In 1823 Stephen F. Austin hired ten men “to act as rangers for the common defense” in protecting his colonists from Indian raids. Nearly two centuries later, that group—known as the Texas Rangers—is alive and well, having adapted from being frontier lawmen to an elite investigative force, trading their horses and bedrolls for cell phones and laptops. For the 117 men—and 1 woman—who now make up the Texas Rangers, a typical day looks more like CSI than The Lone Ranger. They have cracked many of the state’s most notorious criminal cases, having succeeded in tracking down serial killers, nabbing drug lords, coaxing confessions from rapists and murderers, and bringing corrupt public servants to account.

The transition into the modern era hasn’t always been easy, and there have been low points along the way, from the sometimes violent role the Rangers played in breaking farm labor strikes in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in the sixties to their sloppy investigation two decades later of serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, from whom they extracted hundreds of false confessions. Still, there have been far more successes than failures, and the Rangers remain one of the state’s most enduring icons. But what, we wondered, is it like to be a Texas Ranger today? Walter Prescott Webb noted in his seminal 1935 history, The Texas Rangers: A Century of Frontier Defense, that the men he interviewed were “masters of brevity when they speak of themselves—as economical of words as of pistol smoke,” and, he warned, “They do not respond to direct questions of a personal nature, and it is best not to ask them.” We ventured to ask the Rangers a few questions anyway.

“HE WAS AN OLD-TIME RANGER …”

There would be no modern Texas Rangers if not for the men who came before them.

LANE AKIN was a Ranger from 1987 to 2003. He now works in corporate security in Dallas: I knew I wanted to be a Texas Ranger when I was ten years old. I was sitting in the Yellow Jacket Grill, in Rockwall—it was 1962 or ’63—when a man came in wearing a pin-striped suit and a big white hat. He walked in such a way that you knew he was an important man. Try as you might not to stare at him, you had to. I can still remember him walking through the door with the sunlight behind him. He was with the Rockwall County sheriff, and of course I knew the sheriff because everybody in Rockwall knew the sheriff. I asked my dad, “Who’s that man with the sheriff?” And my dad said, “That’s Charlie Moore. He’s a Texas Ranger.” I was starstruck.

CAPTAIN CLETE BUCKALOO became a Ranger in 1987. He heads Company D, in San Antonio: I was a narcotics agent for the Department of Public Safety in Alpine when I met Clayton McKinney, in 1980. He was an old-time Ranger—a big, slow-moving, slow-talking, barrel-chested man. He was born and raised in Big Bend, so he knew the border, the river, the crossings, the history. He knew how people thought on both sides of the river, and they respected him and he respected them. I never heard him raise his voice. He didn’t bully people; he earned their trust. Clayton had an airplane, and he would fly us into Mexico and pinpoint airstrips that the traffickers were using. He would actually go into Mexico and steal back airplanes that had been stolen on this side of the river and were being used by traffickers to smuggle narcotics into this country. He thought that was fun.

CAPTAIN TONY LEAL became a Ranger in 1994. He heads Company A, in Houston: When I was a kid, my dad was a field officer for the Texas Department of Corrections, and our house was on the prison farm in Sugar Land. I remember him getting woken up in the middle of the night whenever there was a jailbreak or a manhunt. The Rangers would come to our house needing horses, and I can still remember how much I wanted to go out and ride and help them track down the fugitives. I would listen to my dad getting the horses and the dogs ready, and you know, it’s a very distinct sound those bloodhounds make when there is all that nervous tension in the air. Even back then, I knew I wanted to be a Ranger. I thought those guys were larger than life.

LANE AKIN: When I was in junior high, Charlie Moore came to talk to my class one day. I remember he was wearing not one but two Colt .45’s with ivory grips decorated with small, gold Longhorns. The hammer was back on both of them. I was completely captivated. I was sitting in the front row, and so the barrels of those .45’s kept passing over my toes as he was pacing back and forth telling this story about capturing some bad guys out in a rural cabin somewhere. Finally, when he got through telling all of his stories, he asked, “Are there any questions?” I meekly raised my hand and said, “The hammers are back on both your pistols. Isn’t that dangerous?” He said, “I sure hope so. That’s why I carry ’em.”

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE was a Ranger from 1982 to 2004. He is now a major at the Webb County Sheriff’s Department, in Laredo: You know, back then, most Rangers were just country boys like me. When I came into the Rangers—and you’ll think I’m kidding when I say this—I saw some of those older guys scribbling reports on napkins. They weren’t as polished as the Rangers now, but they had common sense, and they knew how to get the job done.

JOAQUIN JACKSON was a Ranger from 1966 to 1993. He is now a private investigator in Alpine: Charlie Miller started out as a Ranger around 1920. He actually was a bodyguard at one time for Pancho Villa, and he was a tough, tough old guy. After he retired, he asked a Ranger I knew named Bob Favor to come see him, and Bob later told me this story. When Bob stopped by, Charlie Miller was laid up in bed with a broken leg he had set himself. He told Bob that his horse had kicked him in the jaw and busted a couple of his teeth. He said, “Go out to my pickup and get my pliers.” Bob brought him the pliers, and Charlie Miller said, “Hand me that mirror there.” Bob handed it to him. Then Charlie Miller stood there with those pliers, and he pulled out three teeth, one by one. He had no whiskey or tequila or nothing, and he didn’t make a sound. He told Bob, “Pain’s never really bothered me much.”

LANE AKIN: By 1977 I had joined DPS, and I was a trooper over in Commerce. One day Charlie Moore came through town, and I stopped him for speeding. He was still a Ranger then. The first thing I thought when I saw him was how much smaller he was than I remembered him being when I was ten years old. But he was still big in my mind. Of course, I had no intention of writing Charlie Moore a ticket. We went to a local coffee shop, and we sat there and visited. I told him that I would love one day to be a Ranger. That’s what I’d dreamed about since I was a kid at the Yellow Jacket Grill. He told me that people would resent it if I started making noise about wanting to be a Ranger when I was still a young trooper. He said, “Keep your head down, do your job, and when it comes time, throw your name in the hat.” And that’s exactly what I did.

SERGEANT TRACY MURPHREE became a Ranger in 1998. He is stationed in Denton: You have to understand that the Rangers who came before us—even though they did a lot of heroic, amazing things—they were just men, and they were products of their times. We all have a lot of admiration for the generation that came before us. But way, way back, there were some brutal things that happened. Some of what the Rangers did back then in South Texas was wrong. You can’t hide from that. It’s as much a part of our history as the stuff we’re proud of.

SERGEANT BROOKS LONG became a Ranger in 1997. He is stationed in Ozona: The Rangers rode from El Paso to Brownsville during the 1800’s, and they controlled the border. And they didn’t do that by being diplomatic. They did it with brute force. They didn’t follow the rules and regulations to a T, but they got the job done. Nowadays there is no businessman or landowner—especially west of I-35—who would be in business if the Rangers hadn’t done what they did. There are still some hard feelings in South Texas about that history. But personally, I’ve never had a problem, because I grew up in South Texas. I speak the language, I understand the culture, and these folks are my best friends.

RAY MARTINEZ was a Ranger from 1973 to 1992. He is now retired and lives in New Braunfels: When I first got to Laredo, some people let me know that they had not forgotten the problems that had existed with the Rangers. There was one cliché that people would always say to me, and that was “Every Texas Ranger has Mexican blood”—and then they would pause and add—“on the tips of his boots.”

SERGEANT RAY RAMON became a Ranger in 1995. He is stationed in Kingsville: One time I was in Eagle Pass helping a police investigator interview some people, and I will never forget how afraid this older Hispanic man was of me. I couldn’t understand it, because I had been fair to him and treated him with respect. When we left, I turned to the investigator and I said, “Man, that guy was so scared of me. I wonder what the deal was?” He said, “You’ve got to remember, Ranger, there’s a lot of history behind you.”

“NOW, WHAT EXACTLY DO YOU ALL DO?”

Modern Texas Rangers, like FBI agents, are highly trained investigators who assist local authorities on everything from homicides to public corruption cases. But they must be versatile, especially in rural areas, where they may be called on to do just about anything.

SERGEANT MARRIE ALDRIDGE became a Ranger in 1993. She is stationed in San Antonio: People are always saying, “You’re a Ranger—wow! Now, what exactly do you all do?”

BROOKS LONG: The day I got the phone call from Austin that I was going to be made Ranger was a very proud day for me. After I called my wife and told her the news, she called our next-door neighbor, who called another neighbor on our block. And the neighbor said, “Gosh, I didn’t even know he plays baseball!”

SERGEANT CHANCE COLLINS became a Ranger in 2002. He is stationed in San Antonio: Our job is assisting local law enforcement agencies—particularly smaller, rural agencies—that don’t have a lot of resources. We assist them on cases that they might not have the manpower or expertise to handle on their own.

SERGEANT KENNY RAY became a Ranger in 2001. He is stationed in Tyler: There are a handful of small-town police departments in the two rural counties I have that, from the chief on down, have never worked a homicide. Never. They don’t have any money, any equipment, any training, any experience. When they have a violent crime, like a murder or a sexual assault of a child, they don’t even know where to start. But they can make one phone call—every one of my agencies has my home phone number and my cell—and get not only a trained investigator but all the resources of the state police: access to the crime lab, helicopters if we’re doing a manhunt, other Rangers to help investigate, highway patrolmen, everything. And the neat thing is, we don’t come in and kick them out. They are still the lead agency, and we are there to assist them.

SERGEANT KYLE DEAN became a Ranger in 1992. He is stationed in Kerrville: Some Rangers are responsible for 6 counties, some for as few as 2, and every area is different. Because we’re scattered across 254 counties, we have this networking ability. So if something happens here in Kerrville, and I need help from Lubbock, I just pick up the phone. It’s a Ranger tradition that if another Ranger calls and has something that he needs help on, you drop whatever you’re doing and you get it done.

SERGEANT DAVID HULLUM became a Ranger in 1998. He is stationed in Eastland: I probably have more training hours than all the officers in a small, rural police or sheriff’s office combined. I mean, there are no crime-scene technicians in Eastland County—I am the crime-scene tech. I take the pictures, I make the measurements, I collect the evidence, I do the interviews, I file the cases. Sometimes I kid the guys at the local agencies that I work with. I tell them, “Man, I’m just here to build the float for you to ride in the parade.” Our job is to stay in the background, so a lot of times we don’t get the press. Unlike the sheriff or the DA, we don’t have to fight for reelection.

TRACY MURPHREE: People expect a lot from the Rangers. I mean, you could find Jimmy Hoffa and it would be no big deal because you’re expected to do that. You’re a Ranger. But you could screw it up in a heartbeat, and that’s where the pressure comes in. I’ve got this fear in the back of my mind that if I don’t do this right, with one mistake I could ruin the reputation that has been bought and paid for by people long before me.

BROOKS LONG: You’ve got to be a jack-of-all-trades out here in the rural areas. In any given day, you may have to investigate anything from capital murder to livestock theft.

SERGEANT JESS MALONE became a Ranger in 1994. He is stationed in Midland: I’ve helped investigate close to three hundred homicides in my thirteen years as a Ranger. They don’t pay me for what I can do, they pay me for what I know. I can see things in a crime scene that maybe a younger, more inexperienced officer might miss. So the homicides I work are the whodunits, not the smoking guns. A case that jumps to mind is a violent homicide of a female who had been bludgeoned to death with a hammer in the Odessa area. It was a gruesome crime scene—there was a lot of blood on her tile floor and shoe prints in the blood. At first glance it looked like two perpetrators had been in there, because there were two sets of shoes: tennis shoes and hiking boots. But as I got to looking at it, I saw that the tennis shoe was consistently a left foot and the hiking boot was consistently a right foot. I said, “There were either two guys in here, both of them hopping around on one foot, or there was one guy with two different shoes on.” The police department did a wonderful job finding the guy, and he had two different shoes on when they found him. He had an ankle injury, so he was wearing a hiking boot on one foot to support his ankle. We were able to make a case on him and arrest him.

CAPTAIN GERARDO DE LOS SANTOS became a Ranger in 1989. He is stationed in Austin and heads the Unsolved Crimes Investigation Team: You can’t do this job for very long without seeing the worst of what one human being can do to another. I’ve seen every which way you can kill a person—stabbed, burned, decapitated, cut up in pieces. You name it, I’ve seen it.

RAY MARTINEZ: People see the Rangers as neutral, so Rangers are often called in when county officials are being investigated for misappropriation of funds, corruption, voter fraud, what have you. The biggest case I ever worked was in Duval County, after George Parr committed suicide on April Fools’ Day, 1975. Parr had ruled South Texas through the patrón system for decades, and he had enormous power; he could deliver votes and guarantee that a certain candidate would win the governor’s race or other state offices. When he killed himself, there was a war between the factions to see who was going to control the county. Attorney General John Hill and some of his assistants, as well as us Rangers, went down there, and we started investigating the corruption that existed. My Ranger buddy Rudy Rodriguez and I lived in a motel in Alice for two years. We would go out at night and meet with the locals and eat fajitas and drink beer with them. We would earn their confidence and get them talking. I believe we ended up with 118 indictments, and we were able to obtain convictions in about 98 percent of them.

“BUT THEY NEVER TOOK AWAY TRICKERY.”

Until the sixties, when new court rulings hemmed them in, the Texas Rangers could do as they pleased when they interrogated a suspect; they could rough him up, browbeat a confession out of him, or move him from one county to the next so his attorney couldn’t find him, a practice sometimes called the Mexican two-step. Now Rangers, whose every move is scrutinized by defense attorneys and jurors, must adhere to stringent rules if they want their suspects’ confessions to be admissible in court. And yet Rangers have proved to be more skillful than ever in getting suspects to tell them about their crimes.

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: A lot of the old-time Rangers were not happy when they had to start reading Miranda warnings to suspects. They thought the world had ended. They couldn’t figure out why on earth you would want to spend months investigating a case and hunting down a suspect, and then once you’ve got him, the first thing you have to say is “You have the right not to talk to me.”

JOAQUIN JACKSON: The courts gave us the writ of habeas corpus, so Rangers couldn’t take a suspect to New Mexico or the Panhandle or South Texas while his lawyers were looking for him. Then they gave us Miranda. But they never took away trickery.

GERARDO DE LOS SANTOS: I had a case in Montague County in the early nineties, a homicide in a drug deal gone bad. We knew who had shot the victim, and we knew that the suspect and an accomplice had dumped the body, but we didn’t know where the body was. One day I visited the accomplice at work, and he agreed to come down to the police department for questioning. He told me, “I had nothing to do with that guy’s murder!” I said, “I know, I believe you. I also know where the body’s at, but I want to know the route you took. I’d really like for you to show me. If you lie to me, I’ll know it, and I’ll tell the DA you’re not cooperating.” He agreed, and so we went out into the country. He’d say, “Turn right here,” and I’d say, “Good, good,” like I knew where we were going. This was all a giant bluff, of course. Finally he said, “Okay, stop right here.” We got out of my car, and he took me through the brush, showing me how they carried the body. Finally we got to a ravine and he said, “We dragged him all the way out …,” and he looked down and the body was lying right in front of him. He was completely shocked. He looked at me and said, “I thought you’d found him!” And I said, “I just did.”

RAY RAMON: I remember Oscar Rivera, another Ranger, gave me some good advice. He told me, “Ray, if you ever want to get confessions from people, you have to be patient and you’ve got to be their friend. And you’ll be surprised at what people will tell you.”

DAVID HULLUM: When I first started my career, I thought the way you got confessions was you just hollered and screamed and finally the guy would confess. And then I got around investigators who knew what they were doing, and I realized that you can’t be confrontational. The first thing I’ll tell a suspect is “Look, I’m not here to judge you. I’m just here to deal with the facts pertaining to the offense.” They really respond to that. I’ve got a pretty high confession rate, which just goes to show you that even a blind hog can root up an acorn every once in a while.

TRACY MURPHREE: What you really want to do when you’re sitting across from a child killer or a child molester is reach across the table and strangle him, but you’ve got to buy him a Coke and talk to him and get on his level. I had a case in Lewisville where a four-year-old boy was beaten to death and his body was found stuffed in the trunk of his father’s car. I’ve got little ones at home, so that was very hard for me to comprehend. But I interviewed the boy’s father with Lewisville police, and we kept our cool and got down on his level. We told him that we understood that kids cry and drive you nuts and that accidents happen. We knew that we would be able to prove in court that it wasn’t an accident, but he went with that version of events. We got a confession, and now he’s doing life in prison.

KENNY RAY: I had a case where a guy was raping his own little girl. Not only was he doing that, he was allowing a friend to come over and rape her too. She was six years old. What you do when you sit down to talk to someone like that is you just decide that you’re going to be an advocate for that little girl. That’s what motivates you to sit there and deal with a monster like that in a humane way. Most of us are daddies, so the first thought that comes to mind is you just want to put a boot on the guy’s neck.

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: There are a lot of expectations on a Ranger’s shoulders when he walks into a room to question a suspect. If he’s working on ten different cases, what does his community expect him to do with those ten cases? They expect him to solve all ten cases. They expect him to bat a thousand. They pay baseball players millions of dollars when they bat three hundred, but they expect us to bat a thousand so that is what you’ve got to have in your mind when you walk into a room to question a suspect: “I’m going to bat a thousand.”

AL CUELLAR was a Ranger from 1978 to 1996. He is now retired and lives in Helotes: You have to make a suspect like you; you have to make him want to tell you what he did. And another thing: You can’t go in there on an empty stomach, because you don’t want to tire out before they do. Go in there full, and them hungry.

SERGEANT MATT CAWTHON became a Ranger in 1992. He is stationed in Waco: Al Cuellar could get a confession out of someone and they would thank him. He’d say, “You’re at a crossroads in your life, and you can choose the right path or the wrong one. You can tell me what happened.” And they’d tell him everything.

AL CUELLAR: When I was promoted to Ranger in ’78, there weren’t but two Rangers besides me who could speak Spanish, so I was traveling all over the state interviewing people. I got confessions from murderers, from rapists, from arsonists and thieves. I would spend an hour chitchatting with them about everything in the world before we’d talk about what they had done. My favorite line I’d say—and it was very successful—was “And then things got out of hand, didn’t they?” A lot of times they would just nod their head. It was their first admission of guilt. They wouldn’t say anything at that point, they’d just nod their head, and I’d know that I had broken them.

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: A good old boy who has the gift of gab, who can get out there and talk to people—that’s something that’s never going to be outdated. I’ve never seen anybody set a computer in a room with a crook and then walk out with a confession.

“YOU CAN TAKE THE HORSE AND THE WINCHESTER …”

In the past fifteen years, DNA technology and fingerprint analysis have transformed the Rangers’ job, allowing them to close cases that would otherwise remain unsolved.

CAPTAIN KIRBY DENDY became a Ranger in 1987. He heads Company F, in Waco: The cases are the same as they used to be, but the manner in which they’re solved—and the speed in which they are solved—has changed. Then again, in some cases, we don’t have any DNA evidence or fingerprints to work with, and the investigation still takes the same legwork and effort that it did a hundred years ago.

JESS MALONE: No matter how good the technology gets, some cases still require a lot of windshield time—just driving up and down the road, following leads.

CHANCE COLLINS: Jurors expect a lot more from us today because they watch shows like CSI, and criminals are getting savvier too. They will alter a crime scene based on what they have seen on TV. I had a case where a guy had stabbed a man more than twenty times, and before he left the victim’s house, he turned the thermostat all the way down. He told me in his confession that he had done that because he knew that the temperature could throw off our estimation of the time of death. The only problem? He left a bloody fingerprint on the wall.

SERGEANT FRANK MALINAK became a Ranger in 1993. He is stationed in Bryan: I tell people, “You can take the horse and the Winchester, but if you give me a cell phone and a laptop, I can get my job done.”

DAVID HULLUM: After I was promoted to Ranger, I decided to reopen a 1987 capital murder case of an old spinster in the town of Rising Star who had been sexually assaulted and strangled to death. I approached eight or nine men who had been questioned in the original investigation, and they all agreed to give me DNA samples, but none of them matched. Finally I tracked down this guy Leonard Self, who the police had looked at back then, and I visited him in jail in Abilene. He was real evasive, and he refused to give me a DNA sample. He was in jail for something minor, like a suspended driver’s license, and so I made some calls to see if he was on the jail’s work crew, which he was. I asked another Ranger, Calvin Cox, to use his connections at the jail. I said, “Get one of those jailers to let him smoke a cigarette when he’s working. After he smokes it, have the jailer pick that cigarette butt up.” The rest is history. DNA testing showed that only Leonard Self could have left the semen at the scene of the crime. He’s serving a life sentence now.

SERGEANT DAVID MAXWELL became a Ranger in 1986. He is stationed in Bay City: When I was in college, my intention was to become an attorney. And then, in 1969, my sister was murdered. She was 25, and I was 20, so this had a huge impact on my life. She had been working as an operator for Southwestern Bell Telephone, and when she went to work one Sunday, this man accosted her when she got out of her car. He drug her into an abandoned building, tied her up, raped her, and stabbed her to death. There was a vigorous investigation, but it never went anywhere. By 1972 the case was still unsolved, and so I decided to go into law enforcement. I joined DPS, and I made it my goal to become a Texas Ranger. It was my hope that, somewhere down the line, I could reopen my sister’s case and bring it to a conclusion.

FRANK MALINAK: I began my career in law enforcement at a time when even if you had good, readable fingerprints at a crime scene, they didn’t necessarily help you in your investigation. Unless you had a suspicion of who had committed the crime, they didn’t tell you much; you had to know which suspect to compare the prints to. Nowadays, with AFIS—the Automated Fingerprint Identification System—we enter fingerprints into a national database. I’ve gotten cold hits in cases where we had no suspects whatsoever.

DAVID MAXWELL: I tried reopening my sister’s case in 1986. After this man killed her, he stole her car and abandoned it several blocks from the crime scene. The Houston Police Department was able to lift his prints, so we had them on file. In ’86 the AFIS system was still in its infancy. It was rudimentary compared with what we have today—it just searched fingerprints that HPD had in its files—and we didn’t find anything. I did that kind of check periodically, because, of course, the technology was still developing.

FRANK MALINAK: Before I became a Ranger, I worked for the sheriff’s office in Lee County. There was a case I investigated there that I’ll never forget. In 1982 a woman was staying at a hotel in Giddings, and she was on the phone with her business partner up in Dallas when someone started knocking at her door. She called out and no one answered, so she cracked the door open to see who it was. The first thing that came through the door was a fist. This guy hit her so hard that he knocked her false eyelashes off. He ripped most of her clothes off and tried to beat her to death. Her business partner was still on the phone while all this was going on, thank goodness, so he called the front desk. The two managers came around the back side of the hotel and beat on the door. A short time later, the light went off inside the room; the guy bolted out, past the managers, and escaped into the darkness. He was never caught. In the photographs that were taken at the hospital, the victim was unrecognizable. She had to have many, many surgeries. We worked this case for years. We had the guy’s fingerprints; he hadn’t been able to find the switch when he tried to turn the lamp off, so he had unscrewed the lightbulb. But we had no suspect. We would come up with a name, but the prints wouldn’t match, and we did that for years.

DAVID MAXWELL: Four years ago I contacted a good friend of mine, Jim Ramsey, who was a homicide detective with HPD. Jim was one of their premier homicide detectives. Now, I’d known Jim since he was eighteen years old, when he was a cadet and I was a highway patrolman, so we’d been friends for thirtysomething years. But I had never really shared the story of my sister’s murder with anybody. I just didn’t talk about it. I went to Jim, and I told him the story. I asked him to pull the file, and he and I worked the case together. So that’s how we got started. When we pulled the file, we saw that the fingerprints weren’t there. The evidence was gone, the crime-scene photographs were gone—we had nothing. We searched and searched and searched. Finally, after some pressure was applied, several detectives were assigned to go through all the old homicide cases that were still open, and they found the fingerprint cards misfiled in a 1984 homicide. Once we got the cards, we submitted them to the statewide AFIS system, in Austin. A woman named Jill Kinkade spent three days running them and got a hit.

FRANK MALINAK: Years later, I’ve left the sheriff’s office, I’ve been through my tour of duty in highway patrol, I’ve spent seven years as an investigator in DPS auto theft, and I’m a Ranger in Midland. And I’m in a murder trial that takes me back to the area where this crime happened, and I got to thinking about the woman who was attacked in Giddings. AFIS was up and running by then, and so I got the prints submitted. Three days later we had a hit. This was more than twelve years after the crime. We charged the suspect with attempted capital murder. He was living in La Grange, eighteen miles away. He had a criminal record as long as your arm. We arrested him, went to trial the following year, and the jury sentenced him to 99 years in prison. When I called the victim to tell her that we had found the man who did this to her, she said, “There’s not a day that’s gone by that I haven’t thought about that horrible, horrible night.”

DAVID MAXWELL: Jim Ramsey and some Rangers were able to locate the suspect in Texarkana. I was ecstatic. But I also knew that Jim would have to get a confession because there was no physical evidence left. Any chance to do DNA tests had been lost. Jim drove to Texarkana, and he interviewed the suspect, James Ray Davis. It was a cold interview; the guy had no idea Jim was coming, and he had no idea what Jim was there to talk to him about. Jim taped the interview, and the guy ended up giving him a confession. He and his attorney decided to plead guilty, and on January 15, 2004, Judge Brian Rains sentenced him to life in prison. Before this had come to a conclusion, my dad, who is elderly, had told me every time I saw him, “Son, if you can find out who killed your sister before I die, that’s all I want. I just want to know who killed Diane.” So it was a good feeling that both my parents lived to see that day.

“THE RANGER BADGE IS STILL MADE FROM A CINCO PESO.”

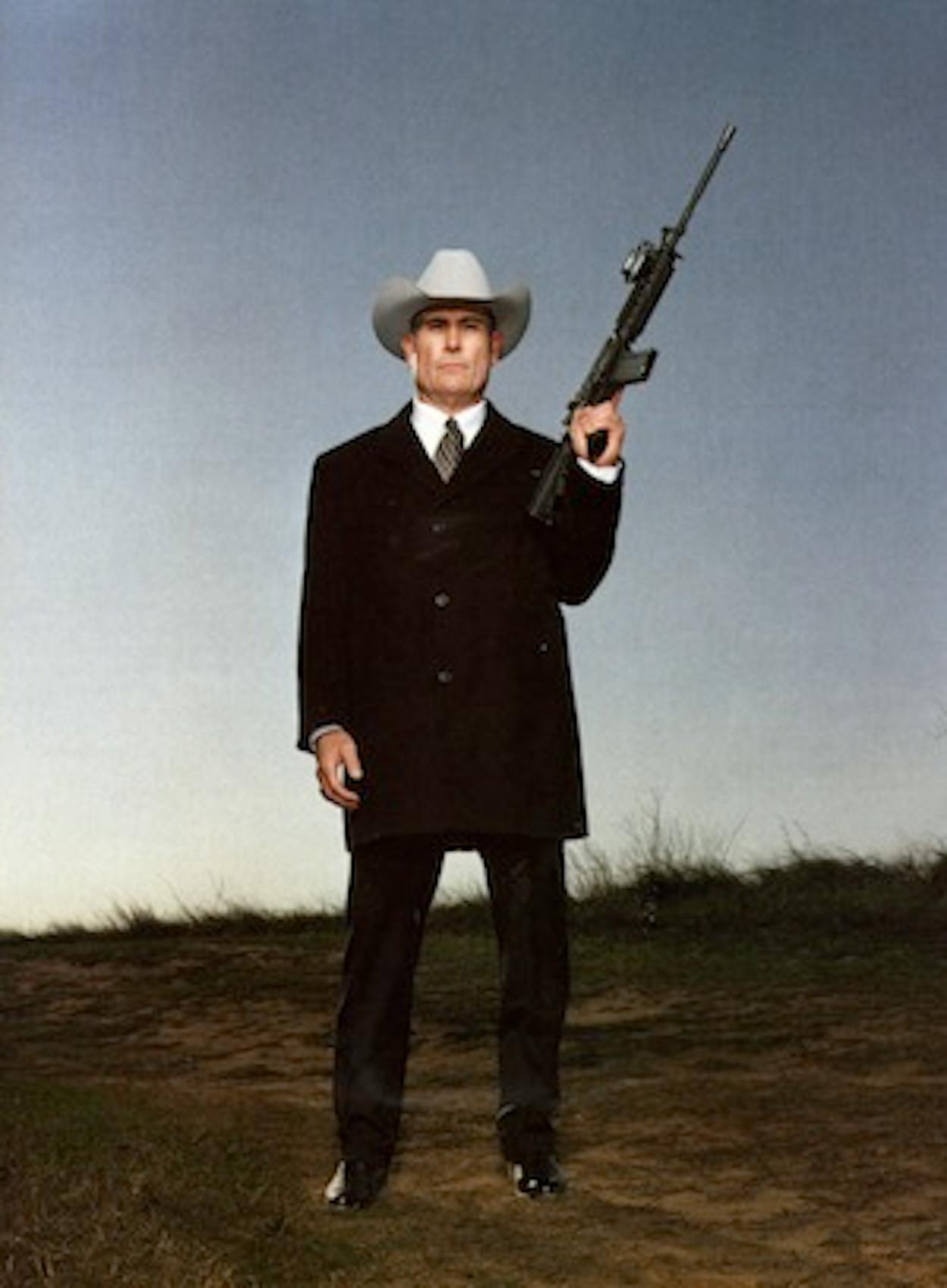

While the job has changed, the Rangers’ Western dress has stayed the same throughout most of the past century.

KENNY RAY: You know, in rural Texas, we don’t really stick out. It’s when I go to an urban area that I attract attention. You just don’t normally see a guy in Houston or Dallas walking down the street wearing a cowboy hat and a big old gun belt. The double rig that a lot of us wear goes back to the Old West. If you watch a John Wayne movie, he’s got a belt that holds his britches up, and he’s also got his gun belt. Well, we wear the same thing, just like Rangers before us did. Most of us get them made in the prison system. Now, we pay for them, of course; it’s not a perk or anything. But I’ve always thought that was kind of ironic that we send those guys to prison and then they have to build our stuff.

CAPTAIN BARRY CAVER became a Ranger in 1989. He heads Company E, in Midland: We don’t have an official uniform. It’s Western dress—a hat, boots, a solid-colored shirt, a tie, and a jacket, depending on the occasion. DPS gives us a clothing allowance of $100 a month, so a $500 hat and a $400 pair of boots cut into your yearly budget pretty quick. But the way we look is important. I learned early on in my Ranger career that when you approach a crook you’re about to interview and you’re dressed like a Ranger, he immediately sits up and takes notice and, in most cases, shows you respect.

MARRIE ALDRIDGE: As silly as this sounds, I think one reason we don’t have more females in the Rangers is because we wear Western clothes. Most females coming up through the ranks at DPS are from metropolitan areas, and they wouldn’t feel comfortable wearing a cowboy hat. Personally, I love it. I mean, I get to wear this and you’re going to pay me? That’s awesome. If I had been told, “Okay, you’re going to make Ranger, but you have to wear a dress and high heels every day,” I would have said, “No thanks.”

RAY MARTINEZ: Some Rangers in the early days did not have badges, so they would take a knife and cut a five-pointed star out of a cinco peso silver piece. The Ranger badge is still made from a cinco peso. The coin has to be from 1947 or 1948, because after that, their silver content dropped, so they tarnish. If you look on the back of any Ranger’s badge, you will see the Mexican eagle and the words “Estados Unidos Mexicanos.”

BROOKS LONG: It’s not an accident that our badges are made from cinco pesos, because we are attached at the hip to Mexico. That’s why the Rangers were put here originally—to secure the border. Our history, our legacy, our traditions are tied up in the border. That’s what has made us and given us our reputation, whether it be good or bad. That’s who we are, and that’s where we came from, and it’s important for us not to forget that.

KYLE DEAN: I don’t carry the weapon that DPS issues us, which is the SIG Sauer P226. Like a lot of other Rangers, I carry the Colt .45. It’s a luxury we’re afforded that the other services are not. We can carry the firearm that we think best fits our assignment. The way I see it, the Colt is a link to the past. That’s what the Rangers who came before us carried, and we’re continuing that tradition.

MATT CAWTHON: A lot of us carry the Colt Model 1911 semiautomatic, .45-caliber handgun. It has been around for nearly one hundred years, and it is tried-and-true. I was involved several years ago in a gunfight with a bank robber. While he was surrounded, he raised a pistol and tried to shoot at the highway patrol. We ended up having to shoot him, and he died in that gunfight. Forty-five caliber does a good job, I’ll tell you.

BROOKS LONG: I carry a SIG, and the reason I carry a SIG is that my life is not going to depend on tradition or history. My life is going to depend on my training, and I trained with a SIG.

FRANK MALINAK: You know, we look back now at the Rangers in the late 1800’s as having old-fashioned firearms, but then, the Colt was cutting-edge technology. In fact, the Walker Colt is named for a Ranger, Samuel Walker, who helped develop it. The Rangers saw a need for a reliable, well-designed, heavy-duty revolver that they could take out on remote patrols. The firearms that were available back then weren’t as fast or as easy to load, so the Colt was a pretty revolutionary firearm. Until then, you had to hand-load every round, and if you carried one revolving pistol, you only had six rounds. We are always looking for new technology to make us better, and the Rangers were doing the same thing back then.

BARRY CAVER: Something that hasn’t changed since the old days is that we still mount up on horseback, believe it or not. Whatever the situation calls for, that’s what we do.

DAVID HULLUM: About four times a year I get to go on a manhunt, and let me tell you, that is some extreme horseback riding. Most manhunts are at night, and you’re going through thick brush at a dead run, and you have to fight just to stay on your horse because your horse is following those dogs. Horses can go places that no vehicle can—not a four-wheel drive, not a four-wheeler, not a motorcycle, nothing. For one manhunt, we were on horseback for six and a half hours riding through some of the roughest terrain I had ever been on. I told the sheriff, “Heck, I don’t know about putting this guy in jail. You ought to send him to the dadgum Olympics trial!” We chased him hard, and he stayed just ahead of us for fifteen and a half miles until we caught him.

“IT WAS THE END OF AN ERA.”

Change hasn’t always come easy for the Rangers, whether it’s evolving technology or allowing women into their ranks.

LANE AKIN: When things started changing in the late eighties, some Rangers balked. I saw that happen when we first got computers. It led to retirements because the older guys just refused to change. They had handwritten their reports for as long as they could remember, and they weren’t about to start doing things any differently. I remember going to Bill Quinn’s retirement party, in ’87. Bill took the podium and said, “The captain’s been talking about putting a computer on my desk, so I think the time has come for me to go.”

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: When they started talking about giving us computers, you know, I was a street officer. I didn’t have any use for a computer. I didn’t think a Ranger should be tied down to an office. Anyway, they issued all of us laptops and sent us to a weeklong computer school so we would know what a cursor was and where the power button was. When I got back to Laredo, I used mine as a doorstop.

LANE AKIN: I remember one Ranger up in Childress, Leo Hickman. Leo had an eye shot out in a gunfight in East Texas. He was a World War II veteran and just a super guy—but he was crusty. Oh, my goodness, was he crusty. Well, we used to have mandatory retirement at the age of 65. Leo woke up on his sixty-fifth birthday and went to work. In Austin they were wringing their hands: “What are we going to do? Leo’s at work!” But they left him alone, and Leo worked until he was 72. Leo made up his mind that he’d been a Ranger long enough without a computer. He retired in 2001 and never used one.

KENNY RAY: The technology completely passed those guys by. I don’t want to say the older generation looks down on us, but they kind of kid us now: “You can’t do your job without a computer and a cell phone.”

JOAQUIN JACKSON: Computers came first. We all knew women were coming next.

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: What did some of the older Rangers do when women came in? They quit! I personally know one who retired over that issue. They were of the opinion that men were just meant to be Rangers, and they thought it was going to be very hard for a female to intimidate and get a confession from, you know, a member of the Mexican Mafia who had been in the penitentiary for 25 years and had killed three people.

JOAQUIN JACKSON: It was the end of an era. I think some of us felt that things were changing too damn much. And we were tired, too. A lot of us retired in ’93, and we were all in our late fifties and sixties. At 57, I wasn’t getting out the door as fast when I was being called out at two or three o’clock in the morning. It was time to hang it up.

MARRIE ALDRIDGE: I was the first female Ranger. I made Ranger in 1993. There was a lot of publicity and TV cameras there for a while, and I was glad when it died down. Because to me, I had just made Ranger like all these other guys. Everybody wanted to interview me, and I hadn’t even done anything yet. I have a scrapbook of news clips from back then, and there is a cartoon that says something like “Are the Texas Rangers going to have saddlebags made out of Tupperware now?”

DOYLE HOLDRIDGE: When this all took place, I was very, very negative about females joining the Rangers. But attitudes change, and as time went on, I accepted it. You know, I work for the sheriff’s office now, and I’ve got about eighty people working for me. Some of them are women, and they’re excellent officers. And I’ve gotten to work with Marrie, and I’ve got nothing but the highest regard for her. Marrie is a friend of mine now. But the first five years she was a Ranger, I didn’t speak to her. I thought, “If I ignore this, maybe this will go away,” and that’s what I did until I realized how big an ass I was being one time when she went out of her way to help me on a case. I feel bad about how I treated her back then.

MARRIE ALDRIDGE: I think everyone was a little leery of me at first. They were told, “Watch what you say, watch what you do. There’s a woman in the house now.” But I didn’t run into any problems. After I was around for a little bit and people got to know me, I said, “Look, nothing y’all are going to say is going to bother me. You know, if it does, I’m not in the right field.” I was raised with four brothers, so it’s pretty hard to shock me.

TONY LEAL: People are slow to change. In the past we did not have the recruiting that we should have had when it came to women. But our chief, Ray Coffman, has made it a priority to make sure that women know they are needed, welcomed, and wanted within the Rangers, and I’m doing everything I can personally to make that happen. It is our job, as captains, to recruit those qualified people. You know, there was a time when a Hispanic man or a black man couldn’t think about being a Ranger. Everything evolves. That’s not an issue anymore, and there will come a day when it’s not an issue anymore for women either.

BROOKS LONG: Times have changed, okay? And so somebody who was a great Ranger thirty years ago might not be a great Ranger today. I’ll never forget the lessons I learned from those older guys when I was a rookie. But we live in a different society now. Back then, heavy-handedness might have been used when you were trying to get a confession. Now you have to be a good listener. How you document the chain of evidence, how you protect the crime scene—everything has changed. Thirty years ago a Ranger could pick something up at the crime scene, tell the jury, “I found it,” and that was good enough at trial. Now you need to document who located it, who it was turned over to, who retained custody—those kinds of things are crucial. The job is less physical and more mental.

FRANK MALINAK: In years past, Rangers were famous for few words and even fewer reports. Nowadays we spend a lot of our time writing reports and documenting our investigations. Sometimes the most damaging evidence a defense attorney can face is a well-documented, comprehensive police report.

TRACY MURPHREE: I think the reason the Rangers have survived since 1823 is our ability to adapt. The Rangers went from single-shot pistols to the Colt, from the horse to the automobile, and now we’ve grabbed onto the computer age, DNA, and new crime-scene technologies. You know, you can move forward or you can stay still and die.

MATT CAWTHON: The Rangers were here before there was a Texas, and we have survived all that time. Now, we didn’t survive because we were good at riding horses. We didn’t survive because we can hunt or camp out on the prairie. We survived by being able to change with the times. When Texas needed Indian fighters, we were Indian fighters. When Texas needed border war fighters, we were that. When Texas needed someone to quell oil boom riots, we did that. When Texas needed detectives, we became that. When DNA became the mainstay of law enforcement work, we got good at that. We’ve had to change, and there have been some growing pains along the way. We have tripped and stumbled, and we’ve had times that were not our finest hours. But by and large we’ve had more successes than we’ve had misses. And we’re going to keep changing and evolving so we’re still here a hundred years from now.

- More About:

- Texas History