On the day John Holmes Jenkins died, he was searching for a grave.

Finding the final resting place of James B. Burleson, a forgotten figure from early Texas history, would have been a big score for Jenkins. He’d searched plenty of times before, because he believed that uncovering the grave could provide a missing piece to a book he’d been writing for years. It would be the first biography of Edward Burleson, a frontier fighter who’d led troops during the earliest conflict of the Texas Revolution—the Siege of Bexar—and the last—the Battle of San Jacinto. Edward was also James’s son. Jenkins felt the Burleson legacy had unjustly waned over the course of the twentieth century, and what’s more, Jenkins’s great-grandfather had been raised by Edward. He believed the story was his to tell.

Jenkins asked his cousin, a young Episcopal priest named Ken Kesselus, to come with him that day and canoe a stretch of the Colorado River, about ten miles north of Bastrop, to look for the grave. Kesselus had canoed with Jenkins before, and the last time they were on the Colorado, a violent thunderstorm had roared out of the sky, terrifying Kesselus. After that, he’d told Jenkins to stop obsessing over the Burleson grave. Even if he managed to locate the site, Kesselus insisted, any artifacts would be unsalvageable or, more likely, hidden deep in a thicket, there to remain for all time.

Kesselus declined to go along. It was Sunday, after all, and he needed to preach.

“There’s nothing out there,” Kesselus told Jenkins when he called that day.

“That doesn’t matter,” Jenkins said. “I’m going.”

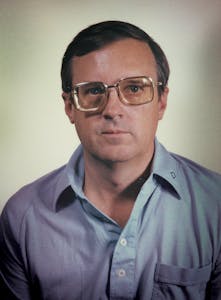

It was April 16, 1989, and Jenkins was at something of a personal crossroads. At 49, he had spent much of his professional life as an internationally renowned seller of rare books and Texas artifacts. In the sixties and seventies, when the state’s public cathedrals of culture, places like the Kimbell Art Museum and the Menil Collection, were still in their infancy, pieces of Texas history were regarded as forms of high art. Jenkins, as much as anyone, had helped create a luxury market for “Texana.”

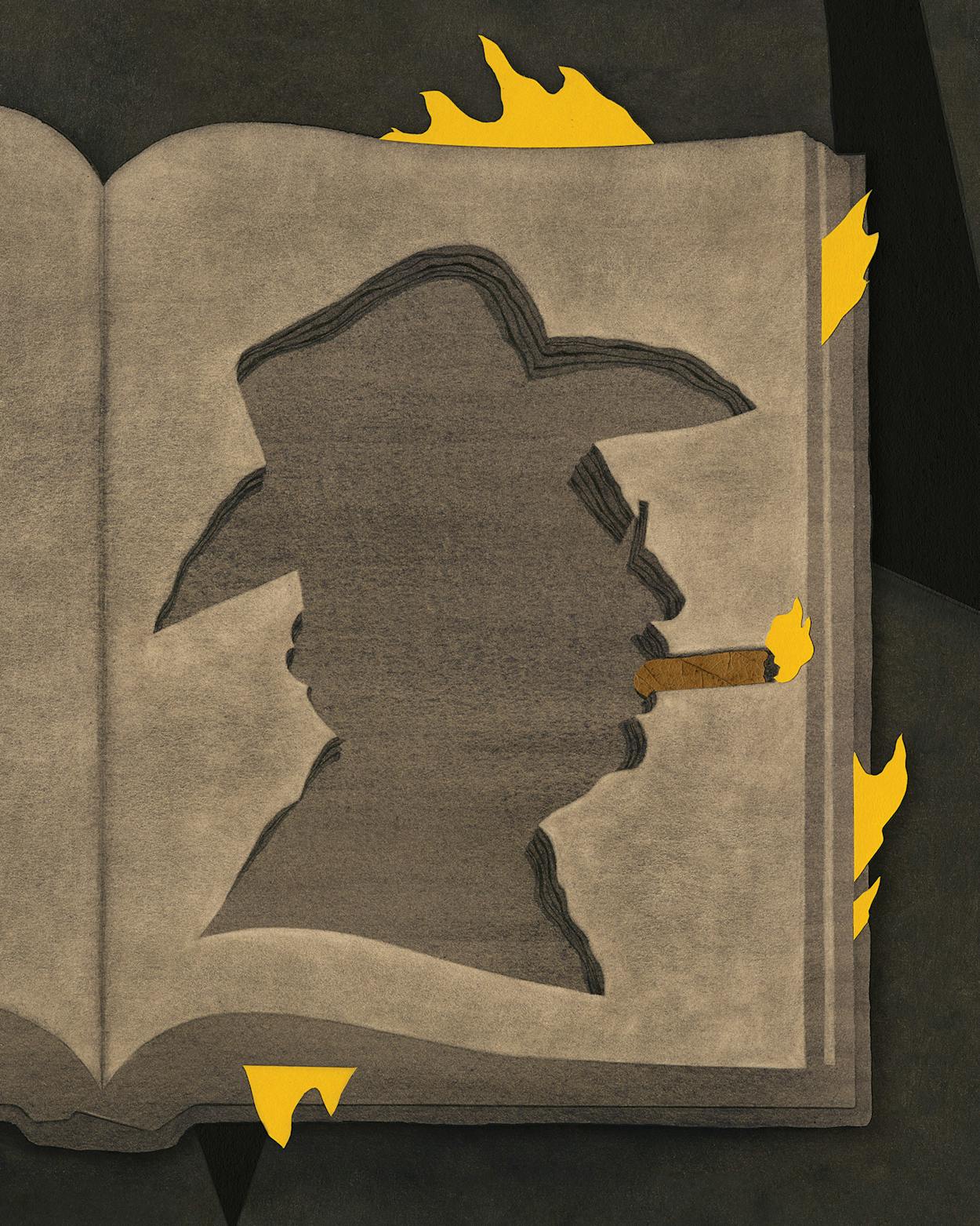

In 1975, Texas Monthly—itself in its infancy—ran an article about Jenkins for the first time, titled “So Rare: Rare books are better investments than most stock certificates.” The picture accompanying the story showed a young employee of the Jenkins Company next to a stuffed baboon, a Conestoga wagon, and some of the 350,000 books that Jenkins kept in his headquarters, a large yellow building known as the Plant, in far South Austin. Jenkins’s business had made millions of dollars along the way, and he often donned the same accoutrements—gold Rolex, towering Stetson, ostrich-skin boots—sported by his wealthiest clients.

By the late eighties, all of that had fallen apart. Depending on who is telling the story, Jenkins was broke and losing his businesses to the banks; was facing indictment for arson; was in serious debt to Las Vegas casinos; was on the run from mobsters he’d once sent to jail; was a pariah in the world of rare books; or was plagued by some combination of all of the above.

But working on the book provided an escape. Long before Jenkins was a flashy dealer of Texana, he’d dreamed of being an author and a scholar—he published his first book in May 1958, not long after graduating from Beaumont High School as valedictorian—and completing the Burleson book could provide a desperately needed win at a time when his life was a mess. And so, on that April morning, Jenkins dressed and grabbed the keys to his wife’s gold Mercedes. He drove forty miles east from their home in Austin, crossing a wide-open prairie until he arrived in a tiny town called Utley. He turned down a rough farm-to-market road and eventually reached a clearing beneath an underpass, a popular spot for day-trippers known as Humpback Bridge, where a small decline carved in the dirt led to the river. He parked the Mercedes. Then he set off for the waters where he’d been so many times before.

In the spring of 2017, I traveled to Galveston to tour the Bryan Museum with its founder, J. P. Bryan. The museum’s billing as “the world’s largest collection of artifacts relating to Texas and the American West” seemed hyperbolic, but the collection did not disappoint. The history of the state unfurls in the halls of the building’s opulent interior, appointed with dark woods and marble and brass trims. Bryan had spent most of his career in the oil and gas business, but in his later years he made his mark as a preservationist and is now focused on his earliest hobby: collecting Texana. He stocked the museum, which opened in 2015, with items from his personal collection. Near the end of the tour, I asked him if there was one specific artifact that had eluded him in his five decades of collecting, and he pointed to a poster of the Texas Declaration of Independence, a version similar to something you might see hanging on the walls of a seventh-grade classroom. “I wish I had a real one, but I don’t,” Bryan said, adding that he had once spent $25,000 on a Declaration that he thought was authentic. “I didn’t find out until maybe five years after I bought it, but it was fake.”

“Who could fabricate, much less sell, a faked Texas Declaration of Independence?” I asked him.

“My old business partner,” Bryan said. “His name was John Jenkins.”

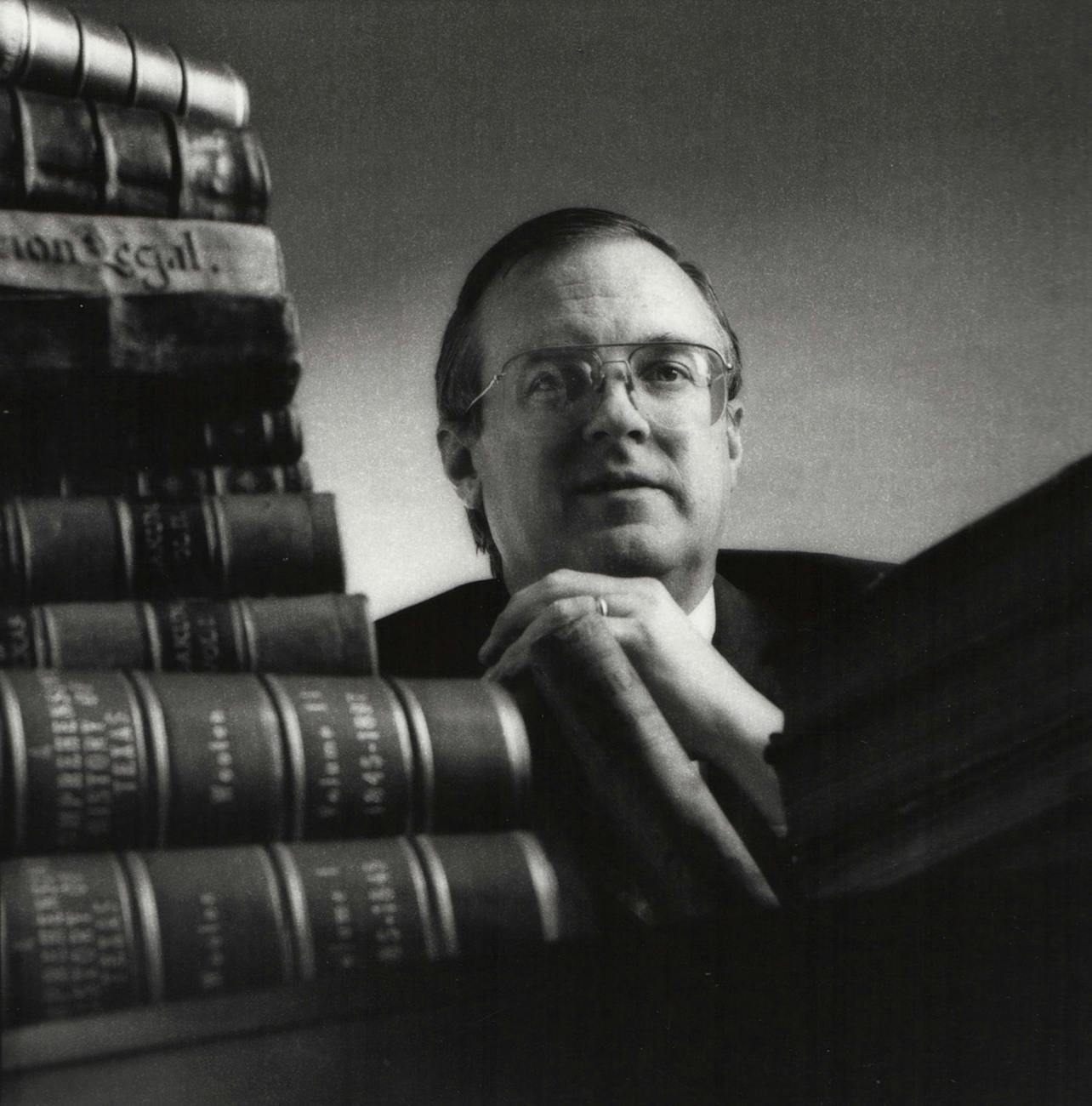

Bryan had met Jenkins in the sixties at the University of Texas at Austin. Both were studying law, and both were already somewhat established collectors. Bryan had purchased his first piece of Texana, an old Sharps pistol, when he was a boy. Jenkins was splitting time between law classes and a rare coin business that he ran with his wife, Maureen, out of a storefront in downtown Austin, just blocks from the Capitol. Bryan soon joined them as a partner; he invested in the coin business and helped start a rare books trade in the shop.

At first they made money, and they expanded by opening their own press to publish out-of-print titles they felt were noteworthy, such as the first cookbook written in Texas and an early biography of J. Frank Dobie. Jenkins used the imprint for his own writing, too, often focusing on obscure Texas characters whose stories had gone untold. He published, for example, a short biography of Monroe Edwards, a once-infamous slave trader who’d made a fortune by forging documents, before disappearing from the state.

Eventually their partnership came to an end. Bryan split with Jenkins shortly before graduating from law school. “By the end, we had become a little bit, I don’t want to say adversarial, but competitive with one another,” Bryan said. “He would always find some way to surprise me, to get something for his own that I rightly thought we should have shared. There was some tension, but I thought, ‘That’s the price of admission with John Jenkins.’”

I left the museum wanting to know more about Jenkins, and it didn’t take long to learn the story of his death. A fisherman had found Jenkins’s body partly submerged in the Colorado, across from the boat ramp where he had parked the gold Mercedes. He had been shot in the back of the head. His wallet was found in the dirt nearby, nearly empty; the Mercedes was still there, but the keys were gone. Investigators didn’t find a gun at the scene or much evidence at all that could indicate what happened. The Bastrop County sheriff called the death a suicide. The justice of the peace ruled homicide.

In October 1989, six months after Jenkins’s death, the New Yorker published an article by Calvin Trillin about Jenkins’s life as a Texana dealer. “His death was front-page news,” Trillin wrote, “not only because of the violent circumstances but also because he had often been on the front page when he was alive.” But the article didn’t offer a definitive account of what happened on that day. “Both in Austin and Bastrop County,” Trillin wrote, “there’s a feeling that there may never be much more known about what happened to John Jenkins at the boat ramp that Sunday.” Trillin ended the article with a quote from one of Jenkins’s childhood friends, who believed that whatever happened, Jenkins had almost certainly orchestrated some surprise to come, some message to deliver from the afterlife. “I like to think he developed a great story with a kicker,” the quote read. “He wrote a novel, or a movie script, and he sent it to someone in Kathmandu. And he said, ‘In a year, send this to my wife, and the proceeds are to go to my estate, and I’m to get proper credit.’ If it doesn’t have that part, it’s not Jenkins.”

Thirty years later, no one can agree on what really happened to Jenkins. People who know his story—or those who knew him personally—hypothesize and argue about what clues he may have left behind. What was the kicker? What was the part that made it “Jenkins”? I found people on both ends of the spectrum, from family members who insisted that Jenkins was murdered to old associates and friends who swear he died by suicide. Regardless of what people believed, though, they all had a story to tell.

Here’s where the story begins: After his split with Bryan, Jenkins left school and started making bigger plans. He sold his remaining coins and purchased a large yellow building in far South Austin, to house his growing inventory of Texana, which by 1970 had become his focus. He spent much of that year traveling to auctions and scored a huge portion of the remaining inventory of the Washington, D.C., bookseller Lowdermilk’s, the same store that Larry McMurtry used to start his own shop, Booked Up, which he would famously move from D.C. to his hometown of Archer City some years later.

At the time, there was a renewed interest in collecting Texana. Children of the fifties, having grown up watching shows like Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett, now had money to spend, thanks largely to the post–World War II boom. At the same time, wealthy oilmen were leaving the oil patch and moving into high-rises in Houston and Dallas, and, in a few cases, the chambers at the state Capitol. Nothing completed an office setting better than a musket from the Alamo or a bookshelf full of first editions by Dobie or Webb. “It was a wild time,” the late screenwriter and Texana buff Bill Wittliff told me, not long before he died, last summer. “Johnny was one of the players, and he knew a world about rare books.”

Jenkins was set on being more than a player in the industry. He wanted to be the industry. In those early years of his business—he called his company, simply, the Jenkins Company—he spent most nights at his big yellow warehouse or his office at home, working to catalog his stock, or scheming a way to pay off the banknotes that were financing his collection. What he couldn’t sell to customers he wanted to trade with his friends, and plenty of those deals were hatched at the card table during the marathon poker sessions that Jenkins hosted, where he’d sit cross-legged in his chair puffing away on a Cuban.

In another Texas Monthly article about Jenkins and those “devil-may-care days of selling and collecting Texana,” the magazine’s then editor in chief, Gregory Curtis, wrote, “In one trade that took two days of constant negotiation, Jenkins got a Rolls-Royce, a Kentucky rifle, and a Bowie knife; Price Daniel Jr., the son of the former governor and a book dealer before he became a politician, got a book collection; the car dealer who had owned the Rolls got an antique racing car; a restaurant owner got several thousand Cuban cigars; and [Texana dealer Dorman David] got a $20,000 credit at [legendary restaurant] Maxim’s in Houston, which he traded for some rare wines, which he in turn traded to Jenkins for books and documents. What fun!”

Trillin, in his New Yorker article, put it this way: “In Texas, which has an honored pioneer tradition of haggling and bartering, trading among people who dealt in books and antiques evolved during the sixties into a phenomenon that nearly qualified as a spectator sport. At the center of this game was Dorman David.” David, one of the most notorious dealers in the state, was the type of obscure, soon-to-be-infamous character who excited Jenkins. He had family oil money to spend and a well-known shop in Houston called the Bookman. His drug habits and stints in jail and string of marriages and divorces were well documented but rarely overshadowed the priceless items that passed through his shop. “One time I took a mummy to Waco,” he told Trillin. “It was in a coffin—a sarcophagus of carved wood. That was a big trade.” After Jenkins split from Bryan, David became his running buddy.

McMurtry, whose book collecting, selling, and trading predated his book writing, frequented David’s store. (After David eventually went broke, McMurtry took over the Bookman for a short time, and David’s mother, Grace, became McMurtry’s inspiration for Aurora Greenway in Terms of Endearment.) McMurtry viewed Jenkins as the better collector and trader—some of Jenkins’s best pieces came from David’s stock—but what David lacked in skill or knowledge, he compensated with his flash. Learning those traits from David, McMurtry believed, was the real turning point in Jenkins’s career. “Both [men] were mavericks, consciously and proudly so—a two-man herd, conducting a kind of top-speed stampede through the trade, kicking up as much dust as possible as they ran,” McMurtry wrote in 1991. “Each strove with all his might to become a legend in his own time, and both succeeded. They didn’t work like crazy to become legends in their own time hoping not to be talked about.”

One day during the summer of 1971, a man calling himself Carl Hoffman visited the Jenkins warehouse in Austin to make a deal. Hoffman, who’d flown in from New York, was looking to move an early manuscript of the Quran and a set of engraving plates that featured intricate sketches by the famed naturalist John Audubon. The two chatted briefly about prices and provenance, and then Hoffman told Jenkins he’d call him in about a week.

What followed, in Jenkins’s telling at least, sounds like a script for a television detective series. (Jenkins, in fact, would later try to get his version adapted for an episode of Kojak.) Jenkins claimed he saw a notice in a bookseller’s trade publication alerting subscribers that a Quran and some Audubon plates had been stolen from Union College, a small liberal arts school in upstate New York. Jenkins called the FBI and, after some convincing, arranged a sting operation to catch the thieves. He flew to New York and met with Hoffman and his associates at a seedy motel in Queens, where he saw the merchandise and spent several hours negotiating a deal. At one point, Jenkins realized that Hoffman had a gun. (“A big one,” Jenkins wrote. “More like the one John Wayne wears on his hip.”) Jenkins was spooked, but he talked his way out of the situation by agreeing to meet the high price that Hoffman was demanding. But he needed more time to get together that amount of cash. He left and alerted the waiting FBI agents. Jenkins then returned, without the money, and just as he saw Hoffman reaching for his gun, the agents busted in, pistols drawn, and arrested the bad guys. According to Jenkins, the agents told him that Hoffman was a New York mobster; Jenkins was lucky to be alive.

The details of the story are hard to confirm, but the publicity for Jenkins that followed was most certainly real. Union College offered him a $2,000 reward, which he refused, insisting that the school use the money to fund a prize in his name that would be awarded to a student who compiled the best bibliography that accompanied a research project. (The “John H. Jenkins Award” was presented annually at Union until 2018.) When Jenkins returned to Austin, a group of reporters met him at the airport and wrote glowing articles about the “Audubon caper.” Up until his death, most people familiar with Jenkins knew him as the man who once foiled the mob and saved some invaluable pieces of history.

Jenkins’s business increased immensely over the next few years, partly because of his newfound fame, and by 1975, the Jenkins Company was reportedly doing $1 million a year in sales. But he was feeling restless. Jenkins began courting the wealthy Eberstadt family in New Jersey. The family patriarch, Edward, whose collection was rumored to include close to 40,000 rare books and documents, had died in 1958, and for nearly fifteen years the Eberstadt collection, as it was known, existed only as a rumor to the hordes of booksellers dying to buy a piece. For a while, Jenkins was rebuffed; Edward’s heirs didn’t want to sell. But Jenkins’s persistence paid off, and in August 1975 he completed what is still considered one of the biggest deals in rare books history. There were, along with a large cache of Texana and Western history, handwritten jokes from Abraham Lincoln and an early printing of the Emancipation Proclamation. There were contemporaneous diaries from George Armstrong Custer’s Indian wars. There were letters and journals that detail almost every American military campaign of the nineteenth century. “In thirteen years of active collecting and trading,” Jenkins wrote, “I had handled perhaps two hundred such books.” Now he had 40,000. Jenkins finalized the purchase in a room at the Eberstadt estate, in New Jersey, with twenty people—bankers, accountants, lawyers, members of the Eberstadt family, and at least one Austin police officer—present. Moving the hundreds of crates that contained the collection from the Eberstadt vault into Jenkins’s trucks took nearly forty hours.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the acquisition. The collection included unpublished documents that had been signed by the big four of the Republic of Texas: Sam Houston, William Travis, David Burnet, and Stephen F. Austin. There were sketches that outlined the plans of Father Antonio Margil to create some of the earliest Spanish missions in Texas. Jenkins found land deeds and censuses from the original Texas counties. There was a copy of sheet music, from 1836, for “The Texan Grand March,” the cover of which contained a lithograph of Stephen F. Austin receiving a sword from Santa Anna. Most importantly, according to Jenkins, the Eberstadt collection contained the petition that Austin wrote to Santa Anna on October 2, 1833, which declared the need for a separate statehood for Texas and resulted in Austin’s arrest and jailing for nearly two years. In some ways, the history of Texas was rewritten by the materials that Jenkins unearthed. “You could do a paper, maybe even a book, on the major items [in the collection],” says Don Carleton, the executive director of the Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. Soon after the acquisition, the University of Texas spent $1.4 million to purchase a sizable chunk of the Eberstadt from Jenkins. A headline in the university’s alumni magazine declared “Yale Eclipsed by UT,” and the article noted that the Eberstadt purchase positioned Texas among the best historical research centers in the world.

The sale made the front page of the now-defunct Dallas Times Herald and was covered by the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, and according to Jenkins, an Associated Press wire story ran in “virtually every paper in the world.” Jenkins claimed that he was “besieged by librarians everywhere from Yale to Huntington, from Japan and Australia to England and Germany.” The Antiquarian Bookman, the leading trade publication for bookdealers, said the deal was “fortunate for the world of scholarship.” The pieces from the Eberstadt collection had extended far beyond Texas, and Jenkins wasn’t shy about predicting the far-reaching effects of his score. According to the New Yorker, Jenkins had bragged that while cultural life in America was long centered in the East—Philadelphia in the eighteenth century, Boston and New York in the nineteenth and twentieth—he had shifted the epicenter to Texas heading into the twenty-first.

In 1980 his peers elected him president of the Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America, a position that cemented his legacy. Jenkins was a star, the most high-profile man in the industry.

In September 2017, I visited Maureen Jenkins at her Austin condo. The floors in her living room were covered with boxes of newspaper clippings, manuscripts, and sepia-toned photographs. Maureen was packing a few crates to send to the DeGolyer Library, at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, where a small collection of Jenkins’s papers is housed. Most of the photos showed the high-flying days of Jenkins’s career. Others, however, told the sadder story of when Jenkins’s warehouses started catching on fire. In one picture, taken in the fall of 1987, rows of smoke-blackened books tower above a pile of fire-licked pages strewn about on the floor of a warehouse. A metal facade bearing the words “JENKINS PUBLISHING COMPANY” is pictured in another photo, except the “O” and the “M” have been nearly destroyed by the firefighters cutting through the building to create their own entrance.

The first major fire occurred at the Plant on Christmas Eve of 1985, and Jenkins claimed that nearly 500,000 books and documents were destroyed. Investigators ruled the fire an accident, and Jenkins received more than $2 million as an insurance settlement. Despite the investigators’ ruling, many of those who knew Jenkins best were skeptical that the fire was an accident.

To understand why, it’s important to know what had changed in the Texana trade by the mid-eighties. The oil bust had ravaged the state’s economy and bankrupted some of Jenkins’s best customers. Quickly selling large chunks of the Eberstadt collection had been crucial for Jenkins to stay above water—he claimed the loans that financed the deal were costing him $700 a day in interest—but the savings and loan crisis had cut off his clients’ access to easy credit.

As the Texana market cooled, Jenkins’s interest in running a Texana-dealing business seemed to cool as well. The fame that had accompanied the Eberstadt deal had spread him thin; Jenkins was spending more time traveling across the globe on a guest-lecture circuit than traveling to the back-room book auctions that he’d used to build his business in the first place. In 1980 Jenkins had hired a young Austin librarian named Kevin Mac Donnell to oversee the company’s massive literature department. Mac Donnell told me that Jenkins’s revenue had tapered off significantly during the first couple of years that he worked there.

But the bigger drain on Jenkins’s finances was happening in Las Vegas, where, Mac Donnell says, Jenkins was spending what seemed like half the year. The stakes of Jenkins’s poker games in Austin were always high, but he never got the kind of action he found inside poker rooms in Vegas. Legendary gambler Amarillo Slim even gave him a nickname: “Austin Squatty.” In Bluffing Texas Style: The Arsons, Forgeries, and High Stakes Poker Capers of Rare Book Dealer Johnny Jenkins, which will be published this month by the University of Oklahoma Press, Santa Fe rare books dealer and onetime Jenkins acquaintance Michael Vinson writes that Jenkins had started using cash from book deals—profitable or not—to finance week-long trips to Vegas. When his own cash ran out, he opened lines of credit with casinos all over town. By the mid-eighties, he reportedly owed money to twenty different poker rooms, and according to a source who spoke with Vinson, his Vegas debt had topped $1 million.

Back at the Plant, Mac Donnell started to become alarmed over a huge deal between Jenkins and a wealthy Midland oilman and rancher named L. R. French. French was something of a godsend. He was an obsessive collector with deep pockets who wasn’t slowing down at the first signs of a bust. For a couple of years, French’s big purchases nearly offset the losses Jenkins was suffering elsewhere. French stored much of his collection in a vault at the Plant; Jenkins had promised that each time he obtained a different copy of a book or document in better condition than the one French had purchased, he’d swap it out to make French’s collection more valuable. But, Mac Donnell says he eventually learned Jenkins went the other way, replacing French’s books with battered copies and, in some instances, outright forgeries or cheap facsimiles. “A lot of people want to romanticize Jenkins, like he’s a scamp, like there’s something cute or funny about it,” says Mac Donnell, who left the company around this time to start his own rare books business. “But when people steal or forge Texas documents, they are messing with history. They are corrupting the historical record. There’s nothing funny about that.”

French realized something was off, and in 1987, he asked Mac Donnell and another Austin-area dealer, Tom Taylor, to review some suspicious pieces in his collection; they did and broke the news that he’d been duped. “I’m sitting there thinking, ‘This is the kind of stuff where people kill each other,’” Mac Donnell remembers.

Taylor, it turned out, had launched his own investigation into the alarming number of forged documents, such as the Texas Declaration of Independence or William Travis’s “Victory or Death” letter from the Alamo, that were appearing all over the Texana market in the seventies and eighties. Taylor had inadvertently purchased and sold one himself, and, as he told Trillin for the New Yorker article, “Every time I walked into a library, another [forgery] seemed to pop up.” He spent months compiling a list of suspicious documents. He found them in some of the best-known libraries in the state and even one that had been purchased by Governor Bill Clements. He tracked down nearly sixty high-end forged documents that he was able to trace back to their origin, and as he later wrote in his 1991 book TexFake: An Account of the Theft and Forgery of Early Texas Printed Documents, he found that more than half had come from the Jenkins Company, “including at least seven copies of the Travis letter and six copies of the Declaration of Independence.”

Dorman David, Jenkins’s old running buddy who, by the mid-eighties, had gone broke and was out of the business, spoke with Taylor at length about the forgeries. He confessed to making plates that were used to produce forged documents. He did so, he claimed, in the name of art. He also claimed that Jenkins eventually acquired the remaining forgeries after part of the Bookman was liquidated. “Johnny certainly knew what he was doing,” Taylor told me. “There’s no doubt in my mind about that.”

In the summer of 1987, French sent a truckload of expensive Texana to the Plant. Mac Donnell remembers French telling Jenkins that he still had some of the forgeries and would present them as evidence if he had to alert the authorities, which he planned to do if he was not repaid in full. Jenkins had lost his whale. Two months later, his South Austin warehouse went up in flames.

Authorities, no doubt noting that this was the second fire at a Jenkins establishment in less than two years, suspected arson early on. The Travis County District Attorney’s office already had a file on Jenkins—it was compiling evidence on the suspected forgeries—and the file was sent to Joey Porter, an investigator in the office of the state fire marshal. He eventually filed a seven-page report describing the building and the damage the fire had caused. The final page details Porter’s examination of the mail room, where most of the damage occurred, and where the fire started. “The examination of the fire origin provided no evidence or indication of natural or accidental fire causes,” he wrote. “This fact, coupled with the presence of flammable liquids, resulted in a determination that this fire was of INCENDIARY origin.” In other words, someone started the blaze with the intent to damage the building.

On March 30, 1988, Dale Trimble, an attorney for the Houston firm Fulbright & Jaworski, deposed Jenkins regarding his insurance claim on the fire. (Trimble’s firm represented the underwriters.) In the testimony, Trimble states, “This fire was investigated and was found by the state’s fire marshal to have been intentionally set.”

Jenkins replies, “That is my understanding.”

“I mean, it seems like just a matter of minutes from the time you left the building until the time the fire was reported,” Trimble says.

“Yes.”

“That was the same way with the fire back in December of 1985, wasn’t it?” Trimble asks.

“Not quite the same, but similar, yes,” Jenkins responds.

“And you were the last person in the building on that day, too?”

“Yes,” Jenkins says. “I was.”

When Jenkins died, his wallet was reportedly empty except for his Social Security card, but that isn’t entirely true. There was another card in Jenkins’s wallet: the business card of Joey Porter, who had given it to Jenkins while investigating the 1987 fire. “He considered Porter enemy number one,” Mac Donnell says. “Porter was the guy dogging Jenkins. Porter interpreted [the business card in the wallet] to be a ‘f–k you, Joey Porter.’”

“That was weird,” Porter told me when I asked him why Jenkins might have left the card in his wallet. “Because I’d only talked to him one time. But we were getting close [to taking a case to a grand jury].”

J. P. Bryan, Jenkins’s old partner, was giving Jenkins legal advice around the time of the fire; he was prepared to represent Jenkins should the arson investigation be turned over to the FBI, which he feared would happen. “I can assure you that [Jenkins] knew he was about to be indicted by the fire marshal for arson,” Bryan said.

Porter, after speaking with a variety of anonymous informants, wrote another memorandum noting a likely motive for Jenkins to commit arson: he wasn’t meeting his payroll or making various loan payments, due presumably to his debts. The memo also details that a judgment of approximately $300,000 was levied against Jenkins by the FDIC, stemming from an old drilling rig investment he had made. And an Austin bank was set to foreclose on the Plant. “We came up with a figure of outstanding indebtedness from what you have given us, of $2,177,465.40,” Trimble told Jenkins during his deposition. “Give or take a dime.”

In the weeks leading up to his death, Jenkins knew he’d be at the center of the forged documents scandal if the news went public; he knew he was about to be indicted for arson; and he knew he was deeper in debt than he could ever repay.

In April 1989, a few hours after Jenkins had left home for the Colorado River, Maureen learned that her husband had been found dead. Ken Kesselus later relayed the story he’d heard from the Bastrop County coroner: A man named Robert Donnell was driving through the county on the same farm-to-market road that Jenkins took to the river, saw the gold Mercedes parked under the Humpback Bridge, and drove down to the car. The driver-side door was open. One of the rear tires was flat. A wallet was on the ground next to it. Donnell turned around and drove to the sheriff’s office, and by the time the deputies made it to the bridge, a group of fishermen had already pulled Jenkins’s body out of the water.

According to the autopsy report, the gunshot wound was a “contact type,” meaning the barrel of the gun was pressed directly against the spot where the bullet entered. The bullet had passed through the skull at an upward angle. Jenkins didn’t have any powder burns or residue on his hands. The Lower Colorado River Authority partially dammed the river to lower its level, and the county borrowed a huge magnet from nearby Bergstrom Air Force Base to drag the bottom. Investigators pulled up the keys to Maureen’s Mercedes, but no weapon was found.

Two Bastrop County agencies ruled on the death. The county’s justice of the peace, Bill Henderson, who was responsible for signing the death certificate, ruled it a homicide. But Sheriff Con Kiersey called it a suicide. On April 26, a week after Jenkins was found, the Austin American-Statesman published an article with quotes from both men. Kiersey, who’d investigated homicides for decades with the Austin Police Department before becoming Bastrop’s sheriff, said the angle was “completely compatible with suicide . . . I don’t think [Henderson] studied the facts. It’s measurable. It’s physics.” Henderson told the paper that he believed Jenkins was murdered because of those same physics. “I am not convinced,” he said, “that the path of the bullet could have been done by [Jenkins himself].”

Maureen never pursued a private investigation. “I just didn’t think about hiring an investigator,” she said, adding that she was in a fog following her husband’s death. Her sister and her sister’s two children moved in with her shortly after, and Maureen stayed busy trying to salvage what was left of the Jenkins Company. She believes that Jenkins’s habit of carrying a large wad of cash got him killed. “I feel like somebody shot him and took the money,” Maureen told me. “That was that. That’s it.”

For the most part, the case is cold. According to a spokesperson with the Bastrop County sheriff’s office, all the documents relating to the sheriff’s investigation were discarded years ago, in line with the office’s policy on record keeping. When I talked to Kiersey two years ago, he remembered the Jenkins case well. He recalled turning up “black marks” against Jenkins easily enough. He had no doubt that Jenkins had killed himself.

Henderson, Bastrop’s justice of the peace, died in 1993, but that office still has a small case file on Jenkins’s death. One of the documents is a letter from former U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough, in which he praises Henderson’s homicide ruling. Yarborough, who had settled in Austin after leaving the Senate in 1971, was a longtime friend of Jenkins’s. “He was in debt, yes, but if everyone in debt committed suicide you would have to open up some new cemeteries,” wrote Yarborough, who recalled how excited Jenkins was about his Burleson book. “I do not believe for one minute that John Jenkins would take his own life, as a noted historian, just as he was about to publish the best work of his lifetime.”

I called back J. P. Bryan to ask him what he thought happened that day at the river. “I believe it was a suicide,” he told me. “I’m not saying that because I didn’t love Johnny. But I could see what Johnny had done.”

Then he told me a story: At a poker game around 1984 or 1985—Bryan can’t remember for sure, there were so many poker games back then—the talk around the table turned to money and schemes. Jenkins stood up and declared he had concocted “the final get-rich scheme.” You get an insurance policy, a boat, and a gun, and you find a quiet body of water, he explained. You tie the gun to a balloon, stand up in the back of the boat, and shoot yourself in the back of the head. Your body falls off the boat, and the weapon floats away in the current so the cops never find it. They’ll have to say it’s a murder, and your family collects the insurance money.

“He pops up and says this. ‘I can tell you how you can commit the perfect suicide,’” Bryan said.

When Jenkins died, Bryan immediately remembered that story. In fact, he remembered Jenkins telling it more than once. “I thought it was in some ways prophetic, so to speak,” Bryan said. “The whole circumstance. The Colorado River, right by where his great-grandfather had settled, right near the location of the setting of the book he was writing. That was a statement: ‘I’ve come to where my roots are. This is where my life is going to end.’”

The palatial Galveston museum that Bryan founded is far grander than anything Jenkins ever built. (The Plant still stands in South Austin. It’s now an Adult Video Megaplex.) Outside the Bryan, fountains drip on the meticulous green lawn, which is dotted with palm trees that shade the old building. It was once an orphanage and stands as one of the few structures that survived the 1900 hurricane. When you think of all the treasures inside that tell the story of Texas, from Santa Anna’s sword to an impossibly rare copy of Cabeza de Vaca’s 1542 Relación, it’s easy to think that Jenkins would’ve loved the place.

As Bryan walked me through the museum on the first day we met, he talked about Jenkins selling him the fake Texas Declaration of Independence. He told me Jenkins had called him out of the blue offering a Declaration. Bryan was thrilled, not only to have what he thought was one of the few copies of the Declaration, but to buy it from his friend. “I loved Johnny,” Bryan told me. “I was aware there were faked documents on the market and you had to be careful. I should have known better, but it wasn’t like I was suspicious of Johnny. I thought it was the real thing.” Bryan has one regret, though. He trashed the Declaration he had bought when he found out it was fake. Authentic or not, he said, it was an authentic John Jenkins. “The story around it was so unbelievable,” Bryan says. “I’d give anything to have it back.”

This past fall, I met Ken Kesselus at his church in downtown Bastrop. He’d once served as a minister here, but he retired several years ago. He wanted to tell me about the Burleson book Jenkins was trying to finish before he died. He told me that Jenkins had started collecting documents relating to Burleson when Jenkins was a teenager, and during his time at the University of Texas, he hunted through the school’s archives to amass a gigantic file on Burleson. The documents and pictures traveled with him from office to office, from home to home. After Jenkins died, Maureen gave the file to Kesselus. He finished the book and published it himself, in 1990, through the old Jenkins Company imprint.

Today, Edward Burleson: Texas Frontier Leader is difficult to find. Copies are available through online sellers for hundreds of dollars, but the Briscoe Center, where pieces of the Eberstadt collection are housed, keeps a library-only copy on hand. According to Kesselus’s introduction, Jenkins’s obsession with Burleson would wax and wane over the years, but it crested again a few years before his death, when, for the Texas sesquicentennial, a group of historians named the 25 most important figures in Texas history. Burleson was left off the list. “It was largely the realization of this neglect,” Kesselus writes, “that initially led John Jenkins to determine that he would, by [finishing] a biography of Edward Burleson, finally revive a proper memory of him.”

Unfortunately, it’s tough to determine what a proper memory of Jenkins would look like. Would it call to mind the impassioned student of Texas history who wanted to be known as a first-rate researcher and author? The savvy collector and seller of genuine Texana? The swindler whose marks—some of them, at least—still regarded him with reluctant affection? Or the desperate man who’d been accused of torching his life’s work and perhaps put a bullet through his head to escape the financial trap he had, through years of recklessness, set for himself? (In a final indignity, Union College’s alumni magazine ran a story nine years ago that suggested that Jenkins’s heroic actions in the 1971 recovery of the stolen Quran and Audubon engravings may not have been what they appeared to be. At least one of the men involved in the scam stated that Jenkins was in on the theft from the start, though this is difficult to square with the information we have about the case.)

Inevitably, any proper memory of Jenkins will encompass all of these facets. Which is why we can glimpse Jenkins in full—that final mystery excepted—only if we give weight to all of the places where he lives on: in Kesselus’s Burleson book, in Vinson’s new biography, in the remains of the Eberstadt collection, in the minds of the handful of Texans who will tell stories about him to anyone who will listen, and in the $1,000 fellowship in his name that the Texas State Historical Association has awarded every year since 1995. Longtime members of the Texana community, Mac Donnell and Taylor included, reserve a special kind of outrage for the John H. Jenkins Research Fellowship in Texas History.

Kesselus won’t hear any of it. His dedication in the Burleson biography is one sentence long. It reads, simply, “This is John’s book.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2020 issue of Texas Monthly. Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Longreads

- Austin