There’s nothing like watching the real J.R. Ewing in action. It’s an early November Friday night, and Larry Hagman is shuffling across the hardwood floor of a rented Dallas loft furnished with steer-hide throw rugs, a flat-screen TV, and a leather case full of shotgun barrels he took on a recent quail- hunting trip. Decked out in a blue terry-cloth bathrobe and a Santa Claus cap, he looks more like a carefree flower child celebrating an early Christmas than an eighty-year-old granddaddy suffering from potentially terminal cancer.

Hagman peers through a window, scanning the neon-lit obelisks of the downtown skyline, his bushy gray brows angling sharply upward, his green eyes twinkling with flecks of gold. “Once upon a time, this was all mine,” he says, flashing J.R.’s greedy, lascivious grin. Then he hastens to add, “It will be again.”

That’s not just bravura—it’s grace under extreme pressure. The way Hagman sees it, he’s enjoying two new leases on life. One is the chance to reprise the role that turned him into an international star. This month Dallas, a $54 million sequel to the pioneering prime-time soap opera, will debut on TNT, and Hagman will appear as the show’s iconic archvillain in ten new episodes.

Lease number two offers Hagman a chance to cheat death. In September, just as the new Dallas began filming, his doctors discovered a malignant tumor in his throat. On this otherwise inauspicious night, Hagman is preparing to undergo six weeks of radiation and chemotherapy treatments. A personal chef is cooking a vegan dinner the color and texture of cardboard. She enforces the ban on her boss’s once ubiquitous champagne—for years he drank an average of five bottles a day, and although he gave it up, he’s been known, even to this day, to backslide— because some nutritionists believe cancers feed on sugar.

On one end of the loft, a humidifier is steaming up a miniature cloud storm. Hagman confides that he bought it on the advice of his pal Michael Douglas. “Michael said that when you undergo radiation and chemotherapy, your saliva dries up and you can’t spit. He must know what he’s talking about. He had stage-four throat cancer. I only have stage two.”

Only stage two? That would be enough to occupy most people’s attention. Not Hagman, who seems more concerned with the fact that he’ll be filming the fourth episode of the new Dallas before he reports to the hospital on Monday afternoon. He learned long ago that the early days of a project are pivotal. Unbeknownst to most of the viewing public, J. R. was written as a supporting role in the original Dallas. It was Hagman who almost single-handedly turned J.R. into the larger-than-life character that the world came to love and hate. And he did it, through a combination of guile and charm, by the show’s fourth episode.

I ask Hagman if he’s planning to do the same this time around. He pauses to wash down a mouthful of spinach with a cup of tea. Then he flashes that J.R. grin again and says, “Of course.”

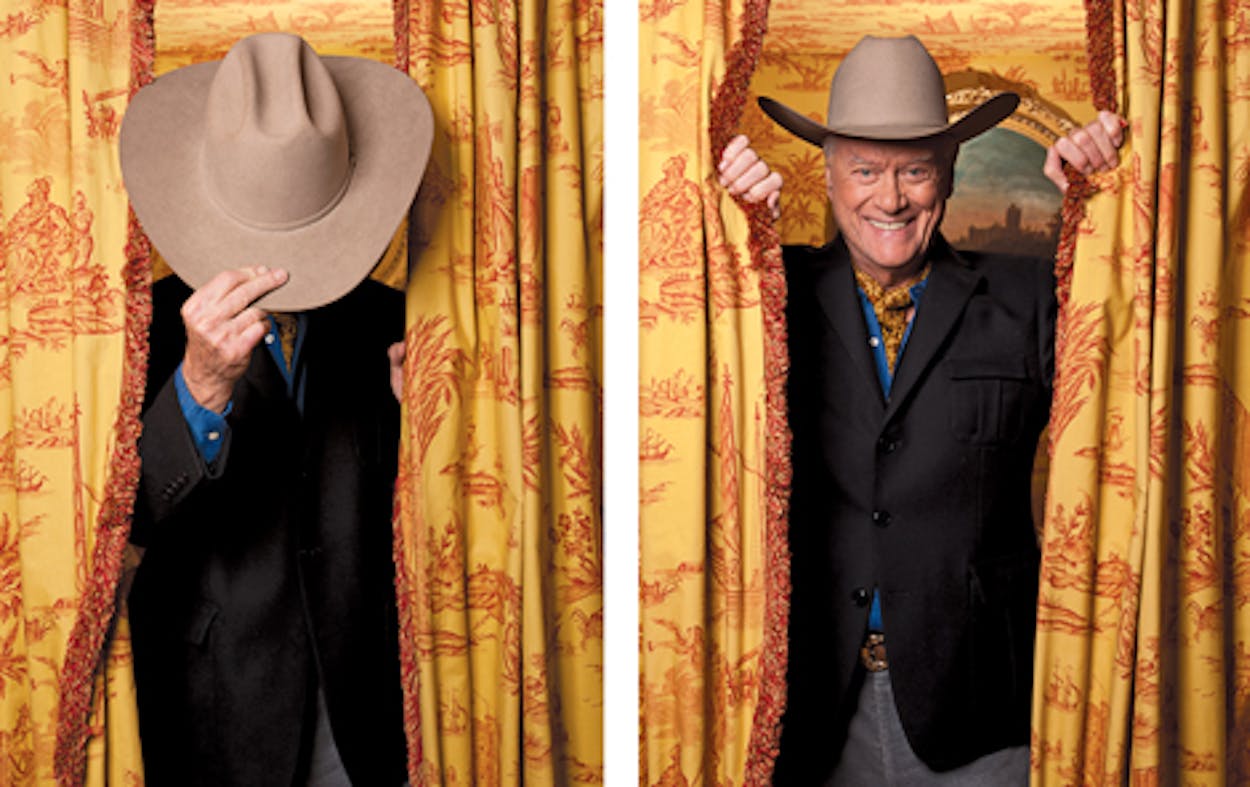

I see why he’s so sure of himself two days later when we arrive at Cowboys Stadium, in Arlington, for a quick B-roll shoot prior to the game between Dallas and the visiting Buffalo Bills. He’s toting two cowboy hats: a gray beaver skin and a straw. In a characteristically inclusive gesture, he dons the beaver skin and hands me the straw so I can more fully share in the festivities ahead. “Never leave the house without a hat,” he reminds me.

Three security men in silver blazers escort us to a luxury suite on the Ring of Honor level. With two camera crews filming, Hagman peels off from me and leads the rakishly handsome thirty-year-old actor Josh Henderson, who plays J.R.’s son John Ross, to a pair of premium seats. A shot of Hagman and Henderson appears on the 159-by-72-foot double-sided Diamond Vision screen suspended over the football field. A deafening roar erupts from the 85,000 fans in the stadium. “J.R.! J.R.!” they start chanting.

The security men whisk us down to the Cowboys sideline for the National Anthem and then up to Cowboys owner Jerry Jones’s luxury suite, where a bevy of billionaires are waiting. As we pass by the grandstands, the fans pick up the chant again. “J.R.! J.R.!”

Hagman beams, waving to the crowd even as he maintains his forced-march forward pace. I holler over the din that he seems to be having more fun than a Brahman bull at a semen-sampling rodeo. “If you don’t enjoy it, don’t do it,” he hollers back. “A lot of people can’t stand to be in crowds because they feel they don’t have any control. I love being the center of attention. Why else be an actor?”

That combination of self-confidence and shameless self-interest might as well have come out of the mouth of J. R., which makes you wonder, Is this art imitating life? Or life imitating art? In Hagman’s case, the answer to both questions is almost always yes. I know because, over the course of the thirty years we’ve been friends, Hagman has proved himself to be a shrewder and more tough-minded businessman than J.R. and perhaps twice as charismatic. At the same time, he’s got a big heart that’s made him a devoted husband, a loving if sometimes preoccupied father, and the most loyal of friends.

This month, as millions of viewers tune in to Dallas, they won’t merely be curious about how the show has been updated to reflect our era of economic anxiety and widespread resentment of the one percent. They’ll be celebrating the return of J.R., the brash, fun-loving oil baron at the core of the show. And in so doing, they’ll also celebrate the return of Larry Hagman, the brash, fun-loving actor who forged J.R. from the highs and lows of his own epic life.

Weatherford, Texas (population 25,250), commemorates one of its greatest claims to fame with a life-size bronze statue of the actress Mary Martin, born there in 1913, standing in front of the public library in her Peter Pan costume with arms akimbo as if she’s singing her signature song, “I’ve Gotta Crow.” On September 21, 1931, Martin gave birth to Larry Martin Hagman, who would become in many minds, if not hers, the town’s single greatest claim to fame.

When Larry was born, his father, Ben Jack Hagman, an aspiring lawyer, was 21. Martin was just 17. As Martin later admitted in her autobiography, she was “a mother in name only.” In 1935 she moved to Los Angeles to chase her dreams of stardom, leaving behind her soon-to-be ex-husband and her 4-year-old son. Nicknamed “Lukey,” Hagman was raised mainly by his maternal grandmother and her maid until age 6.

In 1940 Martin married Richard Halliday, a story editor at Paramount Pictures, where she was a contract player. She brought young Lukey out from Texas and enrolled him in the Black-Foxe Military Institute, alongside the sons of such stars as Bing Crosby, who had given her one of her first big breaks on his radio show. Hagman took to the school’s discipline, winning an award for excellence in a small-arms drill. But Halliday, who became Martin’s manager, subjected him to incessant verbal and emotional abuse. “Richard was a real jerk,” he recalls. “He’d berate me for anything, stuff like having loose threads on my sweater. Half the time he was shit-faced on booze. After he died, in 1973, we found out he was also hooked on amphetamines. That explained a lot.”

During his adolescence, Hagman bounced around a lot, going with his mother to New York, then getting shunted off to boarding school in Vermont, then heading back to Weatherford, where he lived with his dad and dabbled in being a cowboy. One hot Texas summer he took a job making oil-field equipment at the Antelope Tool Company in 100-degree heat. Though he hated it, he also witnessed a succession battle won by the company founder’s eldest son that left a lasting impression.

Ben Hagman wanted Larry to go to law school and take over the family practice, but a happy experience acting in a Weatherford High School play (This Girl Business) proved to Larry that he was, at heart, his mother’s son. And so, to his father’s chagrin, he left town and, after a year at Bard College in upstate New York, began his apprenticeship in earnest, putting in time with Margo Jones’s theater in Dallas; Margaret Webster’s Shakespeare workshop in Woodstock, New York; and St. John Terrell’s traveling Music Circus, where he did everything from singing in the chorus to driving tent stakes with a sledgehammer. His mother helped him make connections in the theater world, but she had mixed feelings about his decision to follow in her footsteps. For the next few decades, mother and son engaged in a rivalry that, given their closeness in age, some might have mistaken for a sibling rivalry.

By the early fifties Hagman was living in London, doing a small speaking part in a production of South Pacific that Martin was starring in and organizing entertainment for U.S. troops stationed in the U.K. One evening in 1953, he met the love of his life: Maj (pronounced “My”) Axelsson, a blond, blue-eyed 25-year-old Swedish-born clothing designer. Ten months later, they married in London. Hagman’s mother did not attend the wedding; she was in New York preparing to play Peter Pan on Broadway and in an NBC television special.

He and Maj eventually moved back to New York, where they had two children: a girl, Heidi, and then a boy, Preston. Hagman did a lot of Off-Broadway work, moved to California, and made one major film, the Henry Fonda vehicle Fail-Safe. But he got his first really big break in January 1965, when he was cast in the pilot for I Dream of Jeannie, a comedy about an astronaut who finds a genie in a bottle. After NBC ordered a full season, Hagman signed on for $1,100 per episode. He had finally hit it big, but success didn’t settle him down. Like his mother, he was driven to push himself and those around him. From the start, he kept demanding better scripts, twice threatening to quit, even when the show topped the ratings.

His impatience surely wasn’t helped by his decision during the second season to stop taking Bontril, an addictive appetite suppressant he was using to lose weight. At the same time, he also quit smoking cigarettes. The double dose of abstinence led to a nervous breakdown, complete with an on-set bout of crying and screaming. The crew carted him off in the back of a pickup truck to see a psychiatrist. Hagman’s therapy sessions would continue for three years. After repeatedly urging him to stop worrying about being in “a golden prison,” the shrink suggested, “Why don’t you drop some acid?”

A few days later, Hagman’s pal Peter Fonda took him to a Crosby, Stills and Nash concert, where David Crosby handed over several tabs of LSD made by legendary underground chemist Owsley Stanley. In his 2001 autobiography, Hello Darlin’, Hagman claims that his first acid trip took away his fear of death. The eureka moment came when he stared at his face in the mirror and saw his own molecular structure. “Some cells were dying, some were being reborn,” he recalls. “I realized we don’t disappear when we ‘die.’ We are always a part of a curtain of energy.”

Following this lysergic insight, Hagman adopted a new motto: “Don’t worry. Be happy. Feel good.” He took acid only three more times; though he never suffered a bad trip, he felt he’d had his fill. Pot became his indulgence of choice. “I liked it because it was fun, it made me feel good, and I never had a hangover,” he says.

Hagman’s feel-good philosophy didn’t mean that he was content with the political status quo. He soon became a passionate activist, though not the sort to jump on every cause du jour bandwagon, as some Hollywood celebs do; instead, he picked his crusades and stuck with them. He adamantly opposed the Vietnam War, turning down a request to tour U.S. military bases with his Jeannie co-star Barbara Eden. After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., in 1968, he participated in an acting and directing workshop in Watts and hired some of the students to work on Jeannie.

Meanwhile, Hagman took out a $100,000 mortgage on a pink bungalow in Malibu Colony, then a beachfront outpost for surfers and hippies. He wore flowing caftans to lead flag parades down the strand and dressed up in a chicken suit to ride his Harley-Davidson to the grocery store. The eccentricity that cemented Hagman’s reputation as the Mad Monk of Malibu, however, started with a physician’s recommendation. After he strained his vocal cords taping Jeannie, Hagman’s doctor suggested he not talk for a few days. Feeling healed and refreshed by the experience, he decided not to speak the following Sunday, thus beginning a tradition of “Silent Sundays.”

Hagman continued his Silent Sundays for more than twenty years, until he realized that the benefits were outweighed by missed opportunities. “In L.A., people do a lot of business on weekends, but I couldn’t talk to my agent, my producers, or anybody else,” he recalls, wistfully adding, “It was selfish to a certain degree, but I miss it terribly. It was a great discipline, and I wish I could have that kind of discipline again.”

The last original episode of Jeannie aired on May 26, 1970, marking the start of what Hagman has described as “a constant hustle for parts.” Over the next several years, he did a lot of made-for-TV movies and some theatrical releases, most of them forgettable, and even directed a sequel to the 1958 camp horror classic The Blob. It was the sort of schedule many actors would have envied, but it was tough for Hagman to shake the fear that he had hit his peak at a young age, that he would forever be known for one role—a role that barely scratched the surface of his talents.

And then everything changed. Just before Christmas 1977, Larry and Maj flew back east to see his mother perform in a benefit for the New York Public Library. As they relaxed in a friend’s apartment, they started to read two scripts from the television production company Lorimar. Larry sat in the guest bedroom and tackled The Waverly Wonders, a football comedy that eventually aired briefly with quarterback Joe Namath in the starring role. Maj settled into an adjoining room with the script for a drama about two warring Texas oil families. After reading a few pages, she came running into the guest bedroom.

“Larry, this is it!” she cried. “We’ve found it!”

The cast of Dallas gathered to read through the pilot script for the first time in January 1978, at producer Leonard Katzman’s office in L.A. Hagman, who had signed on for $11,000 per episode, arrived wearing a fringed buckskin jacket and a cowboy hat and toting a leather saddlebag. This was the first time he met Linda Gray, who was slated to play J. R. Ewing’s long-suffering wife, Sue Ellen. A lithe and vivacious brunette, Gray was a 37-year-old TV actress and model whose shapely legs had graced the famous poster for the 1967 film The Graduate. When she gave Hagman a hug, he was so tongue-tied he could manage only two words.

“Hello, darlin’,” he blurted.

“Nice to meet ya, husband,” Gray purred.

After greeting the show’s 28-year-old leads, Patrick Duffy (Bobby Ewing) and Victoria Principal (Pamela Barnes Ewing), Hagman unpacked six bottles of perfectly chilled champagne from his saddlebag, flashing what he later described as the first of J.R.’s memorable shit-eating grins.

“I just hope we all have a real good time,” he said, toasting the group.

They certainly did have a real good time, though for a while it looked to be a short-lived one. CBS envisioned Dallas as little more than a five-episode mid-season replacement and regarded J. R. as a second-tier character. But from the moment Hagman read the pilot, he set his sights higher.

Hagman based J.R. partly on the scheming Iago in Othello—that early Shakespearean training came in handy—and partly on Jess Hall Jr., the scion of the Antelope Tool Company he had observed many years ago in Weatherford. He recruited Gray as his accomplice with a method-acting move worthy of Brando. After shooting their very first scene together, Hagman offered her a ride home. While he was driving, he told her that she had performed poorly as his wife.

“I was furious,” Gray recalls. “I shouted at him, ‘I don’t care if you were Major Nelson on I Dream of Jeannie, don’t you ever, ever talk to me like that again!’ ”

At that moment, says Gray, she became Sue Ellen, and her character’s vitriolic relationship with J.R. commenced. Back on the set, Hagman and Gray started making up their own show in the background, ad-libbing lines during scenes intended to be used only as minor cutaways from the main action if needed. Katzman quickly began adding their improvisations, and soon enough, J.R. was on his way to ensuring control of the family fortune—and the show.

Dallas debuted just as the city itself was about to enter the second major oil boom of the seventies and the Dallas Cowboys were becoming “America’s Team.” The show took full advantage of this charged zeitgeist, and to everyone but Hagman’s surprise, it did well in the ratings, getting picked up for a full second season.

Dallas was as much fun to work on as it was to watch, and no one in the cast was more fun than Hagman, the ringleader. He concocted pranks on the set, kept the bathtub of his motel room filled with ice and champagne, and led raucous nighttime excursions to country and western joints like Whiskey River. The show continued to climb in the ratings through the end of its second season, ranking tenth overall. But almost no one was prepared for what happened after the third season’s finale, a cliffhanger that aired on March 21, 1980, and ended with J.R. being shot by an unseen assailant.

CBS quickly launched a promotional campaign around the question “Who shot J.R.?” and created a worldwide frenzy unlike anything in TV history. Soon the globe was awash with unauthorized, hastily produced J.R. merchandise, ranging from T-shirts and cowboy hats to dartboards, cologne, and a beer label.

Another man might have let all this attention go to his head, but Hagman instead saw a professional opportunity. In a calculated move that might have come from the J.R. playbook, Hagman took what he later called “the gamble of my life,” demanding that Lorimar pay him more money. Many of his friends thought he’d lost his mind. His mother scolded him for attempting to breach a contract. On the advice of his shrewd publicist, Richard Grant, he shrugged off all their objections and flew to England with Maj.

Hagman’s aim was to attract as much public attention as possible. That wasn’t hard. According to the BBC, one in three Britons watched Dallas. In London, Hagman partied at Annabel’s nightclub and posed for photographs alongside adoring female bobbies. Upon arriving at the Royal Ascot horse races, he inadvertently upstaged the queen of England when the crowd started yelling, “J.R.! J.R.!”

In the early fall of 1980, Lorimar finally agreed to pay Hagman $100,000 per episode, then one of the biggest salaries ever earned by a prime-time TV actor. The studio also agreed to let him direct up to four episodes per year and receive a percentage of the official J.R. merchandise profits. That was an ego boost, to be sure, but as a showbiz veteran who’d earned his spurs driving tent posts in a traveling circus, he took his triumph as a victory for his peers as well.

“When I look at the millions of dollars being paid to top TV actors today, I think, ‘Good for them,’ ” he says. “But I also think they owe me a little nod for blazing the trail in episodic television. All the former cast members of Friends ought to pay me ten percent.”

CBS’s money was well spent. “Who Done It” aired on November 21, 1980, drawing an estimated 380 million viewers worldwide. In the U.S., the audience was 83 million, more than the total number of people who had voted in the presidential election a few weeks earlier. In a preternatural Hollywood payback, the person who shot J.R. turned out to be Sue Ellen’s sister, Kristin, played by 21-year-old Mary Crosby, whose father, Bing, had given Mary Martin that early career boost so many years ago.

Dallas was now the number one show on television, and Hagman was in the driver’s seat of a brand-new Rolls-Royce. Younger women were constantly throwing themselves at him. One offered him a “Texas sandwich,” which she described as “me, you, and my sister.”

Hagman claims that he declined such come-ons. “J.R. wouldn’t have hesitated, but that was him,” he says. “I enjoyed the attention, but I knew it was best to avoid potential trouble. I made it clear to those girls that they’d missed my window of availability by thirty years. They left without stories to tell—or to sell to the tabloids.”

Unlike many of today’s self-obsessed celebrities, Hagman remained genuinely appreciative of his fans. Rather than giving them the brush-off, he coped with the avalanche of letter writers requesting his autograph by sending them “J.R. Dollars”—play money emblazoned with his likeness and printed on recycled paper. When confronted by autograph hounds in person, he engaged them by insisting that they sing him a song, recite a poem, or tell him a brief story in exchange for his “money.”

At one point, Hagman found himself in a position to give his mother a cameo role on Dallas. The idea fizzled, but even the attempt was a sign of how much things had changed between mother and son. “By then, Mother and I had learned to appreciate each other in ways that had been impossible when we were younger,” he recalls. Still, they couldn’t help continuing their professional competition. One night, when they were in Las Vegas to attend a performance by their mutual friend Joel Grey, Hagman and his mother and her traveling companion left their hotel to go to the theater. There was only one cab at the taxi stand, so Hagman offered to let her and her friend take it. Martin demurred, and the cabbie settled the debate by proclaiming, “I don’t want the lady. I want J.R.” As the taxi pulled away, Hagman rolled down the window and grinned. “That’s show business, Mom.”

But this battle of egos didn’t end there. Midway through his performance, Grey informed the audience that there were two special guests in attendance. First he introduced “my dear friend Larry Hagman, who plays J. R. Ewing on the number-one-rated show Dallas.’ ” The crowd cheered enthusiastically. Then Grey introduced Martin as “a woman who’s better known as Peter Pan.”

“People went completely nuts,” Hagman recalls. “They all stood up, with some of them climbing on their chairs for a better look, and clapped so long the house lights went up. It was literally a showstopper.” When the crowd finally quieted, Martin leaned over, tapping her son on the knee, and said, “That’s show business too, baby!”

It was during the period of Hagman’s greatest fame that I had the good fortune to be welcomed into his extended family. We met in 1981, shortly after the publication of Texas Rich, my biography of the H. L. Hunt oil dynasty. Hagman dearly desired to play Hunt in a made-for-TV movie. For various reasons, the project never came to pass, but he took me under his wing nonetheless, becoming a combination surrogate father, spiritual mentor, and pal who was always ready to lend an ear and dispense, among other things, spot-on existential advice.

When I divorced my first wife, in 1982, Hagman called to commiserate. I sputtered words to the effect that I was ready to move on. In his inimitable J. R. Ewing voice, he informed me, “It’s never over.” And he was right, of course. Eleven years later, when I wed for a second time, he arrived at the nuptial ceremony in a white suit and a gold-leafed admiral’s cap and bearing a uniquely appropriate gift: a silver-nippled Waterford crystal baby bottle filled with the prime agricultural product of Mendocino County, California. My second marriage would also end in divorce, but I still cherish that baby bottle.

In 1988 I moved to Los Angeles for a two-year stint working for Newsweek, and Hagman made sure to invite me to his house in Malibu at least every other weekend, sheltering me from the city’s hot Santa Ana winds and treating me to Hollywood moments beyond any starstruck groupie’s wildest dreams.

He introduced me to virtually all his Dallas cast mates, including Linda Gray, on whom I developed a mad crush that continues through the present day. I met his mother, who blessed me with her Peter Pan fairy dust and embraced me like I was her long-lost son, an irony that did not pass unnoticed by her actual son. I schmoozed with the likes of Peter Fonda, Lee Majors, and über-macher producer Brian Grazer. I marched in a July Fourth beach parade as both a flag carrier and a soap-bubble blower alongside Hagman’s next-door neighbor and on-again, off-again friend Burgess Meredith. (The crusty old actor once sued Hagman, claiming that the roof on his house was two inches too high.)

Thanks to Hagman, I had a pickup line unavailable to any other bachelor in L.A. All I had to do to catch and hold the attention of an attractive female was ask her if she’d like to meet J. R. Ewing, then drive her out to Malibu, where Hagman would treat her like a queen and convince her that I was Sir Lancelot in bleached-out blue jeans.

I was also privy to the genesis of a construction project that nearly rivaled the pyramids. With the advent of the twelfth season of Dallas, Maj began building the Hagmans’ seven-bedroom dream house, which at 18,000 square feet was the country’s largest solar-powered home. Dubbed Heaven, it perched atop a 2,500-foot peak in Ojai, overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

If Heaven was the high point, the low point came on November 3, 1990, when Mary Martin died of colon cancer in Palm Springs at age 76. A dark comedy quickly ensued. Hagman, who was directing an episode of Dallas on a ranch in Orange County, had arranged for his mother to be cremated. He was supposed to call the mortuary to work out the details, but he had left the contact information in his office back in Malibu. He enlisted Patrick Duffy to help him call all the Palm Springs mortuaries listed in the phone book.

When they finally located the right one, the receptionist reported that the mortician, a “Mr. Weasel,” was walking out the door with Martin’s ashes en route to the local post office to send them to Hagman. Perhaps made giddy by his exhaustion and grief, Hagman fell on the floor, convulsing in punch-drunk giggles over the man’s unlikely name. “I’m sorry you’re taking this so hard,” Weasel said when he came to the phone, misinterpreting Hagman’s laughter for hysterical crying.

The next day, Hagman presided over a memorial service for Martin in Weatherford, by now sincerely tearful. But a real-life episode that summed up their complicated relationship would always linger in the back of his mind. In 1981, after Dallas won the number one Nielsen ranking for the first time, a reporter had asked Martin what it was like to have an icon for a son. “My dear,” she had replied, “my son is a star. I am an icon.”

“That was Mother,” Hagman says, sighing.

The last and 357th installment of Dallas aired on May 3, 1991. A drunk and angry J. R. pulled out his late daddy’s Colt Peacemaker, intent on committing suicide. Then an angel played by Joel Grey showed him what the Ewing family saga would have been like if he had never existed. J.R. fingered the trigger of the Colt, a gunshot sounded, and the credits rolled on yet another cliffhanger.

Life and art after Dallas proved to be an extremely mixed bag. In 1992 Hagman joined Linda Gray in performing the Pulitzer Prize–winning play Love Letters before adoring audiences in the U.S. and Europe. That same year, he also directed an episode of the TV series In the Heat of the Night (the show’s star, Carroll O’Connor, was an old friend from his early theatrical days). But in June he was diagnosed with cirrhosis. “If you keep drinking, I don’t think you’ll be around in six months,” his doctor warned.

Swearing off booze—at least for a while—Hagman joined Peter Fonda and William Davidson, grandson of the Harley-Davidson company founder, on an Easy Rider–style road trip to the world’s largest motorcycle rally, in Sturgis, South Dakota. But in the spring of 1995, shortly after he played a Texas millionaire in the Oliver Stone film Nixon, a biopsy showed a malignant tumor in his liver. Hagman put his name on a list of five thousand other would-be liver transplant recipients.

Less than five weeks later, his oncologist, Dr. Leonard Makowka, found a donor and had Hagman helicoptered from Ojai to L.A. on half an hour’s notice. Makowka began the operation at about eleven that night, playing the Dallas theme music in the OR. The procedure took sixteen hours. Makowka later noted that Hagman’s liver was much worse than expected and that he might not have lived more than a few weeks. Hagman spent four days in the ICU, having hallucinations much like those he’d had on his first acid trip.

Despite his various doctors’ warnings, Hagman had repeatedly fallen off the wagon, and around the time of his hospitalization, he finally confronted his alcoholism with the help of a former Crosby, Stills and Nash drummer who had the providential name Dallas Taylor. A friend and former patient of Makowka’s, Taylor initiated Hagman into a Hollywood support group that included the comedian Richard Lewis. But in sharp contrast to many other reformed alcoholics, Hagman didn’t wallow in guilt over perceived past sins or affect a holier-than-thou attitude toward friends who continued to imbibe. Instead, he saw his drinking as an occupational hazard of being a performer who, depending on the shooting schedule, had to be “on” at all hours of the day and night and then had to unsparingly review countless rough cuts of himself acting. Drinking took the edge off all of that.

“I felt good when I was drinking five bottles of champagne a day,” he says. “I’d get a buzz about nine o’clock in the morning, and I’d keep it all day. But I also feel good now that I’ve stopped drinking.”

Hagman was brought up short four years ago, when Maj was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. She had always been the one who managed their investments, the cool-headed adviser who helped steer him through the shoals of show business. Suddenly, she was totally dependent. At first, he insisted on caring for her himself. But over the next two years, her condition deteriorated so severely he had to put her in an apartment with a 24-hour nursing staff. “The pain is excruciating,” he admitted to a friend. “We’ve been soul mates for over half a century.”

Hagman downsized his lifestyle, putting Heaven on the market for $11 million (recently reduced to $7 million), and relocated to a Santa Monica condo within minutes of Maj. He hired an L.A. firm to auction off his J.R. memorabilia and personal items, such as a “table-top dinner gong,” custom-monogrammed ostrich-skin cowboy boots, and a selection of his mother’s dresses.

What Hagman really wanted to do is what every actor wants to do: act. It wasn’t just about money or fame or vanity, though they all played a part. Performing was simply embedded in his DNA: he lived to act and he acted to live. In the spring of 2011, he was sent a script for the Dallas sequel. When the show’s writer-producer Cynthia Cidre called to ask if he would be interested in reprising the role of J.R. even though it was (déjà vu!) slated to be a relatively minor part, he didn’t have to think twice. “When do I report for work?” he replied.

On a cold and rainy mid-January morning, I show up at Hagman’s loft in South Dallas for an interlude of playtime. His son, Preston, is going to drive us up to Lake Dallas to check on the status of Hagman’s latest pet project: the $100,000 purchase, renovation, and retro-fitting of a 1984 Airstream RV.

Hagman looks remarkable for an eighty-year-old who’s just completed six weeks of chemotherapy and radiation treatments. He’s attired like a to-the-manner-born British bird shootist in a snap-brim cap, a green hunting jacket, and an Hermès ascot. Although his weight has dropped from 205 pounds to 185 and his voice is a bit scratchy, he’s already recovering his J. R. Ewing swagger.

“I love driving in this weather,” he says when we pile into a rented Toyota Camry. “It’s warm inside the car. We can play music on the radio. And if it weren’t for my throat cancer and my liver transplant, we could have something to drink.”

Preston smiles and nods, squeezing his six-foot-six, 325-pound frame behind the steering wheel. At age fifty, with his graying goatee, rounded cheeks, and thinning hairline, the son is in many ways the opposite of the father. He’s an aerospace engineer, not an actor; he’s been divorced three times instead of married to the same woman for more than five decades; he’s forsaken California to live in North Carolina. And yet, after a ten-year period of estrangement prompted by the usual sorts of family conflicts, Preston has renewed a bond that was sorely lacking in Hagman’s relationship with his own mother.

“I love driving in this weather too, Dad,” Preston says.

I know those seemingly simple words express some complicated emotions. “Dad and I have had our trials and tribulations,” Preston later tells me. “But I’m glad we got a chance for a do-over. I just adore him.”

Hagman is enjoying a similar rapprochement with his daughter, Heidi. When she and Preston were growing up, Hagman was obsessed with advancing his career, striving for first looks at new scripts and lobbying for acting roles. “I guess I probably neglected the kids during that period,” he admits. “Often men have to do that when they’re trying to be successful. It’s a part of life.”

After the first of his Silent Sundays during his stint on Jeannie, Heidi, then age twelve, left him a handwritten note declaring, “Daddy, as you know, I love you very much. But yesterday you were a big shit.” Like Preston, she’s since forgiven, if not forgotten. Having spent fifteen years in Seattle raising a family, she recently moved down to Santa Monica to help care for her mother. “Heidi and I are very close now,” Hagman says. “It’s wonderful.”

In Maj’s absence, Hagman’s TV wife, Linda Gray, still vibrantly beautiful at 71, is playing the part of surrogate spouse and disciplinarian. An amateur nutritionist, Gray interviewed and hired Hagman’s vegan chef. At holiday-season parties, she forbade him to eat high-cholesterol shrimp and sugary treats. When she and Patrick Duffy dropped by his Dallas loft on New Year’s Day, she limited him to a single sip of champagne. “I turned from Sue Ellen to Nurse Ratched,” Gray says, comparing herself to the female antagonist in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. “He still bitches at me because he’s got that bad-boy side that’s looking to be disciplined. But I need to get him cancer-free so he can keep acting.”

Hagman notes in his own defense that he’s been hewing to discipline most of his life, starting with military school and continuing through his days as a struggling actor. Now he takes clusters of up to five vitamin pills five times per day, and he says he’s actually beginning to enjoy the kale, cucumber, broccoli, green bean, and protein powder smoothies that are a staple of his vegan diet. His major complaint is that his ability to swallow is still limited and he has to consume most of his meals through a feeding tube attached to his stomach. “He’s been a good patient, and he’s done remarkably well,” attests his oncologist, Dr. Steve Perkins, adding, “How many eighty-year-olds do you know who look as good as Larry Hagman does?”

In fact, Hagman is performing like a man half his age both on and off the set. Prior to embarking for Lake Dallas this particular morning, he answered a six-thirty wake-up call; arrived at the TNT soundstage in South Dallas for hair, makeup, and wardrobe at seven-thirty; and made it to the Omni Hotel by eight, where he spent 90 minutes shooting a scene. Then he returned to the soundstage, where he did 45 minutes of media interviews.

Shortly before eleven, we arrive at the storage facility where Hagman’s Airstream is being readied. He pops out of the front passenger seat of the rental car like he’s been shot from a gun. He greets the men in charge of the renovating and retrofitting operations by bumping fists rather than shaking hands, a practice he’s adopted to protect his vulnerable immune system.

Like its owner, the Airstream is a unique piece of work. Silver-metal-paneled, with a bright yellow stripe and triangular yellow SolarWorld logos plastered all about, it’s 34 feet long, 8 feet wide, and nearly 13 feet high. There’s a gasoline-powered 454-cubic-inch Chevy V8 engine up front, but the electrical systems are powered by six 3-by-5-foot solar panels on the roof.

“I’ve been designing this in my mind for over a year,” Hagman says, ogling the Airstream. “You’re not going to see another one like it anywhere.”

“It’s you, Dad,” Preston adds.

“Let’s everybody take off their shoes,” Hagman commands as he leads the way into the Airstream. “I want to establish that right now.”

The RV’s interior is even more high-tech and otherworldly than the exterior. The walls of the front cabin are red, and so is the carpet. “I wanted this to look like an 1890’s Viennese whorehouse,” Hagman explains. The accessories include a gas stove, a refrigerator, and a 55-inch flat-screen TV. Along with providing ports for laptop computers and DVD players, the flat-screen is linked to four cameras focused on the front, rear, and sides of the vehicle for security purposes. It’s also linked to a dashboard-mounted iPad stand that will enable Hagman to play music, watch videos, monitor security, and make phone calls even as he drives down the highway.

The Airstream’s rear cabin is painted midnight blue with matching carpeting and curtains. Among the amenities are a shower, a full-size bed, a compartment custom-made to hold up to half a dozen shotgun barrels, and tinted windows. “In other words, you can see out, but you can’t see in,” he says, cackling with glee.

The Airstream is hardly the only sign that Hagman will maintain his reputation for eccentricity to the very end. When he dies, he plans to go out in style. His hope is to be ground up in a wood chipper like the Steve Buscemi character in Fargo, then “be spread over a field and have marijuana and wheat planted and harvest it in a couple of years and then have a big marijuana cake, enough for two hundred to three hundred people,” he told the New York Times last year. “People would eat a little of Larry.”

While he’s still breathing, though, Hagman hopes the new Dallas will earn enough viewers to be picked up for a full season, and preferably for ten full seasons. “I’d love to be acting when I’m ninety,” he says. “Why would I ever want to retire? I love what I do.” Failing that, Hagman plans to switch on a GPS and hit the open road in accordance with the motto inspired by his first LSD trip: “Don’t worry. Be happy. Feel good.”

As we leave the Airstream and head back to the loft, Preston raises the bottom-line existential question that’s been on my mind since our day began. After undergoing treatment and adhering to a vegan diet, Hagman’s throat cancer has apparently gone into remission. He does not want for food, shelter, disposable income, rewarding work, or the love of family and friends. At age eighty, he’s acknowledged as a showbiz icon, the distinction his late mother tried to reserve for herself alone. So only one question remains.

“Are you happy now, Dad?” Preston asks.

Hagman nods, grinning at us more like a little boy named Lukey who’s just found a toy he wanted under the Christmas tree than the fictional Texas oil baron who made it all possible.

“Yes,” he says, “I am.”