The wind blows in every night at the McAllen ballpark at a steady 20 to 25 miles per hour from left field, carrying dust and occasional debris. On the bench it would be smarter to stay upwind of the snuff dippers and Redman chewers, but since everyone on the team has a mouthful of tobacco the best one can do is keep some distance and avoid the weak spitters. The McAllen team plays on a field rented from the city’s high schools. As there is no locker room, the visiting Corpus Christi Seagulls will have to shower in their motel rooms. The outfield grass is mostly brown from the midsummer sun, and not very smooth.

Though the players line up reverently before the game with their hats over their hearts while the scratchy press box phonograph blares out a tinny version of the National Anthem, there is no flag on the premises to salute, or even a flagpole. During the first three or four innings the left fielder, shortstop, and third baseman stare directly: into the setting sun. From left field it is impossible to follow a pitched ball at all, even with sunglasses: a player can only listen for the sound of ball hitting bat, wait for teammates to shout, and worry. The fielding statistics by which a ballplayer’s future are in part determined will not record several innings of functional blindness. There will be no asterisk noting the dark spots on the field after the lights are turned on, or the odd bounces now and then. At third base the fear is more elemental: a line drive, coming out of that sun could fracture a player’s skull before he could raise his self-defense.

By game time fewer than 130 paying customers have scattered themselves randomly on the rickety open bleachers on the McAllen Dusters’ side of the field. Behind the visitors’ dugout there are exactly two: Bobby Flores’ girlfriend and Rick Buckner’s date. Flores is a utility player—a baseball euphemism for a second-stringer—and Buckner the regular third baseman for the Seagulls. Considering last night’s game it is a wonder anyone other than blood relatives of the players has come at all. The Dusters have the worst record in the league, having won 9 and lost 21. Corpus Christi has won 13 straight and is one win away from clinching the first half pennant in their division. With 24 wins and 6 losses they have the best record in professional baseball.

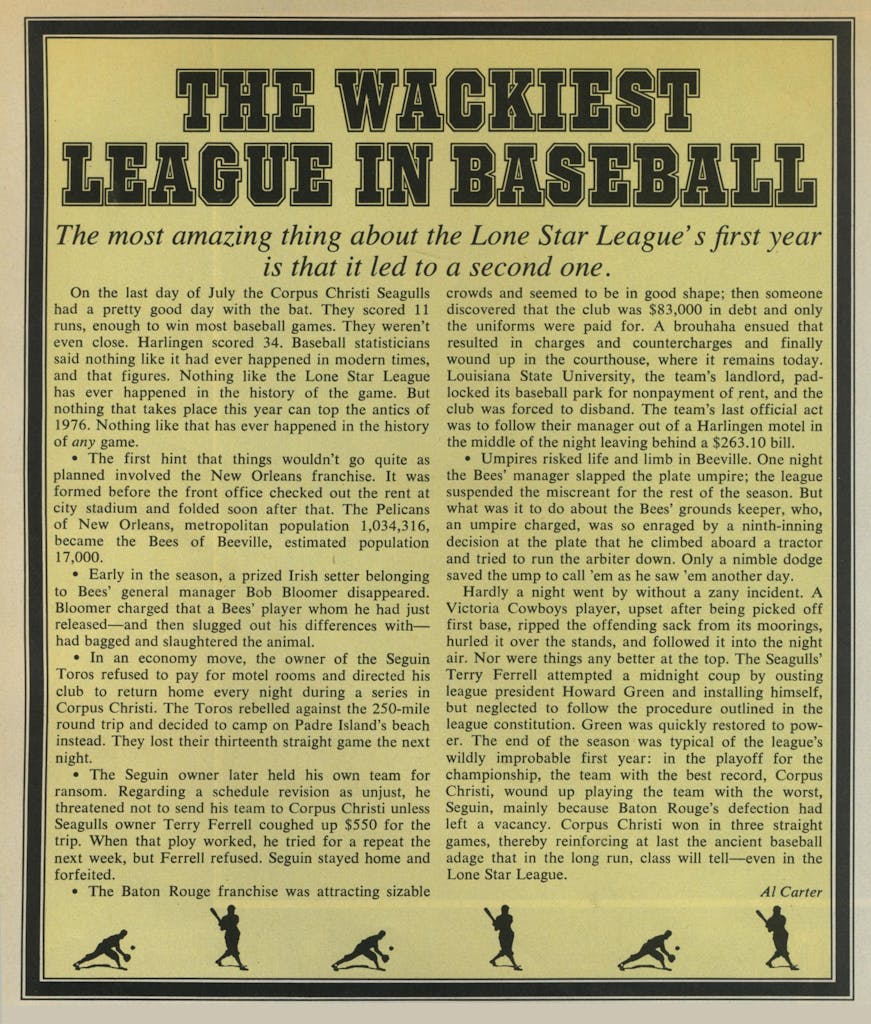

The Seagulls’ nearest league rivals, the Harlingen Suns, are 9 games behind with 10 to play and have only broken even in 30 games. Last night McAllen, arguably the worst professional baseball team in the United States, made ten errors, including four in the second inning alone, gave up nine unearned runs and handed the game to Corpus Christi 11-0. Against Ken Palmer, a former University of Oklahoma pitcher who has yielded less than two earned runs a game, McAllen managed just four weak singles, no walks, and struck out eleven times.

By the late innings the Corpus Christi players were openly contemptuous of McAllen’s lack of effort. For them there was neither joy nor honor in defeating a team that was not trying. McAllen has been a troubled, feuding club all season—primarily, the Corpus Christi players believe, because of second baseman Billy Gautreau, whose father owns the franchise and who they believe could not make the roster of any other team in the league, much less start. They are convinced that the Gautreau controversy cost Mike Krizmanich, an outfielder who played for the Seagulls last year and won the league batting title with a .381 average, his job as McAllen’s manager. By the end of the game the only thing that moved them to animation was the hope of knocking Gautreau down by sliding high and hard into second base. Like all ballplayers, they bitterly resent any trifling with the verities of their game. Such things are occasionally done in high school; it is not the way professional teams operate. Being professional is very important in the Lone Star League.

The Lone Star League is unique in professional baseball. It is the only independently franchised minor league operation in the United States. With the exception of a couple of teams in the Pacific Northwest, every other professional baseball team in the country, and every player on each of those teams, is under contract to one of the 26 major league organizations. But not the Lone Star League or its players. It is the last remnant of the way minor league ball used to be, the boondocks of baseball.

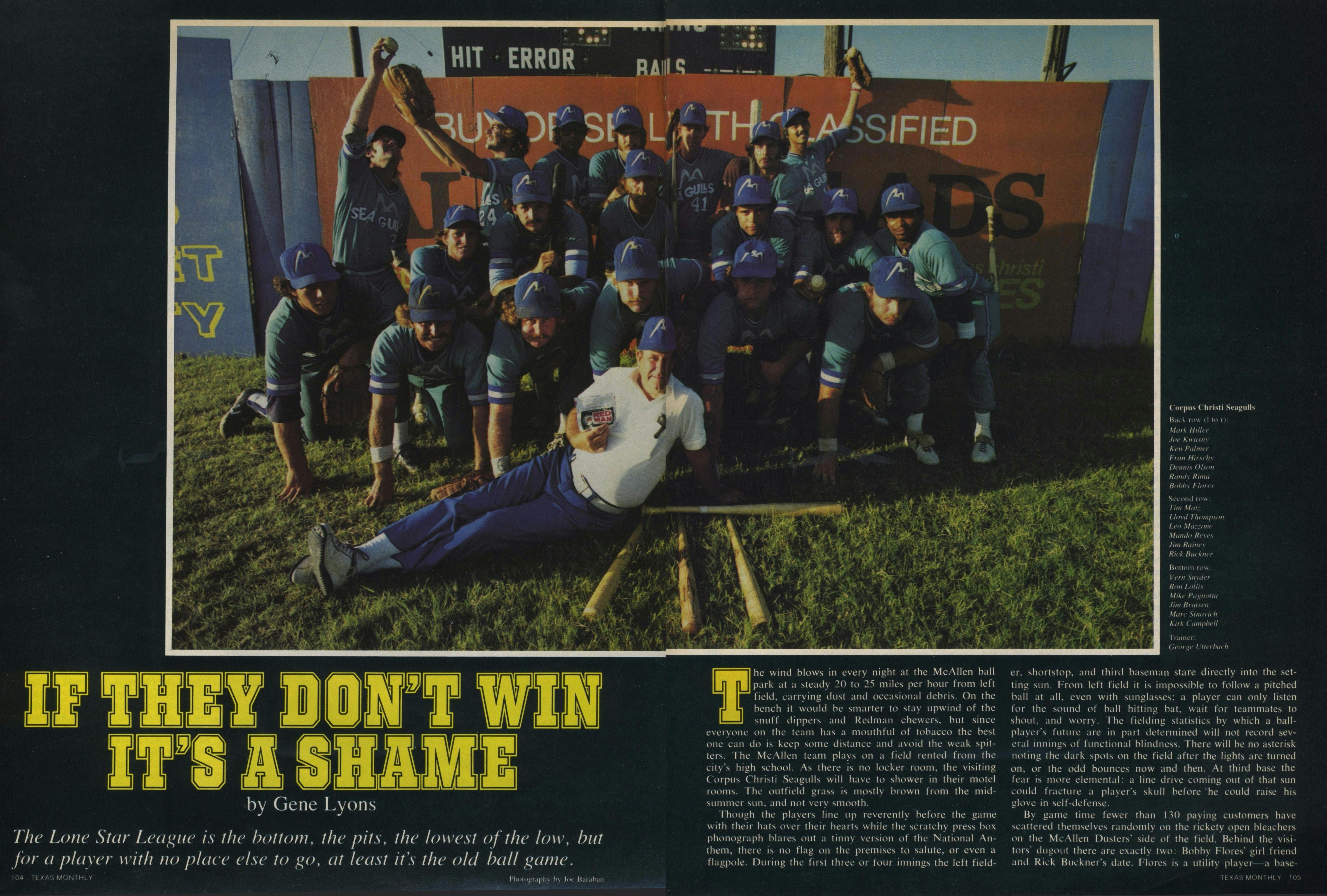

Bobby Flores, who is from Robstown and played college ball at UT-Arlington, characterizes his team as a “collection of oddballs, misfits, and old people, but a winner.” What he means by oddballs and misfits is that, despite the Seagulls’ gaudy record, no player was worthy of a current contract with one of the major league teams (though a few Seagulls would qualify as oddballs by any definition); what he means by old people is that the Seagulls have two players who are actually 25, and a number of others over 22. Among the eighteen Seagulls the twelve with previous pro experience have played for 33 other minor league teams in eleven states. Manager Leo Mazzone was a left-handed pitcher for ten years in the San Francisco Giants and Oakland A’s farm systems, getting as high as Tucson in the AAA Pacific Coast League before being released, with stops along the way in Medford, Oregon; Decatur, Illinois; Amarillo; Monterrey, Mexico; and Birmingham, Alabama. Catcher Ron Lollis, 25, was drafted in the sixth round out of a Spokane high school in 1971 by the Oakland A’s, turning down a baseball scholarship to Stanford. He played for teams in Oregon, Iowa, Alabama, and Florida (Key West) before making it two years ago to the top of the minor league ladder, the Texas Rangers’ AAA farm club back home in Spokane, but the word is that he had trouble hitting a slider. Fortunately for Lollis, not many in the Lone Star League can throw a good one, and he is murdering the ball again. But this time he is doing it on his own: he was released at the end of last season. The only one of the Seagull players who is married, L. O., as he is called, sold his house in Spokane to give it one more shot.

It is not hard to understand why, from Lollis’ perspective, the sudden end to his career made no sense. There he was, moving up each year, still only 25—and then it’s over. His experience sheds light on an aspect of baseball familiar to all players and virtually no fans: professional baseball, often eulogized by intellectuals and traditionalists as a reminder of an older, more bucolic America, is in fact as bureaucratic as, and a good deal more relentlessly hierarchical than, such pursuits as banking, life insurance, and the teaching of comparative literature. Lollis was cut, not because he couldn’t hit the slider, but because he was 25 and couldn’t hit the slider. He was dropped to make room in the organization for the class of 1977, some of whom were 18 and 19 and had never seen a slider. Flores’ characterization is apt: most of the Seagulls are too old, even at 21 or 22, to be playing ball at this low level and retain much hope of making it to the big leagues, or even the high minors. For a very few it may be a beginning; for most it is the end. But they all have hope; without that, playing here for $400 a month would make no sense at all.

Minor league baseball has not always been so cut-and-dried. Before television’s drastic impact on virtually all public entertainment, from movies to sports, there were far more minor league baseball franchises in medium- and small-sized cities all over the country. Until 1958, in fact, the only major league team west of the Mississippi was the Saint Louis Cardinals (the Browns moved to Baltimore in 1953), whose home park was a short walk from the river. In those days it was quite common for ballplayers to have long minor league careers and to remain with one club for a considerable number of years: names like Eddie Knoblauch, Larry Miggins, and Jerry Witte are still familiar to postwar Texas league fans. Today a ballplayer seldom lingers for long in the minor leagues; Leo Mazzone’s experience is unusual and, except for pitchers, almost unheard of.

In 1953, for example, there were 306 minor league teams operating in 38 leagues around the United States and Canada, and an elaborate classification system that rated the quality of play from the AAA International and Pacific Coast leagues, through the AA Texas League and Southern Association, all the way down through Class A, B, C, and even D. There were leagues with colorful names and long traditions, like the Pony League (an acronym for Pennsylvania- Ohio-New York) and the Three-I League (Iowa-Illinois- Indiana). In Texas the current major league cities, Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth (unhyphenated in those years), were in the AA Texas League, but 28 other Texas teams were in the Big State League, the West Texas-New Mexico League, the Arizona-Texas League, the Sooner State League, the Gulf Coast League, and the Longhorn League. Beaumont played in the same league with Houston, and Austin, Galveston, and San Angelo all had franchises. Even towns as small as Gainesville, Paris, and Lamesa were represented. By 1976, though, there were just 16 minor leagues left, several of them for rookies only, and 100 or so teams. Besides the Lone Star League, the only minor league teams left in Texas are in the four cities composing the Western Division of the Texas League: San Antonio, El Paso, Midland, and Amarillo. The majority of teams in the minors operate at little or no profit and are run by and for the major league clubs that own them. Consequently, the minors are no longer so much a training ground for young players, a place to learn the subtleties of the game, but rather a testing ground: put a player in the lineup, rate his ability to help the big club, and then move him up or move him out. Except for the Lone Star League, pro baseball is a closed shop.

The effect of this shrinkage upon the individual’s career has been to speed things up considerably, as well as, from the player’s point of view, to lend an air of capriciousness and mystery to the whole process. During his last season in AAA ball, Leo Mazzone was one of the few players able somehow to get a look at the scouting report written about him. He can give it to you word for word: “Big league curve ball, good change-up and slider, medium fastball. Short, very aggressive. Won’t help anybody.” In something over 1000 innings, he says, he had a 62-58 record, mostly as a reliever, where won-lost percentages mean relatively little, along with 1740 strikeouts—more than one an inning—and only 300 or so walks: very impressive statistics. One would think that anybody who could strike batters out at that rate and be around the plate so often would deserve a shot, at least, at some big league club’s bullpen. But the A’s, who released him, evidently thought not. “What the hell does that mean?” Leo still wonders. “Short, very aggressive. Won’t help anybody?” He can recite lists of short pitchers (he is 5’9″), commencing with Whitey Ford, who was 5’10”. As for aggressive, when he was with Amarillo, Leo once threw a ball clear out of the Memphis Blues stadium and into the Liberty Bowl when his manager came to take him out of a game. When Amarillo played at Little Rock he used to flash the Hook ’em Horns sign at fans from the bullpen, although, being from Maryland, he doesn’t really give a hang for them or the Hogs.

Leo’s ten years in the minors gives him cause to sympathize with Mando Reyes, a right-handed pitcher for the Seagulls who as of this writing had given up just four earned runs in thirty innings and won three games against no losses with three saves. About the same height as Leo but with a slighter build, Reyes, who compiled an 18-2 won-lost record in two years at Pan American University, was ignored in the professional draft, probably because of his size. Anyone who follows major league baseball must have noticed that young pitchers seem to be growing bigger each year: it appears that 6’2” or so must be a mandated minimum. Further affecting pitchers is the tyranny of velocity. Although there are any number of big league pitchers who have done and continue to do well without blazing speed—it used to be said of San Francisco’s Stu Miller that he couldn’t throw a baseball through a wet tissue—anybody who can throw the ball 90 miles per hour or more and get it near the plate fairly often is virtually assured of a big bonus and every chance to make good. Baseball people—the ultimate realists—are aware, of course, that pitchers who rely on guile and deception can get batters out, but they are also aware that it takes a good deal of time and cunning for breaking ball pitchers to sharpen their skills sufficiently to fool big leaguers. But until they get to the top and learn the tricks of their trade, by which time a good deal of expertise and many dollars may have been expended on them, nobody can be sure they’re worth the risk. So scouts put a radar gun to a pitcher’s fastball, and if, like Ken Palmer’s, it barely teases 85 miles per hour, even though he pitches lots of shutouts and hardly walks anybody, they write him off and he comes to the Lone Star League. Or if, like Dennis Olson, he has a bad day when the scouts show up, the same thing happens. Olson, who until early June pitched for the University of Missouri at Saint Louis, thinks he has the velocity but had a terrible day in NCAA playoffs when the scouts came. It was so terrible, he says, “you could have timed my fastball with a sundial.” Other players encounter other problems. With millions going to free agents like Reggie Jackson, player development dollars must be carefully watched. The late bloomer or the very talented player who was drafted low or signed for little money has a built-in disadvantage against a rival in whom the organization has invested heavily. Put simply, Mazzone says “a player they have put money into has to screw up badly; he has to play his way out of the lineup. The guy who got no bonus has to play his way in.”

Politics plays a part too. For Marc Sinovich—whom you would recognize as a catcher even in black tie and tails, assuming anybody could get him to wear either—the problem was being labeled, he thinks unfairly, as a troublemaker. In the Oakland organization, Sinovich roomed during 1976 spring training with a player who for some reason set his alarm clock one time zone west of where they were, causing Sinovich to miss a bed check by a few minutes. He was fined $100. Called up to the big club the next day to catch batting practice, Sinovich made the mistake of complaining about the fine to Reggie Jackson, who was infuriated by the story and promised to pay the fine himself. Jackson called in pitcher Ken Holtzman, the A’s player representative, who knew that fines were not to be levied in spring training against rookies with no big league contracts. Holtzman called Charlie Finley, Oakland’s owner, to complain; Finley reportedly called the minor league manager responsible and gave him a dressing down, and 24 hours later Sinovich, who had had a good year in 1975 in AA ball at Birmingham and was hoping for a AAA contract, was given his release by the same manager. So last year he came to Corpus Christi, where he hit .317, had 11 home runs and 64 RBIs in 74 games for the Seagulls, performed excellently as a defensive catcher, Leo says, and hit two home runs in the final playoff game despite a broken finger. But he has been injured this year and in any case is getting long in the tooth. Like Lollis, he is 25.

Lloyd Thompson came out of the University of New Mexico in 1975 (as did right fielder Randy Rima and second baseman Mark Hiller) and signed with Montreal. Early on he hurt his shoulder sliding into second base to break up a double play. During corrective surgery in the off-season a large screw was improperly placed, so that to extend his left arm with the palm raised was impossible—rather inconvenient for a shortstop—and to follow through on his swing at the plate was agonizing. He played badly and was cut.

“There were too many young guys sitting on the bench for them to keep fooling with me,” he says. When I remarked that 21, which he was then, seemed young enough to me, Thompson laughed. “We had two sixteen-year-old Puerto Ricans on that team.” Last winter he had the faulty screw removed and on the advice of a scout came to Corpus Christi to try his luck as a pitcher, as he has what the players call “a good hose.” But when Leo saw him in the field he went back to shortstop, where he is one of the players the manager thinks has a good shot at a second chance. He fields brilliantly and is hitting .300, so maybe he does.

Some players never know why they are cut. Unlike, say, the academic world, where someone dropped from the teaching roster can appeal to seventeen committees and stick around for a full year after the decision is irrevocable, baseball teams do the deed with finality. Joe Kwasny, who was drafted in the tenth round and signed out of high school in Virginia Beach, Virginia, by the Yankees—“the same year and the same round as Mark ‘The Bird’ Fidrych; my dad always reminds me of that”—is a case in point. Kwasny, who had pitched, he thought pretty well, for three minor league teams, came to his locker on the last day of spring training in 1976 to find it empty. “Usually they come to your room early in the morning, before anybody gets up,” he says. “But they just cleaned me out, even my hat, which they usually let you keep. I got the point. I went to the manager and he said pack your stuff. They had me on a plane by noon. That night I was back home watching TV with my father. Then Leo called me up and asked me to come down, and here I am. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I hate going to school, so that’s out.”

Kwasny starts the night of the second McAllen game, and I sit in the stands a couple of innings with Carl Sawatski, who caught for several major league teams in the forties and fifties and is currently president of the AA Texas League. Sawatski is paying a series of honorary visits to the owners of the Lone Star League teams. I ask him what he would be looking for if he were scouting the teams tonight. In pitchers, he says, velocity. Do either Kwasny or Laconia Graham, the Dusters’ pitcher, have it? In a word, he answers: “No.” But Kwasny, I say, signed with the Yankees just three years ago at eighteen. Most athletes don’t get their full strength until their middle or late twenties. What could have happened? “Either somebody made a mistake or he lost it.” Which is likelier? “A mistake.” But what about Stu Miller, I go on; he got people out with no real fastball at all. “Not when he first came up,” Sawatski says. “I knew Miller back in 1948 or ’49 when he first came into the minor leagues. He threw very hard then. He learned all that other stuff after he was up.” Sawatski is a friendly and amiable man, but about baseball, and particularly about pitchers, the former catcher’s negative judgments are swift, confident, and severe. Kwasny’s lack of a fastball to him is a fact, like the color of his hair.

Sawatski is able to stay only until the middle of the fourth inning and does not see Kwasny get really hammered, or the flaccid Seagulls do a passable imitation of McAllen’s fielding display of the previous night. Before he is taken out with one out in the sixth, Joe has given up eleven hits and six runs, three of them earned. In the dugout for the rest of the game and all the way back to the motel he doesn’t say a word. By the next morning he is joking about it. What else can he do? The loss is his second against five wins.

It is the maddening indeterminacy of baseball that makes it the crudest game. If games offer any lessons for life, which I think they do, what this one teaches is humility. It is not simply that the Seagulls have been beaten 8-1 by a terrible team; it is that games like this happen all the time in baseball, every night at every level of the game: the worst teams beat the best ones. To be a successful baseball team you must win six out of ten games; to achieve last place four of ten will usually suffice. There are nights when Dad himself could play second base, or Mom for that matter, nights when a team could field a butterball turkey or no second baseman at all and still win. The indirectness and subtlety of baseball’s competition is what makes it so productive of self-perpetuating illusions of greatness and finally so fascinating a game. At every level the bad news about one’s prospects takes just a little longer to become apparent; often when it is most obvious to everyone else, it is least discernible to the individual player himself.

Consider batting, the most directly competitive and immediately quantifiable aspect of baseball. As of this writing the leading team for average in the major leagues is the Cincinnati Reds and the worst is the New York Mets. Virtually every hitter who comes to the plate for the Reds exudes an aura of menacing competence: yet in round figures their team batting average translates to 29 hits in every 100 times at bat. The Mets, by contrast, seem as a group transfixed by feckless mediocrity: their team percentage is roughly 24 hits per 100 tries—a difference of less than two hits a game. Coming a bit closer to home we find that at the same point in the season the Corpus Christi Seagulls were batting .277 (or 27.7 hits per 100 at bats) to the McAllen Dusters’ .271 (or 27.1 hits per 100 at bats). Yet Corpus Christi had scored 205 runs by that point to McAllen’s 87, and no observer who had seen both teams play several times would mistake one for the other. It is this aspect of the game that makes a professional organization like the Lone Star League possible and provides its character.

Another thing easily lost in writing and reading about sports that are less than major league is that by any reasonable measure, these are extraordinary athletes. All of them have been stars everywhere they have played before now. Jim “Bear” Bratsen looks to have been made from the mold for God’s own first baseman. When he was playing for Texas A&M he got some All-America mentions. Pitcher Fran Hirschy broke every record Long Island University ever had. When Mike Pagnotta and Jim Rainey, the left and center fielders, come to the plate, they look like the good hitters they are. Everybody on the team can throw harder and more accurately than anybody I had ever played with—sandlot, high school, or anywhere else. If Joe Kwasny or Vern Snyder, or, for that matter, Leo Mazzone could today accept the collegiate athletic scholarships they could have had after high school, they would all be stars in the Southwest Conference. Yet here they are in the Lone Star League, which is as low as you can get in baseball and not be paid in beer instead of money. Even if they get the improbable break, the odds remain overwhelmingly against them. Making it to the big leagues is about as likely, statistically, as being elected to Congress. In all probability, there will be more turnover in Texas’ top three political positions—two senators and a governor—in the next ten years than in the Boston Red Sox outfield.

Traveling with a team of minor league ballplayers is like spending a week with an athletic-minded college fraternity—except that the physical conditions are more in keeping with the McAllen ball park than a plush frat house. The Seagulls started the season making road trips in a Dodge van, but one died before I got there and a second was lost on the way south when the hood flew up and smashed the windshield, so now they travel in private cars. The tone of most discussions, for anyone unfamiliar with such baseball literature as Jim Bouton’s Ball Four, could not be described as elevated. The players talk about sports, but not in terms much more sophisticated than the average fan would use. Anyone eavesdropping in hopes of picking up the finer points of the game would remain unenlightened. The sole indication that these are athletes talking rather than fans is that they are more likely to challenge conventional wisdom: one such discussion raged over whether basketball superstar Julius Erving was overrated. But no one had any harsh words for any baseball major leaguers.

When they’re not talking about sports, their competitiveness is expressed in continual ragging, teasing, and petty bickering, none of it serious on the Seagulls since they are winning. They talk about women, or more precisely, they talk about sex, even in the dugout.

“You call that a seven, man? I wouldn’t give her a five.”

“Well, Jesus, I didn’t study her, I just looked. She’s got a pair of big league headlights on her.”

“But look at the face. That’s no seven.”

“Well I didn’t inspect her to see if she had zits or anything, I just looked quick. OK, a six.”

“Six? Hey, c’mere and look at what he calls a six.”

They talk about drinking, sometimes about fighting, about cards, and endlessly re-create, analyze, and laugh about things that have happened in games or on the road that illustrate foibles of their teammates or opponents:

“Did you see Medeiros act like he was trying to climb a twenty-foot fence after that pop-up?”

“You gotta try to be as big an asshole as that. I bet he wears that helmet of his in the shower.” (The player in question, the Harlingen catcher, wears an Oakland A’s batting helmet he brought with him from an assignment there as bullpen catcher. It clashes obviously with his uniform.)

“Are you kidding, he wears it to church.” There is nothing secret about this ragging. But during games all the abuse is directed at the opposition. While I was with them, the Seagulls had a relief pitcher they had nicknamed “Psycho,” on the grounds, I was told jokingly, that “he was a potential mass murderer.” As long as he was with the Seagulls his reputed hobbies of killing cats and stalking lizards at night with a baseball bat, crippling them, and blowing them to bits with firecrackers were tolerated uneasily. Now that he has been released, however, should he join an opposing club, he will hear about it from the dugout.

The daily routine of a ballclub that plays seven night games a week is pretty predictable. In Corpus Christi, most of the Seagulls live four to a two-bedroom apartment in the same complex, making home indistinguishable from the McAllen Sheraton. If anything, things are better on the road, since they get $6 a day for food. After the game they drink beer, as often as possible in the company of the young women who flock to the ballparks to meet them. Even in the Lone Star League there are groupies (known as “Baseball Annies”): in a crowd of two hundred, fifty or so will be women who are there to flirt with the players. Retiring anywhere between midnight and dawn, the players sleep until noon or later, then hang around their hotel rooms or apartments watching soap operas or whatever else happens to be on TV until it is time to dress for another game. Sometimes they go to the beach, although they are careful not to get too tired from the sun. What baseball players consider being in good physical condition is laughable compared to other professional athletes, or even serious amateurs, but a few jog or work with weights in the mornings. At $400 a month, a real spree is economically beyond reach, although I heard one starting pitcher brag all the way to the ball park about having been drunk and naked in a swimming pool at five that morning with a girl he had picked up in a bar. Privately, I suspect, most of the team thought him foolish and some may even have been irritated. The only public attitude permissible, though, was to wish that the girl had a friend. Mazzone says that if he were managing for a major league organization or if the team were losing he would impose a curfew, but since each player’s career here is his own affair, he doesn’t see why he should. As in most such groups, there is a whole lot more talk than action.

From a conditioning point of view, the worst thing about the way the Seagulls live is the way they eat. Just before starting a long postgame drive from Harlingen back to Corpus Christi, the team actually voted to dine at a Seven-Eleven rather than stop at a restaurant. Even when you are near broke, you can do better than a six pack and Doritos for supper.

The atmosphere of loose-jointed semi-boredom and hilarity of men in such groups is communicable. Although I had anticipated a good deal of free time and brought along enough books to occupy me for a month, it took only a few hours to realize that reading anything at all that did not either list batting averages or show pictures of naked women would be unthinkable. What I really wanted, of course, was for Leo to look down the bench when Fran Hirschy had a couple of men on and a dangerous stick man coming to the plate and say something to me like: “If you can still throw that knuckle curve you had back in ’61, go loosen up your hose. We need a double-play ball here.” I was not, if it matters here, a bad high school pitcher. But I was never privileged to pitch for a club where if you went in there and coaxed a sharply hit ball to the infield with a man on first, those boys would turn that double play over almost every time and you could go sit down.

Because that is finally what it is all about. What the Corpus Christi Seagulls are is a baseball team, nothing more or less, a thing that requires neither apology nor even explanation. They perform on summer evenings under uncertain lighting, with too much wind usually and too few fans, but when they do it well, which on this team is more often than not, it is a kind of artistry. Spending days and nights with them and watching them play every evening for a week I finally began to understand that the desire to warm up my hose and throw that sinker to get the double play is no more childish or shameful than my invariable wish when I read something that transports me: my God, I wish I’d written that. But I would rather spend two months on the road with the Corpus Christi Seagulls, thank you, than two nights with a troupe of Shakespearean actors. I can remember telling a friend after hanging in suspense along with about half the nation through that incredible sixth game of the 1975 World Series between Boston and Cincinnati—the game that led Pete Rose to say in the locker room that even though his team lost he was proud and moved to have played in it—that watching it had been like reading a Dostoevsky novel. The suspense and the hysteria were overshadowed in the end by pure aesthetics; the fact that who won was of no intrinsic importance in the “real world” was crucial to that feeling.

The last two games I saw the Seagulls play redeemed both messes in McAllen. The first of the two, in Harlingen against the Suns—after pregame nonsense including egg throws between teams of players, a home run hitting contest in which nobody hit a fair ball over the wall, and similar follies—was tight, crisp baseball, the kind of game that turns on points so minor that most casual fans would miss them. If Randy Rima had not held up at second a moment too long to see if a base hit was going to drop, if he had broken for the plate from third the instant an infielder committed himself to second base instead of waiting until the bail was almost there, if Pagnotta had not overslid second after having the base cleanly stolen, if Bratsen had let Rainey’s perfect throw from center field go through to the plate and not cut it off at the mound and relayed it . . . if, if, if. And everybody understands these things so well that nothing has to be said. As Bratsen comes into the dugout after the inning all he has to do is catch Leo’s eye to see if he knows it too. He does. The Seagulls lose the game 3-1. Harlingen has a pretty good club.

The next night in Corpus Christi, after the repast at the Seven-Eleven and the long ride back in the middle of the night, the Seagulls still need to win a game to wrap up the pennant. And Harlingen has driven up to play them head to head, arriving in a superannuated blue-and-white school bus with the motto “Share in Christ’s Love” painted on the side. While we were gone it rained in Corpus Christi and the dugout is flooded. The players take folding chairs from the “box seats” and sit in front; the mosquitoes that breed in there will be active tonight. Driving in uniform to the ball park in the van with cardboard taped over most of the broken windshield, an expired inspection sticker, and his Maryland driver’s license in his pants back at the apartment, Leo gets stopped by a highway patrolman. The trooper says he could take him to jail, but as Leo is in his baseball suit and L. O. has his catcher’s gear in his lap, he gets off with a warning. “You wanted to see the minor leagues,” Leo says to me. “This is it.”

The last time Mando Reyes pitched here in his hometown 2000 fans showed up to see him and he shut out Harlingen on two hits. Tonight is Corpus Christi Caller-Times Night, and any kid who shows up in a shirt with an iron-on Seagulls patch that he clipped from the paper gets in free. Between 1600 and 1700 show up. Mando is not so effective as the last time, and the Seagulls’ fielding is a bit shaky in the first three innings. The first batter reaches base each time. Each time he tries to steal second, and each time L.O. throws him out with a perfect strike. The crowd begins to get involved in the game. In the fourth Bear Bratsen hits a tremendous home run off the scoreboard in left center, and the way the game is going it feels as if that may be enough. But in the sixth Reyes gives up four base hits and two runs, getting out of the inning when Thompson makes a beautiful stop on a hard grounder and Hiller turns it over perfectly for a double play. The runs are the first Reyes has allowed in 25 innings. In the last of the sixth Rainey walks and Bratsen hits one even further than the last. Seagulls 3, Suns 2. On the bench I tell Thompson I am glad to see Bear tying into the ball, since after all I’d heard about his power I had been disappointed to see him limited to high fly balls and ground ball singles in the last week. Thompson reminds me that the difference between a 300-foot fly ball and a 380-foot home run is a matter of a fraction of an inch on the barrel of the bat meeting a moving object.

In the eighth Harlingen puts together a triple and a sacrifice fly to tie the score at 3. Soon Bratsen is at the plate again, with the bases loaded. This time he catches it a little further out front and hits one, he says later, much harder than the other two, but the strong cross-wind that affects balls hit down the right field line holds it in the ball park and it caroms off the wall for a three run double. The score is now 6-3, and if Bratsen’s future in professional baseball is an illusion, which Leo thinks it is not (although he hit poorly in his one year at San Jose in the Class A California League), he has with three swings fed that dream for at least another couple of months. But so what? For the rest of his life Bratsen will remember this as a perfect day. You don’t get many of those.

Before the ninth inning starts, the press box announcer reminds the crowd that the Seagulls are three outs from the pennant, which everyone on the bench regards as a portent of disaster. The Harlingen third base coach tells Leo that leaving Reyes in will cost him the game. Leo responds with something brief and appropriate. Reyes gives up two doubles and a run, but third baseman Rick Buckner takes a one-hop line drive off the forehead and still gets the out at first base and the Seagulls win the pennant.

When I had spoken to him earlier in the week Bobby Flores had talked about his teammates who had no plans, no training, and perhaps no aptitude to do anything but play baseball. With a UT business degree, Flores plans to begin looking seriously for grown-up’s work at the end of the season. Last year at Seguin, he says, he played better than he ever had in his life, but with the Seagulls he starts only intermittently (he is the only second stringer on the roster) and is hitting barely above .200. The others puzzle him. “I guess,” he said, “most of them are too busy worrying about where their next piece of tail is coming from or how to find a nightclub to wonder, ‘Where will I be tomorrow?’ But it’s weird to keep getting paid to play a kid’s game, and unless I’m going someplace . . .” His voice trailed off and he shrugged.

Well, Flores is probably right, of course, from the mature point of view, but even after one week with the championship team in the lowest minor league there is, I can see what keeps them at it. I never made a conscious decision to quit playing baseball and cannot remember where or when I played my last game, but it has been more than thirteen years. Even watching one of the Seagull’s star players alternating tobacco spits into the dirt with nervous pulls at a bottle of Maalox between innings was not enough to deter a powerful wave of nostalgia that hit me when I realized I had to leave the next morning. Before the last Harlingen game I played catch for a few minutes with Randy Rima to help him loosen up his arm. Returning to the bench I was struck for the first time with the realization that I was never going to play this game again. Suddenly I felt much older. I told Leo about it. “You try pitching ten years of pro ball and have somebody tell you that,” he said. Then he spit a stream of tobacco and walked down to see how Mando’s warm-up was coming along.

- More About:

- Sports

- Longreads

- McAllen

- Corpus Christi