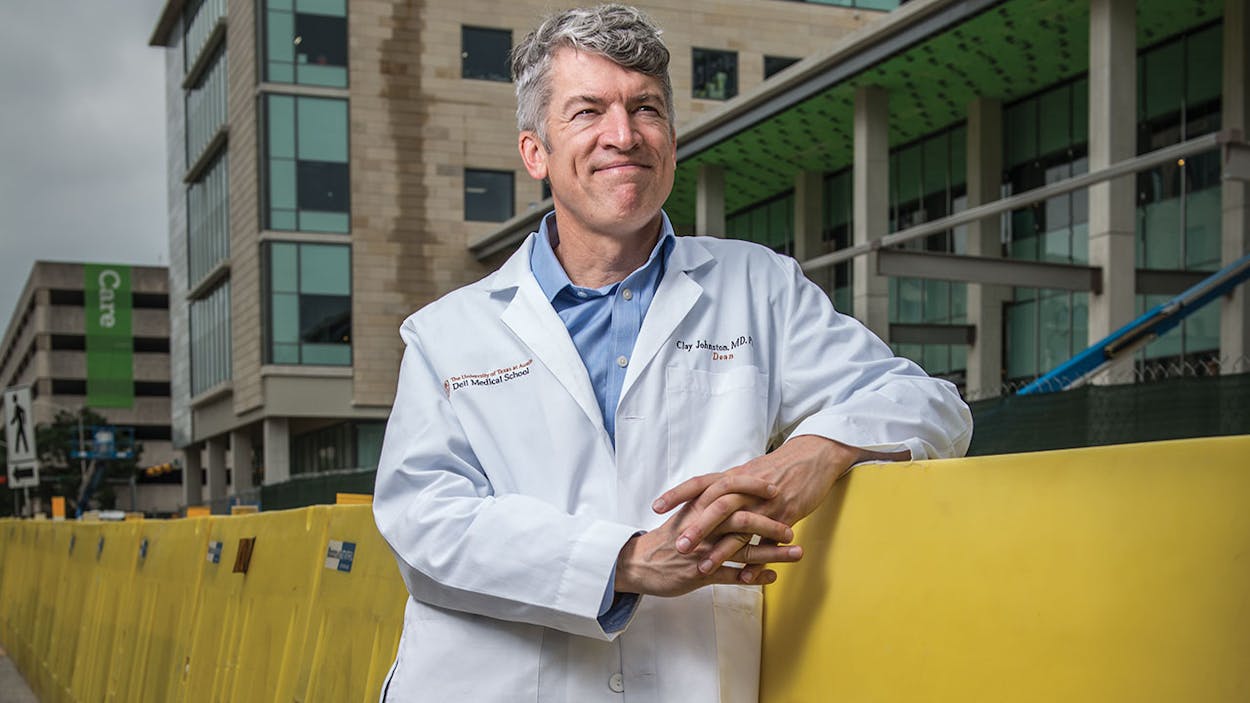

In June construction on the primary teaching building of Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin was completed. Even before it opened, Dell—the first medical school to be built at a Tier One American university in more than half a century—had received a great deal of attention from the media for its innovative curriculum and focus on Austin’s underserved communities. As the school prepared for its inaugural class of fifty students, its dean, S. Claiborne “Clay” Johnston, the former associate vice chancellor of research at the University of California, San Francisco, sat down to discuss what makes Dell so unusual.

Jeff Salamon: The inaugural class of students shows up in about a month. What’s taking up most of your time and bandwidth right now?

Clay Johnston: The students, not so much. A lot of work went into recruiting this class—the interviews and all of that. But that’s all done. The curriculum is done. There are details that need to get worked out, but that’s easily doable in the short term. The things that are top of my mind now have to do with the services that we provide. Typically that’s clinical services, but for us it’s really health services. It’s not just things that happen in the clinics and hospitals, it’s the way in which we bring this community forward and improve the health in the community. All of that needs to be up and running as soon as possible. Right now the schedule is for the construction of our clinic building to be done about a year and a quarter from now. We want that to be humming from early on.

JS: One thing that’s gotten a lot of attention is that the school is shaving a year off the traditional two-year science curriculum and allowing students to engage in more-focused study. What’s the thinking there?

CJ: It’s about how we create physicians as leaders, physicians who can focus on trying to change our health care system. It starts with the recognition that the system is horribly broken. There are lots of ways you can demonstrate that, from the obvious things of not being able to email a doctor—emails are ubiquitous in every other industry and you can’t use it in health care. Or the fact that our health care costs are substantially greater than those of any other country’s. Our health care costs are now almost $3 trillion, and the estimate is at least a third of the cost is waste. That’s $1 trillion that we’re wasting. Our health care outcomes are similar to those of Cuba, and Cuba spends about an eleventh of what we do on health and health care. So then the question becomes, Why haven’t we fixed it? And, What is the role for academic medicine in fixing it? How can we restructure the way we train, the way we provide services, and our research to be better aligned with society’s interests in health? And then we make that real by saying we need a place in which to demonstrate how to do it better. That’s where we get to Austin as a model healthy city. How does it become a model for other cities, and how do we become a model for other academic medical centers?

JS: How do you cut an entire year from the standard science curriculum? Is a lot of the usual medical school curriculum a waste?

CJ: Our curriculum is a little different in that students don’t get their summers off, so it’s a little unfair to do a year-by-year comparison. Our years are basically ten and a half months instead of nine months. Still, science is the foundation for medicine. But there’s a lot of stuff in the curriculum that isn’t relevant to the practice of medicine. It’s almost more of a rite of passage.

JS: Can you give me an example?

CJ: There’s this thing called the Krebs cycle—I’ve never used it since my memorization of it, which is, of course, gone. A childhood geneticist who treats patients with abnormalities in the Krebs cycle—okay, they should know it. But for the rest of us, it’s just been in the curriculum because that was one of the few things we knew about biochemistry fifty years ago. There are many, many examples like that.

The other thing we can do is, it used to be that memorization was a doctor’s best bet to have access to information when you’re caring for patients. Now, if your memory is not very reliable, if you really don’t know something, you can look it up and it takes about a second to do that. Whereas it was much harder to do that previously. So it’s more important that we teach people what they don’t know—how to look up things, how to synthesize information—and then use that to make better decisions about diagnosis and treatments for patients. So we can change our curriculum up, it doesn’t have to be lecture-focused and memorization-focused, like traditional medical school curricula, like the one I went through. It can be problem-focused. And, yes, the students need the core basic knowledge of science, about the way diseases manifest, all of that. But they can learn in recorded short lectures or through some readings that they do at home.

The other realization that is not really reflected in most curricula is that physicians generally do not practice alone; they generally practice best when they’re working in teams. And it’s not just teams with other physicians, it’s teams of other kinds of practitioners. It could be a nurse or a pharmacist or a social worker. So we can start to get them thinking and understanding the value of working in teams better: don’t rely on yourself as the individual, traditional Marcus Welby, M.D., out there on your own. You will be much more effective if you are integrated into a system and into a team and you know your strengths and you’re not so cocky as to think you know everything.

JS: Obviously, to become a medical school you had to be accredited. How skeptical were the accreditation boards?

CJ: Well, there’s two. The LCME [Liaison Committee on Medical Education] has been interested in more-innovative approaches to medical education and has tried to push schools to think about what skill sets we want to teach students and to adapt their curricula to that. In addition, the American Medical Association has been saying, Why are our curricula so one hundred years ago? It’s basically built on a framework that was created one hundred years ago. Why aren’t we innovating? The AMA created a consortium of institutions working on moving education forward, which we are a part of. So those institutions want change. It’s the individual medical schools that are having trouble producing that change.

JS: To the best of your knowledge are there any other schools pushing as hard as you guys in terms of curriculum innovation?

CJ: Not as far as us, because that’s the advantage of starting from scratch. But there are a number of other schools with interesting components of their curriculum and several are reorganizing their curricula right now. Harvard just announced a curriculum that does some of the same things ours does. It reduces the basic sciences, for example. Utah is working at redoing its curriculum. UCSF just redid its curriculum. So there are a number of places that are doing it. Kaiser is staring a new med school too. We don’t know much about it, it was just announced maybe 6 or 9 months ago. My guess is it will do some of the same sort of thinking we have.

JS: Texas seems to be on something of a medical school building boom. El Paso opened a school in 2009, the UT–Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine is scheduled to open in July, and Texas Christian University and the University of North Texas plan to open a school in 2018. Do you talk with those institutions?

CJ: Rio Grand Valley, that’s a great group and we’re thrilled to help them where we can and vice versa. We love that they’re doing what they’re doing. The other two planned schools, we’ve talked to their leaders, we’ve shared everything that we can share, which is everything, with them. We’re hopeful for their success as well.

JS: When Michael DeBakey took over Baylor College of Medicine, in Houston, his philosophy was that medical school should be like the Army: it should be an extreme experience, and doctors should learn to perform under any conditions. Does that square with your philosophy?

CJ: [Laughs.] No. Medical school is an extreme condition regardless. Think of what we’re putting students—young adults— through. They go from being students, where it’s all about them—How do you gain more knowledge? How do we make you a stronger person and make you better and more successful in your future—to, okay, now it’s about caring for others. Your whole career, your whole satisfaction in life becomes how successful you are at caring for others. You don’t know anything about what you’re doing, no matter how much scientific training you’ve had; you do not know what it means to care for patients or populations. And if you make a mistake, it could have dire consequences in real life or death terms for someone. Now, of course, we protect our med students from that. They should never be in a position where a mistake that they make has life or death consequences. So that doesn’t happen anymore. But that definitely happened when I was in med school. And it definitely did in DeBakey’s version of Baylor.

The other stress is that every student that gets into medical school is at the top of their class; otherwise they wouldn’t get in. All of a sudden, half of them are below average. That’s devastating to this hyper-overachieving group. That is a real shock to the ego as well. So you take these people who have been the center of attention and the pinnacle to realizing that they’re nothing basically in this new world. You don’t need to apply further pressure to encourage them to learn as much as possible. In fact, what you need to do is to support them. Suicide and depression rates among medical students are really high. Why would you do something to make that even higher?

For us, it’s almost the opposite. We have to support these students, and it has to be a really intense experience—it would be anyways—but what we really want to do here is to say, okay its not just about the traditional role of the doctor. You do have to do that, you have to be a great clinician and care for patients. But it’s more than that. If you’re here, we expect you to identify the systemic problems. Not just what happens in a transactional visit, but what’s happening in health care in the world, and identify those problems and help to address and find solutions for them. So it is a big, creative challenge that we’re putting in front of them. They should all be entrepreneurs, they should all be ready to step up and be leaders. It doesn’t mean they’re going to start businesses, that’s not what I mean by entrepreneurs. They need to be creative, find solutions, and be able to guide those solutions through the system.

JS: The novelty of your approach doesn’t seem to have scared off students. When you were taking the first applications for admission, I think you predicted you would get maybe 2,000 applications; someone else on your team predicted 3,000. And you wound up with 4,500 applications. For fifty spots. I don’t know anything about medical school admissions. Is that an unusually high ratio?

CJ: Yes.

JS: That’s a yield of about 1.1 percent. How on earth do you make decisions on who to take? You took fifty kids. My guess is the next four hundred must’ve been just as good as the first fifty.

CJ: Absolutely. Late in the process we had to pull somebody up off of the waiting list—this was the last person that we pulled off of the waiting list. And he was the first kid in his family to go to college, from South Texas, raised by his mom, four other siblings. Had a 4.0 GPA. Super kid. And he had had a spot at UT Southwestern, which he gave up in order to come. So we are not having any problems recruiting super folks. He was an interesting one because he had spent some time teaching between graduating from college and applying to med school. So he’d been teaching in an underserved area in Texas.

That’s a very typical story for the kinds of students that we got. Austin is a great city for students. UT is a fun institution to be a part of and has great depth in so many different areas. So that shouldn’t be underestimated, the impact of those things. But also we are really different and the students see that and they get excited about it. They feel our excitement about what we’re trying to achieve and the caliber of faculty that we’ve been able to recruit, and they want to be a part of it. Some of it could also be the appeal of the new, right? The shiny new device. I hope that very little of it is that. We’ll find out next year whether we continue to do as well in recruitment, but we certainly did very well this year.

JS: Does such a large number of applicants put stress on the admissions system?

CJ: UT is accustomed to admissions systems that include massive numbers of applicants, so we learned from them. We were able to interview fewer than 10 percent of the applicants. That’s the real stress, that was hard, and there’s gonna be some arbitrariness. And there’s arbitrariness once you interview people, too—how they did that day or who they interviewed with.

One of the things we’re considering is a very short pop interview question. It’s been tested out in some schools where, by cell phone, you send somebody a question and you give them a few minutes to prepare, and then they video tape their response and they have a minute to respond. But it gives you at least some sense of them, how do they communicate, how do they address a question. That provides another factor that we know is ultimately important in whether we select a student. The communication skills and their commitment, their passion, all of that is really critical and very difficult to assess from a written application.

JS: Any sense of how much of the incoming class is from Texas?

CJ: Ninety percent.

JS: Wow.

CJ: We’re required by the legislation to have 90 percent of the class be from Texas.

JS: Oh, okay. Any idea what percent of the applicants were from Texas?

CJ: It was about 75 percent. There were about one thousand applications from people out of state for five positions. From out of state it was almost impossible to get in.

JS: The school’s teaching hospital, which is still under construction, will pretty much overlook I-35, which has been the traditional dividing line that has kept people of color and poor people separate from the rest of the city. You’re reaching out to those communities—you’re setting up clinics on the East Side, you’ve partnered with Huston-Tillotson, the historically black college. Whose idea was that?

CJ: It was the community’s idea. When Proposition 1 [which helped fund the school] came to a vote, one of the key messages that led to its passage was about providing new models of care, particularly for the underserved. Overall, health in Austin is pretty darn good by state standards and even by national standards. But the disparities and inequities in health outcomes are too great. Austin still has a substantial population living in poverty and that is, more often, the African-American and Hispanic populations. So we have to focus on that if we’re going to make Austin a model healthy city. And it’s not just for altruistic reasons, although that is enough. There are plenty of economic reasons to solve this problem as well. When we don’t actually focus on how to improve health upstream, the costs to society, which we’re bearing one way or another, are substantially greater. So the costs of dealing with the complications of diabetes are much greater than the cost of proven programs that substantially reduce the risks of diabetes upstream. That’s the kind of work we think is critical to any community, but Austin is actually a great environment in which to test these models.

JS: It’s usually very difficult to get doctors to do indigent care, because it’s not very remunerative.

CJ: The students certainly know that that is a critical part of our mission, and we’ll have a large number who are committed to that. We think it’s really about, How do we produce the models that value the impact that one can have in that population as much as in an insured population? To us, fundamentally, that is a much more important problem and one that we are trying to position ourselves to address.

JS: The disparities in Austin are pretty dire, from the statistics I’ve seen. There’s a five-year difference in terms of life expectancy between women in the wealthiest quartile in Austin and the poorest quartile. Among men, it’s nine years. Many people on the East Side lead lives of economic precarity, which often leads to poor health outcomes. But a teaching hospital can’t, on its own, address those sorts of deep-seated issues. Do you see it as part of the school’s goal to reach out to politicians or nonprofits to address those issues?

CJ: In everything we do, we want to figure out how we can enable other entities to address health problems. There are a variety of different entities out there. Some are already doing work in that space, and there are some that are well positioned to but don’t know how. One of the key fundamental problems in this is, How do we acknowledge that if we don’t invest today, we have to pay much more downstream, and the consequences are worse? How do we create those new business models that let anyone with a solution succeed? And not rely on philanthropy and not rely on the small residuals of government that get left over and put into public health entities? If one just examines it pragmatically as a business person, one can see that avoiding having to pay huge amounts in acute care, taking some of that avoided waste and moving it upstream to prevent that illness, benefits everyone, including taxpayers. That’s what we’re trying to do, create that framework. It’s really a platform play. What we’re trying to do is create a platform. So just like, if you had a BlackBerry and it had five functions and they were all produced by BlackBerry and they met most of your goals, that was fine. But as soon as Apple turned the iPhone into a platform, where any developer could create an app, there was just a whole array of different needs that could be addressed and a whole host of people who were offering solutions. And if those tools were successful, somebody would pay for them. There was a whole new marketplace for it. That’s the kind of platform that is missing in the health care system. Innovations have been dead in the health care system for years. We have a lot of innovation that we call research, but it doesn’t get translated into scalable, sustainable improvements in health. What we’re trying to do is say, okay, what’s necessary to create a platform like the iPhone for health innovations?

There are a few things we know we need to do. One is economic models; there couldn’t be anything more important than that. How do you get people paid based on the outcomes they have, the health outcomes that we all value in society, and the economic impact of those health outcomes? The second is, we have to have data. We have to be able to know that this intervention produced this change. So we need a much richer data system than we currently have. It’ll take years to develop the ideal data system. We actually have a lot of data today. We just need to integrate it better and use it effectively to actually pay for return on investment.

The other is, we need connections. If a person comes from a poor area in East Austin and knows how he can get his community to care about their blood pressure, how can health providers enable that person, who understands their community? How do we enable them to be successful in doing that? That requires expertise in the science, in the clinical areas, in economic models, and then a team needs to be created around those ideas. For example, with digital health, an entrepreneur, usually kids, software engineers, they come up with an idea. Well, they don’t know how the health care system works, so are they producing something that’s actually useful? Could it be employed? They don’t know that. But creating a team around them, the ones who do have potential have a greater likelihood of producing success.

That’s what the other pieces of the platform are. That’s our big play, that’s what we’re trying to do. It’ll take a decade to do all that. And we can do some of that today. So then the question becomes, for the short term, how do we organize ourselves so that we’re best able to deliver and provide the most value in a health ecosystem that’s focused on society’s interest in health? And that becomes the organizing force for us. And then we need to make money from this stuff. Because our people are expensive. And the other participants need to make money from it too. So how do we also create the economic models that make it sustainable for all the partners?

JS: So you’re mostly talking about the private sector?

CJ: Public and private. Some of the support that we’re getting early on is from foundations. They want to see the system of health care flipped and know that we’re gonna need to make investments now in order to see that happen. The reason you don’t see a place like Johns Hopkins or UCSF, where I came from, doing this, is, why would they? They’re making a ton of money in the current fee-for-service system, so they’re not motivated to do this at all. So again, it’s our unique position that allows us to say, it’s not about us bringing in a lot of money to keep our docs and MRI machines going and ORs busy, it’s about our entire structure and how that supports moving society’s interests in health forward.

The reason health care is where it is, is it’s a failure of innovation. Tech is a good example. Tech has totally transformed the banking industry, media, entertainment, but tech has been on the sidelines and if anything has made health care less friendly. You know, when you go to see your doctor and the doctor is facing the monitor while they type—why is that? It’s complicated why, but it’s a failure of innovation.

JS: It’s not just a failure of innovation. One of the reasons we have worse health outcomes than other developed countries is because we tend to have higher rates of poverty. Isn’t there a deeper, systemic reason?

CJ: That’s a great question. That’s true for some countries, like Scandinavia. But Cuba is at the very same level in terms of health outcomes as us. And again, they spend a fraction of what we do on health care. Of course the sociologists will tell you, “Well, then it’s about inequities, right?” And for sure, inequities produce stress and strains and are associated with worse health outcomes. But they exist in other countries without the same impact. England is another great example. The English system now produces the best health outcomes of the developed world. Well, they have the same social inequity issues that we have. So, these are solvable. But I don’t think that “big P” health-policy changes are going to be the answer in the U.S.

JS: What is “big P”?

CJ: Not little policies on a local level, but national health policies. Obamacare has been so polarizing that nobody is going to do anything substantial that moves the national system forward. Given that, we have to ask, What is uniquely American? What is a special part of being Texan? Part of that is looking for free-market solutions, entrepreneurial solutions, and being driven by capitalism to address our concerns. We’re trying to create a system that uses the same techniques of entrepreneurialism that have been successful across our economy to address the health needs of the community. It’s apolitical. It should be apolitical. It’s not about redistribution. If we engaged in redistribution, could we improve health? That’s not a question I’m going to answer, and it’s certainly not one that the school is going to push forward. On the other hand, can we, with better ideas, hard work, and embracing technology and new systems of care, address a lot of the needs of the health care system? Absolutely we can.

We’ve shown we can do that in every other sector. It’s just a matter of how we create the system in which to do that.

JS: It’s interesting. The two countries you cited as having great health outcomes—Cuba and England—both have national health systems. You wrote an article for the Alcalde, UT’s alumni magazine, about “Ten Backward Things About Our Health Care System.” And you talked about tech, you talked about how everyone hates those gowns that open in the back, and you talk about the fact that we pay for procedures rather than outcomes. One thing I couldn’t help but notice is that you stayed completely away from the debate that the nation is actually having right now, which we’ve arguably been having since the Clinton administration, over what sort of health insurance we should have. Is that too much of a third rail for the dean of a new medical school to touch?

CJ: I would say it a different way. The issues are so polarizing that if you declare a position, people stop listening and looking for the common ground and a potentially workable solution. I think what we’re focused on at Dell is a potentially workable solution that embraces what is unique and a great strength of America and of Texas and should satisfy the political spectrum. So that’s the reason I choose not to take a position on that. It is true that those two countries have national systems. I will tell you that neither of those systems would work in America. You’re less likely to get cancer in Cuba than here. But if you have cancer in Cuba and it’s far along, your outcomes are not going to be great. They’d be better here. And though England’s National Health Service has become more person-centered over time, initially it created barriers that would have been unacceptable to us in the U.S. So I don’t think any country has the solution. Also, those systems have been really slow to innovate. The NHS has had every lever and bit of control and it’s just now implementing a national health record. That, to me, suggests that they’re missing some of the ingredients, some of the things that we do particularly well in the States.

JS: The third leg of Dell’s mission is the research. I know that you want to look throughout the university for ideas, even outside of the medical school. What are we talking about here? Pharmacological research? Medical procedures? Platforms and iPhone apps and ways to reach out?

CJ: The whole gamut. For us, there’s tremendous opportunity to find new solutions to problems in health through interdisciplinary mechanisms. Anybody in a single discipline loses sight of creative responses that are possible by opening your eyes up to other areas of focus. So, yes, we will partner with the College of Natural Sciences, they’ve got some fabulous departments—the chemistry department, for example, is one of the best in the world. Engineering is also really interesting. They’re doing a lot of things that one would typically think of as health care, like devices and heart monitoring and that kind of thing. But they’re also doing some things related to data organization and how to bring complex data together and how to analyze data that’s highly relevant to us. And monitoring issues—things that get you into digital health.

But the first institute we created was with the College of Fine Arts, and that was the Design Institute for Health, which is a collaboration between our two schools. We hired a couple guys from IDEO, the [global design firm] that created the computer mouse. One was the head of their health care practice, the other was the head of complex system design. And they co-direct the Institute and that is a fabulous thing. They’re looking into how our clinics are organized, how a department is organized, how the school itself is organized. They’re able to create a way of approaching those problems that’s unique, that’s more likely to yield better solutions.

JS: I’m trying to grasp this, because I’ve read a little about these folks. Are they designing physical spaces, or organizational flow charts?

CJ: All of it. They are actually designing our clinics—our health transformation building, we call it. One challenge there is to eliminate the waiting room. That was one of the challenges they were given. But it’s really about flow: how does somebody know where to go, and when? And how do we know where the patient is, so we know if they’re running late? And how do we coordinate the visits? And then what is their experience like? And how do we eliminate that horrible waiting room experience, of getting coughed on and seeing other sick people, and them overhearing conversations and all that. And the out-of-date magazines? How do we turn it into something that is not a negative? For one thing, how do we make it so that it is not 40 minutes, which is the average wait now? Those are the kinds of things they’re doing. The communications school, too, we’re doing a lot with them. Business, law, the LBJ school, we’re starting to plan some work with them. So there are tremendous opportunities across the university.

JS: You’ve gone from one city, San Francisco, which has a vibrant cultural scene, a booming tech sector, and soaring real estate values, and you’ve come to another city, Austin, with a vibrant cultural scene, a booming tech sector, and soaring real estate values. Have you been surprised by any commonalities or differences?

CJ: Austin is a little less transient than San Francisco. People in San Francisco aren’t there for as long; people in Austin tend to stay. The sense of community is different. San Francisco has a series of small communities and they each care for themselves. Families are not a big part of San Francisco, they tend to move out; it’s a hard place to raise kids. Whereas here there are still separate communities each taking care of themselves, but there’s more interlacing of those communities. And its much more family-friendly.

The issues about affordability and demographic shifts are only just beginning here. In San Francisco it’s been going on for longer and it is far more severe. San Francisco’s approach to growth has been, slow it down. That has led to even greater housing costs and greater disparities; all the teachers have moved out of San Fran because it’s just not affordable. Austin is more about growth and central density as a solution. That’s a very different attitude.