This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The power center of the Pentagon is not its center at all but its rim: a mile-long corridor known as the E-Ring, which forms the perimeter of the huge building that is home to the Department of Defense. My office when I served as an assistant secretary of the Navy from 1984 to early 1988 was on the E-Ring, along which passed the major figures of the nation’s defense establishment, bound for meetings in places with mysterious names, like the Tank and the Blue Room. There were also couples in shorts pushing strollers, high school band members wearing jackets with clef signs, and Japanese grandmothers—all taking the free public tour of the most sensitive department of American government. Every few minutes during the peak summer season I would hear the parade-ground voices of the young enlisted guides boom, “This is the Navy and Marine Corps recruiting-poster collection. These posters go all the way back to 1863.”

The spiel grated on me, not so much for the volume as for the error I knew it contained: The collection included a poster dating from 1777. One day I stopped a guide and pointed it out to him. He was shocked into wordlessness, but the system moved quickly to correct the mistake. Someone removed the 1777 poster.

The poster incident demonstrates the typical lot of a political appointee in the Pentagon. You can get results, but you can’t be sure of getting the result you want or even one that makes sense to the nonmilitary mind. And though you can get a quick response to an inquiry about posters, just try to find out why sailors spend fifteen weeks at an expensive training school instead of twelve: “Well, these things take time, sir, and why do you want to know?” I had covered politics as a reporter for the Houston Chronicle, I had been a member of the Texas Legislature, and I had worked in the White House, but nothing I learned about government quite prepared me for the Pentagon.

Even John F. Lehman, Jr., the secretary of the Navy from 1981 to 1987 and one of the most powerful and effective men ever to head one of the military departments, experienced the same frustration. He likened it to being a child in the kiddie seat of a car, hands on a little plastic steering wheel, bouncing merrily along, turning the wheel this way and that—but going only in the direction that Mom or Dad wants to take the car.

Franklin D. Roosevelt, no slouch at bureaucratic politics himself, served as assistant secretary of the Navy during World War I, when that job was number two in a Cabinet-level department. (By the time I held the same title after seven decades of governmental growth, due in no small part to FDR, it was tied for third in a sub-Cabinet department.) “The Treasury and the State Department put together are nothing as compared with the Na-a-vy,” observed President Roosevelt in 1940, after learning of something the admirals had done only by reading about it in the press. “To change anything in the Na-a-vy is like punching a feather bed. You punch it with your right, and you punch it with your left until you are finally exhausted, and then you find the damn bed just as it was before you started punching.”

In the United States there is an honored tradition of civilian control over the military. We owe this blessing not to the Constitution, which says nothing directly about civilians running the armed forces, but to the precedent set by George Washington, who chose to serve as president in the eighteenth-century equivalent of the pin-striped suit and not in the leggings and laces of the triumphant general of the Revolutionary Army. The career military no doubt has been disgruntled, puzzled, or simply amused with the situation for two centuries now, and their game—played long before there was a Pentagon—is how to get around the civilian potentates placed in temporary authority over them. American military officers, especially in the senior ranks, may grumble about the dunderheadedness or meddling by these bosses and constantly devise schemes to test, distract, beguile, or thwart them. But this bureaucratic warfare, not actual warfare, is what a political appointee is paid to wage and win.

The civilian leaders of the services are not part of the combat chain of command. Our function is to ensure that the armed forces are well equipped and ready for the uniformed military to deploy. My job as one of six presidential appointees in the Department of the Navy was to oversee everything that affected people—recruiting, training, pay, benefits, health, housing, discipline, women’s and minority issues—for 600,000 Navy and 200,000 Marine Corps men and women and their families, as well as retirees and more than 300,000 civilian employees in everything from shipyards to laboratories. All those things carried a price tag of $35 billion a year, chiefly in payrolls. (In view of later events, I am grateful my job had nothing to do with procurement.)

One can admire military people for their courage, loyalty, skill, and character—as I do—and still not be comfortable 100 percent of the time with their judgment, especially on nonmilitary matters. This is when the civilian appointee can provide the most help to the service he helps lead: giving the sympathetic but independent point of view that comes from having been in the world beyond the barracks. It almost doesn’t matter what that background might be—business, politics, the law, or whatever—so long as the appointee retains a sense of balance and proportion and the willingness to step in and say, “Whoa,” when the career folks are about to do something that will cause them needless grief in the press or in Congress.

Last year I was at a briefing on a new cruise missile. The briefer, a naval captain, described how the missile would be tested: It would be fired out of a submarine’s torpedo tube, break to the surface of the water, and fly over the northern reaches of Maine. Everything about the program was impressively researched, generously funded, and blessed by the entire chain of command right up to the highest levels of the uniformed Navy. But something had been overlooked. I raised my hand, and the briefer stopped in surprise.

“Yes, Mr. Secretary?”

“I don’t pretend to know how your missiles work, Captain,” I said, “but I do know something about politics. Your scheduled date to announce the test is one week before the New Hampshire primary. You send your bird whizzing around the woods in Maine, and over the border, the next president of the United States may get pressured into promising to cancel your whole program.”

The room erupted in gasps and exclamations from a covey of admirals, who vowed to delay announcing the test. Alas, it was announced right on schedule—the kiddie seat bounces again!—but fortunately the horde in New Hampshire somehow didn’t pick up on the issue.

It is not enough for a civilian executive in the Pentagon merely to oversee or to react. Often it’s essential to push the system to do even things that the system itself admits needs to be done but has classified as too hard. Times like those—whether trying to nurse naval medicine back to health or to get Navy recruiting commercials on the air in a sufficient number to keep America’s teenagers from thinking that the only way to be all that they can be is in the Army—were when I would encounter another horror of the military bureaucracy: the tyranny of the filing cabinets.

One difference between the Defense Department and the other government agencies is, obviously, that military people are at their desks for only two or three years before being transferred to another assignment, usually far away. Instead, then, of the crusty old bureaucrats who have been around since the Fair Deal and will be around long after the political appointees have left, there are the crusty old file folders, each one bearing the invisible stamp, “The Way We’ve Always Done It.” The Navy is perhaps the most traditional of all the services. Not until recent times was the zipper authorized for the flies of sailors’ trousers, in place of the little buttons that always seemed to multiply in a man’s moment of distress (or opportunity). And if the buttoned fly was good enough back in the War of 1812, then so, too, runs the logic, are the health-care and recruiting policies that you recklessly propose to change.

When the burdens of bureaucracy get too troubling, there is always the happy escape called visiting the troops. Aside from providing a needed break, getting out to the field or to sea serves as a reminder of why you go to work every day in the five-sided building. Out where the ships and planes and tanks are is where the national defense exists, not in the plush briefing rooms of Washington. Although there is the inevitable tendency of your host to put the best face on everything, the truth is easier to find out on the briny blue. It comes in casual conversations with a blunt-talking gunner’s mate at chow or a frustrated junior officer late at night on the bridge.

There is, however, a danger in going out to the fleet, and that is of building a reputation as a trip taker or junketeer. (A verbal war I waged at Navy was getting people to not call these ventures “boondoggles.” A boondoggle is a needless public-works project; a needless publicly funded trip is a junket. Got that? I suppose the mistake arises from the old military slang word “boondocks” or “the boonies,” which comes not from the Vietnam War but from an earlier American jungle war, namely the taking over of the Philippines from 1899 to 1901. “Bundok” is the Tagalog word for “the jungle” or “the outback.”)

Unfortunately, taking junkets is what many military officers expect of the civilian politicos who float into and out of their lives. Whether their aim is the benign one of teaching the visitor about the capability of their weapons and people or the malign one of getting the old boy out of the Pentagon the week some big decision has to be made, those admirals and generals can’t resist singing the junketeer’s siren song: “When are you going to come see us in Pearl, Mr. Secretary?” or “You haven’t been yet, sir, to see an exercise in the North Sea.”

In my four years at the Pentagon, I never took a foreign trip; that qualified me for either a medal or a psychiatric examination. There were many reasons for this. In response to the protest that it’s important to get out and visit the troops, I replied that there are plenty of troops to visit along the 865-mile line between Washington and Orlando, where the Navy and Marine Corps do everything they do anywhere else in the world. Also, I remembered that when I was an aide to an admiral in the Philippines during the Vietnam War, we were constantly visited by self-imagined potentates from the Potomac, whom we had to go greet at the airport at midnight on a Saturday, while pretending to be oh-so-happy for the honor and opportunity.

But the major reason I never went abroad was Pentagon realpolitik. A political appointee’s duties are bureaucratic, not operational. In government you don’t worry so much about what isn’t happening when you’re away as about what is happening without you. One particular incident comes to mind. On a Friday morning in May 1986, I was in my office reading clippings from around the naval world. A small article from a Norfolk newspaper said that the Navy was going to stop giving dependents free over-the-counter drugs. That meant no more cough syrup for Junior or aspirin for Mama. The impact on the morale of Navy and Marine families would have been devastating and could have been the final reason why a top sailor or Marine wouldn’t reenlist the next time around. No one had run the proposal by me or anyone else in the Navy secretariat; the medico-admirals had just decided on their own to do it as a cost-cutting measure. In short order, we got the foolish policy canceled and word put out to the fleet. Crisis averted.

Now, suppose on that Friday morning I had been on board the nuclear-powered carrier Enterprise somewhere in the North Arabian Sea. After watching the mesmerizing takeoff and recovery of jet aircraft, I would have taken a helicopter out to one of the “small boys” (destroyers and frigates) escorting the carrier. Upon arrival I would have received the traditional greeting by a double row of eight “sideboys,” or sailors, saluting me while a boatswain’s mate “piped me aboard.” Passing through the cordon, I would have been greeted by the captain, toured the ship, had lunch on the “mess decks” with the sailors, met with the chief petty officers, and discussed current naval events with the officers in the wardroom.

All that would have made for a memorable day. But 10,000 miles away in the Pentagon, the buy-your-own-damn-Tylenol policy would have been implemented unchecked. I wouldn’t have found out about it until weeks later, when angry letters would come in from Congress or from some of the very sailors I had met at sea, who had received angry letters of their own from wives home in California with sick kids.

Even without leaving home, a political appointee in the Pentagon is treated about as regally as anyone in town. Unlike a newcomer at the White House, who has to go through a silly struggle to wrest his share of perks, a Pentagonian pooh-bah knows in advance what perquisites he (and his successor) will get. This includes having high-ranking military officers (in my case, a naval captain and a Marine colonel) as personal aides—a matter of no little irony to me, recalling the year I spent as an aide to a two-star admiral. Those assignments are prized as excellent jumping-off places for promotion to “flag” (admiral or general)—which means a political appointee has a pick of the highest-quality officers. And there is the parking place right at the door, while thousands of other beings have to park somewhere in one of the vast lots that surround the building or trek in by bus, subway, or car pool.

Then there is the matter of the Pentagon itself. Built at the start of U.S. involvement in World War II, it is still the world’s largest office building. Amazingly for a place so huge, the Pentagon is hard to see from across the river, in the Washington tourists know best. It hunkers down on a swamp between Arlington National Cemetery and National Airport and doesn’t appear until you are just about to reach it by road. Everything is in fives: five sides, five rings, five stories above ground, and five stories below. And in the center is a five-acre courtyard with magnolias and other flowering trees. Pentagonians who spend lazy lunch hours during the warmer months in this pleasant park call it Ground Zero.

Inside the building are 17 miles of corridors and 29 acres of offices containing 16,000 lighting fixtures, 4,200 clocks, more than 7,700 windows, and 284 rest rooms. The notion in last year’s thriller No Way Out that a room-to-room search of the Pentagon could be conducted in an afternoon is ludicrous, at least not without the aid of the Third Army.

Although there are five sides to the Pentagon, only two have any cachet: the River Entrance, where the secretary of defense, the secretary of the Air Force, and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff are, and the Mall Entrance, where the chiefs of the Army and Navy are located. The Pentagon also has five concentric rings, of which only the outside one—or the E-Ring—matters. But it isn’t enough simply to be on the E-Ring of the Mall or River entrances. Oh, no. You have to have an even-numbered office—denoting the outside of the building—to get views of the real world outside, instead of merely more windows on the drab, prisonlike interior rings. My own vista extended from the Custis-Lee Mansion beyond Arlington Cemetery, across to the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. And as for the windows themselves, once again rank determines everything: Presidential appointees get three, the equivalent in social envy to a free country club membership in business. Genuine insiders in the Department of Defense can tell more about an official’s importance from his room number than from his title.

Those of us in long-established outfits like the Navy have our prime spots and will never lose them. But pity the new assistant secretaries of defense for this-and-that recently created by Congress.

Jim Webb, a novelist and Vietnam War hero who later succeeded Lehman as the Secretary of the Navy, served in one of those new positions with an office far from the choice territory. “The good news is that I’m on the E-Ring,” Webb told me one day early in his tenure. “The bad news is that I have a view of the Dempster-Dumpster.”

One aspect of my job that some might regard as a perk was greeting foreign dignitaries. Whenever a defense minister, prime minister, or other foreign panjandrum visits the Pentagon, an arrival ceremony takes place on a grassy area in front of the River Entrance. There are honor guard units from all five military services, masses of flags, music by one of the service bands, and nineteen-gun salutes. After all that ends, the secretary of defense leads the visitor down from the reviewing stand to shake hands with a line of officials, including a secretary whose sole duty is to stand at attention during the salutes and anthems and to smile while shaking hands afterward. This is known as being a potted palm, and the duty is rotated among the various assistant secretaries. I did it on the average of once a month. In that way, I met such luminaries as Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Great Britain, Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, and repeated defense ministers from Belgium. I’m not quite sure what effect a handshake from me had on those innocent Belgians, but shortly after they returned home, their governments would fall, and over would come a new defense minister to be met (and doomed) by Untermeyer. My motto soon became, “I greet ’em; they defeat ’em.”

Another sort of assignment brought me the greatest notoriety I was to enjoy as an assistant secretary of the Navy (that is, if you forget the time the Washington Post falsely reported that Fawn Hall had become my secretary). Secretary Lehman put me in charge of the process by which he selected new ports for the scores of ships he persuaded Congress to buy. Among those was the World War II battleship Wisconsin, to be refitted and located somewhere along the Gulf Coast in the early nineties. It was a wild time for about a year: Mayors, governors, and port directors practically lined up to get through my door; I was treated to crawfish lunches and Chinese dinners; I was made an honorary commissioner of Mobile County; and at every moment all those Mississippians, Louisianians, Alabamians, and Floridians suspected that in the end I would carry on in the tradition of Lyndon Johnson as a Texan in Washington and do a little something nice for the old home state. A lot of folks are convinced that Untermeyer’s Texas roots had something to do with Corpus Christi’s winning the Wisconsin. This is not true, but I’m sure not ever again going to get free étouffée from the people in Lake Charles or be allowed back in Mobile to claim my commissionership.

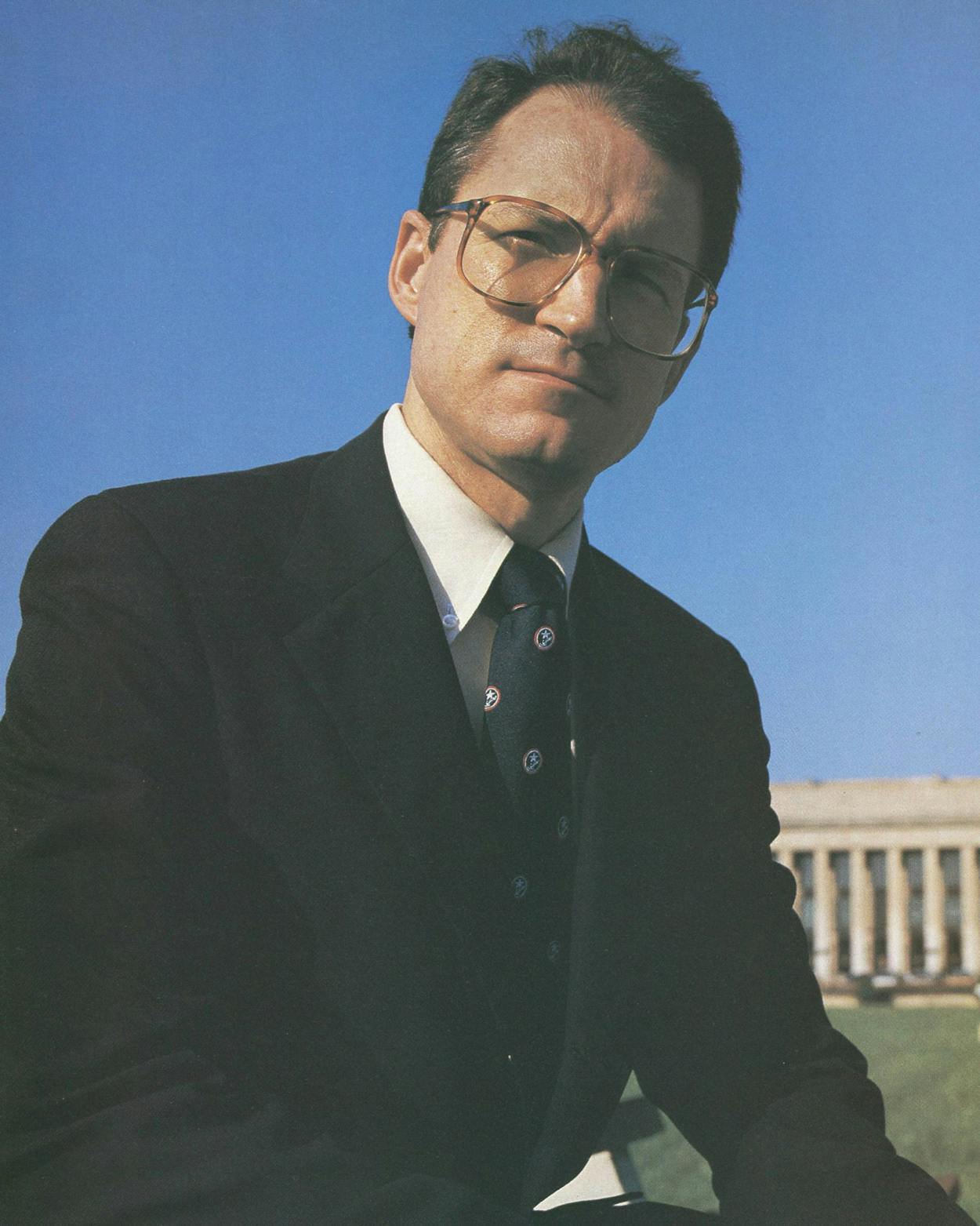

Chase Untermeyer is currently with George Bush’s campaign in Washington, D. C.

Pentagon Patter

The Defense Department is famous (or infamous) for its own peculiar argot, with acronyms like CINCUSNAVEUR (pronounced “Sink Us Never,” it stands for Commander in Chief of U.S Naval Forces in Europe) and CINCSOC (“Sink Sock,” the Commander in Chief of the Special Operations Command). Here is how to speak Pentagonese like a native. Unsurprisingly for a place that spends almost $300 billion a year, most of the terms concern money:

THE POM: What the acronym means (“program objectives memorandum”) is less important than what it is, which is a military service’s wish list or proposed budget. A weapons system or a runway that is on the list is said to be “pommed.”

GOLD WATCH: A spending program offered up as a voluntary budget cut when the offerer knows the program is so important or politically popular that it can’t possibly be cut—for example, the Navy’s proposal to give up a Trident submarine, the most secure part of the nation’s strategic defense. In civilian Washington, this is called the Washington Monument gambit, in honor of the legendary time the Interior Department offered to close the obelisk as a budget-cutting ploy.

PET ROCK: A spending program dear to the heart of a service or a magnate in the Pentagon or Congress. “Oh, don’t cut that; it’s the chairman’s pet rock!”

RECLAMA: A pseudo-Latin word meaning “protest” (noun and verb). If someone’s pet rock is left out of the POM, he’s sure to reclama.

THE TANK: The room deep within the Pentagon where the Joint Chiefs of Staff meet. When a service chief is late and his aide explains that he’s “still in the Tank,” it doesn’t mean he’s out for a long drive over rough terrain or that he’s shriveling up in some hot tub.

DOWNSTAIRS: In the Pentagon the secretary of the Navy (SecNav) is on the fourth floor and the secretary of defense (SecDef) is on the third floor. When Navy people talk of “sending the POM downstairs,” they mean submitting their budget request to the secretary of defense’s staff. That is the only sanctioned use of the landlubber’s word; elsewhere, at sea or ashore, proper sailors say “below.”

HACKENSACK: Not the town in New Jersey but the collective name for the House and Senate appropriations committees (the HAC and SAC). On the authorization side of things is the Hask & Sask, which isn’t the name of a pub in Belfast but the House and Senate armed services committees. C.U.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Military

- Longreads