This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

What did it mean that, before it opened its doors this month, the Rice School/La Escuela Rice received applications from 7,000 students for 1,275 places? That 700 teachers applied for 70 jobs? For Kaye Stripling, the principal of the Houston school, the answer was simple. “People were ready for change,” she says. In an era when Texas’ public schools are long on violence and short on motivation—when little if any learning is taking place—Stripling’s brand-new building in the southwest part of town promises to be an oasis in the education desert.

The Houston Independent School District, in conjunction with Rice University, has created a kindergarten-through-eighth-grade venture that offers a basic education with a contemporary approach: computers, uniforms, and real homework; small, bilingual classes that are economically as well as racially mixed. Kids were admitted by lottery. “It looks like an urban school, not a yuppie school,” says Stripling. The brightest students are allowed to advance according to their abilities, not their ages. Teachers work not in isolation, as has become the public-school norm, but with a team of counselors, parents, and—best of all—Rice professors, who will help develop the curriculum.

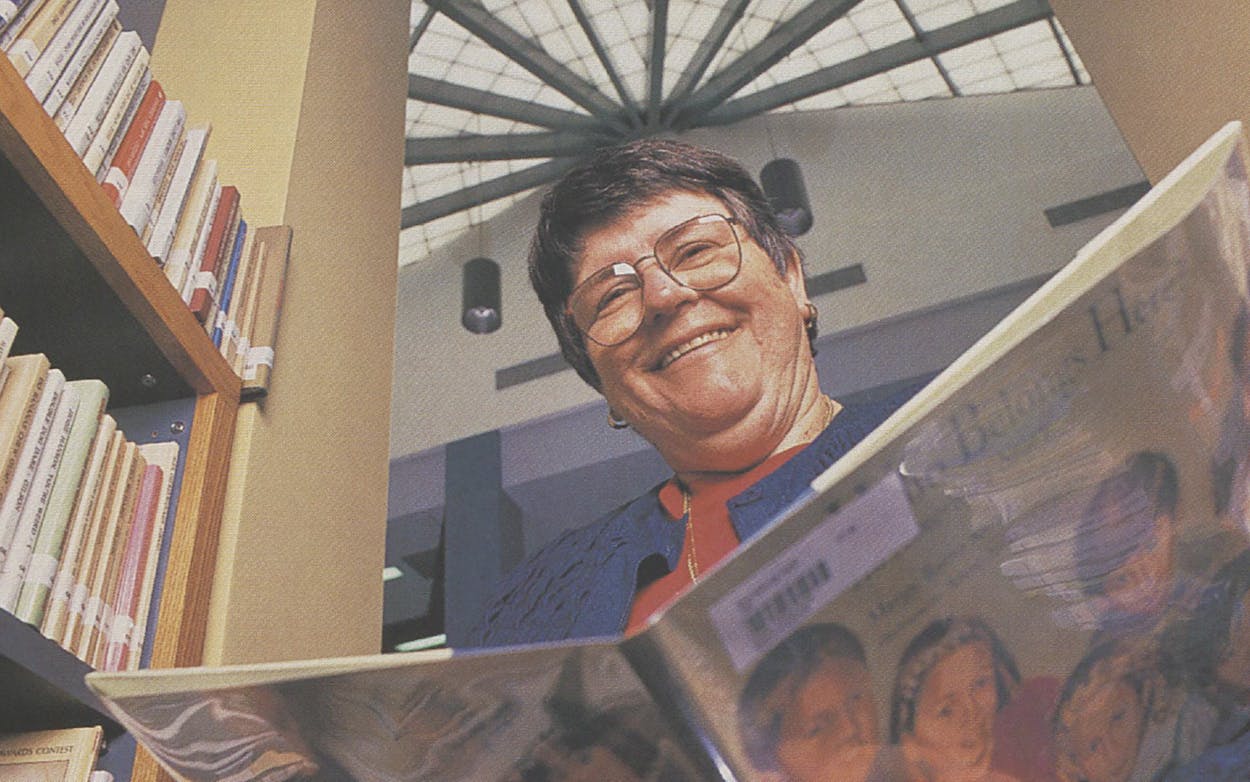

The school is the brainchild of former HISD superintendent Joan Raymond, who departed amid political turmoil in 1990. But it couldn’t have happened without the 53-year-old Stripling. A native of Willis and a veteran of the country’s fourth-largest school district, she has both the small-town skills and the bureaucratic smarts to bring the dream to life. Stripling is plainspoken—on the subject of education jargon she says, “I don’t believe in it”—and capable of forging the diciest contemporary compromises. For instance, she convinced her school’s politically correct parents and teachers that there would be no need for it to celebrate Black History Month because black culture would be celebrated daily. “She doesn’t pay homage to token things,” says a co-worker.

Stripling hopes her school will be part of one large community, not a battleground for warring factions. “We’ve generated an expectation that says this is a tough job and we’ve all got to pitch in,” she says. “Education is too complex to depend on the educators to do it.” She enlisted Houston-based Compaq to donate 1,100 computers to the school, one for each teacher and one for each child in grades six through eight. (Students in lower classes will share.) Even the education bureaucracy is welcome—within limits. Stripling has fought it in skirmishes large and small: She struggled for user-friendly chairs and tables in the dining room instead of the standard-issue “toadstools” and won another, bigger fight to spend her staff budget—equal to that of any HISD school of comparable size—as she pleased. She compromised on the textbook issue: The original plan was for a textbook-free school, but teachers now use them along with other works of their choice. “The money for buying textbooks could have gone for buying real books,” groused one teacher.

Stripling, of course, has no time for grousing. She’s too busy looking ahead. “I’ve been with the HISD for thirty years,” she says, smiling kindly while folding her arms into something resembling a body block. “I’m real tough.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Public Schools

- Houston