find some disturbing aspect of her personality—a sign, perhaps, that she is crazy. t a clinical psychologist who has examined her four times says, “I have no reason to believe that Mrs. Reid suffers from a psychological disorder of any kind.” I want Tanya to admit her failings as a mother, but the closest she comes is to say that if she ever gets out of prison she won’t have any more children. “I know people would be watching me too close, staring at my every move,” she says. The truth is that her date of release might not be that far off. Since she has served enough of her Iowa time to be released and her Texas conviction has been thrown out by the appeals court, neither the prosecution nor her lawyers are particularly enthusiastic about a retrial—and she could be offered a plea-bargain.

“What will you do when you get out?” I ask.

“Oh,” she says, her face lighting up. “i’ll go home and let my mother cook one of her old-fashioned meals for me, just like she used to when I was a girl. And i’ll get to hug my kids again. I’ll put them on my lap and tell them that even though they have a new mother, i’ll always love them.”

For a moment, I imagine Tanya hugging her children. Perhaps, I think, now that they are older, their relationship will be more peaceful. But I cannot forget that videotape shot long ago by Lynn Jachimek’s teenage son. There is Tanya—gentle and round-faced—slipping her hand over Leslie’s mouth, just like her mother once did to her. “Hush up,” she says in the video, pushing lightly with her hand.

For a moment, the little girl squirms and then she’s still.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime