This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

When they were feeling masochistic, the underwater archeologists of the Texas Antiquities Committee would thumb through a back issue of National Geographic that was kept on the coffee table in one of the mobile homes where they were quartered last summer. The article they always turned to featured photographs of divers gathering unbroken glass bottles from an ancient Greek shipwreck and swimming them to the surface through the stunning Mediterranean water.

The crew gazed longingly at these photographs, shaking their heads in disbelief or resignation. Life was not fair. Here they were on a remote stretch of the Texas coast, working in shallow, opaque water, rooting blindly in the mud for artifacts that, even should they be found, would be so corroded and encrusted they could be identified only with x-rays and electrolysis.

But these moods did not last long. The crew realized they were at the mercy of history, and history is specific in the fact that three hundred years ago the great explorer Réné-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, had lost two ships—and, as a result, the whole notion of French dominion in the New World—in the deceptively tranquil waters of Matagorda Bay.

The first day I went out with the TAC on their boat, the Anomaly, it seemed we were due for another installment of bad weather, which had been making working conditions even less enviable than usual. There were thunderheads over Pass Cavallo, scudding southwestward down the coast. Under the cloud cover the water of the bay was the color of spoiled meat, yet so strikingly calm that, even with the two engines grinding below and rattling the steel hull, the boat’s passage through the water was as smooth as if it were gliding over a sheet of ice. To the northeast, where we were headed, there was a faint rainbow.

“I see a pot of gold over there,” someone said. “Let’s go find that.”

We were on our way to Green’s Bayou, a small cove cut into the lee side of Matagorda Peninsula where La Salle’s four-gun frigate, the Belle, is believed to have gone down in 1685. On the way out the crew lounged about on the deck in their canvas-and-Velcro UDT slippers. Some of them were asleep, using inflated buoyancy compensators as pillows. Others inspected the peeling skin on their shoulders, or read, or talked together in the verbal shorthand they had developed after a month of close quarters. The crew consisted of nine men and three women, most of whom were in their mid-twenties and were either graduate students who had won a place on the La Salle project on the strength of their résumés, freelance archeologists doing contract work, or outright employees of the TAC. They were friendly, efficient, generally sedate people, though in rowdier moments some of them were not above dropping their cutoffs and mooning the Anomaly from the inflatable Laros boat used to ferry crew members back and forth from the land-based transponder stations.

This was a practice that Barto Arnold regarded indulgently. As the state marine archeologist, he had enough to worry about without seeing to it that his crew members kept their pants up. A mild-looking, thirtyish man, he had the air of a kindly teacher supervising a school picnic. He spent most of the working day in the cabin of the Anomaly, where he worked trig functions on a clipboard or monitored gamma hits on a digital readout. Arnold seemed to take comfort in gadgetry and calculations, not simply because they were his only means of following a trail that had been cold for three hundred years, but because they satisfied some key component of his personality in the same way the headstrong forays into the wilderness had satisfied La Salle’s more intense and troubled spirit. La Salle’s character came down through the centuries clear and intact. He was an obsessed, intractable man who nurtured all his adult life a private vision of the conquest of the Mississippi River. He was all but insensible to hunger, pain, and monotony and did not seem to understand that other people were affected by these things. His imagination, which was vivid, operated only in a very narrow range, and in the end his failure to sympathize with the tribulations of his followers was perhaps the predominant factor that led to his eventual murder at their hands.

Barto Arnold was also a private man, but he was a different sort of explorer. He was as cool and precise as an astronaut, and one imagined his taking as much pride in the orderliness of his search as in its fulfillment.

I stood over the diving platform at the Anomaly‘s stern and looked back toward Port O’Connor, which we had just left. In my imagination I removed the town from the horizon and picked up the channel markers in the bay and the stock tanks on the peninsula. What was left, I decided, was what La Salle had seen in 1685 as he and his fleet lay anchored outside the pass and he was busy convincing himself that this bare, alien landscape, with its labyrinthine network of bays and lagoons, was the western mouth of the Mississippi.

La Salle had everything riding on that supposition. He was 42 years old and had been preparing for this moment all his life. He had reached the Mississippi—his “Fatal River,” as Henri Joutel, who chronicled La Salle’s last voyage, termed it—several years earlier and had descended it all the way to its mouth, the first European to do so. He had called the country he passed through Louisiana, in honor of the King of France, under whose aegis La Salle had now returned by sea to establish a colony at the mouth of the river. The colony would assure French control of the major artery of the New World and put them within striking distance of the Spanish mines and settlements to the west.

But this landscape I gazed out on was not the Mississippi. La Salle and his pilots had overcompensated for the eastward currents of the Gulf and had drifted far westward instead. Since the explorer had been unable to fix the longitude of the river on his first visit, he had to rely on the known latitude and on his visual memory of a coastline that more often than not was so inconspicuous it simply melded into the horizon. The fate of his colony and of the fortunes of New France rested upon La Salle’s dead reckoning, which was dead wrong.

His odd contingent of inexperienced soldiers, families, unmarried women, priests, and dilettantes must have looked upon that drab vista through an already chronic veil of homesickness. The voyage had been bad enough—two months on the open sea without enough water or deck space, one of their four ships lost to Spanish pirates, their ranks thinned by desertion and disease during landfall in Santo Domingo. But these misfortunes were nothing compared to the atrocities that awaited them on these barrier islands and marshes.

Almost immediately their storeship, the Aimable, ran aground as they tried to bring it through the treacherous waters of the pass to safe anchorage in the bay. Their flagship sailed away for France. They found themselves at war with the Karankawas, a violent, unstable people who smeared their bodies with alligator grease and believed that their grisliest nightmares had to be enacted in their waking lives, which did not make them pleasant neighbors.

La Salle, who soon realized he was nowhere near the Mississippi, had his colonists build a fort further inland, on Garcitas Creek near the mouth of Lavaca Bay. With pitiful industry they went about this task, dying from dysentery at the rate of five or six a day. They planted crops and observed feast days while La Salle made one great sortie after another in search of his river. Then the Belle, which carried the last of the provisions for the colony and their only hope of any release from it, was lost in Matagorda Bay. On his third odyssey La Salle was killed by his own men near the Neches River, and the few surviving occupants of Fort St. Louis did not outlive him long. A Spanish expedition that had been sent to dislodge the colony found it soon after the Karankawas had overrun it. The fort was in ruins, its grounds littered with books and manuscripts and the ransacked contents of its houses and with human skeletons, one of which was still clothed in a dress.

Barto Arnold and his crew knew this story by heart. They regarded it with a certain reverence. Like primitive hunters who ritually take on the qualities of their prey, the archeologists seemed to have absorbed some vestige of the colony’s ordeal into their own beings. Perhaps the fact that they were covering the same ground, had endured in some mild degree the tedium, exposure, delays, and disappointments that had crippled the spirits of La Salle’s people made them receptive to the notion that they were the colonists’ historical heirs. In any case, it was not mere professional pride that motivated them. They were a little haunted.

This attitude was most apparent in Warren Lynn, the project field manager. He was slightly older than the rest of the crew and had a wary, purposeful demeanor that suggested he had some private stake in finding the ships.

“I think we’re going to find the Belle today,” he drawled. “I feel good about this spot.”

On board the Anomaly there was a great deal of gadgetry—a magnetometer to sense the presence of metal objects buried in an overburden of mud beneath the bay, a machine called a Mini-Ranger that worked in conjunction with two land-based transponders to transcribe the locations of these objects—which were called anomalies—into Universal Transverse Mercator coordinates, and an on-board computer that used the coordinates to plot a course to a specific anomaly. That, in theory, was the way things were supposed to work. More often than not the transponders were not functioning, and it was necessary to fall back on Arnold’s trigonometry and on optical surveying instruments called theodolites to find the anomaly.

On paper it all looked very precise. The few survivors of La Salle’s enterprise and the Spanish explorers who had come upon its remains had left behind a series of maps that were specific about the locations of the wrecks and, despite three hundred years of wave and wind action, almost identical to the area fishing maps that were sold in Port O’Connor.

But it is one thing to mark an X on a well-defined inlet on a map and another to find that X in the real world. The search areas were vast stretches of water that, to the uninitiated, had no reference points at all, and a magnetometer scan by helicopter earlier in the season had come up with at least forty separate anomalies in Green’s Bayou and in Pass Cavallo. Strong isolated readings were likely to be forty-gallon drums or lost anchors, and most of these could be dismissed, but the rest had to be checked out. In the three weeks the archeologists had been actively digging they had located a nineteenth-century sailing ship, a twentieth-century steamship, and a shell mound embedded with pieces of pipe and old tires, but no Aimable and no Belle.

Time was running out. Arnold and his crew had only another five or six weeks to find the ships, and the Texas Historical Commission, which funds the TAC, was starting to crowd in just a little, wanting to make sure it got a return on its money.

It happens that Texas is one of the few states that have given financial support to underwater archeology. This situation is the result of the discovery of a fleet of Spanish ships that sank off Padre Island in 1554, loaded with gold and silver bullion and other treasures from New Spain. The ships were originally located by a private salvage firm in 1967, but the state took an interest, formed the TAC to recover the find, and tied the original discoverers up in a litigation process that has still not ended. In 1972 and 1973 the TAC, whose crew included Barto Arnold, chief archeologist Carl Clausen, and a dozen or so assistants, recovered the artifacts from the Spanish fleet, a major piece of archeology that is the basis of a museum exhibit currently touring the state. Though the find had left Arnold’s program relatively well endowed, the budget left no time for leisurely, thorough fieldwork. He and his crew were expected to move in, find something flashy, and get it before the public eye.

By the time the Anomaly reached Green’s Bayou, the sky had cleared and the shallow water of the bay was an appealing pale green. The peninsula was about a hundred yards off, and I could see across its low dunes to the surf on the far side. Small islands, irregularly shaped and so plush with dune grass they reminded me of carpet remnants, fanned out from the lee shore.

The dive site had been marked the day before with buoys, and all that was necessary to pinpoint the anomaly was for one of the crew to swim a magnetometer sensor around until Arnold saw the gamma count jump on his readout. That done, the boat was anchored so that the starboard prop was directly above the anomaly.

The visibility underwater was good for Matagorda Bay—two or three feet—but clarity would be a moot point once the prop deflector (named Linda, for Linda Lovelace) began blowing out a hole in the mud bottom of the bay. Over the centuries the metal parts of the sunken ship—all that was likely to be left of it—would have sunk beneath an overburden of mud and clay and shell, which would have to be cleared away in order for any artifacts to be revealed.

Linda looked like a gigantic pop sculpture of a piece of elbow macaroni. It was lowered by a pulley over the stern and fitted over the port prop by two divers, who bolted it to the hull. Over the open end of the blower they slipped a small net to guard against the unlikely possibility that a diver, despite the downward force generated by the moving propellor, might swim up into the tube and be spat back out in little pieces.

When Linda was in place, the Anomaly’s port engine was turned on, rattling the boat again and spoiling the midmorning stillness. Linda deflected the power of the spinning prop and sent it down to the bottom of the bay, where it began gouging out a hole. A great pallid mass of overburden rose from the bottom and spread out over the surface, clouding the green water.

Rock Richardson and Bill Crow, the two divers who had attached the deflector to the hull, were the first team to go down. They sat on the diving platform checking their equipment as Jim Zeisler, the divemaster, logged the time of their descent. As they slipped off the platform, one of the crew began a modified football cheer. “Find that . . . artifact! Find that . . . artifact!”

The engine was kept running while the divers were down, both to expose new ground and to insure that a diver working in a hole eight or ten feet deep would not be buried in a sudden mud slide.

“When I’m down in the hole,’’ Peggy Leshikar told me as we waited for the divers to come up, “and I feel a clump of something hit me, I always stand up just to check things out. I don’t much want to become an underwater anomaly.”

Leshikar was a veteran of several diving projects and an employee of the TAC. Her background was in drama, and it showed in the way she handled herself in the close quarters of fieldwork, which is so reminiscent of the fervent, short-term bonding characteristic of theater troupes. She lent an air of gravity and sisterly forbearance to the open flirtation that had evolved as a basic form of communication between the sexes.

Crow surfaced twenty minutes later, pulled his mask up onto his forehead, and spat out salt water.

“Okay,” he reported to Arnold, “the walls are almost vertical. It’s like a tin can. No shell hash at all. Visibility is good—Rock and I can see each other if we touch masks. There’s still a lot of sand, though. You’re going to have to blow it out some more.”

Arnold signaled for more power to the prop. The cloud at the surface immediately grew denser and more agitated. Crow repositioned his mask and went down again. The rest of the crew started digging their bologna sandwiches out of the cooler.

I recalled what I knew about the circumstances of the loss of the Belle. During his second foray from Fort St. Louis in search of the Mississippi, La Salle had left the Belle anchored some distance from shore on the other side of the bay. When its crew began to run critically short of water, they sent a boat out to replenish the supply. The boat never returned, and the crew was now left with no means of getting to shore and nothing to drink except wine and brandy, an extremity that may have encouraged them in their decision to sail the Belle, which was now seriously undermanned, into Lavaca Bay and up Garcitas Creek to Fort St. Louis. As they were getting underway a violent north wind drove them across Matagorda Bay and up against the peninsula. Six of the men built a raft out of parts of the damaged ship, but all of them drowned when the raft came apart as they tried to cross the bay. The rest were luckier. The boat originally sent out for water was found washed up on the beach, driven there by the same squall that had foundered the Belle. The survivors paddled to safety, doing La Salle the favor of taking along some of the private papers and possessions he had stored for safekeeping aboard the ship, but leaving the Belle itself, with the greater part of the colony’s tools and ammunition, and its last chance for survival, to settle into the mud at the bottom of the bay.

Crow and Richardson, after an hour’s work underwater, had found nothing to explain the anomaly that the magnetometer had picked up. They climbed out of the water and oozed mud onto the deck. Two more divers went down and came up an hour later without results. Jim Zeisler and I were the next team.

“Now you’ll be able to see what it’s like to dive in a washing machine,’’ Arnold told me.

“Yeah,” I said, trying to work myself into the mood. I pulled on my weightbelt, which was alarmingly heavy—maybe 25 pounds. But I was assured I would need that much weight to prevent me from being blown out of the hole by Linda.

“It’s really not so bad,” Peggy Leshikar said. “You just have to keep reminding yourself that no matter what’s going on if you just stay calm you can make it back to the surface.”

I was not quite reassured and made a point of attaching my mask by a lanyard to the collar of my buoyancy compensator in case it got blown off.

“We’ll go down holding hands,” Zeisler said. I noticed all at once that he looked a little like my conception of La Salle, a lithe man with wavy shoulder-length hair. “There’s a chain at the center of the blower. We’ll hang onto that for a while and then swim around the circumference of the hole.”

We slid off the platform into the cloudy water and joined hands just below the surface. Zeisler’s gardening glove, disembodied in the murk, seemed suddenly like the hand of a spirit guide, drawing me down into a region I was not sure I wanted to enter.

It was a strange passage. We had descended only five or six feet when a curtain of darkness closed across my face with such swiftness that I wondered if I had lost consciousness. To test the visibility I pressed my hand against the glass of my mask. I could not see my fingers.

Down another few feet I felt the turbulence from the blower. I had been warned this would be strong, but nobody had suggested I would be encountering a hurricane ten feet underwater. In total darkness we swam against the steady pressure Linda put out against us. The water-wind howled all around us and began to pry the mask from my face. With my free hand I held it down and fought my way against the current. When it seemed impossible to go any farther, as if the slightest loss of mental concentration or muscular tension would send my body shooting out of the hole into an underwater void, Zeisler let go of my hand and wrapped it around the weighted chain that fell plumb from the center of the blower. I hung on, allowing my body to slide down the chain to the bottom of the hole, and then loosened, just a bit, the tight rein I had been keeping on my imagination. There was a moment of panic, which I found quite understandable, and then an unexpected charge of serenity.

Zeisler took my hand off the chain and we began our tour of the circumference of the hole. I followed along tranquilly, drugged by the strangeness, wondering how it was possible for the archeologist to get any work done down here at all. I had no sense of up or down, much less of lateral direction, and knew only intellectually that we were making a circle. When I felt more in control, I let go of Zeisler’s hand and let myself sink into the cool mud and wallow there like a flounder, feeling casually for artifacts. Blind, weightless, able to hear nothing but the incessant roar of the blower, I felt very close to the events that had brought me here, as if the three hundred years between the loss of the Belle and my groping for its wreckage had been effaced, and I was about to encounter something more vital than corroded crucifixes and harquebus parts.

The crew dug three separate holes that day, yet found no objects to explain the anomaly.

“It’s going to be another one of those question marks,” Arnold conceded. “That happens about ten per cent of the time.”

It was almost 7 p.m. by the time the Anomaly returned to its slip in Port O’Connor, and it took the crew another hour to hose down all the diving equipment with fresh water, carry it into a dockside shed and square away the boat for the night.

Field headquarters for the archeologists in Port O’Connor consisted of two large mobile homes in the Lotsa’ Luck trailer park. The crew was generally a little grumpy about the accommodations, especially since they had to pay for them out of their own salaries, and for the $100 or so a month they each paid for one-sixth of the living space of a mobile home they could have rented larger houses in town. But Arnold wanted them all in one place. The logistics of the project were complicated enough without having his crew scattered all over town.

Port O’Connor is a fishing village, especially during certain summer weekends when sport-fishing tournaments are held for purses as high as $60,000. At such times the two cafes in Port O’Connor—whose menus are so identical one suspects the cooks of shuttling back and forth between them—are crowded each morning before dawn with anglers in gimme caps advertising machine shops or bait stands. The high-rent contenders have breakfast in their condominiums or on their fishing boats, whose gleaming white fiberglass cabins rise in tiers above the waterline and look vaguely confectionary, like wedding cakes.

Things quiet down during the week, when the town’s chief inhabitants—shrimpers, offshore oil rig workers, a few stray millionaires—reassert themselves. One can catch The Bad News Bears Go to Japan at the Jamison Theatre (whose name has been amended by vandals to read I M N Heat) or watch kingfish being filleted at the bait stand or swim off the scruffy Intracoastal beach.

The TAC crew had settled easily into the rhythm of life in Port O’Connor. After dinner Barto Arnold pulled up to his desk and began making calculations, Jim Zeisler went down to the shed to take apart all the regulators that had been used that day and were therefore clogged with mud, a few people left to get beer, and others assumed meditative postures on the ground outside the trailer and stayed there as long as the sunset lingered over the bare stretch of coastal prairie behind the Lotsa’ Luck.

The rest of the crew stayed inside, washing dishes, writing letters, or discussing diving in the hole, of which they had grown perversely fond. They decided it should be thought of as a sport of its own, like ice or cave diving.

The walls of the trailer in which we were sitting were hung with USGS maps of Matagorda Bay and caricatures of crew members drawn by Ed Aiken, the staff artist. Various malfunctioning electronic devices, diving equipment, buckets of fossils and bottles and Civil War artifacts the archeologists had picked up along the beach crowded the floor space of the mobile home.

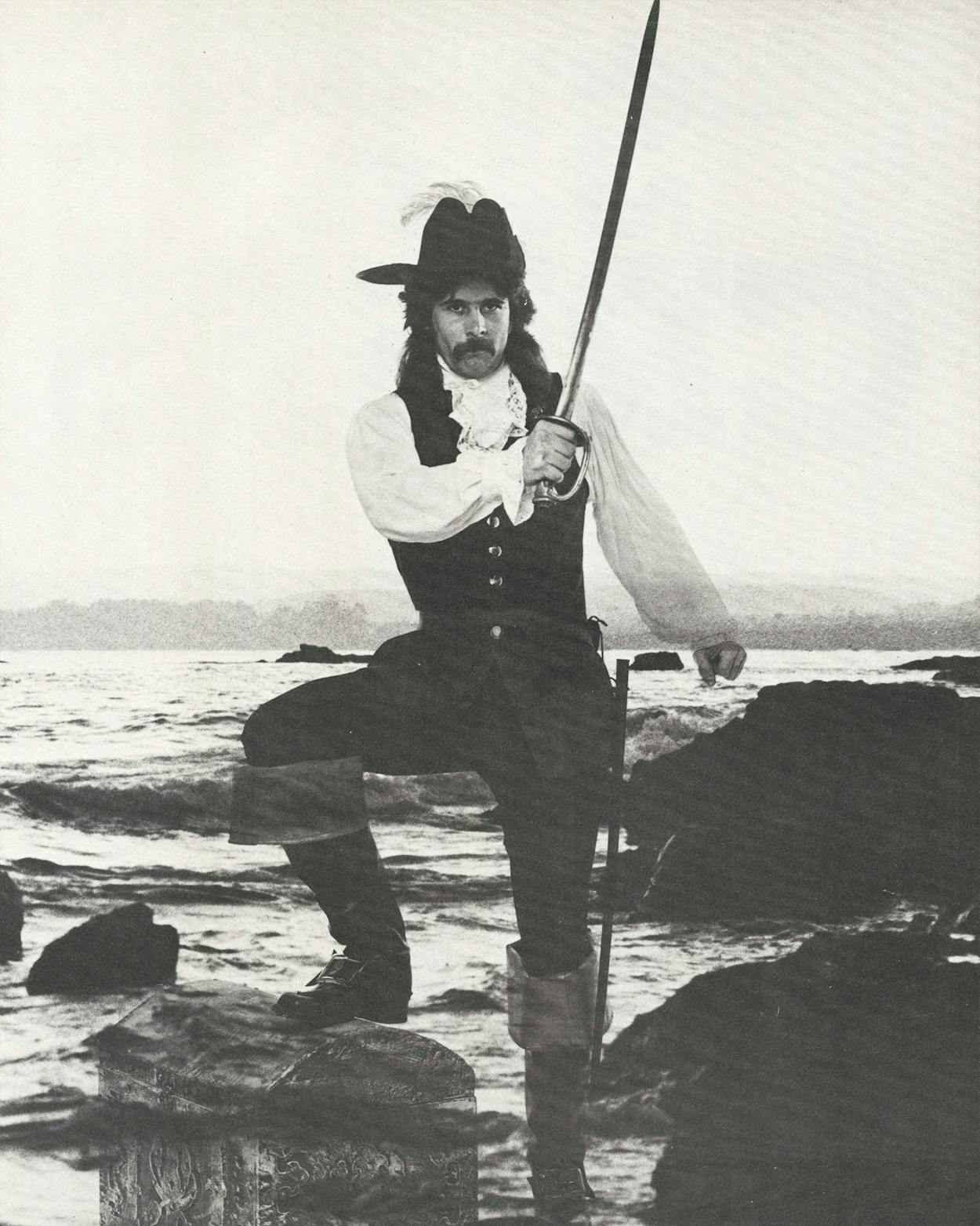

“Can you believe that these guys actually walked around here dressed like that?” Warren Lynn asked, handing me an edition of Joutel’s narrative I had not seen before. He pointed to a frontispiece illustration, “The Sieur de la Salle Unhappily Assassinated,” in which the murderers, foppishly attired in lace and stockings and powdered wigs, were standing about in various courtly postures with La Salle’s corpse at their feet.

The real event, of course, would have been grislier. In his final march from Fort St. Louis, La Salle and his men had been wearing canvas clothes cut from the sails of their lost ships. It was a desperate journey. With the ships gone, La Salle knew he not only had to find the Mississippi; he also had to ascend it all the way to the Illinois and from there work his way up to the Great Lakes and down the St. Lawrence to Quebec, from which he could send word to France of the plight of the colonists left behind at Fort St. Louis. In his extremity, La Salle characteristically picked up the pace, leading his men on with a remorseless drive that merely intensified their anarchistic inclinations. One night, some distance from the main camp, La Salle’s nephew, his Shawnee guide, and another man loyal to La Salle were hatcheted to death in their sleep by mutineers following a bitter dispute over the distribution of the marrow bones of a buffalo that had been killed that day. When La Salle came looking for his nephew they shot him in the head from ambush, stripped his body, and kicked it into the brush. Half the murderers went off to live with the Indians; the others joined with the shocked remnant of La Salle’s party (among whom was Joutel, the source for most of this information) in an uneasy alliance that held together during the near-miraculous journey to Quebec.

Meanwhile the twenty colonists left at Fort St. Louis—mostly women and children and Récollet friars—held on to their miserable hope of rescue.

On my second trip to the coast I brought a canoe, planning to paddle along Garcitas Creek past the site of Fort St. Louis. There was nothing left of the fort, and the owner of the land where it had been located consistently denied access to those few La Salle freaks who asked permission from time to time to look for the site. But I knew from Joutel’s memoirs that the fort had been built on a hill on the south bank overlooking the creek some two miles from the mouth of the bay.

Garcitas Creek was as wide as a medium-sized river and heavily trafficked by power boats. I put in at a highway bridge and paddled downstream in consort with water skiers and bass fishermen until, after about a mile, the outboard noise receded and there was a primitive silence enhanced by the frequent surface splashing of bass. The surrounding land was coastal plain, but at the banks of the creek the foliage was dense and tangled.

“We were . . . on a little Hillock,” Joutel wrote, “whence we discovered vast and beautiful Plains, extending very far to the Westward, all level and full of Greens, which afford Pasture to an infinite Number of Beeves and Other Creatures.”

A high bluff on the south bank of the creek seemed to fit Joutel’s description of the site of Fort St. Louis, and I decided I would believe that that was where it had been.

What could it have been like there three hundred years ago? I imagined the colonists walking about on that bluff, numbed by nostalgia and despair, the children playing under armed guard in a nearby cleared field, the men and women fruitlessly tilling crops and tending the livestock, the priests setting out with Joutel in their tattered cassocks to learn the art of hunting “beeves.”

The glowering coastal beauty—the startling sunsets over the plains, the wildflowers, and the immense flocks of shorebirds—must have lulled them occasionally, but likely these things made them feel even more bereft after two years of menace and boredom and constant, wearying privation.

Joutel, who commanded the fort while La Salle was gone on his first two journeys, kept the dispirited colonists busy hunting or shoring up defenses. He even performed a marriage between one of the gentlemen and an unattached woman, but these moments of ceremonial gaiety must have been rare. The Karankawas hovered around the stockade, sniped at hunting parties, and their presence was only the most obvious danger the French settlement faced in this strange world. Lives were lost to rattlesnakes and to alligators, and the colonists were terribly afraid of “a venomous creature, which we suppos’d to be a Sort of Toad, having four Feet, the Top of his Back sharp and very hard, with a little Tail.”

At that last Christmas mass before La Salle left on his final journey, the remaining colonists must have been undone with hopelessness and fear. They probably begged him to stay, feeling the need of his personality, which, as harsh and self-absorbed as it was, compelled them and gave them focus. He was going to Canada! He might as well have been going to the moon.

Past the site of the fort the land flattened into marsh. The banks were clear now, inhabited by exotic and healthy-looking cattle and egrets who stalked about at their feet. The creek split into channels before it entered the bay, and the main channel became a canal lined with vacation homes and private docks.

I stashed the canoe at the Lotsa’ Luck, where a reception was being held for the board of directors of the Texas Historical Commission. They had come down for a firsthand look at the project they were sponsoring, and the next day they would follow the Anomaly out to Green’s Bayou in a rented boat to watch the divers work. This evening the crew popped popcorn for them and put on a slide show. Arnold stood in front of the screen, with his hands deep in the baggy utility pockets of his pants, and provided a commentary.

“We’re looking forward to finding both the Belle and the Aimable by the end of the summer,’’ he ventured.

The next time I went out on the Anomaly we headed into Pass Cavallo in search of the Aimable, the big storeship that had broken apart on the shoals and gone down with four cannons, 1620 cannonballs, 400 grenades, 4000 pounds of iron, 5000 pounds of lead, tools, and a forge.

La Salle had been inland, negotiating with the Karankawas for the return of some of his men they had taken prisoner, when the Aimable ran aground in the pass, the pilot apparently ignoring the deep-water channel La Salle had painstakingly researched and marked. As the explorer was treating with the Indians he heard a cannon shot, the signal for disaster, and looked back toward the pass, one supposes, with a sinking heart. He could see the sails of the Aimable furling on the horizon.

Some of the contents of the ship were salvaged, but in the night a wind came up and split its hull, so that a great deal of the colony’s essential stores were lost.

Since it was unwise for the Anomaly to enter the dangerous waters of the pass from the bay we went up the peninsula a few miles and entered the Gulf through a man-made cut. There was a light rain and medium swells, and the landmarks that had looked so conspicuous on the maps once again proved to be abstractions.

Hopes were high. The anomaly we were going to check out was promising, a series of isolated readings that were spaced out in a manner that suggested the strewn debris of a wrecked ship. The crew bustled around the deck, ignoring the rain and the increasingly high seas.

Inside the pass the water was just as rough and stippled everywhere with whitecaps breaking over shoals.

Arnold sat in front of his gamma display as Warren Lynn drove the Anomaly, which was trailing the mag sensor. A four hundred gamma hit appeared on the readout.

“Gee whiz!” Arnold said. He had the crew drop a buoy.

“That could be the sixteen hundred cannonballs from the Aimable,” he reflected, “or it could be Joe Garcia’s shrimpboat from three years ago.”

A twenty-gamma reading.

“Just a little tickle that time,” Arnold said, then he suddenly yelled “Mark!” when another four-hundred-gamma reading appeared.

“I’ve just got a feeling about this one,” Lynn said.

The boat was anchored, and in the rough water it took four divers to bolt Linda onto the hull. Zeisler and a crew member named Manny Montoro went down first, and Montoro was not down five minutes when he surfaced, pulled the regulator out of his mouth, and yelled, “All right!” He and Zeisler had found a metal object about five feet long still half-imbedded in the mud. He said he thought it was a cannon. Zeisler brought up a fragment of wood.

“It looks like plywood,” Peggy Leshikar said, “in which case it’d be too recent. Wait a minute. I think I read somewhere the Romans had plywood.”

“We found a Roman galley,” Arnold announced mockingly. He decided to make a personal inspection and went to his private stash of diving gear. He had a custom wetsuit, a stabilizing jacket, and a squeeze bottle of liquid defogger to use on his mask instead of spit.

He was underwater a long time. When he came up he sat on the diving platform for a while without speaking.

“You want to know what’s down there?” he said finally. “A goddam piece of railroad iron!”

Nineteenth-century garbage. I went down to see it anyway. The visibility was not bad—even in the center of the hole I could see two or three inches ahead. I held my mask close to the submerged rail and ran my gloved hand over the barnacles that covered it.

In the middle of August a few days before the season was over, the crew investigated another anomaly in the pass that looked exceptionally promising. They dug all day on it and probed down through forty feet of overburden, but whatever objects were down there still eluded them. The only way to dig deep enough would be to rent a dredge, an extravagance the TAC could not afford.

I drove down for what was supposed to be the last day of diving, but the transmission in the Anomaly had gone out, so the season had come to an uninspired close. A television crew came down to film the archeologists at work, and with the Anomaly out of action they had to fake the whole thing with the boat still tied to the slip. Artifacts found from the other wrecks were planted in the waist-deep water, and a diver crouched below the waterline and then “surfaced,” waving the treasure over his head.

Now that the diving was over, the few days remaining in the season were devoted to simple drudgery. The crew went soberly about their work, bitter at not being able to explore the anomaly in the pass that they seemed to believe, with one mind, was the wreckage of the Aimable. I also felt a mild shock at seeing the crew, which had been such a tight organic unit, begin to unravel.

“I really hate not finding it,” Manny Montoro said, scraping barnacles off the bottom of the overturned Laros with his diving knife. “It would have been so nice to return home in triumph.”

He looked up at Warren Lynn, who was also working on the Laros.

“If we’d found the ships,” he asked, “would that have been like, you know, a really major discovery?”

Lynn pried off a barnacle and answered without looking up, “Hell, yes.”

I was feeling guilty about not helping them scrape barnacles so I walked off a little way and looked out toward the pass, thinking that La Salle himself could not have been much farther away than this when he turned back and saw the Aimable, bearing his ballast and ordnance and twenty years of unfulfilled dreams, run aground on the shoals.

There was talk about coming back in the fall with still more gadgetry, with an experimental subbottom profiler that would provide a schematic picture of the components of that final, tantalizing anomaly. Perhaps if they could get enough funding, the archeologists could come back the next summer and find the wrecks. For now they had to take what comfort they could in knowing they had done their best and maybe sensing, in their failure, a more intimate correspondence with a living history than its physical evidence could have provided.

In Austin a few days later, a half-dozen members of the crew got together and decided, despite the anticlimax and disappointment, to celebrate the end of the season. They ate chicken-fried steak at a restaurant and went to a disco, which bored them. They shouted over the dull, feverish music, making plans for a trip to Cozumel, a diving trip to clear, calm waters.

Out on the dance floor a few couples were posturing beneath the strobe light, watching themselves in the full-length mirrors surrounding them. Someone at our table proposed a toast to La Salle. The setting for such a toast could not have been more discordant. I felt the overburden of three hundred years of history, and remembered those moments, down in the hole, when I had felt very close not just to the artifacts I imagined were all around me but to the source of the power they held over my imagination. Now it was all silting in, and there seemed no better way to invoke the memory than to raise my glass. To La Salle.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads